The class issue: examining economic and social inequality across Canada

Canada’s growing wealth inequality is a cause for great concern for the country. There are questions about whether this inequality is related to class – and, just as fundamentally, if class is a term that remains relevant today. To help answer these questions, Dr Michelle Maroto, Dr Zohreh BayatRizi and Dr Guillaume Durou, from the University of Alberta, are leading the Great Canadian Class Study, a large-scale project using surveys, interviews and other tools to understand the links between economic, social and cultural factors within Canada’s diverse population.

Talk like a sociologist

Class — the division of people based on perceived social and economic status

Demographics — statistical characteristics of human populations, such as age or gender

Gig economy — a labour market characterised by short-term contracts and freelance work, as opposed to permanent and stable employment

Income — money received regularly through work or investments

Shareholder — someone who holds shares of a company (portions of a company’s capital), entitling them to a proportion of the profits

Wealth — financial and physical assets (such as property), minus debt

Canada’s wealth gap – the difference in wealth between the country’s richest and poorest – is growing fast. “In 2025, the richest 20% of households held about 65% of Canada’s total wealth,” says Dr Michelle Maroto. “The same trend is true for income.” This is bad news at the national level, because it means a growing number of people are facing economic insecurity. “Many Canadians are only just getting by,” says Dr Guillaume Dorou. “Any adverse event, such as losing their job or facing a health issue, would leave them struggling to pay their monthly bills.”

It is very possible that these trends are interlinked with class, but class is very difficult to define these days, which is why Michelle, Guillaume and their colleague Dr Zohreh BayatRizi, all from the University of Alberta, decided to launch the Great Canadian Class Study (GCCS). The study aims to understand if class still matters, whether it is linked to income and wealth or other factors, and what it means for societal trends and the future of Canada.

Understanding class

Most commonly, class is thought of in terms of ‘economic capital’ – the income and wealth you have connected with your profession and ownership of property or other assets. “Some sociologists go beyond this definition to also include ‘social capital’ – your social network, which clubs and organisations you belong to, your family background, and so on,” says Zohreh. “They might also include ‘cultural capital’ , which includes your education level, lifestyle, accent, and tastes in music or art.” Taken together, these factors can define you in relation to other people and your place in society.

The concept of class is nothing new, but it was crystallised during the Industrial Revolution, which took place from the late 18th to early 20th centuries and saw rapid advancements in technology and mass industry. “A clear distinction arose between the people who worked in factories and the people who owned those factories – and between those people and farmers or small business owners,” explains Zohreh. “But today, the picture is more complicated.” Growing economic complexity, job diversity and complicated ownership models have complicated definitions of class. For example, concepts such as the gig economy and shareholding make the distinction between owners and workers less clear.

Moreover, the idea of defining people as belonging to the lower class, middle class or upper class is very much out of fashion and has connotations that many find unfair and prejudicial. The idea carries implicit assumptions that inequality is embedded into society and that people cannot (or should not) move between classes. Yet, whether or not we acknowledge it, it is still very possible that class continues to be a strong force within society. “We want to find out if class is now irrelevant – or, if it’s taken on a different definition,” says Michelle.

The Great Canadian Class Study

The GCCS is investigating definitions of class and aiming to understand what factors determine a person’s class, what people think about their position in society, and whether this influences how they vote or make other important decisions. Answering so many questions involves gathering a lot of different types of data. “First, we examined historical sources to see how ‘class’ has been used and defined in the past,” says Michelle. “Then, we sent an online survey to a representative sample of over 8,000 Canadians.” The questions in the survey covered general demographic factors such as occupation, income and education, as well as questions about whether respondents knew any people with certain other occupations, and what kinds of cars or houses they preferred to have. “We then followed up with about 200 people from the survey for a more in-depth online interview,” says Guillaume. “This enabled us to get responses that are often hard to get through a multiple-choice questionnaire.”

