Can music be a tool for social transformation?

Social music programmes around the world are encouraging communities to sing and play their way from conflict to peace. The Arts of Inclusion (TAI), a network founded by Professor Oscar Odena at the University of Glasgow, UK, is studying the results to find out if music really does have healing powers

Life in Kinshasa is hard. Families in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s (DRC’s) capital often have no choice but to make ends meet by selling things on the hot, dusty streets. With opportunities few and far between, some people resort to violence and theft. But there is another side to the world’s largest French-speaking city. Amongst the clamour of 17 million people going about their daily lives, there is the sound of drums beating out vibrant rhythms from across the DRC’s varied musical traditions. For some, drumming has become a new way of life, allowing them to escape old habits of violence. As one man who swapped being a gang member for being a band member told The Arts of Inclusion network member Professor Lukas Pairon,

“When I play music, even when I do not eat or drink, I will forget all of that. When I am in front of my instrument, everything else does not count anymore… The only thing that matters then is the pleasure of performing music. If I would not have my musical activity, I might have abandoned my struggle in life a long time ago.” This is just one example of many people from around the world for whom music could have a life-changing impact. Social music projects aim to heal the wounds of war, give individuals new purpose, and bridge divisions between rival groups by getting people singing, dancing and playing instruments. The question is, do these social music projects really work?

Although we hear many stories about the “healing power” of music, there is a lot we do not yet know about social music projects. This is why Professor Oscar Odena, an interdisciplinary researcher at the University of Glasgow in Scotland, decided to create a global network of people studying social music projects from Colombia in South America to the DRC in Africa.

WHAT IS THE ARTS OF INCLUSION NETWORK?

By 2019, Oscar had already spent a lot of time researching social music projects. His focus had been in Northern Ireland, in the UK, where conflict between Protestant and Catholic communities led to a deeply divided society. He noticed that there were limits to the power of music to resolve these divisions – people needed time to pass after a conflict before music could bring them together again. He was left wondering how his results would compare to social music projects in different parts of the world.

The Arts of Inclusion (TAI) was built to compare and contrast social music projects on a global scale. Being bilingual in Spanish and English helped Oscar to reach out to researchers in Mexico, Colombia, Spain, England, Northern Ireland and Scotland, while Brazil and the DRC are also on the list of countries covered by TAI. By comparing projects with varying histories and cultures, Oscar hopes the network will help us understand what makes for a successful project that improves people’s lives and brings communities together. Although TAI has focused mainly on music so far, in the future the network members also want to investigate other performing arts, such as drama.

WHY DO WE NEED TO RESEARCH SOCIAL MUSIC PROJECTS?

It might seem obvious that music can bring people together. If you sing with other. people in church, at school assemblies or at gigs, you will know that special feeling of connection when your voices combine. It can be easy to forget that music can also be a way of keeping people apart. Think of the chants sung by fans of two rival football teams: in this case the music is used to express fans’ differences.

Oscar says, “There is a risk of romanticising social music practices and thinking they always work.” When he was studying projects in Northern Ireland, he saw how music was sometimes used to emphasise the divide between Catholics and Protestants, making the tensions greater rather than leading to peace. Furthermore, stories about the effect of music on individuals (such as the one this article started with) can be powerful, but this does not necessarily mean the effects on society as a whole have been significant. To be sure of this requires thorough research that takes a wide range of experiences into account.

Research will help to uncover the best way of designing a social music project so that it has the maximum benefit, and find out if there are situations where it does not work. This will mean less time spent on ineffective projects, and more people finding their way out of violence or conflict through music.

WHAT HAS TAI DISCOVERED SO FAR?

Oscar, having studied music, education and psychology, has encouraged TAI network members to use a wide variety of approaches in their research into music programmes. His collaborators include people with backgrounds ranging from social work, music, philosophy and political science, many of whom you will meet in this article. Their first big project together has been producing a new book titled Music and Social Inclusion: International Research and Practice in Complex Settings, published by Routledge in 2023.

Each chapter of the book is written by a different researcher and discusses one or more projects, from the small scale like Espace Masolo, an arts centre in Kinshasa for children who ran away from their families, up to nationwide programmes in Colombia and Mexico. As he edited these chapters, Oscar noticed some patterns in the results.

