A crisis of clarity: can defining biodiversity help us protect the natural world?

For centuries, many humans have treated nature as a commodity, purging forests of trees and the oceans of fish. As a result, biodiversity in ecosystems around the world is declining at an alarming rate, threatening the balance of life on earth. But what is biodiversity, and how can we measure it? Professor Charles Pence from the Université catholique de Louvain in Belgium believes that answering this question is of vital importance if we are to stop the looming biodiversity crisis

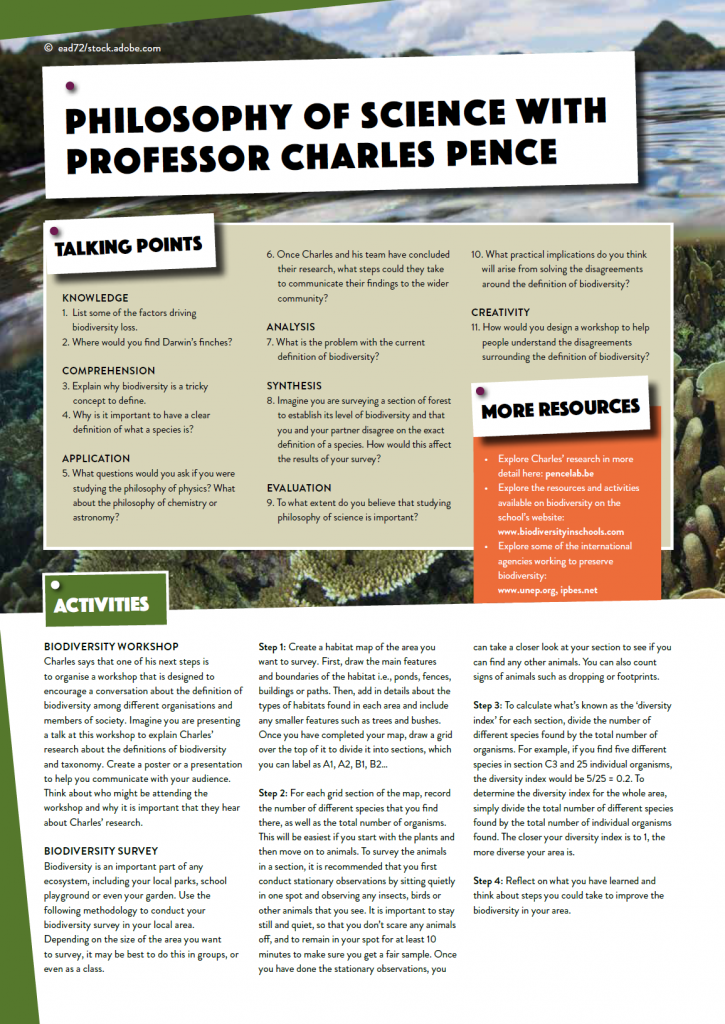

TALK LIKE A PHILOSOPHER OF SCIENCE

BIODIVERSITY – the variety of life found within an ecosystem or, more generally, on Earth

SPECIES – the basic unit we use to classify organisms, often defined as similar individuals that are capable of interbreeding

TAXONOMY – the branch of science associated with classifying and organising organisms

INTERDISCIPLINARITY – the collaboration of two or more branches of knowledge

ECOSYSTEM – all the organisms in a place and the environment that they interact with

CONCEPTUAL ENGINEERING – a method philosophers use to try to find and fix places where ideas from science (or everyday life) are confused or unclear

Around the world, biodiversity is decreasing at an alarming rate. In Brazil, vast swathes of the Amazon rainforest are being decimated and transformed into farmland. In the eastern Pacific, rising sea temperatures are causing massive bleaching events on coral reefs, leaving these once vibrant ecosystems barren and lifeless. And in the UK, invasive plant species like rhododendron and Himalayan balsam are crowding out native trees and causing a massive reduction in biodiversity.

This loss of biodiversity has the potential to become one of the biggest threats facing humanity over the coming decades. Biodiversity forms the foundation of all healthy ecosystems on the planet. As more species are threatened by climate change, habitat loss and invasive species, these ecosystems could become irreparably damaged.

We rely on many of these ecosystems for the services that they provide. For example, healthy forests can reduce air pollution, prevent flooding and soil erosion, absorb carbon from the atmosphere and provide humans with places to relax and explore. Without the biodiversity that underlies them, we would not have forests and all that they provide for us.

WHAT IS BIODIVERSITY AND HOW CAN WE MEASURE IT?

These questions, it turns out, are harder to answer than they would first appear. Their answers are shrouded in debate and uncertainty, making it hard for scientists to collaborate on potential solutions to the biodiversity crisis. Professor Charles Pence from the Université catholique de Louvain is leading a research project that aims to clarify these definitions. Without precise definitions, Charles argues, we will struggle to understand the impacts that we are having on biodiversity and how we might be able to protect it.

Biodiversity is commonly defined as the total number and variety of species found within an ecosystem. On paper, this seems like a fairly simple and concise explanation. However, when scientists try to apply it to nature in the real world, things become less clear. Charles explains that one problem with this definition is that “there’s also very little agreement about how to define species.”

