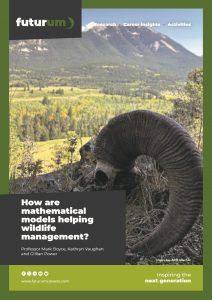

How are mathematical models helping wildlife management?

Humans deliberately manage wildlife populations for a variety of reasons, such as sustainable harvesting or to prevent overpopulation, the spread of disease or risks to domestic animals. But sometimes, management measures can have unexpected results. This is why conservation must be based on scientific evidence. At the University of Alberta in Canada, Professor Mark Boyce and his students, including Kathryn Vaughan and Gillian Power, are modelling wildlife populations to help inform management decisions.

Talk like a conservation ecologist

Game species — animals hunted by humans

Mortality — the number of deaths in a population

Snow water equivalent — the amount of water produced when a given volume of snow is melted (i.e., a measure of the density of the volume of snow)

Statistical modelling — applying statistical analyses to a dataset to find patterns and relationships among variables

Sustainable harvesting — hunting animals to manage their population

Winter severity index — a metric to quantify the harshness of a winter season

From grizzly bears roaming the Rocky Mountains to herds of bison grazing the Prairies, Canada is home to an incredible diversity of wildlife. But despite their ‘wild’ nature, many of these species are closely managed by humans. “Game species (e.g., deer, elk, moose) are managed for hunters,” explains Professor Mark Boyce, a conservation ecologist at the University of Alberta. “Other species are managed to reduce risks to livestock (e.g., wolves) or crops (e.g., boar), or for their own protection (e.g., grizzly bears in Alberta).”

However, knowing the best method for managing wildlife is not straightforward. “Often, wildlife management decisions are made with insufficient evidence because it’s expensive to accurately monitor populations,” says Mark. “Or political interference can mean decisions are based on public opinion rather than advice from scientists.” For example, people in urban areas generally favour wolf protection, while people in wolf-inhabited areas generally favour wolf hunting to protect their livestock and pets.

Population management: follow the science

Wildlife populations change size according to their rates of reproduction and mortality, which are influenced by numerous factors such as availability of food, predator and prey interactions, weather conditions, disease and hunting. Complex mathematical equations can incorporate these variables into models that predict how populations will change over time. In the Boyce Lab, Mark and his team develop such models to investigate how wildlife populations will respond to different management strategies.

There are many forms of wildlife management, including direct management (killing or protecting animals), or indirect management (managing habitats, e.g., planting native species or removing vegetation through controlled burning). But before making management decisions, it is important to have a robust understanding of their likely effects. History is littered with stories of when wildlife management went wrong. A famous example is the introduction of cane toads to Australia – they were introduced to control crop pests but soon became invasive and had catastrophic effects on native species. Wildlife management strategies can have unanticipated outcomes, which is why Mark is a strong advocate for science-based management built on real-world data and mathematical models.