The research by TAI shows that music does not guarantee peace, but it can certainly play its part through its powerful effect on individuals. Getting involved with music helps us figure out who we are and where we belong, which in turn helps us to form good relationships with those around us. In addition, playing music is generally a positive experience, helping people who have been through conflict to express themselves and enjoy life again.

Although he aims to be objective with his research, Oscar feels that music really does have its benefits. “It may not change people’s social circumstances immediately,” he says, “but it can change the way they see themselves, which can bring increased well-being and potentially lead to positive changes.”

PROFESSOR OSCAR ODENA

PROFESSOR OSCAR ODENA

Professor of Education

School of Education and School of Interdisciplinary Studies

University of Glasgow, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Arts and Social Science

RESEARCH PROJECT: The Arts of Inclusion (TAI) – researching how music and creativity can be used as a tool for social inclusion and conflict resolution

FUNDERS: UK Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), Global Challenges Research Fund, Royal Society of Edinburgh (RSE), Scottish Funding Council (SFC)

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM318

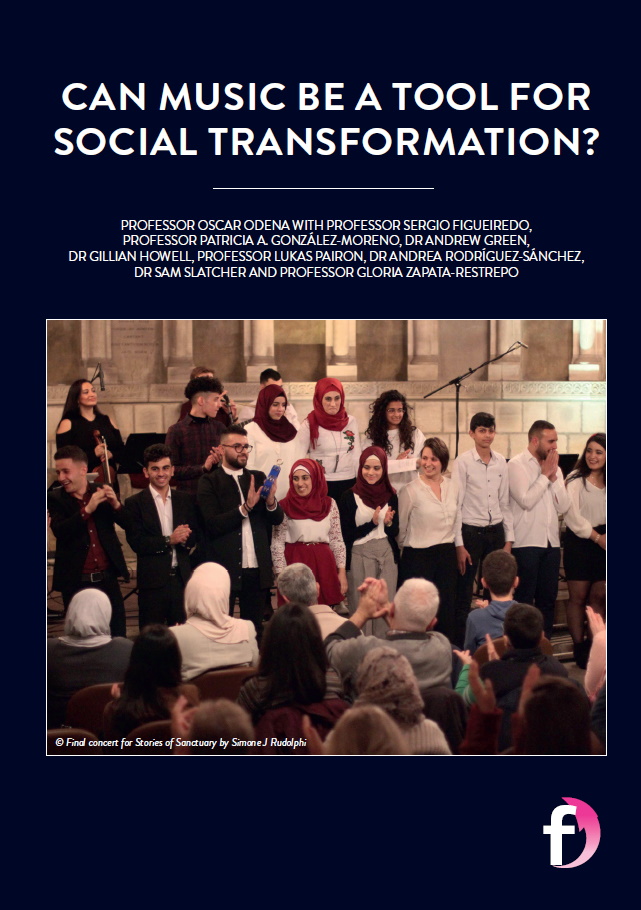

© Simone J Rudolphi

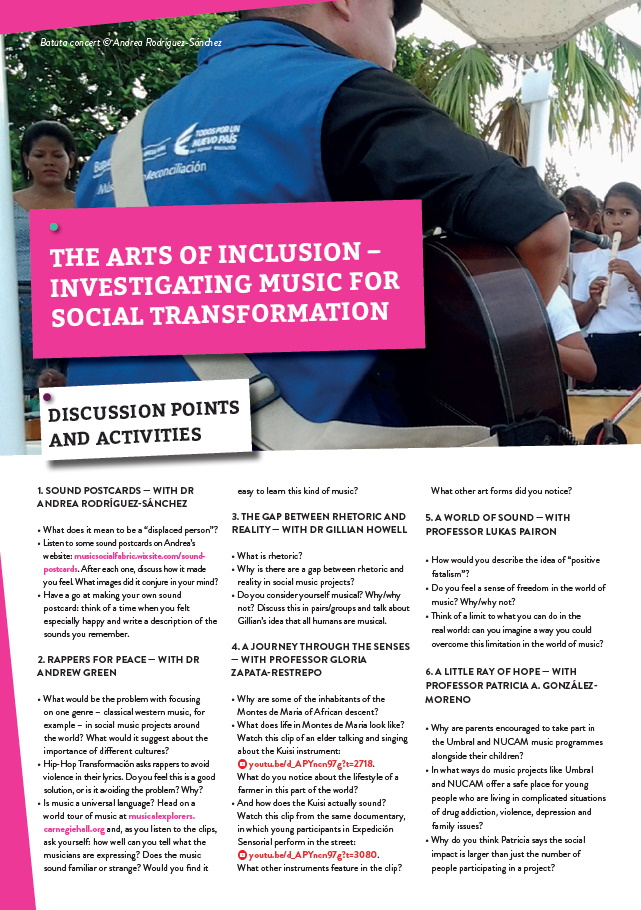

© Andrea Rodríguez-Sánchez

© Gloria Zapata-Restrepo

© Patricia A. González-Moren

© Oscar Odena

MEET SOME OF THE TAI NETWORK MEMBERS

Sound Postcards

Dr Andrea Rodríguez-Sánchez is a social worker and member of the Peace Program at the National University of Colombia. She has been unravelling the stories of displaced people through the sounds they remember from different parts of their lives.

WHY ARE PEOPLE BEING DISPLACED IN COLOMBIA?

There has been armed conflict in Colombia for over 60 years. Faced with fighting over territory and resources, much of the country’s population has been forced to move to safer areas. By 2013, over 5 million people had left their homes due to threats and violence, the majority of whom are women, children and people of indigenous or African descent (minority ethnic groups in Colombia).

Andrea says, “Civil society has always found itself in the middle of the economic and political interests at play in our country. It is a very sad situation, especially for the new generations who have to continue living or seeing these unjust situations.” Andrea lives in Bogota, the capital city of Colombia and a destination for many displaced people. Some of Andrea’s fieldwork was conducted here, as well as in three other Colombian cities (Cali, Tierralta and Florencia).

The fieldwork involved meeting and interviewing people who had been displaced and were now taking part in a social music programme.

WHAT IS MUSIC FOR RECONCILIATION?

Colombia has a number of nationwide social music programmes, including Batuta National Foundation’s Music for Reconciliation, which is aimed at victims of the conflict. One of the goals of Music for Reconciliation is to help displaced people feel part of their new communities and find a sense of belonging there.

