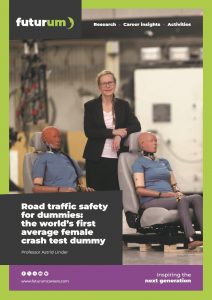

Combining textile technology with healthcare entrepreneurship for human dignity

When we think of health, we tend to think about the physical aspects – being free from pain, illness or injury. However, there is also experiential health – how we feel about and experience our own health. One aspect of experiential health is dignity, which can be a problem for women with low resources around the world when it comes to menstrual hygiene. Dr Karin Högberg and Nils Lindh of the University of Borås, Sweden, have designed an innovative new sanitary pad designed to be durable, hygienic and easy to clean, providing dignity for women and girls who desperately need it.

Talk like a healthcare entrepreneur

3D encapsulation — a method of trapping liquid inside a three-dimensional network of small pockets instead of absorbing it into fibres

Biocide — a substance that kills or controls harmful organisms such as bacteria

Experiential health — how an individual experiences their own physical and mental health

Filament fibre — a long, continuous strand of fibre that can run for many metres without breaking

Hydrophobic — something, such as a fabric, that repels water and, therefore, does not get wet easily

Incontinence — lack of bladder control

Menstruation — often referred to as a ‘period’, the regular discharge of the uterus lining (and blood and tissue) through the vagina

Patented — legally protected so that only the inventor or company which owns the patent has the right to make or use the invention

Staple fibre — a short fibre, up to only a few centimetres long, that is spun with other staple fibres to produce a longer thread

WASH — water, sanitation and private spaces

From mood changes to cramping, fatigue and aches, having a period can be mentally and physically challenging. In addition, many women and girls have limited financial resources available for sanitary products, making periods difficult to cope with. To compound matters, menstruation is stigmatised in many parts of the world, leading to lack of knowledge and support, feelings of shame and humiliation, and the use of rags or fabric scraps instead of hygienic and purposefully designed sanitary products. For the many women worldwide who lack clean running water, sanitation or private spaces (collectively known as WASH), menstruation is incredibly difficult to manage.

To tackle this, Dr Karin Högberg and Nils Lindh with colleagues at the University of Borås created Spacerpad, a reusable, sustainable sanitary pad, designed to be effective in low-resource environments. “We believe in everyone’s equal right to a dignified life,” says Karin. “In all cultures, sanitary hygiene is expected to be done in private, which is difficult for the millions of women worldwide who lack the right conditions. Being able to discreetly take care of your most private hygiene is important for feeling decent and dignified. The opposite is shame, which is one of the most humiliating things a human can experience.”

Karin and Nils’ work is guided by the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which includes goals such as Clean Water and Sanitation, and Reduced Inequalities. Nils says, “We are primarily targeting the 88% of the world’s fertile women who do not have an abundance of financial resources, and women who lack safe access to water or sanitation solutions.”

What is Spacerpad, and how is it made?

“Spacerpad is a high-tech, hygienic and durable sanitary pad that holds liquid using 3D encapsulation instead of absorption,” explains Karin. In traditional pads, the liquid is either absorbed into the fibres themselves or into highly absorbent disposable materials. In Spacerpad, menstrual fluid is captured inside tiny three-dimensional pockets formed by hydrophobic filaments, and a patented barrier stops it from leaking.

The pads are made from filament fibres, which are long, continuous strands of material, rather than from staple fibres which are incredibly short fibres that are spun together to create a continuous thread. “Filament fibres are stronger, smoother and less likely to retain particles than staple fibres,” explains Karin. “The liquid-holding core of Spacerpad consists of 100% polyester filament structures, making it quick-drying, easy to clean, and hygienic for repeated use.”

This innovative approach makes Spacerpad durable, lightweight, breathable and capable of holding large amounts of fluid. “The pads are easy to clean with a small amount of water and soap, and dry quickly because water isn’t trapped,” says Karin. “The small water residues can be manually squeezed away with a piece of fabric, preferably made from staple fibres of natural materials as these absorb water effectively.” This means that only two to four pads are needed for a full period, and with careful use, a pad can last several years, making each Spacerpad very cost-effective.

