How can we design social media to be inclusive?

GLOSSARY

AUTISM – a developmental difference which affects how people communicate and interact with the world

GIF (GRAPHICS INTERCHANGE FORMAT) – a short, animated image commonly used online

LINGUISTIC ETHNOGRAPHY – the interpretation of human interactions within the specific social contexts and structures in which they occur

SOCIAL MEDIA/SOCIAL NETWORKING SITES – online platforms where people can connect, communicate and share information

The coronavirus pandemic has changed some of the ways we communicate, with virtual interactions replacing many of our face-to-face conversations. While online communication has been a challenge for many, autistic people encountered barriers in communication before the pandemic.

At Queen Mary University of London, linguists Professor Nelya Koteyko and Dr Martine van Driel are investigating how autistic people interact with and through social media, and how changes in the design of digital platforms might benefit autistic users.

WHAT’S IN AN EMOJI?

“When we communicate online, we are missing a large part of in-person communication, for instance body language, eye contact and gestures,” explain Nelya and Martine. As we now live large parts of our lives in an online environment, we are having to learn how to adapt to these missing gestures. Since the advent of text messaging, we have been replacing these physical cues to our moods and feelings, first with emoticons such as :-), then emojis such as 😊 and finally with GIFs and memes on social media.

As we increasingly use these online displays of emotion, we also become more sensitive to their meanings. And it’s not just about emojis and GIFs. Punctuation can also change the tone of a non-verbal message, as can the use of capital letters. Imagine you are late to meet your friend in the park. They have already arrived and so send you a message to let you know. How would you feel receiving these three different messages?

How does their choice of punctuation change how you feel about their message? Perhaps message 1 with no punctuation is just a statement, simply letting you know that they have arrived at your meeting point. An exclamation mark generally indicates excitement, so the sender of message 2 is probably excited to see you when you arrive. But adding a full-stop to the end of a short online message? This is often considered passive aggressive or angry. If you receive message 3, take the hint that your friend is fed up with your lateness!

AND WHAT DOES THIS HAVE TO DO WITH LINGUISTICS?

Linguistics is not about speaking lots of different languages. It is about the structures and patterns of human communication, and in the case of applied linguistics, the contexts in which these structures and patterns arise.

The rise of social media provides a new area of research for applied linguists, as the contexts in which we use language to communicate online are different from face-to-face communication. As applied linguists, Nelya and Martine are interested in how people use language as well as emojis, GIFs and images to communicate and connect with others through social networking sites and digital platforms.

WHY MIGHT AUTISTIC PEOPLE PREFER ONLINE COMMUNICATION?

In the UK around 700,000 children and adults are autistic, a developmental difference which affects how people interact with others and their environment. Nelya and Martine are collaborating with the autism charity Autistica to examine how autistic adults communicate via social networking sites.

Some autistic people have different ways and preferences for using body language; for example, not relying on eye contact during conversation as much as non-autistic people do. In face-to-face interactions with non-autistic people, this may lead to misunderstandings. Social media environments come with different forms of communication, where eye contact no longer plays a central role, and where we can choose to use only text or to supplement text with still or moving images (e.g. GIFs) “In addition, communicating online means autistic people can avoid things that may be overwhelming, such as travel to physical meetings, background noise and interacting with strangers,” explains Martine.

For these reasons, some autistic people may prefer to communicate online rather than face-to-face, making social media an important environment for autistic users. However, most social media platforms have been designed by and for non-autistic users, meaning some features may still not be inclusive.

WHAT CAN TWEETS AND HASHTAGS TELL US?

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM178

AUTISM – a developmental difference which affects how people communicate and interact with the world

GIF (GRAPHICS INTERCHANGE FORMAT) – a short, animated image commonly used online

LINGUISTIC ETHNOGRAPHY – the interpretation of human interactions within the specific social contexts and structures in which they occur

SOCIAL MEDIA/SOCIAL NETWORKING SITES – online platforms where people can connect, communicate and share information

The coronavirus pandemic has changed some of the ways we communicate, with virtual interactions replacing many of our face-to-face conversations. While online communication has been a challenge for many, autistic people encountered barriers in communication before the pandemic.

