Can behavioural interventions improve biological health outcomes?

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the US, accounting for around one in every five deaths. However, some groups in society are at higher risk than others. At the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill in the US, Dr Yamnia I. Cortés is investigating whether a community-based behavioural intervention can improve cardiovascular health outcomes for perimenopausal Latinas.

TALK LIKE A NURSE SCIENTIST

Cardiovascular — relating to the heart and blood vessels

Clinical trial — a research study performed on people that evaluates a medical, surgical or behavioural intervention

Community-based research — research taking place in community settings and where community members have a say in the research process

Health equity — when everyone has the opportunity to reach their best health outcomes

Latino/a/x — an individual of Latin American descent (i.e., Mexican, Central American, South American or from some Caribbean islands)

Menstruation — the process whereby approximately once a month a woman discharges blood from the lining of her uterus

Oestrogen — the primary female reproductive hormone

Perimenopause — the transition that occurs before a woman stops menstruating at menopause

While everyone experiences changes in their health as they get older, women who menstruate are particularly at risk from certain health problems that may occur during perimenopause. “There are three major reproductive stages in women who menstruate: premenopause, perimenopause and postmenopause,” explains Dr Yamnia I. Cortés, a nurse scientist at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. Premenopause begins with menarche, the first menstruation, which typically happens when a girl is between 10 and 16 years old and marks the beginning of the reproductive years. Women usually enter perimenopause in their 40s or 50s, when they may notice changes in their menstrual cycle. A woman has reached menopause when she has not menstruated for 12 consecutive months, at which point she enters the postmenopausal stage of life.

Perimenopause is a significant biological transition for women who menstruate. During this time (which, on average, lasts four years), oestrogen levels in the body decrease, leading to several symptoms associated with perimenopause and an increase in certain health risks. “Oestrogen is a female reproductive hormone typically produced in the ovaries,” explains Yamnia. “It also plays an important role in other parts of the body, such as the bones, brain and heart. The decline of this hormone during perimenopause can lead to hot flashes, sleep disturbances, depressive symptoms, bone loss, body fat accumulation and rising cholesterol.”

Why are Latinas at greater risk of cardiovascular disease during perimenopause?

While the biological process of declining oestrogen leads to health changes during perimenopause, sociocultural and environmental factors can also contribute to the severity of symptoms and health risks, such as cardiovascular disease (CVD). Most perimenopause research in the US has collected data from non-Latina white women, meaning that women of other races or ethnicities (who are more likely to experience negative sociocultural and environmental factors) are underrepresented in current knowledge about perimenopause health outcomes. Yamnia is passionate about health equity and aims to initiate change by focusing her research on perimenopausal Latinas.

Latinas are particularly at risk of CVD during perimenopause as they are more likely to experience adverse sociocultural factors such as discrimination, social isolation and stress. “Many Latinas live in neighbourhoods with fewer grocery stores and so lack access to healthy food,” says Yamnia. “Living in disadvantaged neighbourhoods increases stress, limits physical activity and increases sedentary behaviour, which influence biologic CVD risk factors.” As a result, Latinas are at significantly greater risk of developing CVD than non-Latina white women.