Although Music for Reconciliation is government funded, Andrea says it “survives largely thanks to the work and initiative of the people who are involved”. She hopes that her research will highlight just how important music programmes are for transforming people’s lives and peacebuilding, providing strong evidence for better funding into the future.

WHY USE SOUND POSTCARDS?

Andrea asked the displaced people she met to tell her about the sounds they remember from before their displacement, after being displaced, and from being involved in the Music for Reconciliation programme. This technique, called sound postcards, allows her to get a vivid snapshot of certain moments in people’s lives, often revealing how they felt at the time. Take, for example, the sound postcards of a 16-year-old boy called Pedro:

BEFORE DISPLACEMENT – The birds, cows, dogs, my grandma cooking the soup and the lads playing football. You can hear that nice and clear from the mountain.

AFTER DISPLACEMENT – The cars, they sound their horns so much they’ll end up damaging them.

MUSIC FOR RECONCILIATION – The laughter, singing, the music – Pink Panther

You can access more sound postcards here:

musicsocialfabric.wixsite.com/sound-postcards/copy-of-stream-buy

MEET ANDREA

When I was younger, I loved medicine and architecture. I drew a lot of diagrams on the computer. I wasn’t clear about what I wanted to be, but I knew that these two worlds attracted me.

I really like to help people improve their lives, so I’m very happy researching how music can contribute to a better quality of life for people, especially those who have experienced violence.

Since I was a child, music has been a great joy. Whenever I can, I sing or play an instrument. For me, music is a space for authentic and simple expression. After studying it, I chose not to dedicate myself to music professionally and, perhaps, this has allowed me to have a lot of freedom; I experience music as a kind companion that is always there.

I see music as a gentle way of bringing us closer to each other, particularly in Colombia. After so many years of violence, there is a great mistrust that weakens our social fabric in a significant way. I see from my experience and studies that collective music, realised under carefully designed conditions, can contribute to social reconstruction.

Rappers for Peace

Dr Andrew Green is Associate Professor at the University of Warsaw, Poland, with an interest in social music programmes in Mexico. He has been finding out if rap battles can be used to promote peace as well as competition.

IS HIP-HOP A UNIVERSAL LANGUAGE?

You might have heard the idea that music is a universal language, but this is not really true. Different cultures have very different ways of making music, which – just like languages – take time to understand. This is a common pitfall for social music projects: if they impose a certain type of music, participants might feel their own musical traditions are being ignored.