At Queen Mary University of London, linguists Professor Nelya Koteyko and Dr Martine van Driel are investigating how autistic people interact with and through social media, and how changes in the design of digital platforms might benefit autistic users.

WHAT’S IN AN EMOJI?

“When we communicate online, we are missing a large part of in-person communication, for instance body language, eye contact and gestures,” explain Nelya and Martine. As we now live large parts of our lives in an online environment, we are having to learn how to adapt to these missing gestures. Since the advent of text messaging, we have been replacing these physical cues to our moods and feelings, first with emoticons such as :-), then emojis such as 😊 and finally with GIFs and memes on social media.

As we increasingly use these online displays of emotion, we also become more sensitive to their meanings. And it’s not just about emojis and GIFs. Punctuation can also change the tone of a non-verbal message, as can the use of capital letters. Imagine you are late to meet your friend in the park. They have already arrived and so send you a message to let you know. How would you feel receiving these three different messages?

How does their choice of punctuation change how you feel about their message? Perhaps message 1 with no punctuation is just a statement, simply letting you know that they have arrived at your meeting point. An exclamation mark generally indicates excitement, so the sender of message 2 is probably excited to see you when you arrive. But adding a full-stop to the end of a short online message? This is often considered passive aggressive or angry. If you receive message 3, take the hint that your friend is fed up with your lateness!

AND WHAT DOES THIS HAVE TO DO WITH LINGUISTICS?

Linguistics is not about speaking lots of different languages. It is about the structures and patterns of human communication, and in the case of applied linguistics, the contexts in which these structures and patterns arise.

The rise of social media provides a new area of research for applied linguists, as the contexts in which we use language to communicate online are different from face-to-face communication. As applied linguists, Nelya and Martine are interested in how people use language as well as emojis, GIFs and images to communicate and connect with others through social networking sites and digital platforms.

WHY MIGHT AUTISTIC PEOPLE PREFER ONLINE COMMUNICATION?

In the UK around 700,000 children and adults are autistic, a developmental difference which affects how people interact with others and their environment. Nelya and Martine are collaborating with the autism charity Autistica to examine how autistic adults communicate via social networking sites.

Some autistic people have different ways and preferences for using body language; for example, not relying on eye contact during conversation as much as non-autistic people do. In face-to-face interactions with non-autistic people, this may lead to misunderstandings. Social media environments come with different forms of communication, where eye contact no longer plays a central role, and where we can choose to use only text or to supplement text with still or moving images (e.g. GIFs) “In addition, communicating online means autistic people can avoid things that may be overwhelming, such as travel to physical meetings, background noise and interacting with strangers,” explains Martine.

For these reasons, some autistic people may prefer to communicate online rather than face-to-face, making social media an important environment for autistic users. However, most social media platforms have been designed by and for non-autistic users, meaning some features may still not be inclusive.

WHAT CAN TWEETS AND HASHTAGS TELL US?

