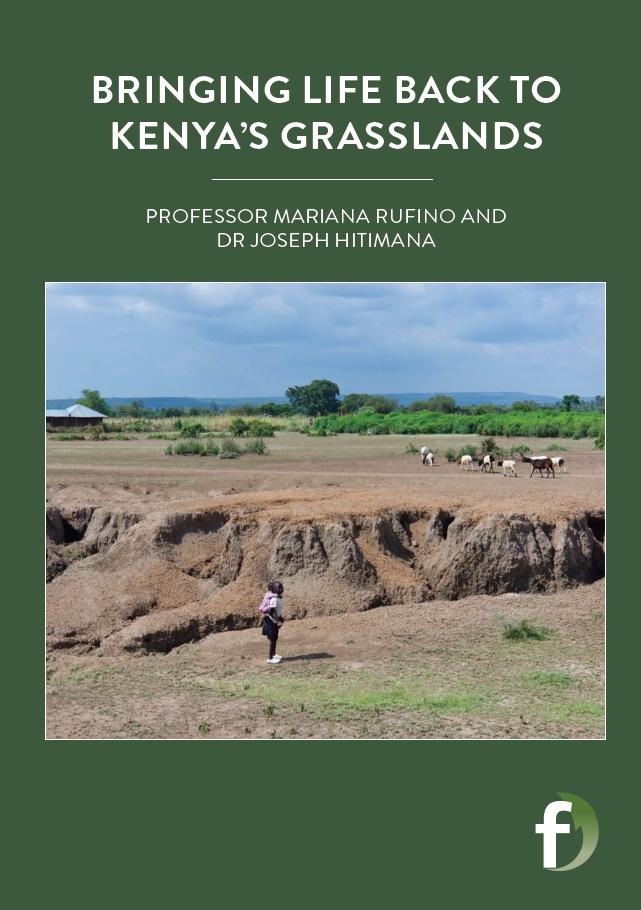

Bringing life back to Kenya’s grasslands

Land degradation causes soils to become less fertile, resulting in lower productivity in agricultural regions and decreased biodiversity. Led by Professor Mariana Rufino at Lancaster University, UK, an international team of researchers, including Dr Joseph Hitimana at the University of Kabianga in Kenya, is working with Kenyan farmers to find solutions to this problem. The ReDEAL project is utilising a community-focused, bottom-up approach to help provide Kenyan farmers with the tools and knowledge to restore their soils

TALK LIKE AN AGRICULTURAL SCIENTIST

BIODIVERSITY – the variety of life within an ecosystem

BOTTOM-UP APPROACH – in land management, an approach that involves empowering the users of the land, such as farmers, giving them agency to make their own decisions and to implement solutions

ECOSYSTEM – a biological community of organisms and the physical environment with which they interact

MONOCULTURE – a crop system that involves only a single species in a field at a time

LAND DEGRADATION – a decrease in the quality and productivity of soils

LAND RESTORATION – taking measures to return an area to its former state, such as through improving soils and/or promoting biodiversity

TOP-DOWN APPROACH – in land management, an approach that involves issuing legislation or regulations that land users must follow, which often does not consider the needs of local people

Around a quarter of all land in the world is degraded, and this amount is increasing. Land degradation is defined by a loss in soil quality, which can involve loss of organic matter, decline in nutrient availability and/or erosion. As soils become less fertile, biodiversity decreases and agricultural yields fall.

“Land degradation can happen as a result of various natural and human activities,” says Professor Mariana Rufino, an agricultural scientist at Lancaster University. These include climatic changes, intensive agriculture and over-grazing of livestock.

Sub-Saharan Africa is a land degradation hotspot, making it a focal point for restoration projects. “The problem is particularly urgent here as land degradation reduces crop and livestock productivity, damaging the livelihoods of farming communities and making them more vulnerable to climate change,” says Mariana. It also jeopardises neighbouring ecosystems. As existing agricultural land becomes degraded and therefore less productive, farmers may convert surrounding forests and grasslands into farmland.