In nature, boundaries between different species, habitats and ecosystems are often blurred. For example, a species is often defined as a group of organisms that can breed and produce fertile offspring. Lions and tigers are not the same species because when they mate, their offspring, known as ligers, are sterile and not able to reproduce.

Although many scientists accept this definition, “others,” Charles points out, “may point to different kinds of visible (morphological) characteristics, arguing that species need to have similar traits.” Darwin’s finches, for example, found on the Galapagos Islands, are often considered to be many different species based on variations in their morphology and behaviour. Despite this, there have been many reports of interbreeding between members of the supposedly distinct species.

WHY IS CLARIFYING THESE DEFINITIONS IMPORTANT?

The debate around how to define a species has a significant effect on how scientists understand and measure biodiversity. “If we take a population and split it into a larger number of species,” explains Charles, “those species may immediately be more endangered without any change in the natural world.”

The ecosystem that these species are a part of would also appear to have a higher level of biodiversity than it does. This can significantly change how healthy an ecosystem appears and can lead to vulnerable populations being overlooked. “All that just because we changed our opinion about what counts as a species,” says Charles.

Clarifying these issues will have benefits not only for the scientific community but also for many other members of society who are trying to protect biodiversity. “We often get wide agreement from business leaders, NGOs, governments and more that biodiversity is something that needs to be saved,” says Charles. Uncertainty around the exact definition of biodiversity may make it harder for these groups to collaborate and work together.

Charles asks, “Is this disagreement part of the reason that we’ve failed to protect biodiversity in the past?” He believes that finding a more concrete and widely accepted definition could help us avoid miscommunication and create a more coherent strategy for protecting biodiversity.

HOW IS THIS PROBLEM STUDIED?

Much of Charles’ research is focused on understanding the disagreements that surround the concept of biodiversity. Charles and his team use complex digital tools to analyse huge collections of research articles on biodiversity and taxonomy to identify where, when and by whom different definitions are used. Mapping out these discrepancies and identifying trends in how the different definitions are used will enable Charles and his team to understand where clarification is needed.

Another aspect of Charles’ research involves examining science in a historical context. In particular, Charles says that he is “hoping to explore the development of the idea of biodiversity – a word that was only invented in the 1990s! – as a way to understand what non-scientists mean by the term.” Understanding how and why the concept of biodiversity was first coined will allow Charles to make sense of how different groups of society use the term.

“In the kind of work that we do, interdisciplinarity is essential,” says Charles. His work sees him collaborating with linguists and scholars in the field of digital humanities, researchers of the history and sociology of science and biologists, taxonomists and ecologists that study biodiversity. Charles explains, “Interdisciplinary work is, I think, the only way that we can meet the kinds of grand challenges that we face today!”

Despite the benefits, interdisciplinary work still poses a challenge for Charles. Researchers are very busy people and finding mutually agreed free time can be difficult. This is particularly challenging for Charles as his research may be considered by some to be a “pie in the sky” project. This means that although other researchers may find the problem interesting, they may struggle to see how it will translate into practical outcomes.

WHAT IS NEXT FOR THE RESEARCH?

Charles believes that the concept of biodiversity was never intended to be restricted to the scientific community. “We invented the word,” Charles says, “not only because we had scientific goals that we wanted to pursue, but because we wanted to change the world to better protect the species around us.” Many different people from all over the world want to do their bit to protect biodiversity, and Charles and his team are running workshops to bring all of these people together to help them collaborate.

Charles hopes that these workshops, along with his research, will help to resolve many of the disagreements surrounding the definition of biodiversity. “A natural second step is to think about what we might do about it – how can we use this knowledge to make the world a better place,” he explains.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM282

Charles’ research group, with collaborators from Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (KU Leuven) and Hasselt University (UHasselt) in Belgium, 2021.

Presenting work on digital humanities in Aarhus, Denmark, 2019. © Samuel Schindler.

Lecturing at the EMBL Graduate Conference, Heidelberg, 2019. © Elisa Kreibich/EMBL.

Finishing the Maas Marathon, 2021. © Sportograf.

Charles’s two most recent books.

Exploring glacial biodiversity on the Mendenhall Glacier, Alaska, 2016.

PROFESSOR CHARLES PENCE

PROFESSOR CHARLES PENCE

Chargé De Cours

Faculty of Philosophy, Arts and Letters

Institut supérieur de philosophie

Université catholique de Louvain, Belgium

FIELD OF RESEARCH: History and Philosophy of Biology

RESEARCH PROJECT: Exploring the debate and uncertainty surrounding the concepts of biodiversity and taxonomy

FUNDERS: FNRS (Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique, Belgium)

This work was supported by the FNRS under grant no. T.0177.21

ABOUT PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE

The philosophy of science is a field of philosophy that contemplates the foundations, methods and purpose of scientific study. “I often like to say that philosophers of science spend their time thinking about questions about science that scientists are too busy doing their jobs to have time to think about!”

Philosophers of science ask questions such as: Can science reveal the ultimate truth? How much evidence is needed to confirm a scientific theory? Does science have any moral obligations? Many of these questions have been subject to debate for centuries, and such debates will likely continue for many years to come.