Developing a behavioural intervention

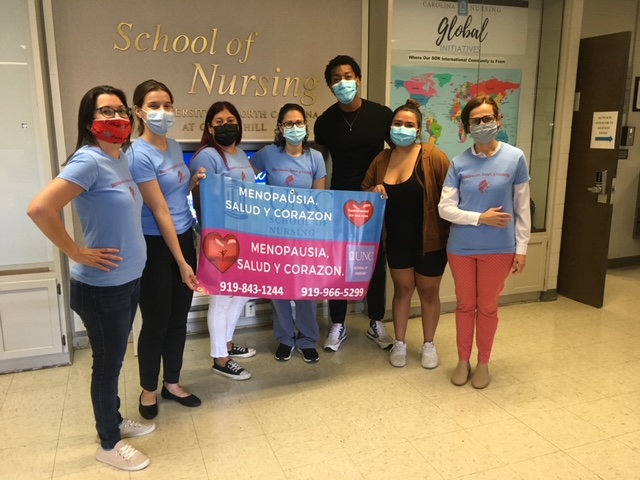

Yamnia hopes to reduce the risk of CVD in perimenopausal Latinas by developing a community-based and culturally tailored behavioural intervention. This intervention involves teaching nutrition education, physical activities, stress management techniques and coping skills to perimenopausal Latinas. Yamnia and her team are evaluating whether this leads to improved biological health outcomes.

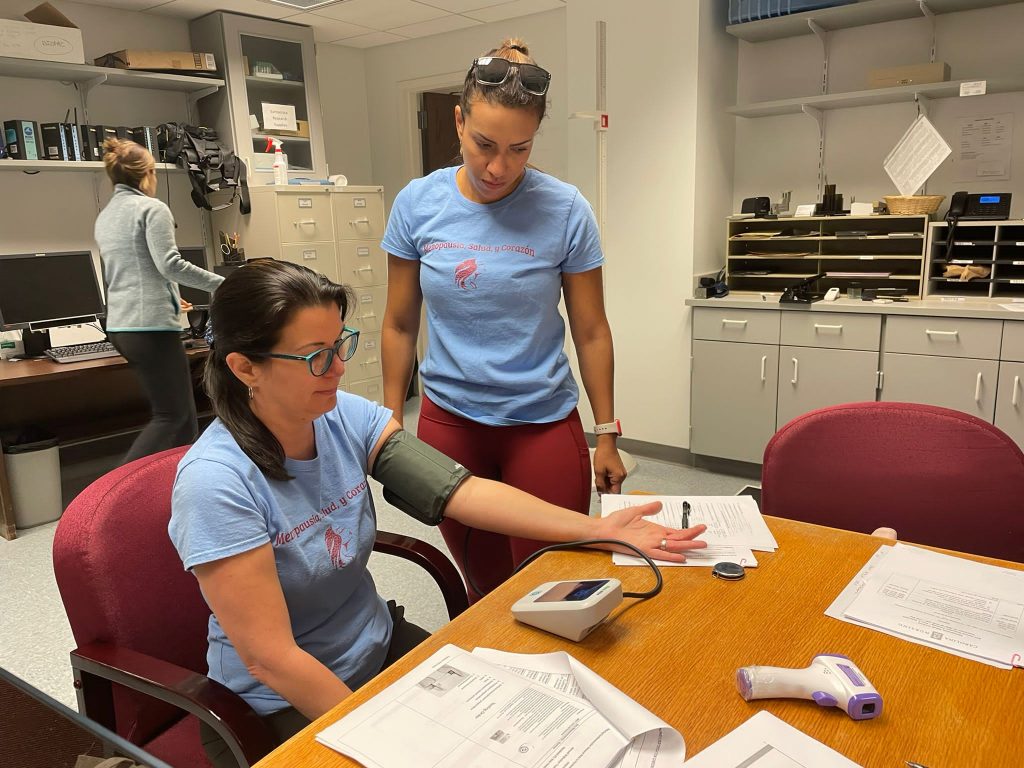

The nutrition education programme involves teaching participants to understand food labels and sharing healthy recipes. Physical activity sessions include various exercises, such as stretching and Zumba, while stress management techniques taught to participants include mindfulness, aromatherapy and doing arts and crafts. “These behaviours can lead to weight loss, lower blood pressure, lower blood sugar, lower cholesterol and healthier arteries, all of which increase cardiovascular health,” explains Yamnia.

Why is it important that the intervention is culturally tailored?

“Culturally tailoring an intervention means taking into consideration the needs and preferences of the target culture or community,” says Yamnia. “This makes the intervention more applicable to the values and daily life of individuals.”

