The relational determinants of health: An Indigenous journey to wellness

The belief that we are all intimately interconnected with the world around us and the beings that live in it is the foundational belief of many Indigenous nations around the world. For thousands of years, Indigenous Peoples of the lands and waters now known as Canada thrived and stewarded relationships with the land and its beings. However, European colonisers ruptured many of these relationships and inflicted, and continue to inflict, immense harms on Indigenous Peoples. For many years, Shelley Cardinal from the Canadian Red Cross and Debra Pepler from York University have worked alongside Indigenous communities, learning with them and co-creating resources to support them in understanding historical and ongoing violence and moving toward wellness.

Glossary

All My Relations — A foundational Indigenous belief that refers to the interconnectedness of all things, and the obligations that flow from those relationships

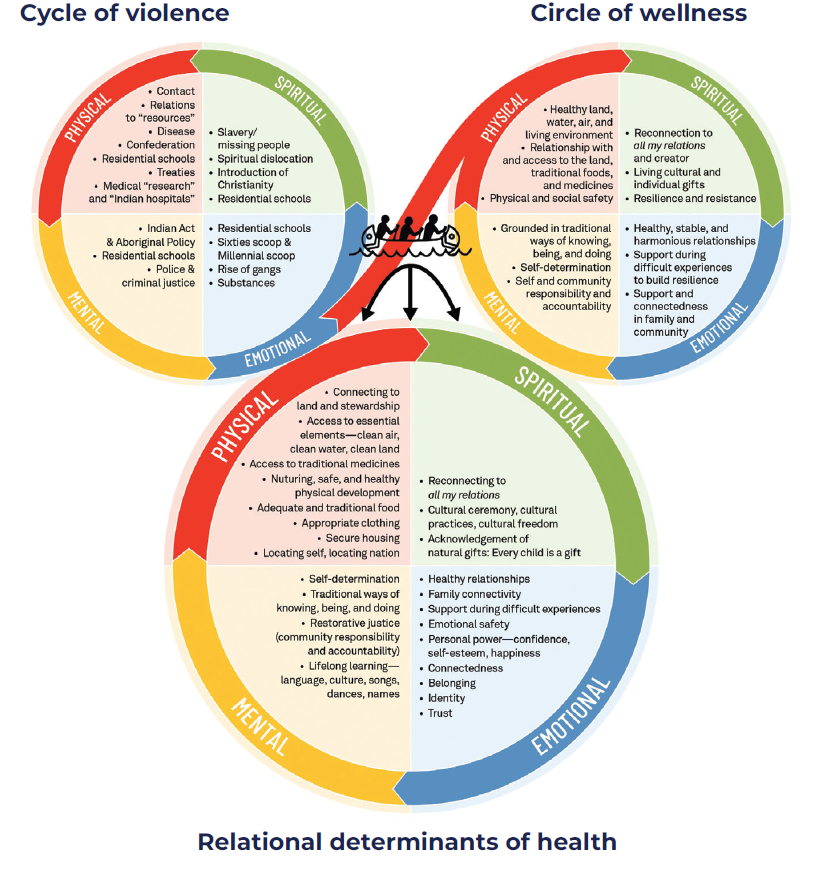

Circle of wellness — the physical, mental, emotional and spiritual dimensions that, when fulfilled, restore ‘All My Relations’ and return Indigenous communities to a place of health and well-being

Cycle of violence — the combined impacts of the many historical and ongoing harms inflicted on Indigenous communities by colonisers, disrupting ‘All My Relations’

Indigenous People — the people that inhabited a land from the earliest times, before the arrival of colonists

Relational determinants of health — the physical, mental, emotional and spiritual processes that help to restore traditional flows and ‘All My Relations’, supporting Indigenous communities to move from the cycle of violence to the circle of wellness

Traditional flows — Indigenous ways of being, knowing and doing

In Canada, Indigenous communities continue to overcome the past and present injustices that have disrupted their relationships with each other, the land they steward, and the plants, animals and resources they live in relationship with. By reconnecting these relationships, Indigenous communities are restoring their cultural strengths to continue thriving, in spite of the role that colonialism still plays in Indigenous communities and nations.

Shelley Cardinal from the Canadian Red Cross and Debra Pepler from York University have developed a model that aims to support Indigenous communities through their journey from the ‘cycle of violence’ to the ‘circle of wellness’. Their ‘relational determinants of health’ model clarifies the physical, mental, emotional and spiritual processes that Indigenous communities can use to restore their relationships and return to a place of health and well-being.