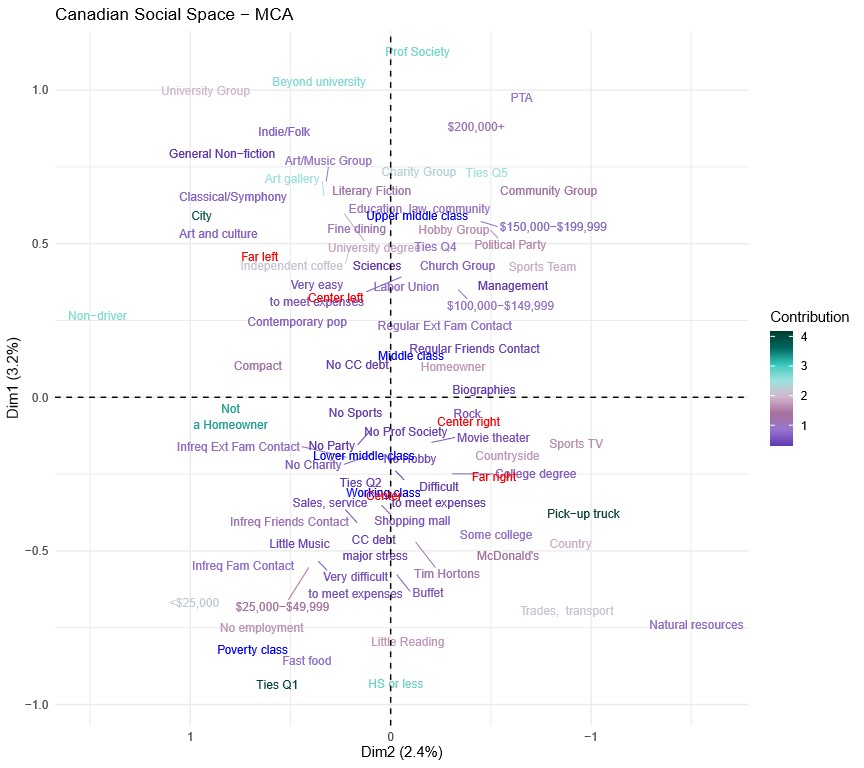

Once the data were collected, analysis commenced. “We looked at the relationships between measures for social, cultural and economic capital,” explains Zohreh. For instance, the team found that higher-educated people tended to prefer urban living, indie, folk or classical music, and visiting art galleries. Less-educated people tended to prefer rural living, watching sports on TV, and driving pick-up trucks. “There were links with income too,” says Michelle. “Members of higher-income groups have more social ties and are more involved in community and hobby groups. Members of lower-income groups, on the other hand, have limited social ties and less money to spend on extra activities.”

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM645

People with similar amounts of economic, cultural and social capital occupy adjacent spots in the social space. Here you see, for example, that in the bottom right quadrant people have low income, drink coffee from a coffee chain (Tim Hortons), are more likely to prefer pick up trucks over electric or compact vehicles, and are more likely to report supporting far right policies, while the top left quadrant is more likely to have people who prefer artisan coffee, visit art galleries, and support far left policies.

