Using creative arts to address children’s eco-anxiety

As the climate and biodiversity crises worsen, predictions about the future are becoming increasingly gloomy. This has a profound effect on people’s mental health, especially children. A team of Canadian researchers, including Dr Catherine Malboeuf-Hurtubise, Dr Catherine Herba and Dr Jonathan Smith, are exploring how creative arts can help children address eco-anxiety and equipping teachers to better support their students’ climate concerns.

Glossary

Collective action — shared action taken by a group of people to achieve a common goal

Competence — a person’s sense that they have an effective impact on their environment

Eco-anxiety — the positive and negative emotions, thoughts and behaviours related to the climate crisis

Radical hope — acknowledgment of the painful realities facing humanity without giving up, while holding onto the belief that a better future is possible

Self-determination — the ability of a person to take control of their own life and to act of their own will and in accordance with their values of what is important

Eco-anxiety is a growing phenomenon with potentially profound psychological effects. A team of Canadian researchers has assembled to develop and test methods that schools can use to address eco-anxiety in their students – not to diminish it, but to help children understand their thoughts and emotions about climate change and translate them into positive action. Through creative arts and philosophical enquiry, the team is empowering children and teachers alike to address eco-anxiety and its effects on mental health.

What is eco-anxiety?

“Eco-anxiety refers to any lived experience – be it emotions, thoughts or behaviours – related to an awareness of climate change and the corresponding uncertainty of the future. This may include anger at political inaction, feelings of individual helplessness or hope for a brighter future,” explains Dr Catherine Malboeuf-Hurtubise, a clinical psychologist and professor at Bishop’s University. “It’s really important to understand that eco-anxiety is not a problem, but rather a normal response to a truly difficult reality.”

Everybody experiences eco-anxiety in a different way. “While some people are not really concerned about climate change, others are very much so,” says Dr Catherine Herba, a professor of psychology at the Université du Québec à Montréal. “People react in different ways to the climate crisis. For example, some take action while others feel hopeless.” There are concerns that eco-anxiety is affecting mental health, especially for young people – which indicates the need for intervention.

Eco-anxiety in children

While there is a fair amount of research into eco-anxiety in teenagers, there is little focus on younger children, which prompted the team’s research. “We explore eco-anxiety in children to understand whether they experience eco-anxiety, and if so, how they experience it,” says Dr Jonathan Smith, a professor of education at the Université de Sherbrooke. The team encourages teachers to open discussion spaces for their students, providing an opportunity for those experiencing eco-anxiety to speak up and explore their concerns.

Through such efforts, the team found that, in general, young children have a good knowledge of climate change and its consequences, gleaned from sources at school, through the media and from discussions with parents and friends. “This awareness is linked to emotions, such as sadness for humans and animals that are suffering, anger towards polluters and the inaction of previous generations, and fear for their own future,” says Catherine Malboeuf-Hurtubise. “However, they also experience hope and connection with others, through taking collective action and the knowledge of technologies that can help mitigate the consequences.”

Why is eco-anxiety difficult to address?

Eco-anxiety can often be hidden, and even parents may not realise that their children have feelings about climate change. “Children tend to cope by avoiding the issue, which is not very adaptive in the long run,” explains Catherine Herba. “We suggest that parents and teachers bring conversations about climate change and eco-anxiety into the home and classroom and encourage children to act in meaningful ways at home and school.” Catherine suggests encouraging children to spend time in nature, watch documentaries and read children’s books on climate change. Parents or teachers can then prompt discussions of the themes and concerns that arise to build an appreciation of eco-anxiety while also addressing its mental impacts.

One challenge that both parents and teachers often face is that they do not feel well-equipped to facilitate discussions on topics that are causing children distress, worrying that such conversations may add to their anxiety – but avoiding or playing down the issue can make things worse. “If an adult doesn’t acknowledge a child’s emotional response to climate change, then the child doesn’t feel heard and feels their emotions and thoughts are not validated,” explains Jonathan. “Saying that ‘everything will be fine’ does not validate a child’s concerns.”

The importance of addressing your own eco-anxiety

Before you can facilitate discussions about climate change and eco-anxiety as a teacher, it is important that you explore your own experiences and emotions about the issue. “Reading up on the topic, cultivating self-care, finding your own meaning, and building a constructive and radical hope can help equip you with the tools needed to help your students,” says Catherine Malboeuf-Hurtubise. “Without this prior work, it’s difficult for teachers to accompany children on their own journey of understanding their eco-anxiety.”

The team emphasise that eco-anxiety is an understandable reaction to the modern world and efforts should focus on helping children cope with eco-anxiety, rather than reducing it. “We want to facilitate effective and positive coping strategies that can be linked to positive action,” says Catherine Herba. “These strategies include self-care, grieving, recognising and engaging with our emotions, and finally, empowerment to action.”

