Could the brain’s over-eager ‘pruning shears’ be causing schizophrenia?

Schizophrenia is still a very poorly understood psychiatric disease. Uncovering the factors that lead to schizophrenia is no easy task – but neurobiologists are on the case. At the Broad Institute in the US, Dr Matthew Johnson, Dr Beth Stevens and their team are investigating whether schizophrenia occurs when brain development goes wrong, causing too many connections between neurons to be destroyed. Their findings could help the development of treatments to prevent and manage this serious disease.

Talk like a neurobiologist

C4A — a protein that tags synapses to be engulfed

Microglia — immune cells in the brain responsible for synaptic pruning

Schizophrenia — a severe, chronic brain disorder that affects cognition, emotions and behaviour

Synapse — the connection between neurons that allows information to be transmitted through the brain

Synaptic pruning — the process by which microglia engulf unnecessary synapses

Schizophrenia is a serious mental illness, affecting about 1 in 300 people, or 23 million people around the world. “Symptoms include hallucinations and delusions, social withdrawal, difficulty with language and other cognitive impairments,” says Dr Matthew Johnson, a neurobiologist at the Broad Institute. His colleague, Dr Beth Stevens, continues, “Schizophrenia tends to develop during adolescence, and we still don’t fully understand why.”

Synaptic pruning

Matthew and Beth’s team is focusing on synaptic pruning and its relationship with schizophrenia. “Synapses are the connections between neurons that allow these cells to transmit information,” says Matthew. “This is how we learn, form memories and control our actions.” While we are developing during childhood, the brain makes excess synapses, to enable as much learning as possible. Later, once it is clearer which synapses are useful and which are less so, the body tidies up. During adolescence, unnecessary synapses are removed via synaptic pruning. These synapses get tagged by special molecules, which instruct immune cells called microglia to ‘eat’ them. “We are testing the hypothesis that too much synaptic pruning by microglia during adolescence is one (of many) causes of schizophrenia,” says Beth.

The team is studying the molecules that tag synapses to instruct the microglia to destroy them. “The C4A protein is one of these molecular signals,” explains Matthew. “Genetic studies have revealed that people with more C4A in their brain have a higher risk for schizophrenia.” The team used mouse models to test the link between C4A and schizophrenia. “We studied genetically modified mice that express human C4A,” says Beth. “Our findings show that these mice do indeed have increased synaptic pruning and show changes in social behaviour.”

Teen troubles

Given that schizophrenia typically emerges during adolescence, it is likely that the disease is linked to developmental processes that happen during this time. “Synaptic pruning is especially active during critical development periods such as adolescence,” says Matthew. To build on previous experiments, the team genetically modified new mice where extra C4A was only ‘turned on’ during adulthood, rather than being present from birth. “Our hypothesis is that mice with extra C4A-induced pruning during adolescence will perform worse at complex decision-making tasks compared to those where extra C4A expression is only during adulthood,” explains Beth.

The team is also assessing how environmental factors might contribute to the risk of schizophrenia. “Stress induces immune system responses, so could potentially exacerbate synaptic pruning by microglia,” says Matthew. “For example, stress might cause microglia to be more responsive to C4A tags.” The team is testing this by observing how mice respond to chronic stress and if that affects the rate of synaptic pruning and their behaviour.

Mouse brains

So, how does the team measure rates of synaptic pruning? “Conventionally, synaptic pruning is measured by cutting mouse brains into super-thin slices, staining the microglia and synaptic proteins, and imaging them under a microscope,” says Beth. “However, this method is slow and not well-suited to the complex brain circuits we’re interested in.” To address this, the team has developed better methods. “In one method, we purify the microglia from a mouse brain, stain the synaptic proteins within them, and measure the synaptic protein signal with a method called flow cytometry,” explains Matthew. “This allows us to quantify the engulfment of synapses of thousands of microglia from many mice in one experiment.”

