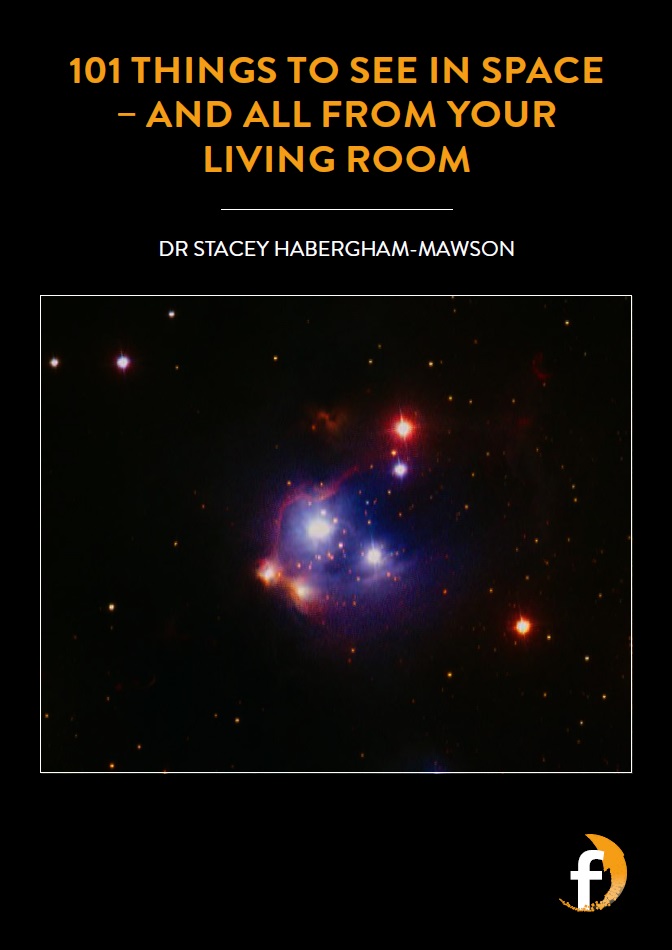

101 things to see in space – and all from your living room

What do you see when you look up at the night sky? Just a bunch of stars and the Moon? Maybe you can see the Big Dipper or Ursa Major. How about Orion?

Whether you can recognise and name the constellations or not, it’s pretty certain that at some point in your life, you’ll have looked up at the sky at night and wondered at the full Moon or the twinkling North Star.

Imagine, though, being able to look closer.

Imagine using the largest robotic telescope in the world and receiving pictures. What would you see? Sign up to the National Schools’ Observatory and you’ll find out

WHAT IS THE NSO?

The NSO is a free, online tool that gives people access to the Liverpool Telescope, both of which are run by Liverpool John Moores University. The aim is to use the wonders of space to inspire young people – you – to develop an interest in science, tech, engineering and maths (STEM) and to understand how these subjects can be applied to real-world applications. Although targeted at students and teachers, anyone can take part regardless of their age, background or where they live.

WHAT IS THE LIVERPOOL TELESCOPE?

The Liverpool Telescope is the largest robotic telescope in the world! In spite of its name, the Liverpool Telescope isn’t based in Liverpool, UK; it’s actually located on the island of La Palma in the Canary Islands, off the coast of Africa. This small, volcanic island has a much more reliable climate than Liverpool, which is important because the telescope can only work in clear and dry conditions.

There’s a small weather station attached to the telescope and this records temperature, humidity, wind speed, cloud coverage and barometric pressure. Depending on the results, this information signals the telescope to open or close. Luckily, the conditions on La Palma are usually good, and the telescope is generally open 80-90% of the year. But if there is snow or dust blowing over from the Sahara Desert, for example, the telescope will remain closed.

WHO USES THE LIVERPOOL TELESCOPE?

Professional astronomers use the telescope for 90% of the time. The remaining 10% is set aside for people like you – all you have to do is register for free. Dr Stacey Habergham-Mawson from Liverpool John Moores University in the UK is the chief astronomer working on the NSO project, and she – with her colleagues – are keen to open the Liverpool Telescope and the NSO to people everywhere and to all sections of society. For example, their videos have been translated into British Sign Language to improve accessibility.

WHAT CAN BE OBSERVED THROUGH THE TELESCOPE?