A creative arts intervention for eco-anxiety

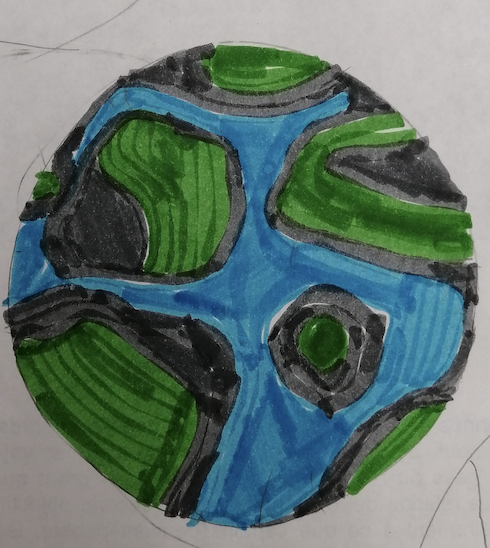

To help address eco-anxiety in children, Catherine, Catherine, Jonathan and their colleagues have developed an intervention combining creative arts and philosophical enquiry, which aims to improve children’s well-being and mental health by allowing them to explore their emotions related to eco-anxiety. During the eight-to-ten-week-long programme, the team visits classrooms weekly to lead art workshops and initiate philosophical discussions related to the themes of climate change and eco-anxiety.

“It is well-known that making art can help children develop critical thinking skills for their emotions and thoughts,” explains Jonathan. “Using creative expression as a catalyst for group discussions, we address themes such as emotional reactions to climate change, the beauty of nature, our responsibility for nature, the awe-inspiring power of nature, taking care of ourselves and the planet, and citizen engagement.”

The importance of philosophy

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM474

In addition to encouraging children to create artwork inspired by these themes, the team also encourages philosophical enquiry. “The contribution of philosophical enquiry with children before, during and after the artistic process is related to art’s benefit on youth mental health,” explains Catherine Malboeuf-Hurtubise. “It encourages children’s questioning and introspection related to the art they create, helping them put the intuitive process of artmaking into words.” This combination of philosophy and art provides children with the space to explore any doubts they have around the creative process, such as performance anxiety and fear of judgement from others. “We are evaluating one hypothesis about whether the combination of art and philosophical enquiry has a greater impact on children’s well-being, mental health and self-determination than either activity on its own,” explains Catherine Herba.

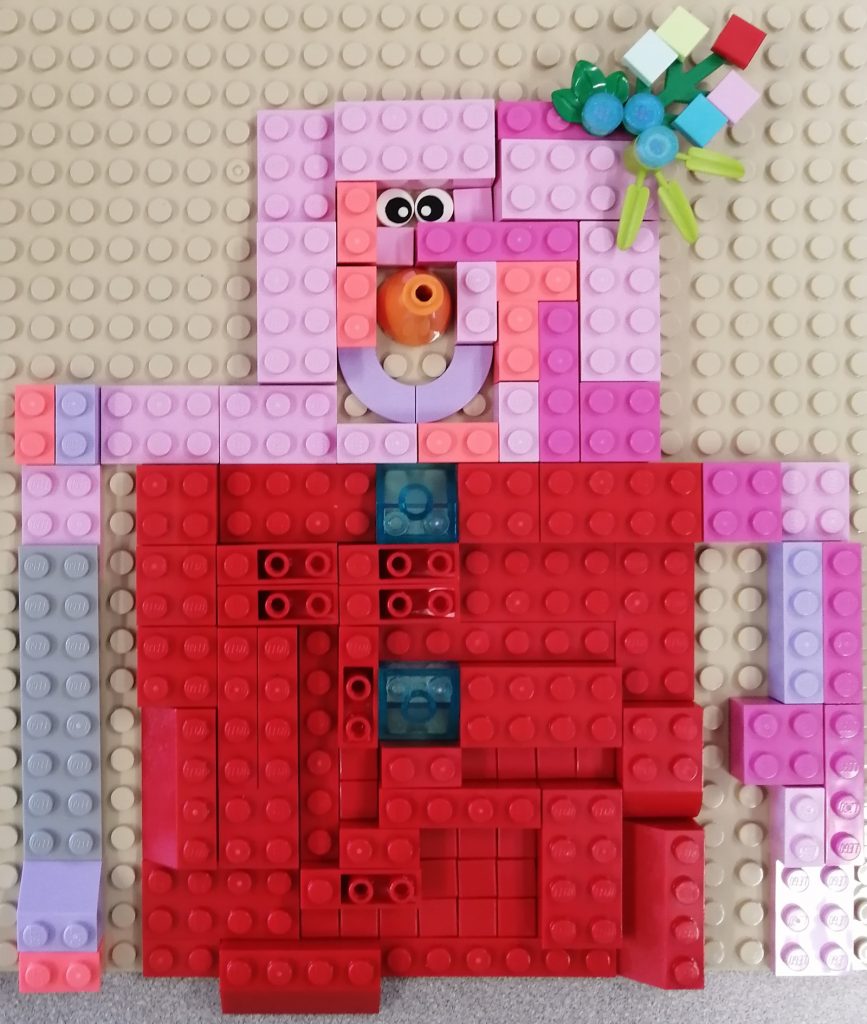

The importance of using different media

When delivering the art intervention in classrooms, the team employs various artistic media, with the aim of ensuring there is something that appeals to everybody. “Some children prefer fine arts, such as painting or drawing, while others prefer photography, sculpture, building with LEGOTM or dancing,” says Jonathan. “By introducing different forms of art, we allow children to open themselves to new experiences, express themselves non-verbally, and permit them to use whatever art form best suits them to explore their feelings about the climate crisis.”