To ensure it was relevant and accessible, Yamnia specifically tailored the behavioural intervention to Latinas. “We delivered the intervention in a way that addressed Latino cultural values such as respeto (respect), familismo (loyalty to family) and confianza (trust),” she explains. Sessions were led by Latinas who could identify with participants, and all materials were available in Spanish and English. The recipes taught to participants were healthier versions of traditional dishes from multiple Latino backgrounds, including Mexican, Puerto Rican and Argentinian, to reflect the diversity within the Latino community. And the exercises taught to participants were all suitable for the space and materials that were available to the women in their homes.

Testing the intervention

To test the effectiveness of the intervention, Yamnia and her team conducted a clinical trial. They enrolled 40 perimenopausal Latinas, who were randomly assigned either to take part in the intervention or to the control group that did not participate (though women in the control group had the opportunity to receive the intervention after the clinical trial was completed). The 20 women receiving the intervention were invited to participate in the programme, which consisted of twelve weekly sessions followed by three monthly sessions. Each session consisted of 45 minutes of nutrition education, 45 minutes of physical activity and 15 minutes of stress management.

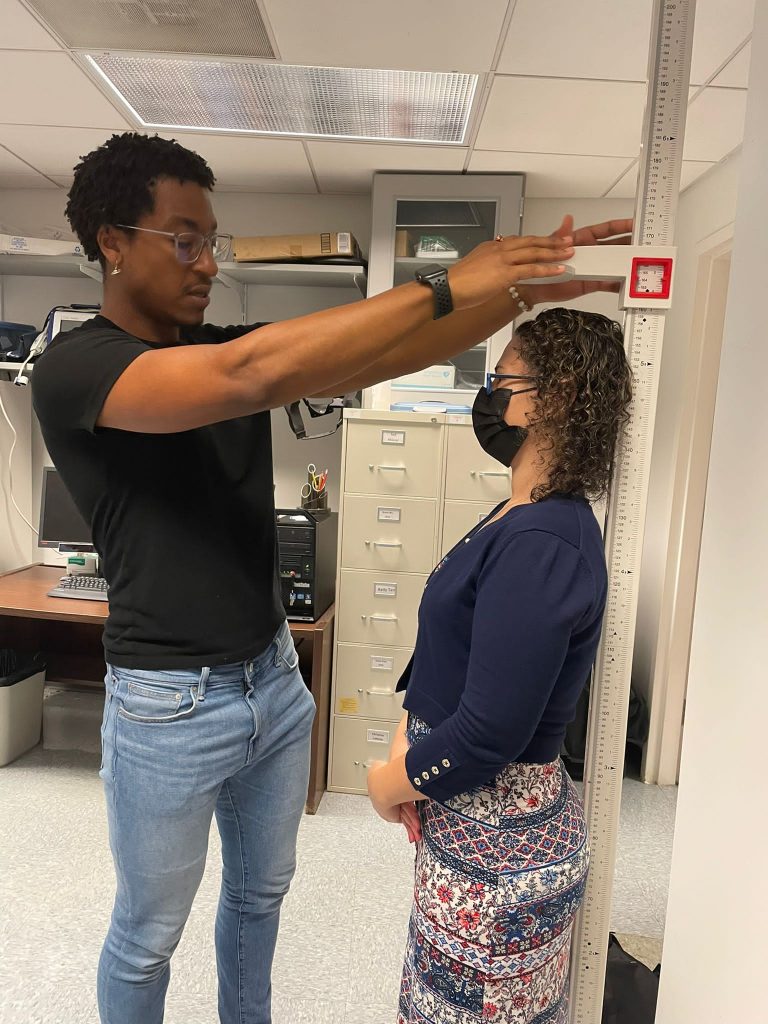

Yamnia and her team collected the data from all 40 women at three points during the study – before the intervention began, immediately after the intervention finished and six months after the intervention had ended. “This included a questionnaire about sociodemographic details, medical history, menopause symptoms, stress, sleep, diet and physical activity,” Yamnia says. “We also collected blood samples to test for fats (including cholesterol), sugars and proteins, and we collected hair samples to measure cortisol levels (a hormone that indicates stress levels).”