For some, hip-hop is a potential solution to this problem of ‘global’ versus ‘local’. Hip-hop is played and produced in almost every corner of the globe and is easily adapted to different places – partly through lyrics, and partly through sampling. In Mexico City, there is a thriving and varied hip-hop scene, and rap battles are big business. Andrew has been investigating the relationship in the city between rap and violence.

WHAT IS HIP-HOP TRANSFORMACION?

Mexico City has a crime problem, partly because many people – especially young men – are involved with drug trafficking gangs that use violence to assert their power. Hip-Hop Transformacion is a project that aims to improve this situation through music competitions.

Participants in Hip-Hop Transformacion are required to write rap lyrics that promote peace, and attend workshops about violence. In the workshops, they watch videos, reflect on their own backgrounds, and meet academics and rappers to learn about conflict and alternative ways of life. They then compete to win prizes including studio time and money.

HOW SUCCESSFUL HAS HIP-HOP TRANSFORMACION BEEN?

Andrew says the main thing he has found is “just how complicated it is to try and effect change”. One of Hip-Hop Transformacion’s recent competitions (called Rappers for Peace) asked rappers not to write lyrics that could incite violence, drugs or discrimination, but these things are often part of people’s daily lives in Mexico. This meant the rap lyrics had two sides to them: the positive messages delivered in the programme’s workshops and the references to the reality of living in conflict.

Hip-Hop Transformacion has drawn attention from and inspired some participants to pursue a career in hip-hop. Andrew wonders, however, whether “the people who won the competitions might have been more likely to follow this path to begin with”.

MEET ANDREW

I always listened to music and got more into making music as I got older. Being able to make a living through doing research with people who make music is wonderful.

I spent four months in Mexico just after finishing school and fell in love with the country. I was there as a volunteer and spent a lot of time giving children music lessons in an informal settlement – what some might disrespectfully call a “shanty town” – on the outskirts of Mexico City.

I listen to and write music for enjoyment, but also listen out for ways that music can open up different senses of social and political possibility. I listen to music to concentrate when I’m working, too.

There is evidence that the arts can work to promote peace, although there are often claims made about the arts and social transformation that aren’t borne out, as in the case of El Sistema in Venezuela. El Sistema is a publicly financed music-education programme founded in 1975 by musician and activist Jose Antonio Abreu.

Among other things, El Sistema claims to provide Venezuela’s most vulnerable children a way out of their impoverished lives, but research by Professor Geoff Baker, an academic in the Department of Music at Royal Holloway, University of London, UK, called into question many of its claims: www.theguardian.com/music/2014/nov/11/geoff-baker-el-sistema-model-of-tyranny

It’s important to have effective, grounded research on arts programmes. I’m attracted to the idea that responses to social problems can be inherently meaningful, fun and life-affirming, as well as providing solutions to social problems. This is what socially engaged arts programmes promise, if they’re carried out well.

The Gap Between Rhetoric and Reality

Dr Gillian Howell is a research fellow in the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music at the University of Melbourne, Australia. She is interested in the difference between how social music programmes report their success, and how well they really achieve their aims.

WHY DO SOCIAL MUSIC PROJECTS NOT ALWAYS GO TO PLAN?

In 1997, Gillian was in the back of a United Nations minibus heading to Vukovar in Croatia, a town physically and socially destroyed by multiple recent wars. Her mission was to play in a concert, to bring an evening of musical entertainment and connection to the inhabitants who had been through so much trauma. When Gillian and her colleagues arrived, however, they found their audience were almost all international aid workers, instead of from the local community.

For Gillian, the experience was a personal example of social music not going to plan, despite everyone’s best intentions. By their very nature, these projects target places where communication and trust are difficult to establish, and there are many competing sources of power. This makes for unpredictable project spaces where things rarely go as expected.

WHY DO REPORTS TEND TO FOCUS ON THE POSITIVES?

When she returned home from Vukovar, Gillian was reluctant to see the trip as a failure. After all, she and her fellow musicians had done what they had promised and felt it could have been a worthy contribution. So, when she told people about it, she focused the story more on what the musicians had set out to achieve, rather than what had actually happened.