PROJECT REDEAL: CONNECTING SCIENCE WITH COMMUNITIES

Mariana is leading the ReDEAL (Restoring Degraded African Landscapes) project, where an interdisciplinary team of researchers is hoping to reverse the trend of land degradation at two sites in Kenya: Kericho and Lower Nyando. As well as addressing the underlying science of land degradation, they are engaging with local farmers to understand the social and economic pressures faced by communities, ensuring the land restoration practices they develop will persevere far beyond the project’s lifespan.

However, success of the project depends upon the researchers having the same objectives as the people they aim to support. “From household surveys, we learnt that farmers and scientists have different definitions for degraded grasslands,” says Dr Joseph Hitimana, an agricultural and forestry scientist at the University of Kabianga. “Therefore, we need to ensure we build a shared understanding and work towards a common goal.” The team is collaborating with farmers to understand what properties they require from a productive grassland, and how these can be integrated with key features of resilient grasslands.

“Farmers have different priorities to scientists,” says Joseph. “In Kenya, farmers rely on grasslands to feed their cattle, which in turn feed their families and provide a source of income.” Farmers, therefore, have a vested interest in avoiding land degradation. However, limited income often means farmers must prioritise the short-term picture, ensuring they have enough food and income for the current year, rather than considering the long-term picture of whether their land is degrading. “Farmers may overlook early signs of land degradation if they are not currently impacting their production goals,” explains Mariana.

Another factor is the popularisation of a western style of agriculture, which typically involves large areas of monoculture crops or low-diversity grasslands. This style of agriculture, though it can lead to significant short-term productivity increases, can exacerbate degradation when soil nutrients are depleted and the biology of the soil is affected by the use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides.

“As scientists, we hold very particular views on degradation, founded in biophysical measures and indicators of soil functionality,” says Joseph. “However, these scientific measures do not necessarily consider the important social and economic pressures that farmers face when making decisions about their land.” Reconciling these two contrasting perspectives of land degradation between farmers and scientists is a key aim of the project.

ECOLOGICAL LESSONS

By working with local farmers, the team has identified that increasing plant biodiversity could be a potential solution for restoring degraded land in Kenya and other Sub-Saharan regions. “Manipulating plant biodiversity on degraded land can enhance soil functions and increase the resilience of farming,” explains Mariana. “We have found that more diverse mixtures of plants rapidly enhance soil properties during the early stages of restoration, supporting the recovery of soils.” Different plants have different functions in ecosystems, such as mobilising nutrients within the soil and as key sources of food for insects, some of the critical pollinators that fertilise crops.

Farmers provided the team with their knowledge of local plant species, and the researchers conducted experiments to grow these plants in different conditions. “Selected species were grown in pots with soils taken from our study sites in Kericho and Lower Nyando,” says Mariana. “This enabled us to learn which traits allow plants to grow under different soil conditions.” The team has now identified which selections of plant species grow most successfully in soils of various states of degradation.

At the study sites, the team is also investigating how these combinations of plants respond to different land treatments, such as tilling the soil and using manure as fertiliser. “We’re assessing which combinations of grassland management practices are most effective for restoration, as well as which are most attractive for implementation by the farmers,” says Joseph. The most important feature of any land restoration scheme is that it must be desirable for local farmers. If it is expensive, time-consuming or reduces the productivity of their land in the short-term, farmers will have no incentive to participate.

The team has also investigated different methods of livestock management, surveying how land degradation is affected by different cattle numbers, grazing regimes, availability of feeds, and interactions with current restoration attempts. “By integrating this information with farmers’ needs and wants, we can design bespoke land management recommendations that best fit their aspirations,” says Mariana.