Does the intervention reduce CVD for perimenopausal Latinas?

The results from the team’s clinical trial show that women who participated in the intervention had lower stress and lower blood pressure than women in the control group. “This suggests the intervention may be successful in reducing CVD risk factors,” says Yamnia. However, while the study shows it is feasible to conduct behavioural interventions to improve health outcomes for perimenopausal Latinas, the team realised that the intervention in its current form is too long. “Of the 20 women in the intervention group, only nine attended more than half of the sessions and only four attended more than 80% of the sessions.”

What next?

Yamnia now hopes to implement similar programmes in different locations, allowing more perimenopausal Latinas to take advantage of the health benefits of behavioural interventions. However, a key finding from her initial study was that many of the participants did not have health insurance. This suggests that behavioural interventions alone are not enough to improve the health of Latinas, as sociocultural and structural factors, such as lack of access to healthcare, must be addressed as well.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM373

We need more nurse scientists, healthcare practitioners and policymakers who are passionate about health equity to ensure that everyone, regardless of ethnicity, gender or socioeconomic status, can lead a healthy life.

Dr Yamnia I. Cortés

Dr Yamnia I. Cortés

School of Nursing, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, USA

Fields of research: Nursing Science, Women’s Health, Cardiovascular Epidemiology

Research project: Investigating health outcomes for perimenopausal Latinas

Funders: US National Institutes of Health (NIH) – National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities; Betty Irene Moore Fellowship for Nurse Leader and Innovators

ABOUT NURSING SCIENCE

Nurse scientists are nurses who design and conduct health-related research projects, lead research teams, and often teach in academic settings. Like other scientists, they publish their research results in scientific journals and share their findings with the public through presentations, news outlets and social media.

The importance of women’s midlife health

There is a difference between chronologic ageing and reproductive ageing. “Some health factors that increase the risk of CVD, such as weight and blood pressure, naturally increase with age,” explains Yamnia. “Others, such as body fat and cholesterol, increase more rapidly during perimenopause.” When assessing midlife health issues in women who menstruate, it is important to determine which changes are due to general ageing, and which are due to perimenopause.

Women’s midlife health is important for everyone in society, regardless of gender or age. “We all have important women in our life – family members, friends, teachers and colleagues,” says Yamnia. “To protect their health and quality of life, we need more healthcare providers, researchers, social workers, politicians and community members interested in this topic.”

The importance of inclusive health policies

As well as researching women’s midlife health, Yamnia’s research group, the Cortés MenoLab, also advocates for policies that promote women’s midlife health equity. The team does this by working with policymakers and national health organisations to ensure health policies are effective, relevant and inclusive, and by providing advice and guidance for clinical care and research.

A key aspect of this is promoting health research in marginalised populations. “When marginalised populations are not included in health research, we risk not understanding how certain health issues affect these populations,” explains Yamnia. “We also risk developing health procedures, medications or behavioural interventions that do not work in marginalised groups. Therefore, we need to include as many people as possible, from all different walks of life, in health research.”

Pathway from school to nursing science

• Yamnia recommends taking courses in sciences (such as biology, chemistry, anatomy and physiology), statistics and public health. You should also take any other courses that interest you. “My interest in Latina health is no accident,” says Yamnia. “In college, I took classes in Latino/a studies and gender studies.”

• Completing a Bachelor of Science degree in nursing will qualify you to practise nursing in a clinical setting. To become a nursing science researcher, you will then need to complete a PhD.

• However, there is no set path to becoming a nurse scientist. Yamnia studied biology and Latino/a studies, then public health before turning to nursing. “My path was not typical or linear, and that’s okay!” she says. “We can get to the same goal using different paths.”

Explore careers in nursing science

• “Although I am a nurse scientist, this is not the only career available for individuals interested in women’s health,” says Yamnia. “I have worked on women’s health issues with epidemiologists, biostatisticians, physicians, psychologists, social workers, sociologists, nutritionists and more!”