Focusing on the positive side is a natural thing to do when things do not fit a neat storyline, but there is also pressure from others to paint a rosy picture of social music projects. Funders, for example, look for success stories when allocating money, meaning that admitting failures could lead to fewer opportunities in the future.

WHAT DOES IT TAKE FOR A PROJECT TO BE SUCCESSFUL?

Gillian points to a few reasons why music can be an effective tool for social projects, such as the fact it creates relationships between musicians, and that can be used to express complicated emotions. “Art can be used to represent an idea without making it explicit,” she says. “This can help you to explore or express difficult ideas that you may not have words for.”

Gillian’s research has shown, however, that the success of a music project is mostly about everything that surrounds the music activity. For example, a project needs a well-structured teaching plan; a community that is welcoming external input; a long-term plan; and engagement from lots of committed people.

MEET GILLIAN

We live in an age where the group of people who get to be music-makers and consider themselves musical is getting smaller and smaller. The rest, a much larger group, many of whom call themselves “unmusical” or “tone deaf”, are the consumers of music. It is my life’s mission to challenge this narrative whenever I can!

After all, human beings are built for music. Our bodies are filled with pulse, rhythm and musical potential. They give us feel-good rewards like dopamine when we engage with music. Our voices have the capacity to be huge – on our own and together with others. I would like to see teachers and students challenging the idea that music is only valuable if it is perfect and ready for consumption.

Music is so much more than something to be consumed. It is one of the ways we make sense of the world, and a way that we connect with others and build community. To do that, we need to truly celebrate all musical sounds. We need to love the sound of music learning and embrace the full journey from beginner to expert. And we need to take deep breaths, fill our lungs, and transform it into glorious, unapologetic sound.

A Journey Through the Senses

Professor Gloria Zapata-Restrepo is the UNESCO Chair in Arts, Education and Culture of Peace at Juan N. Corpas University Foundation, Colombia. She has been finding out how the programme Expedición Sensorial is revitalising traditional Colombian culture in places affected by conflict.

WHY DID THE MONTES DE MARIA FALL SILENT?

Near the northern coast of Colombia, there is a remote mountainous region called the Montes de Maria. Its history has been marred with violence since the arrival of European colonisers in the 16th century, bringing with them weapons and diseases that nearly wiped out the Indigenous population. They also brought slaves from Africa to a nearby port, some of whom managed to escape into the mountains.

Despite this, the Montes de Maria developed its rich cultural traditions, until drug-related conflict brought more tragedy to the region. Since 1995, more than half of the population were displaced, and in a campaign of terror between 2000 and 2002, the names of many towns became infamous around Colombia for the massacres that took place there. Growing up in a world of fear, the young people did not learn to sing and dance.

WHAT IS EXPEDICION SENSORIAL?

The Colombian Ministry of Culture set out to try and rebuild the culture of the Montes de Maria through a programme called Expedicion Sensorial, which Gloria describes as “a journey through the senses, or an exploration of diverse cultural and arts practices”. Since it began in 2016, over 5,000 people across the region have taken part.

The aim of the programme is to help people reflect on the conflict and create new, peaceful bonds in communities. It does so by bringing young and old together to learn traditional dances or instruments such as the kuisi – a type of flute that is made from a hollowed-out cactus stem and sounds something like an alto recorder. In each village, the programme is delivered by a local teacher.

IS IT DANGEROUS TO BE A TEACHER FOR EXPEDICION SENSORIAL?

Although a peace deal was signed in 2016, Gloria says there is still a risk of violence in the Montes de Maria, and social leaders are often targeted. One teacher said they once received threats: “Letters arrived to three colleagues at the schools where they worked, saying that if they were seen again in the area, then they would be killed”.

The teachers do it, though, because they see the benefit of their work. They feel that the music itself is not the end goal, but that the process of learning music helps improve people’s lives. One teacher explained, “For me it’s not about forming great artists, but forming great people.” Another teacher said, “Our focus was’t to train people to become professional musicians, but to heal the wounds that they received during the armed conflict.”

MEET GLORIA

When I was younger, I wanted to be an artist and a scientist. My relatives and friends helped inspire me to study arts and education, but given the need for social changes in Colombia, I also felt it was crucial for me to work in peace studies.

Music is essential and is life itself. I believe arts and culture always give possibilities for change. Every little cultural or arts activity could make the difference for an individual or a community.

