The history of science and culture through the medieval lens of alchemy

Alchemists believed that, if their mind, body and spirit were pure, they could create the Philosophers’ Stone – a substance that could heal people from illness and turn base metals into gold. At McGill University in Canada, Dr Matteo Soranzo is analysing medieval manuscripts written by the 15th century alchemist Cristoforo da Parigi. Matteo’s work is highlighting how culture shaped, and continues to shape, scientific ideas and priorities.

Talk like an Italian studies researcher

Alchemist — someone who practises alchemy

Alchemy — the medieval discipline concerned with creating the Philosophers’ Stone, which combined philosophy, early understanding of chemistry and ideas about magic

Base metal — a non-precious metal, such as copper, tin or lead

Medieval — the period in European history from the 5th to 15th centuries

Philosophers’ Stone — a mythical substance capable of curing illness and turning base metals into gold

Textual criticism — the academic process of determining the most accurate version of an original text by comparing all available existing versions

Transmission — how a text has evolved over time as it has been copied

Transmutation — the process of transforming one substance into another, such as base metals into gold

Cristoforo da Parigi was a mysterious man – an alchemist passionate about using knowledge to help the poor and to address social and economic injustices. “The identity of Cristoforo is still shrouded in mystery,” says Dr Matteo Soranzo, a professor of Italian studies at McGill University. “My research suggests that he might have been a pharmacist, writing letters from Paris in the 1400s to a man named Andrea Ognibene back in Cristoforo’s hometown of Venice.”

What were alchemists trying to achieve?

The medieval discipline of alchemy focused on two key aims. “First, there were practical concerns of making the Philosophers’ Stone – a substance believed to be capable of turning base metals into gold, as well as healing humans from various ailments,” says Matteo. “There was also an emphasis on reaching the spiritual and mental mindset necessary for the alchemist to succeed in this very difficult operation.”

Alchemists believed that purity of both body and soul were needed to successfully create the Philosophers’ Stone. While Matteo has not yet identified Cristoforo in historical records, he is learning about him, his peers and the culture in which they lived through the letters Cristoforo wrote. For example, Matteo has discovered that Andrea (the recipient of Cristoforo’s letters) belonged to a religious order that encouraged its members to whip themselves to seek forgiveness for sins. “Elements of this harsh spirituality appear in Cristoforo’s letters as necessary steps to achieve the alchemical transmutation,” explains Matteo.

How is Matteo analysing Cristoforo’s texts?

First, Matteo must find copies of Cristoforo’s works. “I travel to libraries and archives throughout Europe and North America,” he says. “It is remarkable how many 15th century manuscripts crafted in Italy ended up in other countries.” Then, he transcribes and translates the manuscripts and uses digital tools to help him annotate the sources so he can compare different copies of the same text.

Matteo is interested in the transmission of Cristoforo’s texts – how his original letters were reproduced and shared. “Manuscripts appear to have been copied by amateur scribes, driven by interest in Cristoforo’s alchemical knowledge,” he says. Analysing ancient manuscript sources in this way is called textual criticism, a cutting-edge historical method for recreating old texts. “This involves reconstructing the transmission of a text and establishing a critical edition (an accurate version of the original text) by comparing all the existing copies available and formulating a hypothesis about their mutual relationships,” explains Matteo.

Matteo has two main aims for his work. “At a basic level, I want to bring back to life a very prolific, yet largely forgotten, writer and sharer of alchemical ideas who used the everyday Italian of the time, rather than Latin, as his language of choice,” he says. “At a more ambitious level, I want to build a bridge between textual criticism and the history of science, showing how these disciplines can benefit from each other.” Matteo’s work enables him to explore the cultural history of late medieval Italy, and to make contributions to our understanding of the history of science. “My research explores how scientific knowledge and ideas were embedded in and influenced by broader culture,” he explains. “My work examines how scientific concepts were communicated and understood by the public.”

What stories does Cristoforo tell?

By translating Cristoforo’s letters, Matteo has uncovered fascinating details about how beliefs in alchemy were embedded in everyday medieval life. For example, Cristoforo tells Andrea about finding an urn in an ancient Roman tomb which he said was filled with quintessence – the pure ‘fifth element’ that was believed to fill the heavens. “According to Cristoforo, thanks to this remarkable substance the urn was still emanating a pleasant scent centuries after its construction,” says Matteo.

One letter tells of a glassmaker on the island of Murano in Venice who was creating the glass tools that alchemists used to try and create the Philosophers’ Stone. Today, Murano is famous for producing beautiful hand-blown glass, but Cristoforo’s writing shows that in medieval times, its artisans were investing their glassmaking skills in alchemical pursuits.

“Finally, there is Cristoforo’s emphasis on the alchemist’s spirituality, necessary to achieve the much-sought-after transmutation of base metals into gold,” says Matteo. “His letters include detailed instructions on how to achieve this state of spiritual perfection.”

How does culture impact scientific ideas?