• Yamnia recommends looking for work experience opportunities to give you a better sense of whether you will enjoy being a nurse scientist. “This is the best way to tell whether a certain career fits with your aspirations,” she says. “Look for opportunities in high school and college to participate in research projects, work as a nurse aid or shadow nurse scientists to get a sense of their day-to-day work.”

• Explore Health Careers has information about careers in nurse science, as well as other health-related fields: explorehealthcareers.org/career/nursing/nurse-researcher

• This article explains the important contribution nurse scientists bring to health research: www.wolterskluwer.com/en/expert-insights/who-are-nurse-scientists

Meet Dr Yamnia I. Cortés

I am passionate about health equity, especially for Latinas, because I grew up in the Bronx, New York, where many people in my community suffered from asthma, diabetes and heart disease. The Bronx has one of the highest rates of asthma in the US due to the exhaust fumes from nearby highways. In my neighbourhood, there were long waits to see a healthcare provider, few healthy options were available in the grocery store, and we had no safe park spaces.

I received a scholarship to attend a private high school, and the neighbourhoods surrounding it were a stark contrast to my own. These neighbourhoods had green spaces, fresh fruits and vegetables at the market, and well-equipped health centres. This prompted me to ask why these differences existed and how they impacted health.

In middle school, I joined a social justice programme where I participated in community service projects. I learnt how to affect social change when we demanded the clean-up of the Bronx River and the development of a park for the neighbourhood. I also served as a peer educator, presenting health-related workshops in the local community. In high school, I had the opportunity to complete a summer programme where I conducted research in a laboratory at a college and shadowed physicians in a hospital.

I pursued my interest in social justice and health at college. Alongside my studies in biology and Latino/a studies, I worked part-time in a biochemistry laboratory and had the chance to join a medical mission trip to the Dominican Republic. As a child, I had translated for my mother during many interactions with health providers, and, on this trip, I acted as a translator for a group of obstetricians and gynaecologists.

I was the first person in my family to graduate from college. After completing my degree in biology and Latino/a studies, I then did a degree in public health. Some years later, I returned to university to complete a nursing degree. In my work as a nurse, I most enjoyed providing patients with health education.

All my experiences gave me an interest in community work, clinical work and research, so I did a PhD in nursing science. I now love my work as a nurse researcher conducting community engaged research, as it allows me to work with people in the community, listen to their stories and advise them about health.

Yamnia’s top tips

1. Don’t be discouraged by failures. The difference between success and failure is the number of times you keep trying.

2. You don’t have to reach your goals by following the same journey as the person next to you.

3. Self-worth and self-compassion are better motiving factors than any titles or awards.

Meet some members of the Cortés Menolab

Andrea Cazales

PhD Student

“I enjoy being part of a team that reflects the community it serves. I like that we use strength-based approaches to address menopause health inequities experienced by historically marginalised communities. The Cortés MenoLab does an exceptional job of uplifting not just the communities it serves, but also its members.”

Latesha K. Harris

PhD Student

“While in nursing school, I learnt that women have a unique set of healthcare challenges and are at higher risk of developing certain conditions than men, such as heart disease and diabetes. As a nurse, I noticed how women experience health promotion, disease prevention and illness differently, and this inspired me to pursue a career as a nurse scientist. The leading causes of death for women are preventable. My passion for helping everyone achieve their best health set me on a path to investigate women’s health disparities.”

Alyssa Portes

PhD Student

“As a first-generation Latinx student, I have a deep interest in learning about the racial and ethnic health disparities marginalised women face. I have worked as a research assistant on several projects surrounding minority women’s health. In nursing school, I decided to pursue a PhD in nursing science to better understand risk factors for perinatal depression among Latinx mothers living in rural communities.”

Do you have a question for Yamnia?

Write it in the comments box below and Yamnia will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)