How is Spacerpad overcoming the limitations that many of todays’ sanitary products have?

Reusable sanitary products exist, but they often leak, smell, or are difficult to clean and dry. To prevent odour, Spacerpad includes a silica spray. Karin explains, “Silicon dioxide, or silica, is one of the most common minerals on Earth. It exists naturally in forms like quartz, and it’s safe for people and the environment.”

Another key concern is safety. “A lot of reusable sanitary products are treated with biocides, such as silver ions, copper zeolite and zinc oxide, which are harmful to the environment and to wildlife. Some are even hormone-disrupting for humans,” says Karin. “Our alternative to antibacterial additives is to eliminate the basis for what can become a bacterial growth, by offering a product that is truly easy to clean with only a small amount of water and soap or detergent, and which dries quickly, minimising the risk of moisture during reuse.”

What challenges did the development of Spacerpad involve?

Karin and her colleagues set themselves an ambitious target – to create a pad that worked like a menstrual cup. “One moment it should hold liquid, and the next moment it should release it, two contradictory properties which are tricky to combine,” says Karin. “The solution involves considering the materials and how they are constructed – that is, the production of the pad.”

Beyond the creation of Spacerpad, there was the challenge of how to get Spacerpad to the target group – women with the fewest resources. These women do not have money to spend on expensive products, but technological innovation is not cheap. So, Karin and Nils created ways to remove this financial barrier. “We have worked extensively with different business models to make Spacerpad accessible to more people,” explains Nils. “These include a ‘buy one, give one’ concept, enabling those who can afford it to donate a Spacerpad to someone who cannot, and facilitating local production in low-income areas.”

What’s next for Spacerpad?

The next exciting step is getting Spacerpad out to the women who particularly need it. Karin and Nils hope Spacerpad will be available in India and parts of East Africa in early 2026. Beyond that, Nils says, “One can always continue to research and develop, but we must choose how best to use our resources. Instead of product development, I think we will look more at how we can build local production and distribution in a sustainable way.”

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM666

Sven, Lars, Karin, Ulrika and Sebastian who together designed the Spacerpad production machine.

All photos © Spacerpad

Dr Karin Högberg

Dr Karin Högberg

Senior Lecturer, Department of Textile Technology, Faculty of Textiles, Engineering and Business

Nils Lindh

Sustainability Coordinator

University of Borås, Sweden

Fields of research: Healthcare; textile technology

Funder: Swedish Governmental Agency for Innovation Systems (Vinnova)

Website: spacerpad.org/en

About healthcare entrepreneurship

Karin and Nils’ work in healthcare entrepreneurship and textile technology requires skills such as creativity, problem-solving, perseverance and business sense, as well as specific knowledge about a field. Karin says, “I have a research brain and a heart for development that benefits the people at the bottom of the economic pyramid.”

Karin and Nils are passionate about supporting dignity. Karin says, “Health has a physical dimension, but experienced health goes further than that – the deepest depths of human experience, where issues like dignity become central.”

Bringing their vision for Spacerpad to life has required practical innovation. Spacerpad holds fluid rather than absorbs it, needing heat-and-pressure assembly without squashing, so they created a specialised machine for this process. Smart solutions, such as moving production to the areas where the product is needed, will help get Spacerpad to low-income women and support local economies while still covering production costs. “Local manufacturing enables ownership and job opportunities,” says Nils.

Karin and Nils have also devised ‘Spacerpad It Forward’ (SPIF). “SPIF is a social innovation with a simple core idea: ‘Buy a pad, pay for a pad for a sister’,” explains Nils. “Each purchase funds a Spacerpad for a woman who cannot afford one, and in high-income regions like Europe, buyers pay more to support women in low-income countries. SPIF aims to transform menstrual health access into a shared responsibility, bridging gaps between economic classes and empowering women worldwide.”