A World of Sound

Professor Lukas Pairon is the founding director of Social Impact of Making Music (SIMM), an international research platform based in Belgium. He has been studying social music projects in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

WHO ARE THE ‘WITCH CHILDREN’ OF KINSHASA?

One of the social music projects Lukas studied was Espace Masolo – a centre for young people who ran away from their families as children. They left to live on the streets after being accused by their families of being ‘witch children’. This happens when parents believe evil spirits have entered the child and cause bad things to happen such as poverty and illness.

At Espace Masolo, the young people are looked after and given the chance to learn wind instruments, percussion, sewing and theatre.

Many are also helped to reunite with their families. The aim is for the participants in Espace Masolo to build confidence through their art and learn they are not ‘witch children’ but valued members of society.

WHY WAS LUKAS SCEPTICAL OF SOCIAL MUSIC AT FIRST?

“If music could bring peace, peace would be everywhere” says Lukas. When he set out on his research in Kinshasa, he felt that it was far too simplistic to suggest music on its own can resolve conflict. Claims about the “magical power” of music to “save lost souls” were all too romanticised, he thought, and not well founded in evidence. This prompted him to spend many months living in Kinshasa to try and understand the role music was playing there in social and community work.

CAN MUSIC MAKE US MORE OPTIMISTIC?

Lukas stands by the fact that music on its own cannot solve complex issues of poverty and violence, but he has found that it can transform the way people think. In Kinshasa, joining a project such as Espace Masolo will not create new job opportunities, for example, and its participants are unlikely to make much money as musicians. It can, however, lead people to a more positive outlook on their situation.

The young people Lukas talked to told him that learning music took them into a whole new “world of sound”, in which they experienced freedom. This freedom was in contrast to the harsh barriers they faced in day-to-day life due to poverty, but it made them more resolute to make the most of what they had. Lukas has coined this capacity ‘positive fatalism’. As he describes it, “positive fatalism is the capacity to embrace the reality you are living in, including its limitations, allowing you to focus your talents and means on developing projects which are possible within that reality.”

MEET LUKAS

Caption: © Music Fund

I did not have a clear idea about what I wanted to be when I was younger, but I wanted to study and be involved in the world of music. I was interested in educational science, being active working with small children in the local youth movement.

I wanted to study different human sciences. In secondary school I learnt about the philosopher Martin Buber and this inspired me to learn philosophy.

SIMM is an international network of scholars developing research on the role music may play in social and community work. The aim of this field of research is to come to a better understanding of social music programmes, so that practitioners can learn from the research findings and improve their practice. Although I am cautious not to overstate it, I do think that music and art can play a role in inclusion and peace education.

A Little Ray of Hope

Professor Patricia A. González-Moreno researches music and music education at the Autonomous University of Chihuahua, Mexico. She is the President Elect of the International Society for Music Education for the biennium 2022-2024. Patricia has been analysing the role of music in supporting children and their families in the state of Chihuahua.

WHY IS MUSIC EDUCATION IMPORTANT IN CHIHUAHUA?

While the word Chihuahua might make you think of a very small dog, the state of Chihuahua is the largest in Mexico, covering an area greater than the UK. Unfortunately, it is also one of the most violent, with high crime rates fuelled by illicit drug imports into the USA.

In this region, dominated by rival gangs and cartels, the rest of society needs to work hard to make sure everybody has a good start to life. That is why there are multiple cultural programmes in the state helping to deliver music education to young people. Their aim is to provide a safe space for socialising and provide an alternative to risky behaviours out on the streets.

One example is Umbral, Construyendo Comunidad, A.C. which Patricia has studied in detail. Children are invited to join symphonic bands, choirs and traditional music groups such as mariachi bands. Parents are allowed to join too, or often work to support the programme, helping to build a sense of shared community purpose. Patricia has also been studying the Nucleo Comunitario de Aprendizaje Musical (NUCAM) programme in Quinta Carolina. Here, too, parents can take part by joining the adult choir or guitar ensemble.

HOW DOES MUSIC PROVIDE HOPE TO YOUNG PEOPLE?

For some young people, joining a music group was one of the few ways they felt safe and secure. Patricia interviewed teachers and found they were very aware that some of the students needed emotional support. One Umbral teacher said, “The programme became a little ray of hope to these young people who are sometimes lost in complicated situations of drug addiction, violence, depression, family issues or sexual violence; they come to our orchestral programmes seeking emotional support as much as anything.”