“Professional astronomers can apply for time on the telescope to measure a range of things,” says Stacey, and these include:

- Photometry (measuring the intensity of light)

- Spectroscopy (breaking the light down into different wavelengths that correspond to different chemical elements)

- Polarimetry (investigating the direction of light that hits the telescope from astronomical objects)

These are all complex subjects, but registered users who aren’t professional astronomers can observe the Moon, planets, star clusters, nebulae (dusty objects associated with the life or death of a star) and galaxies. In fact, the NSO has produced a catalogue, from which it’s possible to choose from several hundred astronomical objects to observe! Not only that but users can take images of these objects with the telescope’s photometry function.

DO YOU HAVE TO GO TO LA PALMA TO USE THE TELESCOPE?

Although the telescope is based in La Palma, registered users don’t need to go there. The idea is that people send the telescope a set of instructions. Of course, large telescopes such as this are extremely complex, so users are guided through the observation process. This ensures that the telescope doesn’t break; for example, pointing the telescope at bright objects in space for too long will damage the instrumentation.

WHAT HAPPENS AFTER THE TELESCOPE HAS RECEIVED INSTRUCTIONS?

Depending on the instructions it receives, the telescope will send back an image known as a FITS file. This file type has various advantages over a normal

image file, such as jpeg, because they can be manipulated; they allow accurate measurements of the light emitted from astronomical objects; and they allow the user to access “hidden” information such as weather conditions at the time the image was taken, the position of the object in the sky or how far away the object is. “What’s exciting is that people can do science with the image, just like the professionals,” says Stacey.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM13

WHAT IS THE NSO?

The NSO is a free, online tool that gives people access to the Liverpool Telescope, both of which are run by Liverpool John Moores University. The aim is to use the wonders of space to inspire young people – you – to develop an interest in science, tech, engineering and maths (STEM) and to understand how these subjects can be applied to real-world applications. Although targeted at students and teachers, anyone can take part regardless of their age, background or where they live.

WHAT IS THE LIVERPOOL TELESCOPE?

The Liverpool Telescope is the largest robotic telescope in the world! In spite of its name, the Liverpool Telescope isn’t based in Liverpool, UK; it’s actually located on the island of La Palma in the Canary Islands, off the coast of Africa. This small, volcanic island has a much more reliable climate than Liverpool, which is important because the telescope can only work in clear and dry conditions.

There’s a small weather station attached to the telescope and this records temperature, humidity, wind speed, cloud coverage and barometric pressure. Depending on the results, this information signals the telescope to open or close. Luckily, the conditions on La Palma are usually good, and the telescope is generally open 80-90% of the year. But if there is snow or dust blowing over from the Sahara Desert, for example, the telescope will remain closed.

WHO USES THE LIVERPOOL TELESCOPE?

Professional astronomers use the telescope for 90% of the time. The remaining 10% is set aside for people like you – all you have to do is register for free. Dr Stacey Habergham-Mawson from Liverpool John Moores University in the UK is the chief astronomer working on the NSO project, and she – with her colleagues – are keen to open the Liverpool Telescope and the NSO to people everywhere and to all sections of society. For example, their videos have been translated into British Sign Language to improve accessibility.

WHAT CAN BE OBSERVED THROUGH THE TELESCOPE?

“Professional astronomers can apply for time on the telescope to measure a range of things,” says Stacey, and these include:

- Photometry (measuring the intensity of light)

- Spectroscopy (breaking the light down into different wavelengths that correspond to different chemical elements)

- Polarimetry (investigating the direction of light that hits the telescope from astronomical objects)

These are all complex subjects, but registered users who aren’t professional astronomers can observe the Moon, planets, star clusters, nebulae (dusty objects associated with the life or death of a star) and galaxies. In fact, the NSO has produced a catalogue, from which it’s possible to choose from several hundred astronomical objects to observe! Not only that but users can take images of these objects with the telescope’s photometry function.

DO YOU HAVE TO GO TO LA PALMA TO USE THE TELESCOPE?

Although the telescope is based in La Palma, registered users don’t need to go there. The idea is that people send the telescope a set of instructions. Of course, large telescopes such as this are extremely complex, so users are guided through the observation process. This ensures that the telescope doesn’t break; for example, pointing the telescope at bright objects in space for too long will damage the instrumentation.

WHAT HAPPENS AFTER THE TELESCOPE HAS RECEIVED INSTRUCTIONS?