A BOTTOM-UP APPROACH

‘Top-down’ approaches, which involve governments or scientists telling farmers what to do, are often unsuccessful. Enforcing regulations is expensive, logistically challenging and ignores the needs of the individuals whose livelihoods are affected. These approaches often neglect to consider the variability in different areas, attempting to give the same solution for all regions when in fact a more tailored approach is needed. Designing a tailored approach requires involvement from those who best understand the land – the farmers themselves.

Therefore, Project ReDEAL advocates a ‘bottom-up’ approach instead. “We want our initiatives to be taken over and run by local farmers and local institutions,” says Rachael Middleton, the research administrator for the project. “The science-based solutions we develop need to be cost-effective for farmers and must consider their livelihoods.” The farmers know their land better than anyone, so are best placed for implementing the most effective solutions. “Farmers need to have the power to make decisions and design solutions for the challenges they encounter on their land,” explains Rachael. “This is vital for socio-economic development in the region.”

The ultimate aim of ReDEAL is for the land restoration methods developed during the project to be carried forward by local farmers. The team is hosting workshops and training events to teach farmers, agricultural students and land management agencies throughout Kenya how to implement these land management solutions. When the project ends, these outreach and engagement measures will ensure the legacy of the project lives on.

PROFESSOR MARIANA RUFINO

PROFESSOR MARIANA RUFINO

Professor of Agricultural Systems, Lancaster University, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Agricultural Sciences

DR JOSEPH HITIMANA

Dean of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources, University of Kabianga, Kenya

FIELDS OF RESEARCH: Agricultural Sciences, Forestry

RESEARCH PROJECT: Investigating methods for promoting land restoration and using a bottom-up approach to promote these methods among rural communities in Kenya

FUNDER: UK Research and Innovation’s Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) as part of the Global Challenges Research Fund

ABOUT AGRICULTURAL SCIENCE

Agricultural science encompasses a wide range of disciplines, and the ReDEAL project highlights how this interdisciplinarity is essential for tackling the issue of land degradation. Agricultural scientists may also address other environmental problems caused by agriculture, such as depletion of water supplies, overuse of fertilisers and pesticides, and loss of biodiversity due to agricultural intensification.

WHAT DIFFERENT SKILLSETS ARE NEEDED TO ADDRESS LAND DEGRADATION?

“Land degradation results from multiple interacting factors, which means there is a need to include expertise from different disciplines,” says Rachael. “It’s not just a biological issue, as degradation and restoration both impact the human communities that use the land. The ReDEAL project addressed this by building a diverse team of ecologists, agronomists, soil scientists, anthropologists, social scientists, environmental scientists and geographers.”

WHY SHOULD LAND MANAGEMENT BE COMMUNITY-BASED?

“Communities are the owners of the land and rely on it for their livelihoods and income generation,” says Joseph. “However, communities often lack the resources or exposure to new methods needed to develop more sustainable ways of land management. Scientists can help empower rural communities to develop effective resource management skills. Blending traditional knowledge in resource management results in sustainable development and provides communities with a greater sense of ownership and social pride. The effectiveness of this process gives me hope for the future.”

HOW CAN LAND RESTORATION BENEFIT FUTURE GENERATIONS?

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM249

BIODIVERSITY – the variety of life within an ecosystem

BOTTOM-UP APPROACH – in land management, an approach that involves empowering the users of the land, such as farmers, giving them agency to make their own decisions and to implement solutions

ECOSYSTEM – a biological community of organisms and the physical environment with which they interact

MONOCULTURE – a crop system that involves only a single species in a field at a time

LAND DEGRADATION – a decrease in the quality and productivity of soils

LAND RESTORATION – taking measures to return an area to its former state, such as through improving soils and/or promoting biodiversity

TOP-DOWN APPROACH – in land management, an approach that involves issuing legislation or regulations that land users must follow, which often does not consider the needs of local people

Around a quarter of all land in the world is degraded, and this amount is increasing. Land degradation is defined by a loss in soil quality, which can involve loss of organic matter, decline in nutrient availability and/or erosion. As soils become less fertile, biodiversity decreases and agricultural yields fall.