Patricia thinks that because the programmes provide a safe space, they help children to understand who they are and what they are good at, as well as making them more aware of their role in society. She acknowledges that music programmes will not stop the violence but says they “contribute to the participants’ well-being and their communities by reinforcing social skills and cooperative behaviours”.

Based on her observations, Patricia feels both Umbral and NUCAM are worthwhile social music projects. “The programme leaders, coordinators and music teachers are all aware of how important it is to build cultures of peace,” she says. Over 250 children were enrolled in Umbral 2020, for example, but as Patricia says, “it is difficult to evaluate how successful a programme is simply in terms of participation when those efforts can have a larger social impact that is difficult to measure”.

MEET PATRICIA

As a kid, I loved music, however I was not sure what I wanted to be. In primary school, I occasionally had music lessons, and as a teenager I took voice lessons. It was after studying computer sciences for two years that I changed my major, convinced that I wanted to follow my interest and passion for music.

Like any other music student, I wanted to be a professional musician, but along the way I acknowledged how important music teachers are. I felt passionate about music teaching and decided to apply for a PhD in the United States. I was fortunate to be accepted at the University of Illinois where I had guidance from Professor Gary McPherson. He was a great mentor and role model, and he inspired me to become a researcher in music education.

My goal is to make music learning available to others by teaching those pursuing a music career, and through teaching future music teachers and researchers. Music should be available to those who have less opportunities. Music and the arts are a human right, not a privilege for just a few. For this reason, I want to express my deep appreciation for the work that everyone involved in these programmes does to make this possible for the kids they work with, their families and local communities.

Stories of Sanctuary

Dr Sam Slatcher is Director of Citizen Songwriters in the UK. He has been working with a project in the northeast of England that aims to bring diverse communities together through songwriting.

WHAT IS PARTICIPATORY SONGWRITING?

Sam was a facilitator for ‘Stories of Sanctuary’ in the city of Durham, UK. The project was designed to forge connections between refugees and more settled residents, in a part of the country where tensions over immigration are high. It did this by helping the community to write songs together.

The idea of participatory songwriting, as it is known, is to make sure everyone’s voice and perspective is included in the song. Sam says, “It works best when everyone has a chance to input their ideas and is involved in the shaping of the song.” He thinks it is a good tool for community building because it allows people to connect emotionally, something that is difficult to do by talking.

In one workshop, a refugee called Kareem shared the story of how he fled his home in Damascus, Syria. He was 16 years old and travelled alone. He recalls the sight of his shadow against the moonlight hitting an empty road and feeling very alone. After listening to the story, the group started to form the lyrics of a song, with Sam suggesting chords on his guitar to fit the mood.

They wrote:

“Shadow, where are we going tonight?

As you grow, and outrun those searching lights

Somewhere alone in the Serbian snow

All I know, yellow line on the road

Oh Shadow, it’s only you and I around.”

Although the song was based on Kareem’s personal story, the other participants felt they all contributed. Eliza, another participant, said, “The song was very organic, with many pieces coming together. It emerged out of people reacting to his story, plus the melody and the singing.”

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM STORIES OF SANCTUARY?

Sam says that Stories of Sanctuary was a success because a lot of work was put into encouraging people to take part, understanding the needs of the local community, and taking a creative approach to the songwriting itself. He hopes that his contribution to TAI highlights how he, as a facilitator, “found an opportunity to use music to encourage conversation, points of empathy, connections between people, cultures and ideas”.

Participatory songwriting could become more popular in the future. Sam says that it is an attractive approach to social music because it can have a big impact on the communities that take part, and helps to break down the perception that music making is only for professionals.

MEET SAM

I wanted to be an airline pilot when I was younger so I could explore the world. How different my life looks now! With her passion for the world, social causes and the environment, my geography teacher at school inspired me to study geography.

I set up Citizen Songwriters in 2018, and we have worked closely with 12 local communities across the UK. We have contracted freelance musicians, worked in partnership with local authorities, recorded community group projects and performed in public more than 20 times. For a small organisation with one full time and one part-time staff member, I think we punch above our weight!

As well as paying the bills, music is my first love. I always carry my guitar around with me in the same way dog owners take their dog for a walk. It is my form of meditation when I walk and play guitar on the move.