Depending on the instructions it receives, the telescope will send back an image known as a FITS file. This file type has various advantages over a normal

image file, such as jpeg, because they can be manipulated; they allow accurate measurements of the light emitted from astronomical objects; and they allow the user to access “hidden” information such as weather conditions at the time the image was taken, the position of the object in the sky or how far away the object is. “What’s exciting is that people can do science with the image, just like the professionals,” says Stacey.

- Knowing the size allows you to compare different astronomical objects and relate them to known objects like the Earth or the Sun.

- Discovering the colours provides information on the age of the object or the chemical composition of gas.

- Exploring the brightness allows you to compare stars in a system and work out how old the object is.

To open these FITS files, special software is required. Luckily, an easy-to-use version has been developed by the NSO team. Known as LTImage, the software can be downloaded for free, giving you all the tools you need to become an amateur astronomer.

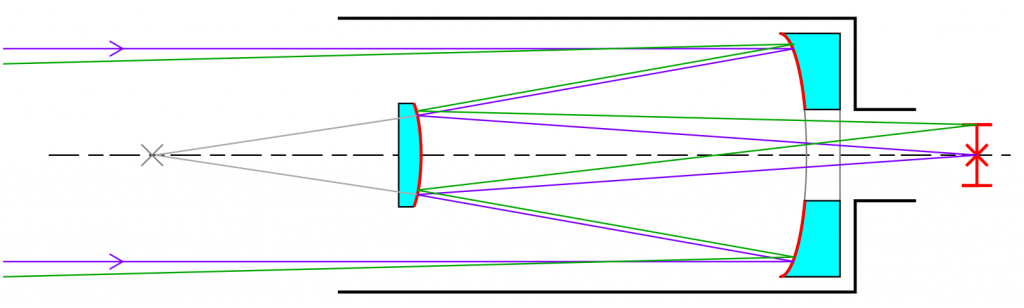

Telescopes collect and focus light from the night sky using either curved lenses (refracting telescopes) or mirrors (reflecting telescopes), or a combination of both. The bigger the lens or mirror, the more light the telescope can gather. A big telescope is therefore a big advantage!

The Liverpool Telescope uses mirrors: A huge, 2m diameter primary mirror reflects light onto a smaller secondary mirror, which focuses the beams of light onto a set of instruments. These include cameras to take images, and spectrographs which record the different wavelengths of light reflected onto them.

DR STACEY HABERGHAM-MAWSON

DR STACEY HABERGHAM-MAWSONManager of the National Schools’ Observatory (NSO), Astrophysics Research Institute, Liverpool John Moores University, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Astrophysics

RESEARCH PROJECT: The NSO is an online outreach project that gives people across the globe access to the Liverpool Telescope, the world’s largest robotic telescope. Users can program the telescope to take images of astronomical objects, which can be manipulated to give measurements and chemical compositions.

FUNDERS: Liverpool John Moores University; Science and Technology Facilities Council, Grant number ST/R000344/1

WEBSITE: www.schoolsobservatory.org/futurum

DR STACEY HABERGHAM-MAWSON

Manager of the National Schools’ Observatory (NSO), Astrophysics Research Institute, Liverpool John Moores University, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Astrophysics

RESEARCH PROJECT: The NSO is an online outreach project that gives people across the globe access to the Liverpool Telescope, the world’s largest robotic telescope. Users can program the telescope to take images of astronomical objects, which can be manipulated to give measurements and chemical compositions.

FUNDERS: Liverpool John Moores University; Science and Technology Facilities Council, Grant number ST/R000344/1

WEBSITE: www.schoolsobservatory.org/futurum

DID YOU ALWAYS WANT TO BE AN ASTROPHYSICIST?

No – I didn’t know what I wanted to be when I was younger. I had no idea that this existed as a job. I was the first (and so far, only) person in my family to go to university and, as a child, I decided that that was what I wanted to do. When I was 16, I started to wonder about what I would study. I got advice from a teacher to study something I was interested in so I applied for astrophysics because I thought space was really cool, and it was the part of physics that interested me most. When I started at university, I learnt more about the topic and I became hooked!

DO YOU HAVE TO BE GOOD AT A PARTICULAR SUBJECT TO STUDY ASTROPHYSICS?

Traditionally, all university courses (certainly in the UK) require students to be good at physics and maths. However, I’m always keen to show young people that the story doesn’t end there. Many people working in astronomy don’t necessarily have traditional backgrounds. I dropped maths in school because I didn’t see the point of it. You can always find a way; I did extra maths courses at university to get me up to the same level as everyone else. Also, many people working in this field have backgrounds in engineering or computer science – and don’t always have degrees. There are limitless possibilities if you have a drive to do something. We all follow different paths.