Surprising population changes

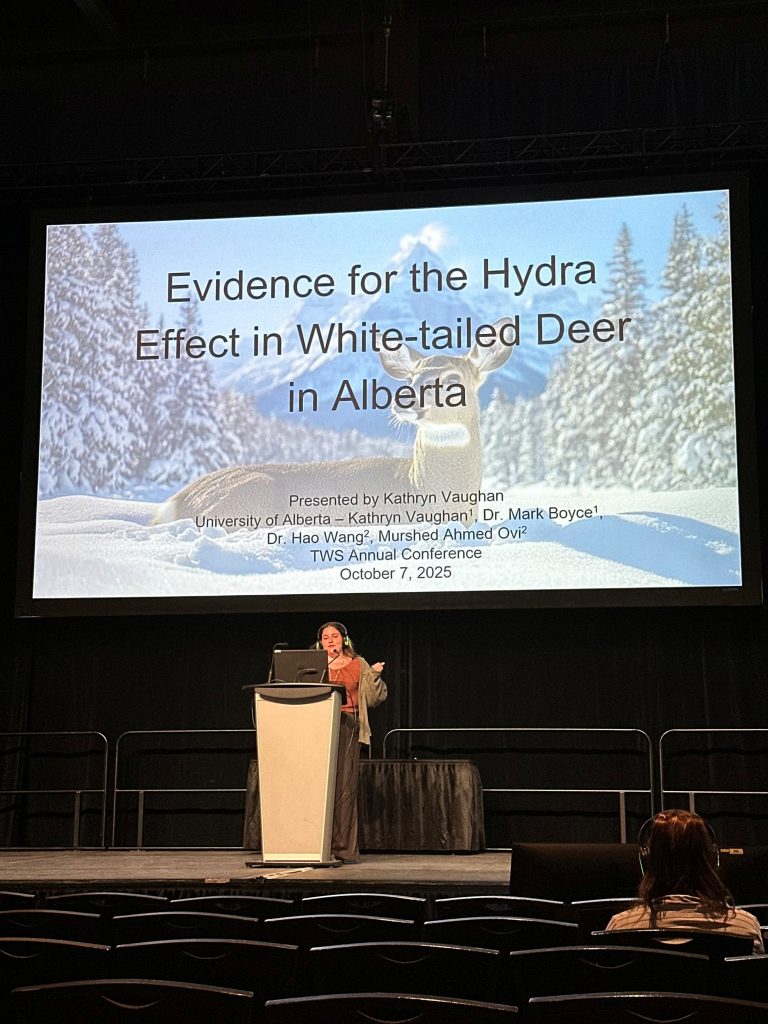

Population ecology models have revealed counterintuitive phenomena which mathematically explain why some management strategies fail. The Hydra Effect is named after the many-headed monster in Greek mythology – each time a head was cut off, two more grew in its place. “For certain populations, we find that low to moderate levels of hunting can actually result in increased abundance of the species,” says Mark.

The Hydra Effect occurs because surviving individuals have less competition for resources, leading to a ‘baby boom’ and increased population. This has significant implications for wildlife management. “For game species, the increased abundance caused by low to moderate hunting is good news for hunters,” says Mark. “On the other hand, for species in conflict with humans, hunting can be counterproductive.” For example, hunting wild boar in an attempt to stop them damaging crops actually leads to increased boar populations and greater crop damage.

Another counterintuitive effect is the Volterra Principle. “When both predator and prey species have an increase in mortality, the prey species then increases while the predator species decreases,” explains Mark. “This has implications for how we manage predator and prey populations as it calls into question the use of predator control to manage game species.” For instance, a wildlife manager may want to kill wolves to increase the deer population for hunters, but according to the Volterra Principle, both predator and prey should be targeted.

Winter is coming

Canada is a country of seasonal extremes, where winters can be very harsh. This has a significant impact on white-tailed deer populations, a species that provides over $35 million to the Albertan economy through the hunting industry. Kathryn Vaughan, a master’s student in the Boyce Lab, developed a winter severity index to help manage deer populations. “A winter severity index is a tool to measure the harshness of a winter season, based on factors like temperature and snow conditions,” she explains. “Colder weather means deer use more energy to stay warm, and deeper snow makes it harder for them to move around to find food and shelter.”

Wildlife managers need to understand the effects of winter on deer populations to decide how to manage them, but traditional winter severity indices are overly simplified. “To make a more accurate and flexible index, I used 20 years’ worth of satellite data of temperature and snow water equivalent,” says Kathryn. “Snow water equivalent is a measure of how dense the snow is, which gives us a better understanding of the amount of energy deer use to move through it.”

Kathryn used her new winter severity index to explore whether sustainable harvesting could help with white-tailed deer management to prevent population crashes after severe winters. “Interestingly, I found that areas with more hunting tended to have more stable and even slightly higher average abundance,” says Kathryn. “This suggests that consistent hunting may help prevent overpopulation, by decreasing competition for food and shelter when they are limited during tough winters.”

Preventing sheep disease

Preventing the spread of diseases between domestic and wild animal populations is a key part of wildlife management. Gillian Power, a PhD student in the Boyce Lab, is exploring disease transmission to wild bighorn sheep, a species famous for dramatic head-butting dominance displays. “Domestic sheep and goats carry a bacterium that can cause pneumonia in bighorn sheep,” Gillian explains. If wild bighorn sheep come into contact with domestic animals, pneumonia outbreaks can devastate their populations, which take generations to recover.

It is essential to understand how these outbreaks occur to effectively manage and protect wild populations. “We are placing radio collars on bighorn sheep, which allow us to track and analyse their movements,” explains Gillian. “I will use statistical modelling and machine learning simulations to understand the patterns within their movements.” She will supplement these data with real-life observations, spending time in the field to document the behaviours and interactions of wild bighorn sheep.