© Great Canadian Class Study

© Great Canadian Class Study

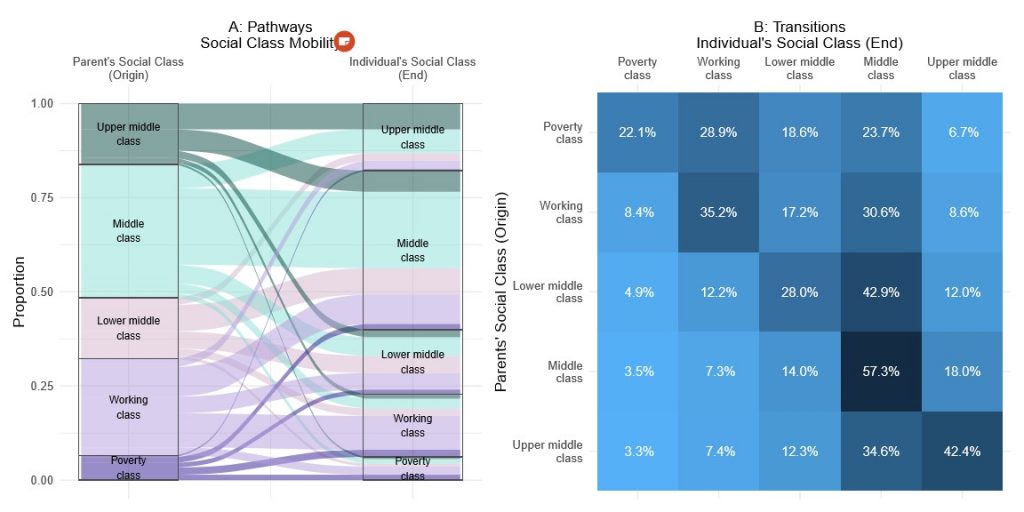

The team also wanted to understand how these trends might be changing through generations – if and to what extent people are following different paths to their parents. “There is a lot of intergenerational mobility for certain factors, especially among occupation,” says Guillaume. “Yet, factors like social class identity show very little intergenerational mobility.” This indicates that while people might get different types of, and potentially better paid, jobs than their parents, they mostly continue identifying with the social group within which they were raised.

What’s next?

The study’s results are still being processed – the big datasets mean that many further interesting relationships remain to be fully examined. “We still have a lot of data to analyse, and we will seek academic feedback on our work,” says Michelle. “Eventually, we plan to write a non-academic book based on our findings, which we hope will engage with a wide audience.”

In particular, the team’s research will uncover important information about how society is changing and is projected to change. “Recent years have seen a big rise in populist politicians and parties who specially appeal to ‘ordinary’ people,” says Zohreh. “Is this trend related to class issues? What is the relationship between inequality, social class identity and political affiliation?” Uncovering these relationships could help societies better support people across different economic and social classes, potentially helping to de-escalate political tensions and aid societal stability.

Dr Michelle Maroto

Dr Michelle Maroto

Dr Zohreh BayatRizi

Department of Sociology, University of Alberta, Canada

Dr Guillaume Durou

Department of Sociology, Faculté Saint-Jean, University of Alberta, Canada

Field of research: Sociology

Research project: The Great Canadian Class Study (GCCS): studying economic inequality and class in Canada through a large-scale, mixed-methods project

Funders: Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC grant #435- 2020-0451); Killam Foundation

About sociology

Sociology is the study of how society works, its development, structure and trends. It involves investigating cultural norms and practices, how and why we interact with each other in certain ways, and what drives social change. “Sociology is a wide-open field,” says Zohreh. “You can find something that interests you and channel your research in that direction.”

Sociology includes areas of study that endure over decades and new areas of study that arise to follow societal trends. “Enduring topics cover social questions around class and inequalities, health and crime,” says Guillaume. “Emerging topics cover social questions around technology, media, food, and so on.” In particular, an emerging field is ‘digital humanities’, which aims to understand how our social relationships and concepts are changing as they are increasingly influenced by technology. “New areas of study arise regularly,” says Zohreh. “Even if the area you want to study doesn’t exist yet, it can be created.”

Sociology has plenty of applications in the real world, too. Societal trends and values change over time and understanding why and how these changes occur is important for governance and policy. “Sociology can help people understand their own circumstances and help policymakers understand the consequences of their actions,” explains Michelle. “In this way, sociology can effectively contribute to positive change.”

Pathway from school to sociology

Subjects such as social studies, history, languages, literature and music all relate to our social relationship with the world, while a grounding in statistics and coding is useful for data analysis.

The University of Alberta, where the Great Canadian Class Study is based, has an annual fair, including a sociology table, open to high school students. The University also runs various programmes for high school students.

At university, courses or modules in sociology, social sciences, social psychology, anthropology, economics, law, history and politics can all lead to a career in sociology.