All My Relations

North America, known as Turtle Island by many Indigenous Peoples, is home to over a thousand Indigenous nations. While each of them has its own unique customs and traditions, many beliefs and values are shared across cultures. “All nations share the idea of stewardship,” says Shelley. “It is our responsibility to steward the land, caring for it and its beings, who help us thrive in return.” This philosophy is captured by the term ‘All My Relations’. “We live in relation to all beings, from the animals and water creatures to the birds that fly and the plants that grow on the land,” continues Shelley. “And when they thrive, we also thrive.”

‘All My Relations’ is at the heart of many traditional flows, a term used to describe traditional ways of being, knowing and doing. For millennia, these traditional flows defined the ways of being for Indigenous Peoples, guiding every aspect of their communities and supporting the wellness of their members. Traditional flows across Turtle Island were disrupted when Europeans began to colonise Indigenous lands, language and culture. While traditional flows emphasise connection, colonisation is a process of disconnection that ruptured the relationships that were so central to Indigenous communities’ well-being.

Layers of harm

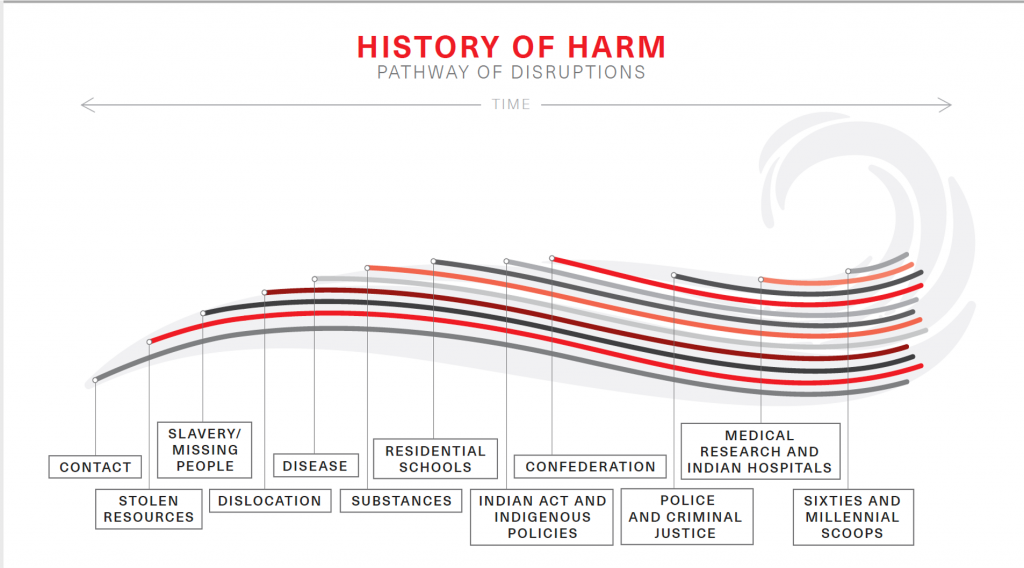

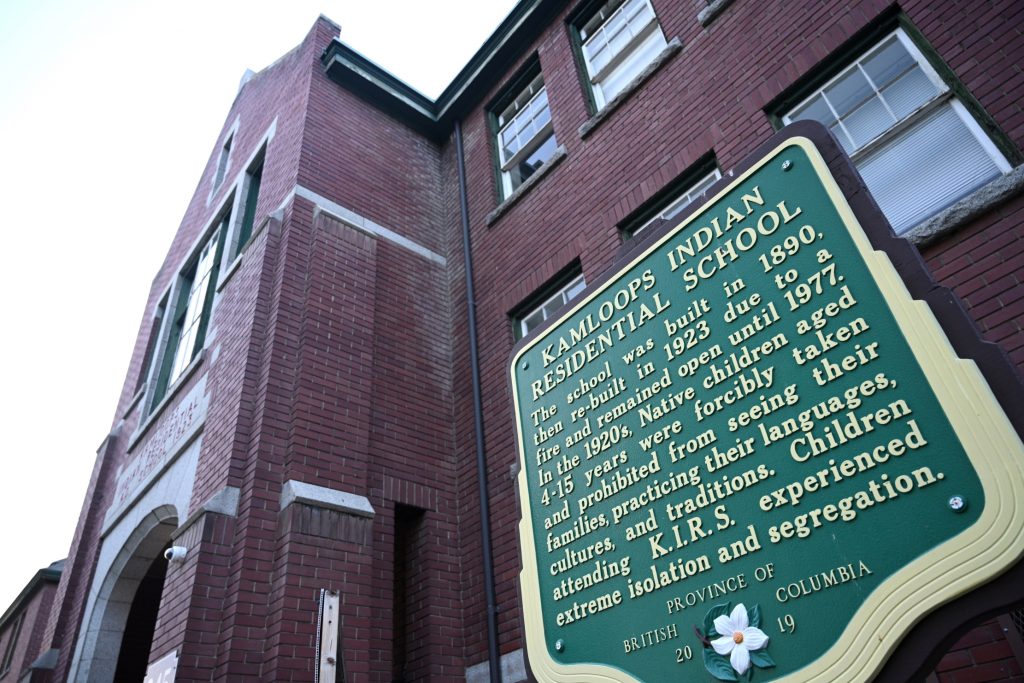

“For over 10 years, Shelley and I have been working to document the cumulative and ongoing harms of colonialism that have been inflicted on Indigenous communities over the past 500 years,” says Debra. “We have identified 15 layers of harm such as theft of resources, dislocation from ancestral lands, and residential schools, where Indigenous children were forcibly taken and stripped of their culture, language and identity after being removed from their families and communities.”

The trauma inflicted by these harms is passed from generation to generation. “If a member of these communities has turned to addiction, it is probably because they have first-hand experience of trauma or traces of trauma in their bodies from previous generations,” says Debra. “Indigenous communities have been destabilised, so to address individual challenges, we need to start by stabilising the communities – something that the Canadian Red Cross programmes support.”

For decades, the Canadian Red Cross has walked with Indigenous communities through ‘violence prevention’ programmes to support them in creating safe environments for children and youth and addressing their trauma. “However, communities started to tell us that, ‘There is a lot of information around the history of harm. We want to understand both the harms and the ways to build community wellness,’ ” says Shelley.

Flipping the narrative

“The communities were very clear with us that their journey to wellness must include the reintegration of ‘All My Relations’,” says Debra. “So, this formed the heart of our relational determinants of health model.”

Our health is affected by many factors including physical determinants, such as disease and nutrition, and social determinants, such as poverty and isolation. Indigenous Peoples are also affected by Indigenous determinants of health, such as the harms inflicted by colonialism and the resultant inter-generational trauma. “While all of these factors are important, they are really Indigenous determinants of illness,” says Debra. “As I understand it, Indigenous world-views tend to be strength-based, so our model flips the narrative from social and Indigenous determinants of health, which focus on harms and violence linked to illness, to the relational determinants of health, which focus on the culturally-grounded processes that sustain communities and help them thrive.”