But there are challenges with using mice to study human diseases. “Mouse brains are much simpler than human brains, and they develop in different ways,” says Beth. “Importantly, it’s unclear which stage of mouse development corresponds to human adolescence.” While mice are typically considered ‘adult’ once they reach sexual maturity at two months old, the team found that mouse behaviours and neural pathways continue to change dramatically between two and six months of age, suggesting that they are still developing in this time. “This led us to conclude that this age range may serve as approximately analogous to human adolescence,” says Matthew.

Delving deeper

The team is also measuring C4A and other proteins in samples from human volunteers with and without schizophrenia to identify which patients are affected by specific mechanisms, such as excess synaptic pruning. By studying both mice in the lab and human patients, the team endeavours to improve understanding of how effective the mouse model system is for studying human adolescent brain development. The aim is to increase the chances of basic research results being translated to human drug development efforts.

Matthew, Beth and their colleagues are exploring other molecular goings-on, too. “We’ve found that another schizophrenia risk gene, CSMD1, also affects C4A activity and synaptic pruning,” says Beth. “This is important because it shows how two different genetic risk factors converge on a single molecular pathway.” The team’s work on CSMD1 is in its early stages, but is already proving rewarding, as the CSMD1 gene may be a better target for treatments than C4A. “C4A is a critical part of the immune system throughout the body, so it might be risky to target C4A with a drug,” explains Matthew. “CSMD1, on the other hand, is mostly expressed in the brain, so may be a better therapeutic target.”

This leads to the overall aim of the team’s research – to provide scientific evidence of the neurobiology underlying schizophrenia, which can be used to develop new drugs to treat the disease. “We hope that some of what we learn will uncover new therapeutic targets, such as proteins that could be targeted by new drugs,” says Beth. With this evidence in hand, Beth and Matthew hope that schizophrenia will become a better-understood, and therefore more treatable, disease.

Dr Matthew Johnson

Dr Matthew Johnson

Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, USA

Dr Beth Stevens

Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard; Boston Children’s Hospital; Howard Hughes Medical Institute, USA

Field of research: Neurobiology

Research project: Investigating whether excessive synaptic pruning during adolescence causes schizophrenia

Funders: US National Institutes of Health (NIH); Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research; Howard Hughes Medical Institute

Websites: stevenslab.org; broadinstitute.org/stanley-center-for-psychiatric-research