Explore careers in sociology

Many countries have a national sociology association, with a website that will offer information, resources and opportunities to gain experience. For instance, Canada has The Canadian Sociological Association.

Zohreh, Michelle and Guillaume recommend reading sociology journals and visiting libraries – including university libraries, which are often open to the public – to find introductory sociology books to learn more. Visit the online Sociology journal.

Meet Michelle

As a teenager, I felt the only two university options were law and medicine. I didn’t want to deal with blood or injuries, so I started on the track to be a lawyer, but it didn’t captivate me. Then, I took an Introduction to Sociology course. I was hooked, changed my major to sociology, and the rest is history.

I’ve had so many mentors and supporters along the way. For instance, I worked as an undergraduate research assistant for a professor who encouraged me to go to graduate school. People like that professor have helped shape who I am and what I do.

Research is about sharing knowledge and engaging in conversation about it. And not just among academics – among all of society. If we want our work to matter and create social change, it needs to be accessible to a range of different audiences.

When I’m stuck on a problem, I go for a run. For me, running outdoors is the perfect way to ponder a challenge and overcome it.

My achievements have been mostly ‘steps’ rather than big moments. Each conference presentation, paper and article is an achievement. Each student who I can help with a topic they are struggling with is an achievement.

There are always so many projects that I want to work on. Right now, I’m working with a team to develop the Transforming Research for Social Impact Hub, which will promote community-engaged and socially-responsive research.

Michelle’s top tip

Ask questions, and learn how different research methods can lead to the answers.

Meet Zohreh

During my childhood, Iran’s political circumstances greatly influenced my way of thinking. The fallout of the Islamic Revolution brought about civil unrest and very strict rules for citizens. As a teenager, I grew sceptical of the imposed ideology. Sociology attracted me as it offered many different lenses for viewing society, in particular, how power operates and the assumptions we work under.

My research also looks at death and dying. While death is biological, the way we relate to it is influenced by our social and cultural circumstances. I asked people from different neighbourhoods in Tehran, Iran, about their attitudes towards death. Some higher-income people put death completely out of mind, but in the slums, people dealt with death daily, and visiting the graves of loved ones comforted them.

My PhD research into perspectives on mortality is my proudest career achievement. It even led to the publication of a book. A PhD is a rare opportunity to focus exclusively on one project and see where it takes you. The process of discovery was really fascinating.

You have to keep digging to overcome challenges. Sometimes, you can take a step back and then return with a fresh perspective. Having a hobby – sports, art, anything – helps refresh the brain.

I used to be terrible at switching off from work. Having kids changed that; now, I shut down the computer in the evenings and weekends to spend time with them and on my own hobbies.

After finishing the GCCS project, I want to find another that interests me. Long term, I aim to retire while I am still able to transfer some of my knowledge and experience to my home country of Iran.

Zohreh’s top tips

1. Find your own strengths and talents. People are great at different things.

2. Once you find your strength, work hard at developing it. As time goes on, it will become easier.

Meet Guillaume

My curiosity for better understanding social relations and social problems led me to sociology. I was trained as a political scientist, but I switched to sociology because that’s where I found answers to my questions. I’d also met inspiring sociology professors, and I wanted to be like them.

I work at Faculté Saint-Jean, of the University of Alberta, which is a unique environment. Everything is in French, from the classes to the administration, and the students speak French. This means it is possible to learn in French in a post-secondary institution and do research in French.

Music is a big part of my life! I’ve been playing guitar for years, in bands and for myself. That’s the best way to switch off from work.

My proudest career achievements so far are being able to do my own research, in French, in Alberta, and becoming an associate professor in sociology.

In the future, I want to bridge my research with the linguistic minority communities in Western Canada, so they can have access to social science and better understand their history and their future.

Guillaume’s top tips

1. Never give up.

2. Listen to those around you but trust yourself.

3. The world is full of opportunities. Sociology is one of the awesome ones!

Do you have a question for Michelle, Zohreh and Guillaume?

Write it in the comments box below and they will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

0 Comments