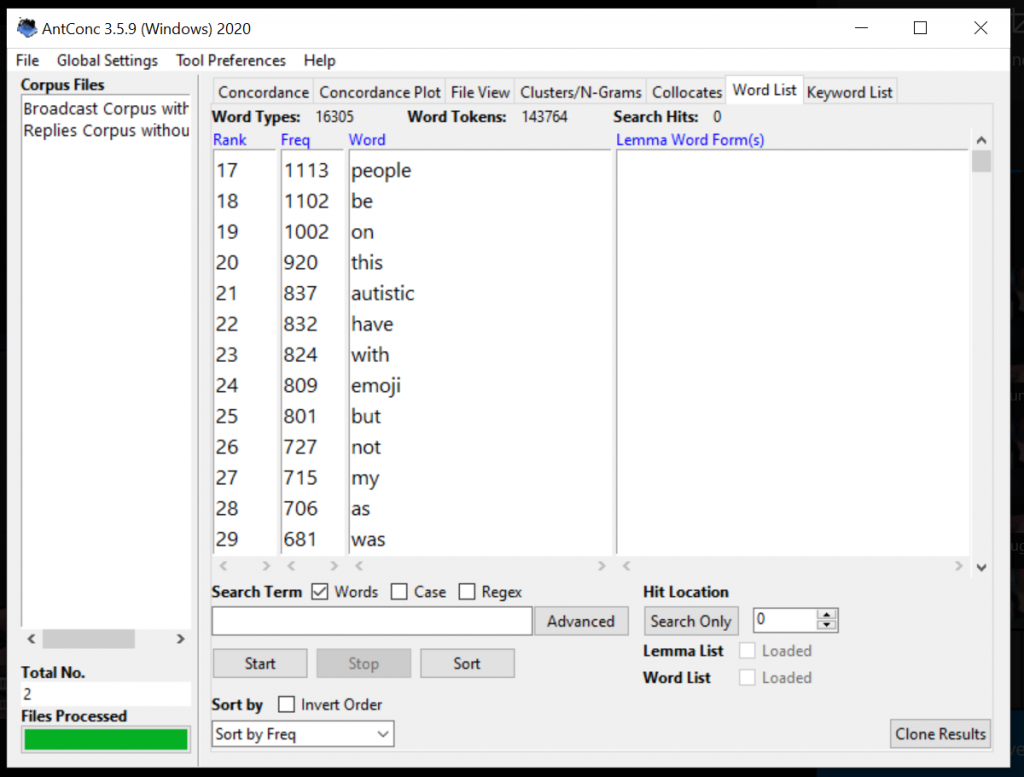

Nelya and Martine have a step-by-step plan of how to investigate this issue. First, they are observing how autistic participants interact on social media platforms by studying their posts on Facebook and Twitter. “We observe what features of the platform they use, and look for patterns in what they post and how they post it. For example, do they tag people or use hashtags?” says Nelya. “Or do participants include emojis?” adds Martine. “If so, we ask what the emojis do in each specific post. Do they clarify the emotion in the text, or do they turn the text into a joke?” Hashtags and emojis are useful for people to find others online and to relate to each other. Nelya and Martine use special linguistics software to analyse the language in the posts to see how specific words or word combinations are used, enabling them to look into patterns across the thousands of social media posts they have collected. They also note the types of social media features used, for instance ‘sharing’, ‘replying’ or posting ‘status updates’.

Next, Nelya and Martine conduct interviews with the participants, asking about their experience of using social media. They analyse interview transcripts to identify themes and topics that participants talk about when discussing their social media use. They are already starting to get some important feedback. “Autistic users of these platforms said they liked the ability to easily step away from an interaction when they need a break or need a bit more time to think about what to say,” Martine reports.

WHAT NEXT?