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM670

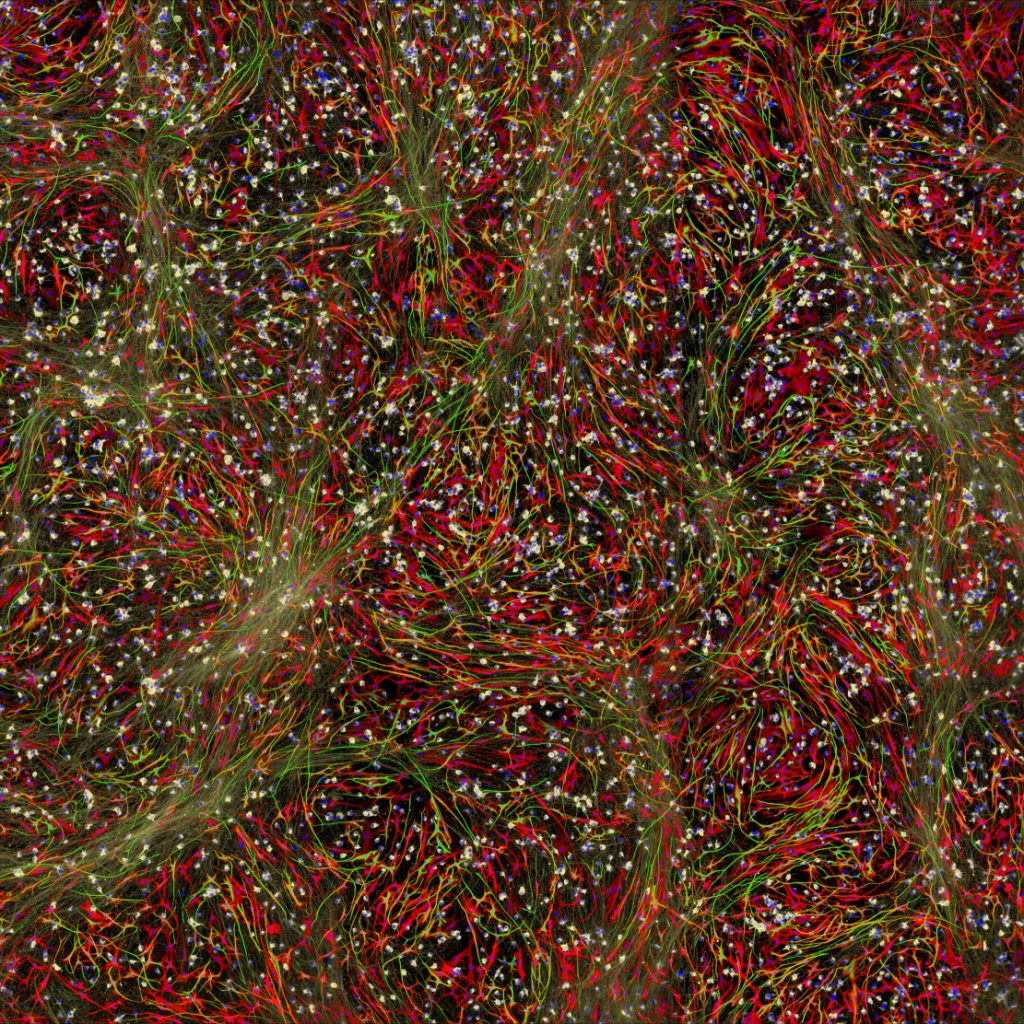

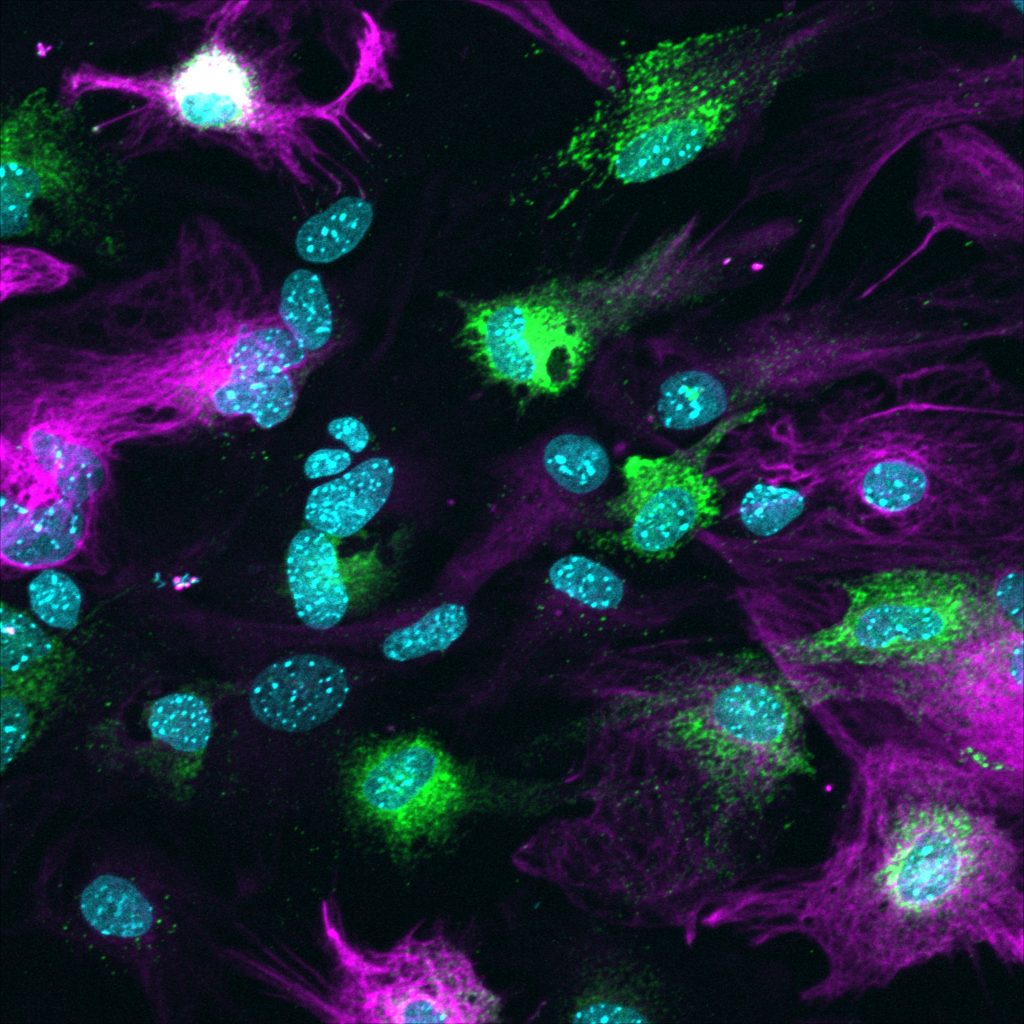

As elevated levels of C4A in the human brain are linked to increased schizophrenia risk, the team generated a mouse model to study how human C4A protein interacts with different brain cell types, such as astrocytes (a type of glial cell). In this microscope image, mouse astrocytes are pink, cell nuclei are blue and human C4A protein is green.