“Land degradation can happen as a result of various natural and human activities,” says Professor Mariana Rufino, an agricultural scientist at Lancaster University. These include climatic changes, intensive agriculture and over-grazing of livestock.

Sub-Saharan Africa is a land degradation hotspot, making it a focal point for restoration projects. “The problem is particularly urgent here as land degradation reduces crop and livestock productivity, damaging the livelihoods of farming communities and making them more vulnerable to climate change,” says Mariana. It also jeopardises neighbouring ecosystems. As existing agricultural land becomes degraded and therefore less productive, farmers may convert surrounding forests and grasslands into farmland.

PROJECT REDEAL: CONNECTING SCIENCE WITH COMMUNITIES

Mariana is leading the ReDEAL (Restoring Degraded African Landscapes) project, where an interdisciplinary team of researchers is hoping to reverse the trend of land degradation at two sites in Kenya: Kericho and Lower Nyando. As well as addressing the underlying science of land degradation, they are engaging with local farmers to understand the social and economic pressures faced by communities, ensuring the land restoration practices they develop will persevere far beyond the project’s lifespan.

However, success of the project depends upon the researchers having the same objectives as the people they aim to support. “From household surveys, we learnt that farmers and scientists have different definitions for degraded grasslands,” says Dr Joseph Hitimana, an agricultural and forestry scientist at the University of Kabianga. “Therefore, we need to ensure we build a shared understanding and work towards a common goal.” The team is collaborating with farmers to understand what properties they require from a productive grassland, and how these can be integrated with key features of resilient grasslands.

“Farmers have different priorities to scientists,” says Joseph. “In Kenya, farmers rely on grasslands to feed their cattle, which in turn feed their families and provide a source of income.” Farmers, therefore, have a vested interest in avoiding land degradation. However, limited income often means farmers must prioritise the short-term picture, ensuring they have enough food and income for the current year, rather than considering the long-term picture of whether their land is degrading. “Farmers may overlook early signs of land degradation if they are not currently impacting their production goals,” explains Mariana.

Another factor is the popularisation of a western style of agriculture, which typically involves large areas of monoculture crops or low-diversity grasslands. This style of agriculture, though it can lead to significant short-term productivity increases, can exacerbate degradation when soil nutrients are depleted and the biology of the soil is affected by the use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides.

“As scientists, we hold very particular views on degradation, founded in biophysical measures and indicators of soil functionality,” says Joseph. “However, these scientific measures do not necessarily consider the important social and economic pressures that farmers face when making decisions about their land.” Reconciling these two contrasting perspectives of land degradation between farmers and scientists is a key aim of the project.

ECOLOGICAL LESSONS

By working with local farmers, the team has identified that increasing plant biodiversity could be a potential solution for restoring degraded land in Kenya and other Sub-Saharan regions. “Manipulating plant biodiversity on degraded land can enhance soil functions and increase the resilience of farming,” explains Mariana. “We have found that more diverse mixtures of plants rapidly enhance soil properties during the early stages of restoration, supporting the recovery of soils.” Different plants have different functions in ecosystems, such as mobilising nutrients within the soil and as key sources of food for insects, some of the critical pollinators that fertilise crops.

Farmers provided the team with their knowledge of local plant species, and the researchers conducted experiments to grow these plants in different conditions. “Selected species were grown in pots with soils taken from our study sites in Kericho and Lower Nyando,” says Mariana. “This enabled us to learn which traits allow plants to grow under different soil conditions.” The team has now identified which selections of plant species grow most successfully in soils of various states of degradation.

At the study sites, the team is also investigating how these combinations of plants respond to different land treatments, such as tilling the soil and using manure as fertiliser. “We’re assessing which combinations of grassland management practices are most effective for restoration, as well as which are most attractive for implementation by the farmers,” says Joseph. The most important feature of any land restoration scheme is that it must be desirable for local farmers. If it is expensive, time-consuming or reduces the productivity of their land in the short-term, farmers will have no incentive to participate.