Perhaps most importantly, Matteo has learnt how Cristoforo’s motives were influenced by the culture of the time. “Building on medieval ideas, Cristoforo wanted to use alchemy to correct socio-economic injustices,” says Matteo. “He addresses his teachings to Andrea, a man who is struggling to feed his children. Cristoforo wishes the Philosophers’ Stone is used only by poor people who are well-intentioned and spiritually sound. At the time, a capitalist economy was becoming the norm in Italy and Europe, and it looks like Cristoforo wanted to correct the excesses of this new economic system and its impact on society.”

Matteo’s work helps us to explore how scientists are influenced by the culture of their time. “Some scientists today isolate their pursuits and discoveries from their culture,” says Matteo. “However, research questions and methods do not come about in a vacuum but are shaped by the surrounding culture. An emphasis on technology and financial profit reflects a Western capitalist culture and practices like ‘extractivism’ – exploiting resources for economic gain. These focuses often marginalise alternative approaches driven by ancient beliefs that nature is a living being that needs to be protected. Looking at the past helps us look at the present as a possible answer, but not the only answer, to questions that are as old as humankind.”

Dr Matteo Soranzo

Dr Matteo Soranzo

Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures, McGill University, Canada

Fields of research: Italian studies, literature studies, cultural history

Research project: Analysing texts written by the medieval alchemist Cristoforo da Parigi

Funder: Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC)

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM650

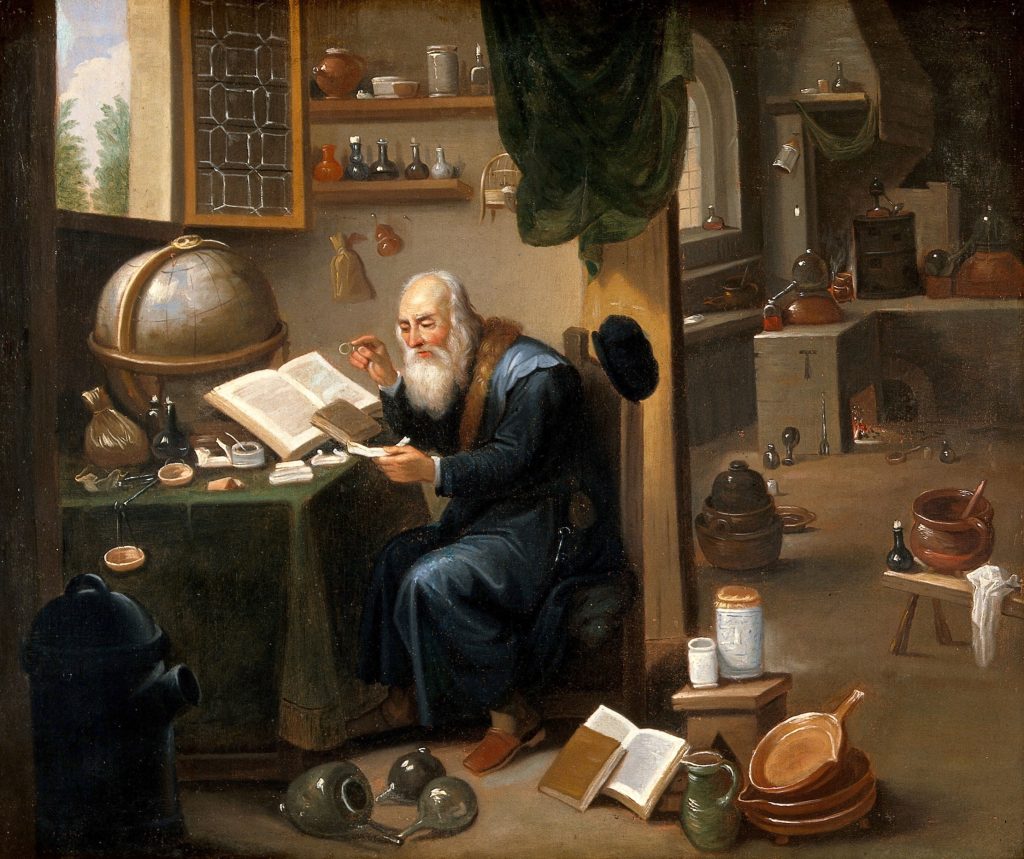

Medieval alchemists tried to create the Philosophers’ Stone, a mythical substance capable of curing illness and turning base metals into gold.

© Rawpixel.com/Shutterstock.com

Drawings of alchemical tools from a copy of Cristoforo da Parigi’s Lucidario dell’Arte Trasmutatoria.

© McGill University, MS Osler 7529 fol. 94r (Internet Archive)

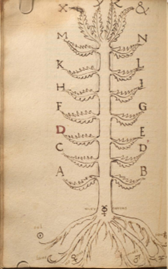

A tree diagram from Cristoforo da Parigi’s Lucidario dell’Arte Trasmutatoria. This diagram is inspired by the philosopher Ramon Llull, in which each letter corresponds to chemical substances and operations.