They are important questions to contemplate as emergent philosophical insights can provide unique perspectives on the scientific process. Charles focuses on the philosophy of one specific branch of science: biology. The philosophy of biology contemplates questions surrounding evolution, genetics, life and, more recently, humanity’s impact on the natural world. Charles’ investigations around the concepts of biodiversity and taxonomy may help to heal humanity’s relationship with the natural world.

WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A SCIENTIST AND A PHILOSOPHER OF SCIENCE?

Scientists spend a lot of their time out in the field collecting data or in labs doing experiments to answer questions about the world around us. Philosophers of science, however, are asking questions about what scientists are doing, and why they are doing it. “What makes our work rewarding,” says Charles, “is that we have that ability to step back and think clearly about what’s going on in the sciences, without having the pressure to do more experiments or get published in high-profile science journals.”

WHAT OPPORTUNITIES WILL BE OPEN TO THE NEXT GENERATION OF PHILOSOPHERS OF SCIENCE?

One of the biggest challenges that philosophers face is translating their observations and insights into practical outcomes. “We don’t just want to do philosophy for the sake of doing philosophy,” says Charles. “We want to do it to try to better understand real problems and improve the state of the world.”

Communicating their insights to real-world decision-makers, like politicians and businesses, is not always easy for philosophers. “But it’s exactly what we need to try to do in the years to come if we hope for our research to have any real impact,” says Charles. As the biodiversity crisis deteriorates over the coming decades, this will become an increasingly important challenge for Charles’ successors to overcome.

EXPLORE A CAREER IN PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE

• There are some great public philosophy resources on YouTube such as Philosophy Tube, Jeff Kaplan and Gregory Sadler.

• The American Philosophical Association and the British Philosophical Association have some great resources for exploring a career in philosophy.

• The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy is a comprehensive and accessible research tool for learning more about philosophy.

• Questions: Philosophy for Young People is a peer-reviewed journal made up of articles written by high-school students, as well as scholars and teachers.

PATHWAY FROM SCHOOL TO PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE

• Studying history and philosophy alongside science subjects is important. Charles points out that, if history and philosophy are not available to students, studying language and literature is also beneficial.

• When studying science subjects, think about your work from the perspective of a philosopher, as well as a scientist. “Think about your study of science not just from the perspective of learning facts and figures, but asking questions about the scientific process itself,” says Charles.

• Ask questions about science when you are studying history and other subjects. Think about how science is related to history and culture, for example. Thinking about science from different perspectives is key. Charles recommends that students motivate themselves to find new ways of thinking about science and to stay curious and ask questions.

CHARLES BECOME A PHILOSOPHER OF SCIENCE?

WHAT WERE YOUR INTERESTS WHEN YOU WERE GROWING UP?

I’d always wanted to be a scientist – I went through phases when I was sure I’d be a palaeontologist, an archaeologist, a physicist or a biologist. I’ve always been excited by scientific knowledge. What changed was when I realised that the kinds of questions about the sciences that I wanted to ask weren’t those that were asked in the sciences themselves – that’s when I discovered the philosophy of science!

WHO OR WHAT INSPIRED YOU TO BECOME A PHILOSOPHER?

I was pursuing an undergraduate degree in physics, and steadily becoming disenchanted with what I was working on; spending all my days solving complex calculus problems wasn’t what I thought I would be doing when I signed up to be a scientist. At the same time, I met a professor in our philosophy department who was working on the philosophy of physics – studying the nature of quantum mechanics and reality, technically informed and extremely astute but focused on exactly the kinds of big-picture questions that I wanted to study. I was hooked.

WHAT ATTRIBUTES HAVE MADE YOU SUCCESSFUL AS A PHILOSOPHER?

I think this work requires a lot of flexibility. Some days, I might spend all day reading historical works from 19th-century biologists. Other days, I may read contemporary evolutionary theory papers or attend scientific conferences. I may also write code to run digital analyses or manage our data, servers or computing infrastructure. I love the constant variety, but I think it takes a particular kind of person.

HOW DO YOU DEAL WITH CHALLENGES YOU ENCOUNTER AT WORK?

I’m lucky to have quite an extensive network of colleagues, in a variety of different fields, all around the world. That’s my favourite part of academia; if I’m stuck or a student comes to me with a great question that I have no idea how to answer, I know where to go to get help!

WHAT ARE YOUR PROUDEST CAREER ACHIEVEMENTS SO FAR?

This year, I’ve published two books that were long in the making: one on the history of biology, chronicling the development of statistics and chance in evolutionary theory, and another on contemporary philosophical work on the structure of natural selection. I think they’re some of my best work, and I’m just thankful that I’m in a position where I get to do this every day.

WHAT DO YOU DO TO UNWIND?

When I’m not working, I’m usually out for a long run, listening to music or playing video games.

CHARLES’ TOP TIPS

01. Stay curious and ask lots of questions.

02. Think about science from as many different perspectives as you can.

03. Don’t feel that you’re being a bad scientist for asking different types of questions.

Do you have a question for Charles?

Write it in the comments box below and Charles will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)