The team has also investigated different methods of livestock management, surveying how land degradation is affected by different cattle numbers, grazing regimes, availability of feeds, and interactions with current restoration attempts. “By integrating this information with farmers’ needs and wants, we can design bespoke land management recommendations that best fit their aspirations,” says Mariana.

A BOTTOM-UP APPROACH

‘Top-down’ approaches, which involve governments or scientists telling farmers what to do, are often unsuccessful. Enforcing regulations is expensive, logistically challenging and ignores the needs of the individuals whose livelihoods are affected. These approaches often neglect to consider the variability in different areas, attempting to give the same solution for all regions when in fact a more tailored approach is needed. Designing a tailored approach requires involvement from those who best understand the land – the farmers themselves.

Therefore, Project ReDEAL advocates a ‘bottom-up’ approach instead. “We want our initiatives to be taken over and run by local farmers and local institutions,” says Rachael Middleton, the research administrator for the project. “The science-based solutions we develop need to be cost-effective for farmers and must consider their livelihoods.” The farmers know their land better than anyone, so are best placed for implementing the most effective solutions. “Farmers need to have the power to make decisions and design solutions for the challenges they encounter on their land,” explains Rachael. “This is vital for socio-economic development in the region.”

The ultimate aim of ReDEAL is for the land restoration methods developed during the project to be carried forward by local farmers. The team is hosting workshops and training events to teach farmers, agricultural students and land management agencies throughout Kenya how to implement these land management solutions. When the project ends, these outreach and engagement measures will ensure the legacy of the project lives on.

PROFESSOR MARIANA RUFINO

PROFESSOR MARIANA RUFINO

Professor of Agricultural Systems, Lancaster University, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Agricultural Sciences

DR JOSEPH HITIMANA

Dean of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources, University of Kabianga, Kenya

FIELDS OF RESEARCH: Agricultural Sciences, Forestry

RESEARCH PROJECT: Investigating methods for promoting land restoration and using a bottom-up approach to promote these methods among rural communities in Kenya

FUNDER: UK Research and Innovation’s Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) as part of the Global Challenges Research Fund

Agricultural science encompasses a wide range of disciplines, and the ReDEAL project highlights how this interdisciplinarity is essential for tackling the issue of land degradation. Agricultural scientists may also address other environmental problems caused by agriculture, such as depletion of water supplies, overuse of fertilisers and pesticides, and loss of biodiversity due to agricultural intensification.

WHAT DIFFERENT SKILLSETS ARE NEEDED TO ADDRESS LAND DEGRADATION?

“Land degradation results from multiple interacting factors, which means there is a need to include expertise from different disciplines,” says Rachael. “It’s not just a biological issue, as degradation and restoration both impact the human communities that use the land. The ReDEAL project addressed this by building a diverse team of ecologists, agronomists, soil scientists, anthropologists, social scientists, environmental scientists and geographers.”

WHY SHOULD LAND MANAGEMENT BE COMMUNITY-BASED?

“Communities are the owners of the land and rely on it for their livelihoods and income generation,” says Joseph. “However, communities often lack the resources or exposure to new methods needed to develop more sustainable ways of land management. Scientists can help empower rural communities to develop effective resource management skills. Blending traditional knowledge in resource management results in sustainable development and provides communities with a greater sense of ownership and social pride. The effectiveness of this process gives me hope for the future.”

HOW CAN LAND RESTORATION BENEFIT FUTURE GENERATIONS?

“ReDEAL is addressing a complex and pressing problem by building a solution for the future that incorporates ecological, social and economic concerns,” says Mariana. “I am convinced we need to create ‘green jobs’ to engage young people in reconnecting with the land that feeds us, while helping society build resilience to environmental changes. This would also help address the serious issue of youth unemployment in Africa.”