© McGill University, MS Osler 7529 fol. 47v (Internet Archive)

Locating, transcribing, translating and collating ancient texts is challenging work, but intellectually rewarding.

© Gorodenkoff/Shutterstock.com

About Italian studies

The field of Italian studies covers everything from ancient Roman history to modern-day Italian fashion. It is the exploration of Italy’s language, art, literature, history and culture, and how it maintains a distinct identity while taking inspiration from and inspiring the rest of the world.

Matteo focuses on Italian literature studies and cultural history. “I have always been interested in how literature reflects ideas from philosophy, astrology and alchemy,” he says. “Literary texts are often seen as ‘just fiction’ but, on closer inspection, they build on knowledge structures that their authors and readers considered facts. Looking at a text as weaving together multiple ways of thinking allows me to grapple with historical worldviews often very different from our own.”

The importance of language skills

Having a deep understanding of the Italian language, including how it developed from Latin and regional variations, is essential, challenging and incredibly rewarding. “Somebody who wants to investigate pre-modern Italian culture should learn Italian, but with an open mind,” says Matteo. “Late medieval and Renaissance (14th to 17th century) Italian is quite different from that used in Italy today.” Similarly, having a good understanding of Latin and Greek is important, but equally full of surprises; the Latin used by medieval writers can seem rather strange and confusing for students and scholars more familiar with standard classical languages. “If I could go back in time, I would also study Arabic,” says Matteo. “Medieval culture was shaped by Greek texts that arrived in Europe in Arabic translations, which were eventually translated into Latin.”

Pathway from school to Italian studies

Learn Italian! In addition to taking language classes, surround yourself with music, movies, podcasts, artworks and books – they are so easy to access online today. “Learning a new language is a time-consuming but very rewarding pursuit,” says Matteo. “Language competence is also a highly perishable skill, which needs to be constantly trained.”

If your school does not offer Italian lessons, then other modern and classical languages will still help develop your language skills. It would also be useful to study literature and history.

At university, study Italian or Italian studies, which will introduce you to the country’s language, culture and history. These programmes will include the opportunity to study in Italy so you can immerse yourself in the language and culture. Depending on your interests, you could also earn a degree in literature, history or art history and tailor your studies to focus on Italian examples.

Explore careers in Italian studies

As an Italian studies researcher, you could have an academic career studying whichever aspect of Italian language, literature, culture, history or art most interests you!

Learn more about the research being carried out by Matteo and his colleagues in the Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures at McGill University: mcgill.ca/langlitcultures

Organisations such as the Society for Italian Studies (italianstudies.org.uk), the American Association for Italian Studies (aais.italianstudies.net) and the Association for the Study of Modern Italy (asmi.org.uk) provide information about the latest Italian studies research and organise events and conferences which you could attend as a student member.

“Like Italian scholars of the 1400s used to encourage their pupils, I would advise young people to go ad fontes, or ‘to the sources’,” says Matteo. “Immerse yourself in actual things from the past and let them speak to you.” Visit museums or explore their digital collections. For example, the Vatican Museum (museivaticani.va) has a wealth of Italian historical artefacts you can examine online.

Meet Matteo

I’ve always loved learning languages and travelling. Growing up in Europe, it was much easier to experience cultural differences without spending hours on an airplane, so I consider myself lucky on that front. As a teenager, I also liked hiking and biking in the mountains as a slow-paced way to experience the landscape that felt very much like learning.

I decided to dedicate my studies to culture and literature after reading S.T. Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798). I know mine is not a standard interpretation of this poem, but when I read it, it felt like it gave shape to the thrills, fears, depressive states and sudden moments of euphoria that characterise – at least for me – the intellectual journey. So, I embarked on my studies as if I was going a lifelong journey that keeps sailing on, so to speak.

I was motivated to study discarded forms of knowledge, such as alchemy and astrology, due to my frustration with literary studies and their tendency to interpret anything in literary texts as ‘fiction’. However, to make sense, a poem or a novel must build on a knowledge structure that authors and readers accept as factually true. If a medieval poem states that the planet Saturn is the cause of a character’s melancholic state or that a devil takes on a solid body and physically harms people, this is not fiction. In medieval times, knowledge from astrology and demonology explained these phenomena as facts. But modern ideas have stigmatised these beliefs and made these forms of knowledge obsolete. Reading outside of the ‘literary’ canon offers modern readers a point of entry into a different mentality.

For my research, I work with texts that are not available in modern editions, so first I must transcribe and collate all the manuscripts I find. These tasks are challenging because they are demanding and time-consuming, but they lead to intellectually stimulating research.

In my free time, I like travelling with my family, running, working out and gardening.

Matteo’s top tip

Try to ask yourself why certain things interest you while others do not. External pressure and expectation are only going to take you so far, so be true to what genuinely interests and inspires you.

Do you have a question for Matteo?

Write it in the comments box below and they will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

Discover how an Italian printer and publisher influenced the books we read today:

futurumcareers.com/how-did-a-renaissance-printer-shape-the-books-we-read-today

0 Comments