The relational determinants of health

“When developing our model, we started to look at the pathways that could support communities in moving from disruption to reconnection,” says Shelley. “We thought about the relational determinants of health in relation to four dimensions of Indigenous well-being: the physical, emotional, mental and spiritual.”

Within the physical aspect, reconnecting with the land is key. “When you have been moved or pushed away from your home territory, is there a way of reconnecting to it?” asks Shelley. “If not, connecting to the space that now grounds you is vitally important. Part of this process is learning about whose territory we are currently living on and how we can be a participant in stewarding that territory. We can also think about planting traditional medicine and food plants in our own gardens to form a stronger connection with the land.”

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM654

© Bumble Dee/Shutterstock.com.

The emotional aspect includes nurturing familial relationships, building confidence and self-esteem, and learning about emotional safety. “It’s really all about connection,” says Shelley. “If we cannot reconnect to our home territory or Nation, we need to think about how we can volunteer and provide service in our local area and support the nations that live there.” These activities can help to build and maintain emotional connections with others.

“When we think about the mental aspect, we think about things like self-determination and personal agency,” continues Shelley. Self-determination plays a huge part in a community’s journey to wellness. “Indigenous communities are continuously restoring their own governance structures and cultural ways of being,” says Debra. “They may need support from other Indigenous nations, but nobody knows better than the community what they need to move toward wellness.” The mental aspect also highlights lifelong learning of Indigenous language, culture and stories as a key step towards wellness.

The spiritual aspect focuses on restoring traditional flows and ‘All My Relations’, with ceremony playing a key role. “For me, connecting with other Indigenous People and participating in ceremonies, such as sweats, is very important,” says Shelley. Sweats are spiritual ceremonies that take place in sweat lodges and often involve prayer and singing.

Looking to the future

Although Indigenous communities still experience violence and disconnection, the relational determinants of health can support them to reclaim their health and well-being. “Communities are really starting to focus more on the cultural aspects of their wellness,” says Shelley. “It’s heartening to hear communities actively talking about aspects of language, culture, land and ceremony.”

“This research-practice partnership between Indigenous communities, York University and the Canadian Red Cross is strong because we’ve taken the time to walk alongside the communities and take direction from them,” says Debra. “We’ve expanded our understanding and we know where we need to go in terms of promoting community wellness, and I think that is what’s so exciting.”