© Cherish Taylor

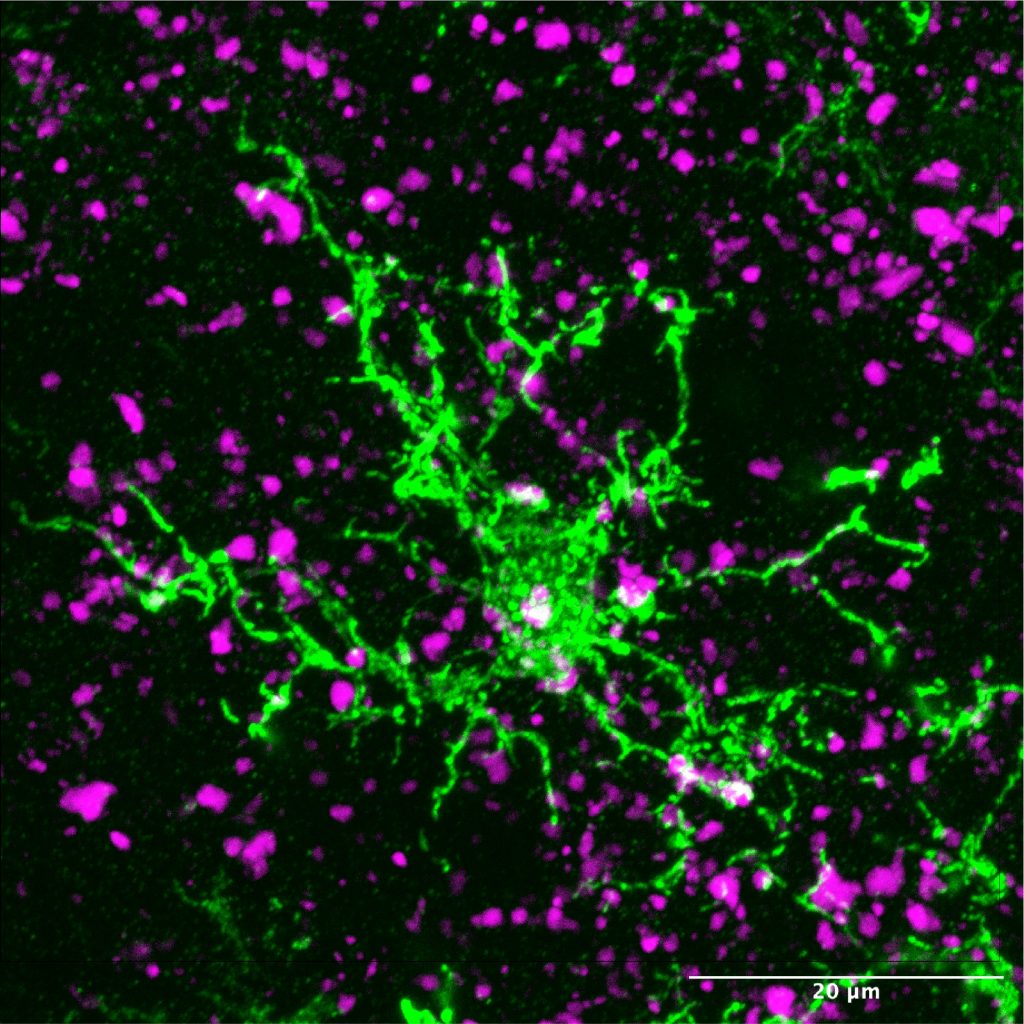

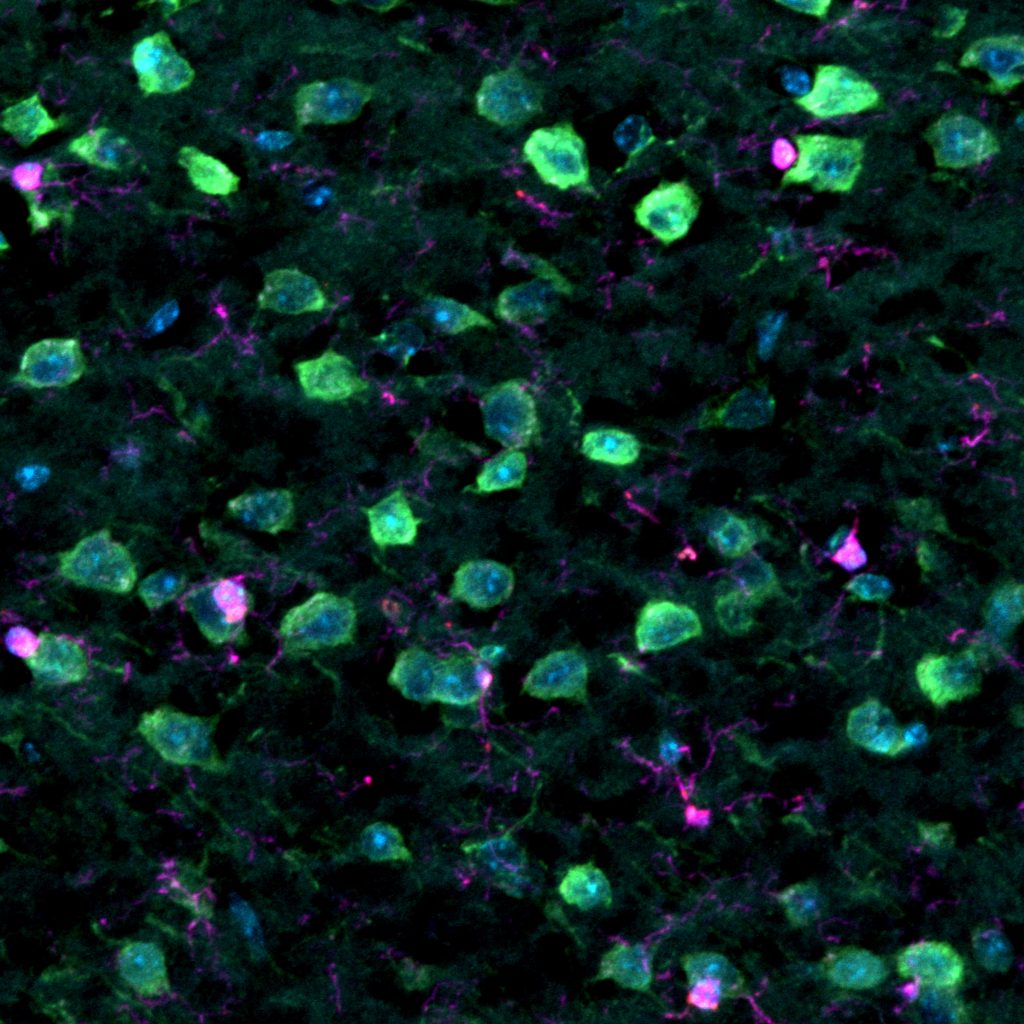

A microscope image of a mouse brain expressing the human C4A protein (green), showing microglia (pink) and cell nuclei (blue).