Healthcare solutions are needed in different areas of personal hygiene. “Activism around the phenomenon of menstruation has been very positive and has broken down many taboos,” says Karin. “However, incontinence, especially in a resource-poor settings, needs similar solutions – discreet, affordable products, safe washing and drying facilities, and respect for dignity. Addressing this requires entrepreneurial vision.”

Pathway from school to healthcare entrepreneurship

At school, make sure you develop a good foundation in the sciences, to understand technology and people’s physical needs, and humanities, to understand people and societies.

To develop products similar to Spacerpad you may want to study textile technology at university.

“If you want to work on developing menstrual hygiene solutions, or how people can be lifted out of poverty, there are many entrances and, therefore, a huge range of educational opportunities,” says Karin. “You may be more drawn to natural sciences or social sciences. Either way, it is of great value if you can collaborate across both areas.”

Explore careers in healthcare entrepreneurship

You can learn more about the work of Karin, Nils and their colleagues at the University of Borås in Sweden here.

“The Swedish School of Textiles, part of the University of Borås, hosts open house events and provides online guidance sessions,” says Karin. “For international audiences, the Swedish School of Textiles offers webinars and digital resources about studying in Sweden.”

The Textile Institute is an international professional organisation for people working in the textile industry. Its website provides courses as well as all the latest news and information about the field. You could even consider becoming a student member which would get you access to resources, career support and events.

Meet Karin

I was inspired to pursue nursing by the desire to make a tangible difference for people who really are in need of support.

I was inspired to pursue nursing by the desire to make a tangible difference for people who really are in need of support.

You can develop ideas based on technical possibilities or based on human needs. The need I have based my work on is existential – the human need for dignity.

My strongest driving force is a ‘moral ambition’, something the Dutch historian Rutger Bregman writes about in his book with the same name. He argues that people should use their talents not just for personal gain but to tackle the world’s problems, and I encourage others to embrace this same ambition. It is possible to shift from “someone should…” to “I will do it…”.

My proudest career achievement is not giving up on the idea of simplifying life for those who almost always end up last in priority – women and girls living in poverty.

We have not yet reached our goal of having the smartest products reach those with the greatest actual need. So, it will remain!

Karin’s top tips

1. If the issue you focus on is ethically significant, for humanity, society or the environment, then I believe you can have more energy and can manage to do and achieve more. It is also easier to get others interested in what you are doing, which is important so that you can build a team.

2. Working in a team is important because you need different skills, but also because it allows you to find enjoyment and stay motivated.

Meet Nils

I grew up in Kenya, spending 10 of my first 16 years there. Experiencing its nature, cultures and challenges sparked my interest in sustainability and led me to study environmental sciences and business. After working for environmental authorities, I joined a small development organisation where I shaped partnerships in Africa, expanded projects and developed strategies.

I grew up in Kenya, spending 10 of my first 16 years there. Experiencing its nature, cultures and challenges sparked my interest in sustainability and led me to study environmental sciences and business. After working for environmental authorities, I joined a small development organisation where I shaped partnerships in Africa, expanded projects and developed strategies.

My eureka moment came when I realised that aid often creates dependency, while learning empowers change. This insight drove us to design strategies focused on learning processes, entrepreneurship and local ownership – while embracing patience and clear communication. These principles continue to guide my work, including in the Spacerpad project.

My proudest achievement is realising the transformative power of learning and building strategies around it – creating approaches that foster ownership, entrepreneurship and sustainable impact.

My aim is to see Spacerpad succeed and improve the lives of underserved women and girls globally.

Nils’ top tips

1. Understand that sustainability is complex, so keep an open mind and practise patience.

2. Focus on people. Recognise that we all have needs and biases, and prioritise learning as a way to move forward together.

Do you have a question for Karin and Nils?

Write it in the comments box below and they will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

Read about the world’s first average female crash test dummy:

futurumcareers.com/road-traffic-safety-for-dummies-the-worlds-first-average-female-crash-test-dummy

0 Comments