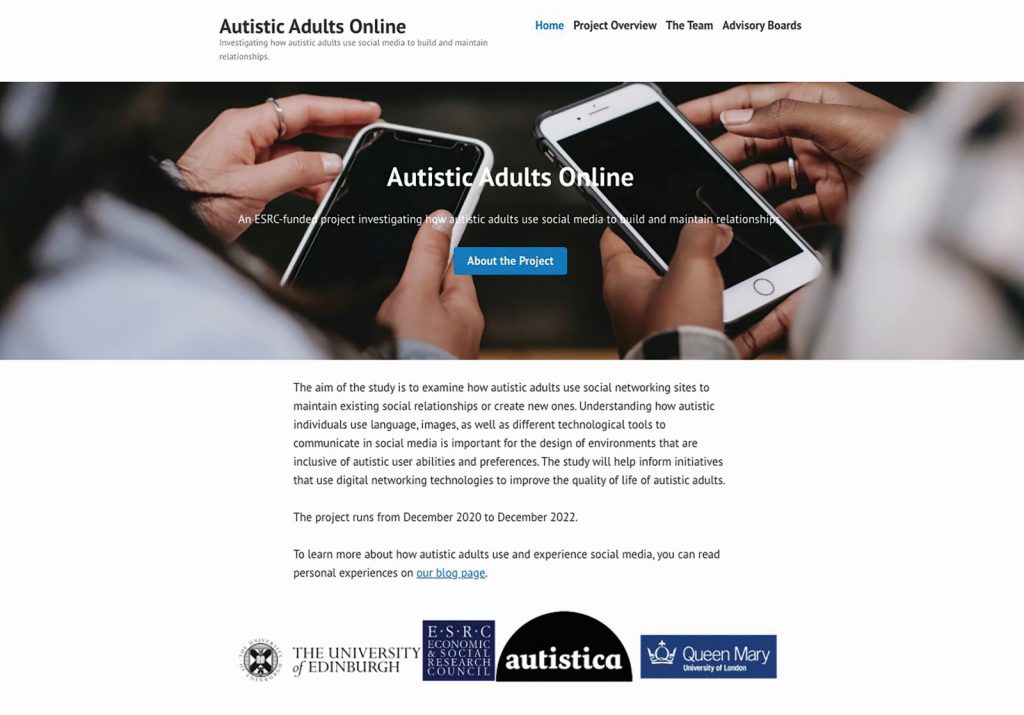

In the final part of the plan, Nelya and Martine will be working with Professor John Vines at the University of Edinburgh and autistic social media users to put their knowledge into practice. John is interested in how people interact with computers and uses this knowledge to improve software design. “Once we understand how autistic people use language, images and technical features such as ‘likes’ on social media platforms, this knowledge can be used by software designers to create digital networking environments that take autistic user preferences into account,” explains Nelya.

Nelya and Martine emphasise that their project is not about imposing solutions from academic theory. “It is crucial to work with autistic participants directly so we can learn from their experiences and understand why they use social media in the ways that they do.” If you have a passion for inclusion and a curiosity about language, a career in applied linguistics could be for you!

PROFESSOR NELYA KOTEYKO

PROFESSOR NELYA KOTEYKO

Professor of Language and Communication,

Queen Mary University of London, UK

DR MARTINE VAN DRIEL

Postdoctoral researcher in Applied Linguistics,

Queen Mary University of London, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Applied Linguistics

RESEARCH PROJECT: Analysing autistic user experiences of online social networking and improving social networking platforms

PROJECT WEBSITE: www.autisticadultsonline.com

PROJECT TWITTER PAGE: www.twitter.com/Online_Autistic

ABOUT LINGUISTICS

As the study of language and communication, linguistics is a broad field covering many subdisciplines. Applied linguistics is often concerned with how language is used in the everyday, by individuals or specific groups and institutions. “When we look at patterns in language, we can aim to examine why some word choices seem to be more successful than others at conveying particular meanings in specific contexts, while others may result in misunderstanding,” says Nelya.

Martine sees linguistics as playing an important role in our culture and society. “We can draw attention to all the different ways people communicate, with the hope that everyone will become more aware of the diversity that we have,” she explains. “The most challenging aspect is that we can never know how someone intended their words or text to be understood.”

HOW CAN LINGUISTICS HELP WITH PUBLIC HEALTH COMMUNICATION?

“How patients, doctors or political leaders talk face-to-face or online can tell us about how people experience and understand particular illnesses, as well as their treatment and prevention,” explains Nelya. Since the start of the pandemic, we have all been overwhelmed by media statements and press conferences, and the value of science communication has become more obvious than ever. Nelya is passionate about using linguistic analysis to understand how knowledge about health and illness is communicated by different groups in society, and how people talk about their experiences of living with illness.

WHAT ISSUES WILL BE FACING THE NEXT GENERATION OF LINGUISTS?

“The current objects of applied linguistics research still often come from Anglo-American or European cultures,” says Nelya. “This means that ‘real world’ issues tend to be limited to mostly Western, affluent societies.” However, she is optimistic that this is starting to change, particularly in the field of linguistic ethnography. “There is a growing interest in how we talk and write about issues such as inequality, war and climate change in a variety of cultures and societies.”