Gillian hopes to identify priority locations for surveillance, so wildlife managers can prevent contact between wild bighorn sheep and domestic animals. “Due to the severity of this disease, our best chance for maintaining healthy bighorn sheep populations is by preventing it from entering wild populations in the first place,” says Gillian. “I hope this project brings together people with passions for wildlife and domestic animals – by working together, we can make a bigger impact.”

As Mark, Kathryn and Gillian’s work highlights, conservation ecologists are essential for providing the scientific evidence required for making effective wildlife management decisions.

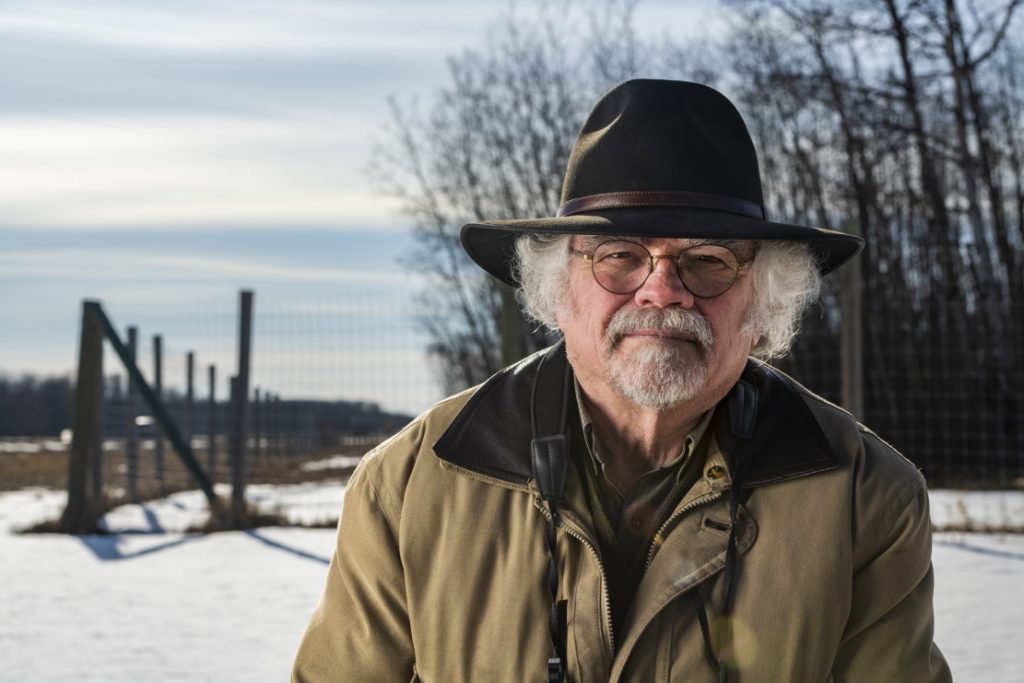

Professor Mark Boyce

Professor Mark Boyce

Boyce Lab, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Canada

Website: grad.biology.ualberta.ca/boyce

Research project: Modelling wildlife population dynamics to inform management strategies

Kathryn Vaughan

Master’s student (now graduated)

Research project: Developing a winter severity index to help manage white-tailed deer populations

Gillian Power

PhD student

Research project: Tracking bighorn sheep movement to prevent the spread of disease from livestock to bighorn sheep

Fields of research: Conservation ecology; wildlife management

Funders: Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSREC); Alberta Conservation Association (ACA)

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM660

During fieldwork, Gillian and the team capture wild bighorn sheep and use nasal swabs to test whether they have the bacterium that can cause pneumonia.

© Mike Smith

Members of the Boyce Lab have found that populations of elk are thriving in Alberta, despite an increase in predator species such as wolves, grizzly bears and cougars. © Mark Boyce

Members of the Boyce Lab have studied how black bear populations vary depending on land use, which has implications for management and conservation strategies. © Allan Colton

© Gillian Power

Pathway from school to conservation ecology and wildlife management

At school, get a good grounding in biology to learn about animals, ecology and populations, and mathematics and statistics to develop quantitative skills that are important for analysing data. “I also recommend learning coding and data analysis early on,” advises Kathryn. Look for courses to learn R, Python and GIS.

