A working class hero is something to be

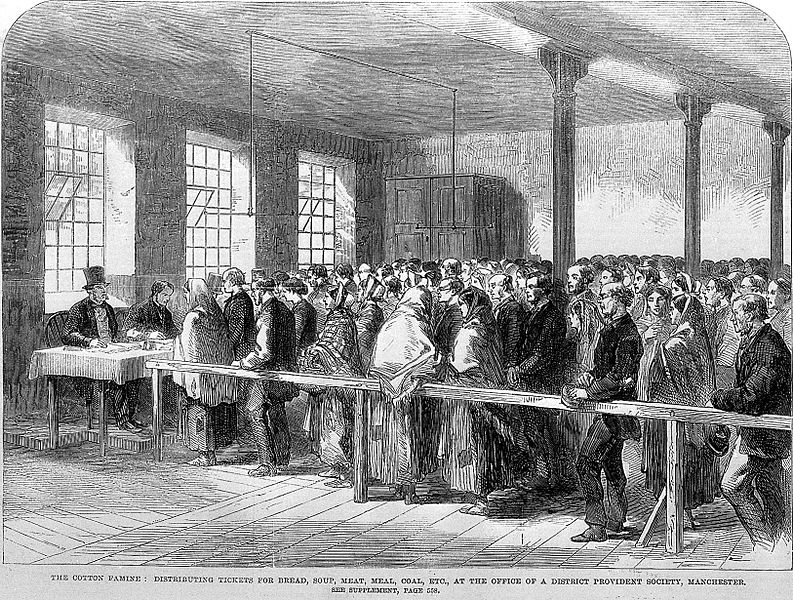

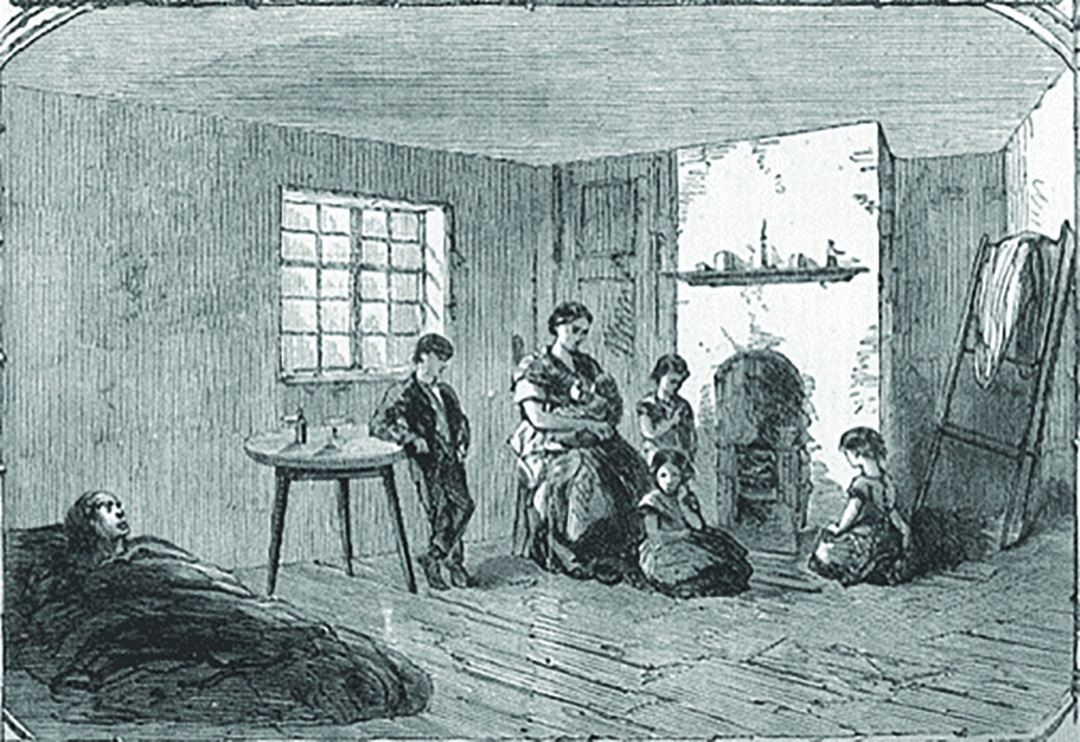

Although people in the North of England mostly opposed slavery, they suffered terribly when their factories ran out of cotton. Many families experienced hunger and malnutrition as the work dried up, and it was some time before adequate charity and relief efforts kicked in and their suffering was alleviated. It is estimated that the Cotton Famine affected almost 20% of the UK population.