DO YOU THINK THAT WE WILL FIND LIFE ON OTHER PLANETS?

Yes – statistically it’s possible. We now think that almost every star hosts a planet, and we’ve discovered over 4,000 exoplanets in our galaxy, alone! The chances are, though, that if/when we find life it’ll likely be bacterial life. I don’t think that we’ll ever ‘meet’ another life form like us – there are too many coincidences we’d need for that to happen. We’d need them to be close enough to Earth to be able to communicate; we’d need them to have evolved enough to send communications or travel; and we’d need them to have done this at the same time as us. Life is short on the timescales of the Universe, and the distance between objects in space is unimaginable: Light takes 8 mins to reach us from the Sun, and 4 years from the next closest star – and that’s travelling at 300,000,000 metres per second! So, I don’t think we’ll have aliens knocking on the door, but I do think we’ll find evidence of life elsewhere.

WHAT MOTIVATES AND INSPIRES YOU?

I’m motivated by giving back. I know that physics is sometimes seen as being really hard and only suitable for certain groups (mainly well-off men), but the more I studied and worked, the further in my career I went. I’m not saying it’s easy, but it is doable. I know lots of people who would have been able to do the same thing, but we don’t all have the same opportunities in life. Many have to face an inordinate number of hurdles, put in their way by circumstance or other people. I want to try and make sure that I use the advantage I’ve been given to help pull other people over the hurdles. I do a lot of work in equality and diversity, and I work with young people to inspire them and raise their aspirations. This is what motives me – trying to make the world a little more equal in whatever small way I can.

WHAT OTHER INTERESTS DO YOU HAVE?

I’ve been a vegetarian since I was 11 and am very interested in how we can help the planet. I drive an electric car and always strive to learn more about renewable energy and technological advancements in my area. I love animals and gardening – I like to grow my own fruit and veg – and I generally like being in the countryside. My husband and I honeymooned in New Zealand, spending three weeks in a campervan and travelling around. I love almost everything about the country: We hiked on a glacier, swam with wild dolphins and did a skydive! I just love being in nature. I’m probably boring to most people, but I like what I like, and I know that those close to me like me for who I am.

Astrophysicists use their knowledge of physics and chemistry to study astronomical objects like planets, galaxies, the Sun and other stars, moons and nebulae. Essentially, astrophysics involves making observations and creating theories from these observations.

“There are so many reasons that young people should be interested in astrophysics,” says Stacey, “It allows you to be curious and ask questions, and begin to understand the way our world works and the fundamental laws that govern the entire Universe. There are also more practical reasons. Studying any type of physics gives you so many skills – numeracy, communication, logic, computing are just some of these – and you can apply these skills to tackle the world’s biggest problems, whether that’s in space or here on Earth. People with these skills, and a drive to do something with their lives, can really change the world.”

A degree in astrophysics can lead to many different careers. Some people continue working in the field, but others use the skills they have developed to pursue other careers in computing, finance, medicine and engineering, for example.

“In the UK, physics graduates generally earn more over their working life compared to most other degrees and are less likely to have periods of unemployment.” says Stacey “So, you’re learning about something exciting, and simultaneously gaining the skills to open many doors to future employment.”

- The National Schools’ Observatory runs an annual work-experience week for 16-18 year olds in July

- University of Kent runs an annual Space School for 15-18-year olds in August

- The University of Leicester runs a Space School annually for both 13-15 year olds, and 16-18s

- Astrophysicsgirl keeps an up-to-date, global list of summer schools in astrophysics

- Find out more about careers and work experience on the SpaceCareers website

- The average salary for an astrophysicist in the UK is £50-60K, but this varies widely in different sectors (academia / industry) and depends on experience.

You had me a Starship Enterprise! It is like GoogleEarth for space! Wouldn’t it be cool if schools ran space clubs to show those interested in the star systems things like this. Also Scouts and Guides could tap into this for their space badges.

Thank you for helping to make physics cool and accessible for our kids.

What a fascinating list! I never realized there were so many incredible things to explore in space without leaving my home. I especially loved the section on the different galaxies – the images you shared are breathtaking. Can’t wait to try out some of the suggested apps for stargazing! Thank you for the inspiration!