© Cherish Taylor

About neurobiology

Neurobiology is the study of the nervous system, which consists of the brain, spinal cord and nerves. Matthew and Beth specialise in neuroimmunology – the study of the interactions between the nervous system and the immune system. “We collaborate with immunologists, physiologists, molecular and cellular biologists, geneticists, and behavioural and computational neuroscientists,” says Beth. “This level of collaboration is critical, allowing us to leverage everyone’s expertise to make progress against the significant challenges presented by psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia.”

Despite decades of research, the overwhelming complexity of the human brain means that scientists have barely scratched the surface of neurobiological understanding. “Unlike treatments for diseases in other parts of the body, we tend not to take tissue samples from the brain,” says Matthew. “So, we rely on indirect study using methods like neuroimaging or taking samples of blood or spinal fluid that contain proteins that correlate to brain activity.” Neurobiologists also rely on mouse models to understand human brains, but this comes with challenges due to the differences between mice and humans.

New technologies are creating opportunities to address the challenges of studying living human brains. “Non-invasive techniques to image live brains (like positron emission tomography or ‘PET scans’) continue to advance, as do proteomics techniques that can measure thousands of proteins in tiny samples,” says Beth. “Geneticists are also making a lot of progress in uncovering the genes behind diseases, including schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders, creating genetic ‘roadmaps’ that can help find new drug targets.” These advances set the stage for a new chapter in neurobiology – one that will uncover surprising secrets about the incredible organ that is the brain.

Pathway from school to neurobiology

At high school, useful subjects to study include biology, chemistry, mathematics, physics and computer science. These can be complemented by arts and humanities subjects for a more well-rounded understanding of human society and challenges that need addressing.

At university, study a degree in neuroscience, cell biology or molecular biology.

Look for opportunities to work in a neurobiology (or general biology) lab to gain practical research experience. “As a young scientist, this hands-on experience is vital for you to apply the concepts you have learnt in the classroom,” says Matthew. “It will also allow you to learn about research as a potential career.”

“Attend public talks and events at universities,” advises Beth. “These offer another way to be immersed in science.” For example, if you are based in Boston, the Harvard Brain Science Initiative (brain.harvard.edu) hosts exciting events and provides excellent resources. Dr Cherish Taylor, a member of Beth’s team, recommends attending the Black in Neuro (blackinneuro.com) seminars to hear from Black researchers working in all aspects of the field.

Explore careers in neurobiology

The Broad Institute, where Matthew and Beth work, offers summer programmes for high school and undergraduate students to participate in cutting-edge research projects: broadinstitute.org/students/summer-research-programs

The Society for Neuroscience provides information about career paths in the field: neuronline.sfn.org/career-paths

“I would encourage all early career scientists to attend conferences run by neuroscience organisations,” says Matthew. “These are great ways to get more involved in neurobiology, and to network with scientists at all career stages and learn about different career opportunities and trajectories.”