Although Martine spends much of her time researching online communication, she still believes that “as the ways we communicate continue to evolve, it will be important to remember that often we can connect how we communicate online to how we speak in-person”.

EXPLORE A CAREER IN APPLIED LINGUISTICS

• With a background in linguistics, you could explore academic roles in research or teaching, medical roles such as speech therapy, or use your skills for a broader range of media-focused careers.

• Keep up to date with linguistics research by reading magazines and listening to podcasts. Nelya recommends:

• Babel: babelzine.co.uk

• ULAB: www.ulab.org.uk/about-ulab

• Lingthusiasm: www.lingthusiasm.com

• BBC Word of Mouth: www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b006qtnz

• En Clair (using linguistics to solve crime!): wp.lancs.ac.uk/enclair

• Visit the British Association of Applied Linguistics (www.baal.org.uk) or the International Association of Applied Linguistics (www.aila.info) to learn more about the field.

• Learn about the importance of linguistics for health and science communication and find out about upcoming talks and events: baalhealthsci.wordpress.com

• Find out about linguistics and language events for schools run by Queen Mary University of London: www.qmul.ac.uk/sllf/outreach

PATHWAY FROM SCHOOL TO APPLIED LINGUISTICS

“Try to take courses that teach you about grammar (in any language),” advise Nelya and Martine, “as well as courses where you will learn about different people and cultures, such as sociology and anthropology.”

Many universities will offer linguistics degrees. You will be able to specialise in applied linguistics as you progress through your studies.

HOW DID NELYA BECOME A LINGUIST?

I initially wanted to become a botanist, keen to classify plant species. But in the final years of school I turned my attention to patterns and classifications in language – first in translation and later becoming interested in English on its own.

I found myself really enjoying writing a linguistics dissertation for my undergraduate degree, having expected it to be more like completing a final chore. Working ‘with’ a research supervisor rather than simply listening to lectures was a big part of that. Collaborative and interdisciplinary research is still important to me now.

I have not followed any well-defined plan to become a linguist. I have previously worked in departments of sociology and media studies, although linguistic analysis has always been key to my research.

Immigrating to the UK as a young adult has sharpened my interest in how meaning is communicated and negotiated across difference, whether it is between different cultural groups using the same language or between people who have different communicative abilities and preferences. I am proud to have contributed to the development of linguistic tools that help us examine and understand such communication.

Technology (such as mobile phones) is now firmly part of our everyday lives. I strive to highlight the important contributions linguists can make to multidisciplinary projects that want to understand the role of communication technology in ‘big’ societal questions about inclusion and/or health and well-being.

Out of work I enjoy playing volleyball, although in the last five years it is more about playing with my young daughter!

HOW DID MARTINE BECOME A LINGUIST?

I was always a big reader when I was younger, mainly reading fiction. When I went to university, I discovered my interest in language, both through extracurricular activities like debating and through classes in linguistics.

I’ve always been curious – I would ask a lot of questions as a child! When it comes to language, I think it is fascinating how much the way we say something can affect what people think about us, the topic, and the world at large.

Finding a job during a global pandemic is something I am very proud of as very few universities were hiring so competition was fierce. I also have a book contract for a personal research project of mine, which is amazing.

I’m hoping that in a few years I will be able to move to a permanent lectureship, where I would get to teach and do research.

In my free time, I love to swim, it really clears my mind. I also have a dog called Pippa who I like to take on walks or just cuddle with. I also love reality TV shows! Sometimes your mind needs a little break after a day of deep thinking.

NELYA AND MARTINE’S TOP TIPS

01 Try to figure out what interests you most, whilst also remaining open to the different opportunities that life can offer you.

02 Do not be afraid to contact academic researchers about their work – they will be excited to hear that someone is interested, and happy to give their advice!

03 When you receive criticism on your work you should read it through once, but then take some time to ‘cool off’ before responding. This will help you to be more objective and learn from the criticism – which is what criticism is all about!

Do you have a question for Nelya or Martine?

Write it in the comments box below and Nelya or Martine will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)