Now Dr Simon Rennie, based at the University of Exeter, is working to uncover the poetry of the Lancashire Cotton Famine, and in doing so, making many working-class voices from the period heard for the very first time.

WHAT IS THE POETRY OF THE LANCASHIRE COTTON FAMINE?

During the Lancashire Cotton Famine, thousands of poems were written. Many of these poems were written by working-class people, who used poetry as a medium through which they could document their thoughts and feelings regarding political and social events of the day.

Simon’s interest in the poems came about because nobody had ever written about them before. “My previous research had been into poetry of the Chartist period, which was the generation before (1838-1848), so I already had a strong interest in working-class poetry of the Victorian era,” explains Simon. “The idea that nobody had read these poems before excited me; searching for unread poems is like digging for treasure.”

In the course of his research, Simon has come to realise that the works can tell us interesting things about the historical context of the Lancashire Cotton Famine.

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO INCREASE PUBLIC KNOWLEDGE OF THE LANCASHIRE COTTON FAMINE?

Although things are improving now, there has not been anywhere near enough attention paid to working-class literary production in the nineteenth century, and this means that things like the Lancashire Cotton Famine are only understood from incomplete sources. If we can understand what ordinary people thought about the famine through their poetry, then we gain a broader, deeper historical view of its effects.

There is a lot of talk now about the global economy, but this is an early example of a failure of global capitalism. Countries have relied on each other for their financial wellbeing for centuries. This is a global event that deeply affected almost a fifth of the population of the UK, but many people, even quite well-educated people, have barely heard of it.

HOW WERE THE POEMS ‘RE-FOUND’ AFTER ~150 YEARS?

It is sometimes not recognised that by far the largest publishers of poetry in the nineteenth century was the network of local newspapers. In Lancashire, which had a very high population density because of the Industrial Revolution, almost every town had two newspapers, and they would usually publish at least one poem every week. When you add all these together there are thousands of poems, and many of them discuss current affairs or their concerns.

“The British Library holds some of these newspapers in digital or hard copy form, but so do local libraries, often as microfilm versions. Because poems look different on the page to prose articles, they are easy to spot,” says Simon. “It is simply a matter of reading them and working out their subject matter.”

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO UNCOVER THESE PREVIOUSLY HIDDEN VOICES?

The voices contained within the poems tell us something about the times in which they were written and provide a fascinating insight into what ordinary people felt and thought. One of the most exciting aspects of Simon’s research is that there are bound to be countless other areas of research that can uncover voices that are currently lying dormant. The voices are there – you just need to find them.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM11

Although people in the North of England mostly opposed slavery, they suffered terribly when their factories ran out of cotton. Many families experienced hunger and malnutrition as the work dried up, and it was some time before adequate charity and relief efforts kicked in and their suffering was alleviated. It is estimated that the Cotton Famine affected almost 20% of the UK population.

Now Dr Simon Rennie, based at the University of Exeter, is working to uncover the poetry of the Lancashire Cotton Famine, and in doing so, making many working-class voices from the period heard for the very first time.

WHAT IS THE POETRY OF THE LANCASHIRE COTTON FAMINE?

During the Lancashire Cotton Famine, thousands of poems were written. Many of these poems were written by working-class people, who used poetry as a medium through which they could document their thoughts and feelings regarding political and social events of the day.

Simon’s interest in the poems came about because nobody had ever written about them before. “My previous research had been into poetry of the Chartist period, which was the generation before (1838-1848), so I already had a strong interest in working-class poetry of the Victorian era,” explains Simon. “The idea that nobody had read these poems before excited me; searching for unread poems is like digging for treasure.”

In the course of his research, Simon has come to realise that the works can tell us interesting things about the historical context of the Lancashire Cotton Famine.

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO INCREASE PUBLIC KNOWLEDGE OF THE LANCASHIRE COTTON FAMINE?

Although things are improving now, there has not been anywhere near enough attention paid to working-class literary production in the nineteenth century, and this means that things like the Lancashire Cotton Famine are only understood from incomplete sources. If we can understand what ordinary people thought about the famine through their poetry, then we gain a broader, deeper historical view of its effects.

There is a lot of talk now about the global economy, but this is an early example of a failure of global capitalism. Countries have relied on each other for their financial wellbeing for centuries. This is a global event that deeply affected almost a fifth of the population of the UK, but many people, even quite well-educated people, have barely heard of it.