At university, a degree in biology, ecology or conservation would provide a direct route into the field, but other pathways also exist. Kathryn studied a degree in general biology, where modules in population ecology and animal behaviour convinced her to pursue a career in ecology. Gillian studied agriculture, livestock epidemiology and veterinary science before joining the Boyce Lab.

Mark notes that certain professional certifications, such as Certified Wildlife Biologist (e.g., wildlife.org/certification-programs) or Certified Ecologist (e.g., esa.org/certification), are often desired or required by employers. Pay attention to certification requirements in your region to ensure your qualifications will be recognised.

“There are many paths into conservation, and it can feel overwhelming at first, but remember that there’s a place for everyone,” says Kathryn. “Reach out and talk to people – you can learn so much from hearing different people’s career stories.”

Explore careers in conservation ecology and wildlife management

If you love the idea of working with animals, then conservation ecology and wildlife management could be the career for you. “Going into the mountains to watch sheep is a big perk,” says Gillian. “How often can you go hiking and camping as part of your job?”

“Most of my students get jobs working for government agencies, which hire wildlife biologists with strong quantitative skills,” says Mark. “There are also jobs in industry or consulting which involve mitigating the consequences of industrial development on wildlife. And some of my students stay in academic research.”

“With so many species and ecosystems to study, there are endless opportunities to make a difference!” says Kathryn. “No matter what animals or habitats interest you, there’s likely someone studying them, and you could be part of that work.”

Kathryn and Gillian recommend getting involved in local clubs or organisations to meet like-minded people, find volunteer opportunities and assess whether the field is right for you. For example, The Wildlife Society (wildlife.org) has local-level groups across North America and advertises jobs, internships and graduate research opportunities.

Meet Mark

In high school, I was an avid hunter and angler, which motivated me to study conservation. During a summer field course in my third year of undergraduate studies, I saw the lifestyle associated with a career in outdoor research. This motivated me to gear my life towards wildlife ecology research.

I love working with students – seeing them grow and go on to be successful professionals makes me very proud. And I love working with wildlife – every species that I’ve studied has been uniquely rewarding.

It’s motivating to see our research influence conservation and management decisions. I believe that science informs the best decisions, so it’s discouraging when politics and economics interfere. I sincerely hope that science will prevail in policy and government.

There is no better life than working in wild places with wildlife! This is a fantasy for many young people, and you can have these opportunities if you pursue this path with dedication.

Meet Kathryn

It was the TV show Zoboomafoo that first interested me in ecology. It sparked my love for animals and inspired me to want to help them. As I got older, I wanted to do that for others – spark curiosity, compassion and excitement for wildlife. Because as important as research is, we also need advocacy and education.

Progress in science doesn’t always mean everything goes according to plan; moments of confusion or failure have taught me the most. Wildlife research is highly collaborative, and working with experts in wildlife biology, mathematics and policy has taught me the importance of effective communication.

There are many moments I’m proud of throughout this research, but one of my proudest moments was finishing and presenting my master’s thesis. After I presented my winter severity index at a wildlife conservation conference, someone told me it was exactly what they needed. That moment made me realise my work truly had real value and that I had contributed something useful to wildlife management.

Humans have caused a lot of harm to wildlife and the environment, but we also have the power to make a positive difference. I want future generations to have the same wildlife experiences that I cherished growing up, like watching monarch butterflies outside my window and bird watching in the park. I hope to inspire others to pursue a career in conservation to make that happen.

Meet Gillian

My interest in wildlife was also piqued by watching Zoboomafoo! Growing up in a big city, I thought my only job options were zookeeper or veterinarian. Then, during my studies in agriculture, I learnt about other career options.

I am a strong proponent of the One Health approach. It focuses on the interconnected nature of health between the environment, humans and animals. Conservation is key to human and animal health, and we need to find ways to support wildlife and domestic animals.

I have just joined the Boyce Lab, and I’m looking forward to doing fieldwork with bighorn sheep. After my PhD, I hope to continue researching interactions between wildlife and livestock because humans and domestic animals keep encroaching on wild areas.

My favourite fact about bighorn sheep is that males experience such great forces when they head-butt each other that scientists are designing human concussion mitigation strategies by looking at the composition and structure of their skulls!

Do you have a question for Mark, Kathryn or Gillian?

Write it in the comments box below and they will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

Discover how statistical ecologists use mathematical models to study ecosystems:

futurumcareers.com/how-can-statistical-models-answer-ecologys-big-questions

0 Comments