How do children respond to the intervention?

While the team’s research project to scientifically evaluate the impacts of their art intervention is still ongoing, preliminary results are promising. “We conducted a pilot study with a class of nine-year-old children, during which our combined intervention of art and philosophy was well-received by the students and their teacher,” says Catherine Malboeuf-Hurtubise. Students reported that the topic of climate change was important to them and that they wanted to understand and explore their eco-anxiety. “The children most enjoyed the photography activities as they had fun using cameras to take photos, were enthused to share their photos with their classmates, and reacted with joy to seeing their classmates’ pictures,” says Catherine Herba. “The teacher also noted that the photography activities sparked the most profound discussions on climate change.”

After the intervention, the children reported increased psychological satisfaction in several aspects. “Overall, the art intervention fostered the basic psychological need for self-determination in children, namely through the freedom to choose which discussions to pursue, and because they found the themes important to them,” says Jonathan. “They also reported satisfaction in the psychological need for competence, as they were able to overcome challenges around speaking in front of the group, and felt they were becoming better at their chosen art media as the weeks went by.”

Advice for teachers

Catherine, Catherine and Jonathan emphasise that while addressing students’ eco-anxiety can feel daunting, they believe the outcomes will be well worth it. “Schools are an important space where children should not be shielded from the reality of climate change, but be given spaces for emotional expression and collective action,” explains Catherine Malboeuf-Hurtubise. “As a teacher, you are in an important position where you can discover the concerns of children and help address them.”

While collective action should be encouraged, the team notes that this should be in partnership with self-care and emotional expression. “There is a danger that people can experience ‘activist’s burnout’ when they don’t take sufficient self-care measures,” says Catherine Herba. “Young people should learn how to identify their limits so they don’t become overly anxious and burnout, and how to act in a meaningful way without getting overwhelmed. The same also applies to teachers.” Embracing the idea of ‘radical hope’ can help – accepting the painful realities facing humanity while still holding onto the belief that a better future is possible and taking action to imagine and work towards this future.

Adoption of this approach can be assisted through emphasising how seemingly small individual actions can collectively add up to a big impact. Schools can be a powerful place to actively demonstrate that positive change is possible. “Schools should be models to show children that society is making changes for their future,” says Catherine Herba. “This can be through measures such as composting, reducing single-use plastics and creating green spaces.” The team has noted that gardening is growing in popularity in schools, which can help children form a closer relationship with the natural world. “Teachers are always on the lookout for new knowledge and trends in educational practice,” says Jonathan. “They can facilitate the changes that can help children cope with eco-anxiety and feel empowered to take action.”

Dr Catherine Malboeuf-Hurtubise, Department of Psychology, Bishop’s University, Canada

Dr Catherine Malboeuf-Hurtubise, Department of Psychology, Bishop’s University, Canada

Fields of research: Child clinical psychology, child mental health, psychology of the arts, philosophy for children, existential psychology

Dr Catherine Herba, Department of Psychology, Université du Québec à Montréal, Canada

Fields of research: Developmental psychology, child mental health, parental mental health

Dr Jonathan Smith, Department of Preschool and Primary Education, Université de Sherbrooke, Canada

Fields of research: Educational psychology, social psychology, teaching and classroom management practices

Research project: Using creative arts to help children address eco-anxiety

Funders: Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), Ministry of Education of Quebec

Meet the team

Dr Catherine Malboeuf-Hurtubise

“I’ve been asking existential questions for as long as I can remember – I was ‘that’ child! Climate change is an existential threat that children must cope with, and I want to provide children with a safe space to do so. My expertise in existential psychology helps children navigate big questions, and I foster children’s self-determination in accordance with their values. These efforts can help children become flourishing and active members of their society.”

Dr Catherine Herba

“I’m interested in children’s socioemotional development, including early risk factors for internalising difficulties, such as anxiety, and externalising behaviours, such as aggression. I’ve also always been interested in how the well-being of a parent can be linked to the well-being and development of their child. I’m interested in the relationship between parents’ own eco-anxiety and that of their children, and how parents respond to their children’s concerns.”

Dr Jonathan Smith

“I study the quality of school adjustment to fit the needs of students, and how the influence of school and classroom factors affects the experiences of children. I’m also interested in how eco-anxiety affects children’s approaches to learning, and how interventions can be designed to help children manage their eco-anxiety.”

Do you have a question for Catherine, Catherine and Jonathan?

Write it in the comments box below and Catherine, Catherine and Jonathan will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

Read about the team’s research in this brochure aimed at students:

www.futurumcareers.com/how-can-creative-arts-help-children-cope-with-ecoanxiety

0 Comments