EXPLORE A CAREER IN AGRICULTURAL SCIENCE

• Mariana recommends seeking summer placements with land management organisations such as Natural England (www.naturalengland.gov.uk), or with farmers or farming organisations such as the National Farmers’ Union (www.nfuonline.com). There is an increasing awareness in such organisations to improve sustainability and resilience.

• Lancaster University runs many outreach initiatives, including summer schools and STEM days for school students (www.lancaster.ac.uk/sci-tech/about-us/outreach). The Lancaster Environment Centre provides support to schools and teachers (www.lancaster.ac.uk/lec/about-us/engagement).

• Prospects gives an overview of possible career paths in agricultural sciences and provides links to potential work experience opportunities in the UK and abroad: www.prospects.ac.uk/careers-advice/what-can-i-do-with-my-degree/agriculture

• At school, study biology, chemistry and geography for a foundation in agricultural science. Humanities subjects will help you understand the social aspects of agricultural activities, while maths will be useful for data analysis.

• Some universities provide degrees in agricultural sciences, but degrees in ecology, plant or soil science, geography or environmental science could also lead to a career in agriculture or land restoration.

HOW DID MARIANA BECOME AN AGRICULTURAL SCIENTIST?

I grew up on a farm in Argentina and spent lots of time outdoors. As a young child, I had an insatiable thirst for knowledge – I wanted to know everything! I have always been fascinated by science, then, as a teenager, I did a geography project about the rivers of Africa. I became fascinated by that mysterious continent and wanted to explore it.

I knew I wanted to go to university as I was passionate about learning. After completing a degree in agronomy in Argentina, I worked as a research assistant for a couple of years. I wanted to see more of the world and was lucky enough to secure a master’s degree in the Netherlands, where I met a professor who helped me establish my first research project in Africa.

I have now spent almost 20 years conducting research in this beautiful continent. I have visited many countries and lived in Kenya for six years. My hope is that environmental problems in Sub-Saharan Africa do not increase.

Our relationship with nature has changed since I was a child. This is especially obvious in high-income countries where many of us have adopted urban lifestyles and lost our connection to the natural world. People no longer know where food comes from.

I have always embraced opportunities and challenges that have come my way, which has helped me build experience as a researcher. It is important to keep your eyes open to opportunities, to try new things and to ask others for help. I have always been amazed to see how many people are willing to help when I ask.

HOW DID JOSEPH BECOME AN AGRICULTURAL AND FORESTRY SCIENTIST?

I was an attentive student when I was younger. I enjoyed listening to stories and playing during my free time. Mathematics was my favourite subject, but I was curious to learn about others, too. I wanted to pursue applied sciences or to be a medical doctor.

I have always endeavoured to pursue my studies and work with passion. I enjoyed my university education, and when I was granted a lecturing position, I embraced the opportunity to teach students and work in harmony with other academics. I am now the Dean of the School of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources, a role which has a lot of responsibility. I focus on achieving clear goals, using my own energy and skills but also looking for support from others where needed.

As a scientist, I am motivated by a sense of responsibility to humanity. I want to use my work and my abilities to make a positive impact, no matter how small it may be. I value self-motivation and am guided by the philosophies of positive thinking and teamwork.

I take great pride in training graduates to become competent and confident scientists who positively contribute to the welfare of our environment and people. I am also proud of my published research, which has engaged the international community and promoted a sense of shared values and aspirations beyond geographical boundaries.

In the future, I hope to build the research and training capacity in my university through international partnerships. I wish to reveal the coexistence between the natural environment, its resources and communities, which will enable the real harmony between people and nature to prevail.

MARIANA AND JOSEPH’S TOP TIPS

01 Be brave, try new things and don’t listen to that inner voice that doubts your abilities.

02 To live a rewarding life, we need to find out what matters to us, which involves encountering a variety of experiences.

03 Whatever path you aspire to follow, pursue it with passion and honesty.

04 The power of positive thinking is real. Think positively, nurture creativity and live in harmony with yourself.

Do you have a question for Mariana or Joseph?

Write it in the comments box below and Mariana or Joseph will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)