Music stirs our emotions, prompts us to act, helps us laugh and cry and, ultimately, helps us connect with and understand each other. As I write, I hear on the radio they are hoping to release John Lennon’s “Give Peace A Chance” with the video including 100s of communities singing the song across the world standing in solidarity with Ukraine. I think that says it all!

Music For All

Professor Sergio Figueiredo is a former associate professor at State University of Santa Catarina, Brazil. He has been asking if music education for all can help to create well-rounded citizens.

WHAT IS MUSIC EDUCATION LIKE IN SANTA CATARINA?

The Brazilian state of Santa Catarina has a strong economy and little poverty compared to other parts of the country, but there are still some areas that do not have the same opportunities as others. While music is part of the national curriculum, it is not well-funded and many schools only have one teacher to cover all types of art. Stepping in to fill this gap are social music projects. Sergio has been studying two in particular: Porta do Sol and Bairro da Juventude, which he says “offer opportunities for musical and social development to children and teenagers in vulnerable situations”.

ARE GOOD ARTISTS GOOD CITIZENS?

The aim of the Porta do Sol project was to combine music education with general citizenship. Alongside musical activities, the young people involved were encouraged to interact socially, respect each other’s differences, and work as a team. Bairro da Juventude also teaches musical cooperation, by running choirs and instrumental groups. “Music is an aggregating activity, which brings people together and awakens a sense of coexistence, respect and collective work,” says Sergio.

HAS SOCIAL MUSIC IN SANTA CATARINA ACHIEVED ITS AIMS?

Sergio has spoken to teachers on the social music programmes who have seen transformations in the children they worked with. To begin with, many children struggled to get on with their peers and behaved inappropriately, but they became calmer and more responsible over time. Some former students of Porta do Sol have even gone on to have careers in music.

Sergio feels both Porta do Sol and Bairro da Juventude have shown the importance of music. Instead of complaining about the failure of the state to provide it, they got on and did the job successfully, helping – even if in a small way – to form a “fairer and more humane society”.

MEET SERGIO

I decided very early on that I would like to be a musician. I studied piano and cello for many years and then dedicated myself to choir conducting. I wanted to be a musician, but to earn money, I started teaching in music schools.

I found it interesting to follow the students’ musical development. This led me to research laws and public policy about music education. I believe all those who go through school should have opportunities for musical training, and I hope my research can help to provide that.

Music has been part of my life for many years. Even as a university professor and researcher, I regularly conducted choirs. For me, making music reiterates the importance of this activity. I believe that music has provided experiences that allow me to understand different aspects of being human. Music enriches my life and I always want to share what I have learned.

I think the arts offer important avenues for inclusion and peace education. I am quite convinced that the presence of the arts in social programmes can bring benefits, both for those who receive artistic teachings and for those who teach. And, certainly, the impact is greater when shared with society in concerts, shows, exhibitions or music courses, for example. I increasingly believe that social music programmes are having positive results, contributing to the quality of life in society in general.

Visit the TAI website to uncover the stories of other TAI members, including Alberto Cabedo-Mas, Daniel Mateos-Moreno, Deanna Yerichuk, Geoff Baker, Hector Vázquez, Jenny Scharf, Leeanne O’Hara, Liam O’Hare, María Elisa Pinto, Mo Hume, Oscar Valiente, Ruben Carrillo, Santiago Niño, Shelly Coyne and Valeria Gascón: www.tai.international

Do you have a question for the TAI Network?

Write it in the comments box below and the TAI Network will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

DEARS,

Your works looks to be beautiful and it seem to me to have a lot of potential worldwide.

I’m writing a psychology thesis on how music and art can be a vehicle for reducing conflicts intra and inter communities. However, i’m looking for evidence bases practice that can confirm it.

I would like to ask you if you have or know publications like that and if you can share it to me.

Hoping that we can meet and share some time together one day I leave my sincere regards,

ALBERTO PENNELLA

Thanks for your query Alberto, you could start browsing the articles in the recent Special Issues of the journals Musicae Scientiae (Bartleet and Pairon, 2021), Frontiers in Psychology (Hansen et al., 2022) and Journal of Music, Health, and Wellbeing (Williams et al., 2021). I reviewed some of this literature in articles in Mental Health and Social Inclusion (2023) and British Journal of Music Education (2018), pre-print versions of which are available at the University of Glasgow repository at http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/view/author/29541.html. I hope this helps! Kind regards, Oscar Odena