Shelley Cardinal

Shelley Cardinal

Senior Director, Office of Indigenous Relations, Canadian Red Cross

Debra Pepler

Distinguished Research Professor of Psychology, York University, Canada

Fields of research: Cultural safety, Indigenous wellness, healthy development, psychology, violence prevention

Research project: Supporting Indigenous communities’ journeys to wellness through the relational determinants of health model

Funders: Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC); British Columbia’s Crime Reduction Research Program (CRRP)

About participatory research

Participatory research involves working alongside individuals and communities and researching topics that impact them. This means that individuals and communities actively participate in the research process, collaborating with researchers and others to co-create knowledge and use this knowledge to bring about social change.

This is radically different to how research involving Indigenous Peoples has been undertaken in the past. Historically, research on Indigenous Peoples in Canada has been unethical, with researchers extracting knowledge from communities without providing any reciprocal benefit. Members of Indigenous communities were also treated as subjects rather than partners, often being harmed in the process. “University teaches you to be independent, to be the expert in the room, to be the leader, to have unique ideas,” says Debra. “Participatory research teaches you to be interdependent – if you are not Indigenous, you don’t lead, you walk alongside and listen.” On the other hand, if you are a member of an Indigenous community, it is of great value when you assert and share your knowledge. “As Indigenous community members, you are the knowledge holders of your Nation,” says Shelley.

Debra has been involved in participatory research with Indigenous communities for twenty years, in close partnership with Shelley and others. “You have to go in with humility,” she says. “You have no idea what Indigenous People need or want, or what their worldview is.” Shelley and Debra’s work has involved being guided by members of First Nations communities, Inuit hamlets, and urban Indigenous organisations to understand how to bring about positive change. “Walking alongside and learning from Indigenous colleagues and communities has been an immense privilege,” says Debra.

Critical learnings

Truth and Reconciliation

“Regardless of the work that you want to do or the career direction that you take, it’s good to have an understanding of Truth and Reconciliation,” says Shelley. Truth and Reconciliation refers to the process of restoring respectful relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples, acknowledging the harm caused by colonialism, and working towards a future where Indigenous rights are recognised and respected.

Allyship

It is important to remember that calling yourself an ally is not the same as being one. Allyship is an active process of speaking out against oppression, educating others and supporting Indigenous communities. For non-Indigenous people, it starts with listening to and learning from Indigenous communities to understand how you can best walk alongside them.

Cultural safety

Cultural safety involves creating environments in which everyone feels safe, respected and valued, no matter their cultural identity. As you move through your education and career, think about how you can help to create culturally safe spaces by addressing power imbalances, reflecting on your words and actions, and respecting other people’s values and beliefs.

Ethical spaces of engagement

When Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities work together, it is important to create ‘ethical space’. This involves creating a space where people with different worldviews can come together respectfully to work towards shared goals without the constraints of ingrained power imbalances and cultural assumptions.

Meet Shelley

When I was around 5 years old, my Kokum (grandmother in Cree) took me for a walk into the bush to collect porcupine quills. We gathered many quills that day and I learned to love the bush and what it provides us. I’ve also been a lifelong history buff, and I’m interested in the gifts that culture holds and the harms that have deeply impacted my family and community.

My friends often hear me say, “I love my job.” I’ve worked for the Red Cross for over 25 years and have had the privilege of spending time in hundreds of Indigenous communities who also want to better understand the cycles of violence affecting them. As I’ve worked alongside communities, I’ve come to understand how to integrate the stories of our harms and give them space but not power. From this place, we turn and walk towards our wellness.

I’m a curious person and a good listener. As someone who grew up weaving beads, I’ve used the art of weaving to weave information and transform it in ways that are understandable and generate solutions that I share back to community.

Meet Debra

As a youth, I found every opportunity to volunteer or work in youth-serving settings. I wanted to become a physical education teacher, but then I fell in love with research. The questions that I have asked throughout my research career have always focused on the importance of children and youths’ relationships at home, at school and in the community.

As a professor, I love working with students and supporting them along their own learning and career pathways. It is a joy to watch students become excited about child and youth development and acquire knowledge and sensitivities to begin a career working with children, youth and families.

I have learned so much about being relational from my Indigenous colleagues, friends, communities and students. It has really changed the way I walk in the world. In our partnership research with Indigenous communities, I have learned to talk little, listen deeply, be patient and know that the expertise lies within the communities. Shelley has been so important in my learning journey, and for that I am forever grateful. Hiy Hiy! (‘Thank you’ in Cree)

Do you have a question for Shelley or Debra?

Write it in the comments box below and they will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

0 Comments