HOW WERE THE POEMS ‘RE-FOUND’ AFTER ~150 YEARS?

It is sometimes not recognised that by far the largest publishers of poetry in the nineteenth century was the network of local newspapers. In Lancashire, which had a very high population density because of the Industrial Revolution, almost every town had two newspapers, and they would usually publish at least one poem

every week. When you add all these together there are thousands of poems, and many of them discuss current affairs or their concerns.

“The British Library holds some of these newspapers in digital or hard copy form, but so do local libraries, often as microfilm versions. Because poems look different on the page to prose articles, they are easy to spot,” says Simon. “It is simply a matter of reading them and working out their subject matter.”

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO UNCOVER THESE PREVIOUSLY HIDDEN VOICES?

The voices contained within the poems tell us something about the times in which they were written and provide a fascinating insight into what ordinary people felt and thought. One of the most exciting aspects of Simon’s research is that there are bound to be countless other areas of research that can uncover voices that are currently lying dormant. The voices are there – you just need to find them.

Dr Simon Rennie’s research has uncovered around 700 poems from the Lancashire Cotton Famine. There are obviously many highlights, given the huge number of poems in the collection, but Simon’s personal favourite is a dialect poem from Burnley called ‘Settling th’War’ by Williffe Cunliam (really a blacksmith called William Cunliffe).

It describes the bigwigs of a Lancashire town (‘chaps wi’ noddles full o’ larning’) discussing the American Civil War as though they could have any effect on it. It’s funny because it ridicules the situation, but also poignant because it highlights the helplessness people felt in the region as their hardship was caused by events thousands of miles away.

You can look at 100 of the poems now and keep an eye out for the later inclusion of the next 600 by visiting the Poetry of the Lancashire Cotton Famine webpage.

DR SIMON RENNIE

DR SIMON RENNIESenior Lecturer University of Exeter, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Victorian Poetry

RESEARCH PROJECT: Simon’s work focuses on poetry from the Lancashire Cotton Famine – texts which have lain dormant for over a century. The project looks at social class, because many of the poems represent working-class voices reacting to a major economic crisis – voices that are being heard for the very first time. As well as recovering a hidden history, Simon is making these voices available to the general public.

FUNDER: Arts and Humanities Research Council

DR SIMON RENNIE

DR SIMON RENNIE

Senior Lecturer, University of Exeter, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Victorian Poetry

RESEARCH PROJECT: Simon’s work focuses on poetry from the Lancashire Cotton Famine – texts which have lain dormant for over a century. The project looks at social class, because many of the poems represent working-class voices reacting to a major economic crisis – voices that are being heard for the very first time. As well as recovering a hidden history, Simon is making these voices available to the general public.

FUNDER: Arts and Humanities Research Council

ABOUT VICTORIAN POETRY

Victorian poetry is poetry that was written in England during the reign of Queen Victoria (1837-1901). While poets such as William Blake and John Clare are well known, not many nineteenth century working-class poets have been given the attention they clearly deserve. There were very many working-class poets who wrote fine poems during the Victorian era, but they were often not published in books or collections, or celebrated in their own lifetimes.

WHAT CAN STUDYING WORKING CLASS VICTORIAN POETRY SHOW US?

Working-class Victorians were more literate and literary than many people imagine, and their poetry is often revealing of their attitudes towards what was going on socially or politically. They wrote poetry because poems can be written quite quickly, and they had little time for anything else. Because working people had very few alternative ways for recording their thoughts, working-class Victorian poetry gives us a unique insight. When reading it, it can feel like someone has taken a microphone back into the past and listened in on the conversations of long-dead, ordinary people. By listening to these voices from the past, society can learn that future challenges often have echoes in history, and these can play a part in informing the decisions we make in response to them.

WHY SHOULD YOUNG PEOPLE STUDY ENGLISH AND POETRY?

Literature is humanity listening to itself. If human beings do not hear what a range of other human beings have to say, then they do not have the kind of full understanding necessary to make fully informed decisions about the way forward in society. The study of English literature at degree level teaches critical thinking – the ability to evaluate any given situation in a more rounded and complete way. Poetry condenses complex thought and feeling, which can be very useful for quickly conveying ideas. It also ‘defamiliarises’ – makes ordinary things seem strange. This is a really important way of helping people to constantly reassess the world around us. It stops us becoming complacent.

HOW CAN WE ENCOURAGE MORE MEN TO STUDY ENGLISH?