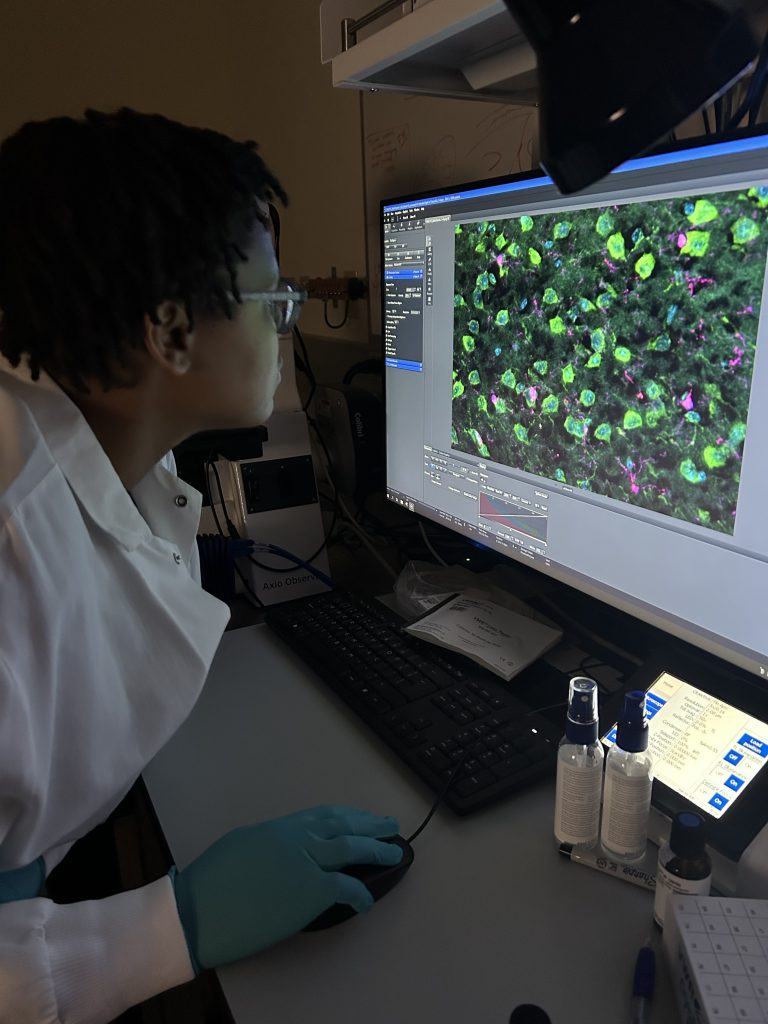

Meet Cherish

Dr Cherish Taylor is a researcher in Beth’s lab.

As a teenager, I wanted to become a forensic scientist. I was fascinated by how detectives in TV shows like CSI and Law and Order used science to solve cases. I also loved music – my brother is a musician, and I grew up going to his gigs. At one point, I also thought I would become a singer.

At college, I wanted to gain experience in genetic research to help my dream of becoming a forensic scientist. I joined a lab where we used optogenetics (a genetic tool that uses light to activate genes in genetically modified mice) to study how the brain influences behaviour. I was amazed by how the activity of tiny cells in the brain had such an impact on the mice’s behaviour. So, I changed my career goals and decided to study psychology and neurobiology.

Community in science is so important. I was the only Black woman on my PhD programme, and I felt isolated. When I met another Black woman on a different programme, we realised we were navigating the same challenges, so we started meeting for lunch once a week. Soon, other Black women joined us. We built the community we needed, which helped us persevere.

A day in the lab can vary a lot. I might be at the bench doing an experiment, in the animal facility working with mice, or on my computer processing results or reading about new science.

Science is hard. Often, experiments don’t go as planned, results are difficult to understand, or we lack the technology we need to test something. These moments can be frustrating and discouraging, so a critical characteristic for any scientist is the ability to persevere. We keep learning, repeating experiments, trying new techniques and reaching out to others. It’s important to surround yourself with good mentors and peers who can encourage you when things are challenging and help you see things from a different perspective. I’m proud to act as a mentor for my students, and to see their growth and development.

The brain is an amazing organ, but we still know so little about it. This means that neurobiology is really exciting because our discoveries make new knowledge – we are rewriting the textbooks!

Cherish’s top tips

1. Stay curious. If you’re interested in something, learn about it. And reach out to scientists doing work you find cool! Most would be happy to talk to you about their work.

2. Seek research experience. Hands-on experience is key to becoming a scientist, so actively participate in class labs, shadow a researcher or find a summer research placement.

Do you have a question for Matthew, Beth or Cherish?

Write it in the comments box below and they will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

Neuroscientists are investigating how impairments in a person’s ability to form memories could lead to schizophrenia:

futurumcareers.com/the-importance-of-memory-in-severe-mental-illness

0 Comments