English is a female-dominated area of undergraduate study research, and there have been various studies on this and various suggestions as to how to address it. One suggestion is to increase the amount of ‘male-centred’ texts on syllabuses. But perhaps this gendering of texts is what might need to be challenged in the first place? Good male and female novelists create complex male and female characters, and poetry also is capable of speaking to a broad variety of the population.

WHAT CAREER OPPORTUNITIES ARE AVAILABLE WITH AN ENGLISH DEGREE?

Any career path that requires communication, written or verbal, is enhanced with a good literary education. Many of the most influential people in the worlds of politics, business, law and education began their careers with an English degree. Simon frequently writes references for former students who enter into all sorts of professions, because an English degree is one of the most flexible bases for higher learning. An increasingly diverse economy, with more emphasis placed on cultural capital rather than manufacturing, requires a highly educated, flexibly skilled population.

- An English degree is one of the most transferable degrees you can study, where the skills you gain are useful in most job sectors

- The English Association has loads of information on the English language and its literatures, with an aim to foster good practice in the teaching and learning at all levels

- Times Higher Education has an entire section of its site dedicated to explaining what you can do with an English literature degree

ASK DR SIMON RENNIE

WHO OR WHAT INSPIRED YOU TO STUDY ENGLISH AT UNIVERSITY?

I had always been a big reader, but for various reasons I didn’t achieve anything at school or sixth-form college. When I was in my late thirties, I was lucky enough to meet someone who inspired me to get into university, and with her encouragement and support I managed to stick with the subject through three separate degrees and to end up teaching and researching it.

DID YOU ENJOY WRITING POETRY AS A CHILD?

I did, but I’m not sure how good it was. I honestly think that the more poetry one reads, the more chance one has of writing good poetry. When I think back, I did not read nearly enough poetry. The way poetry is taught at schools now is much better than when I was younger, and so young poets produce better work. I am constantly surprised by the very high quality of poetry that young people such as my students at the University of Exeter produce.

HAVE YOU ALWAYS WORKED IN ACADEMIA?

I worked in factories and warehouses in Manchester for twenty years before I ever set foot inside a university, and I never dreamed that I would ever get the opportunity to do what I do now. Although I was clearly quite clever – and well-read – I had no real intellectual ambition until I met someone who believed in me. This should be a lesson to anyone, I think, that many people are capable of achieving what they have never even considered possible.

WHAT HURDLES HAVE YOU HAD TO OVERCOME IN THE COURSE OF YOUR CAREER?

I thought that my industrial background and my accent – which is quite unusual in this line of work – would be hurdles, but they honestly have not been. In academia, if you produce results, people do not care where you have come from. Whether it is research or teaching, often it is something of an advantage to be a little out of the ordinary.

FINALLY, IS THERE ANYTHING YOU WISH YOU HAD KNOWN WHEN YOU WERE STARTING OUT ON YOUR CAREER PATH?

I was pleased to get the opportunity to teach and to carry out research, but I hadn’t fully appreciated that the element of my job that involves helping young people through sometimes challenging times in their lives would also be so rewarding. Or that I would feel such a sense of shared kinship with my academic colleagues. Universities are like little towns or big families, and it has been an unexpected pleasure to feel that we are often all pulling in the same direction and helping each other out when need be.

SIMON’S TOP TIPS FOR STUDENTS

- To write good poetry, you must read as much poetry as possible. If you’re a budding poet, devour as much as you can!

- Many people can achieve things they never thought possible, so open your mind to possibilities and you never know what might happen.

- There are bound to be other areas of research that can rediscover what ordinary people thought about historical events. Who knows, perhaps you could be the one to uncover them

Simon has been working with a traditional music group called Faustus, who have adapted some of the working-class Victorian poems from his collection and put them to music in an album called ‘Cotton Lords’.

“The link between poetry and song was much closer in the Victorian period than it is today.” explains Simon. “Some of the poems were intended to be sung, and some even suggested the tune they should be sung to.”

You can listen to ‘Food or Work’ sung by Faustus.

Lovely read and inspiring story. Finding ways to make poetry relevant to youth and not just a must do for school is great news. Where did you find the hidden poems?

Hi Lyndsey,

Really pleased you found the article interesting. We found most of the poems in local libraries in microfilm copies of Victorian local newspapers. Occasionally these newspapers are held at the British Library too. It is a painstaking process sifting through every page of every local newspaper in every Lancashire town, as you can imagine. But it has been very rewarding.

Best wishes,

Dr Simon Rennie, University of Exeter