Can spooky stories engage people with history and heritage?

The English countryside is littered with the crumbling remains of ancient abbeys and priories, many of which are supposedly haunted. Professor Dale Townshend, from Manchester Metropolitan University, UK, and Dr Michael Carter, from English Heritage, have previously investigated how the Gothic architecture of these medieval ruins inspired Gothic literature in the 18th and 19th centuries. Now, they and their team, including Dr Dominique Bouchard, are using tales of the supernatural to engage the public with these heritage sites.

Talk like a Gothic scholar

Gothic architecture — a medieval building style commonly used for religious buildings between the late 12th and early 16th centuries, characterised by pointed arches and ornate carvings

Gothic literature — a writing genre associated with horror, fear and the supernatural

Heritage — historic sites of cultural significance

Medieval — the 5th to 15th centuries, often referred to as the Middle Ages

Purgatory — a state of existence after death where souls must wait to be cleansed of sin before entering heaven

Reformation — a time of religious and political upheaval in the 16th century when the authority of the medieval Church was challenged, leading to a permanent division in Christianity between Catholicism and Protestantism

Revenant — a corpse that rises from its grave to haunt the living

Supernatural — used to describe something that seemingly defies the laws of nature, such as ghosts

Theological — relating to the study of God and religion

Stumbling out of the twisted undergrowth, you stare at the crumbling stone building that looms out of the shadows. Amidst fallen archways and toppled pillars, huge wooden beams lie decaying in the cold mud. A damp mist seeps from the cracked walls and lingers like a stagnant pool around the ruin. You rush through the rotting wooden doors that hang crooked on their hinges, and they creak slowly shut behind you. Heart racing, you stare around the dark ruin. You’re just beginning to collect yourself when a ghostly hand suddenly grips your arm…

Whether huddling around campfires, cowering under blankets or hiding behind sofas, humans have always had a strange fascination with ghost stories. Today, they are told to frighten and entertain, but in the past, they were used to inform and educate listeners about beliefs of life after death.

What can we learn from ghost stories?

“In the medieval period, ghost stories were often told and written down by monks,” says Dr Michael Carter, a historian at English Heritage. “These tales aimed to illustrate the progress of the soul in the afterlife, and the importance of praying for the souls of the dead on their passage from purgatory to heaven.” Ghosts were thought to be souls in purgatory, waiting to be cleansed of the sins they had committed during life. Ghostly tales encouraged people to pray for these lost souls so they could continue their journey to heaven. “Ultimately, medieval ghost stories served moral and theological functions that showed the importance of preparing for death and the value of ‘good works’ such as saying prayers for the dead and distributing charity,” explains Michael.

How did medieval ruins inspire Gothic literature?

As time passed, the religious landscape of England changed. With the Reformation, Protestantism replaced Catholicism as the dominant religion, Catholic ideas of purgatory were abandoned and monasteries were forcibly closed. After centuries of neglect, these grand abbeys and priories fell into disrepair, remaining only as symbols of death, decay and the supernatural.

During the Georgian and Victorian periods (1714-1901), these ruins of Gothic architecture became perfect settings for a new generation of ghostly tales, and the genre of Gothic literature was born. Characterised by an atmosphere of fear, suspense and the supernatural, Gothic literature is the realm of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) and Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897).

“Gothic literature was merely the continuation of ghostly, supernatural storytelling traditions that reached back to the medieval period,” explains Dale Townshend, Professor of Gothic Literature at Manchester Metropolitan University. “Numerous Gothic writers of the 18th and 19th centuries set their novels and poetry in ruined religious houses. In doing so, they offered readers vivid and nightmarish visions of the ancient Catholic past that was imagined to have played itself out in these buildings.”

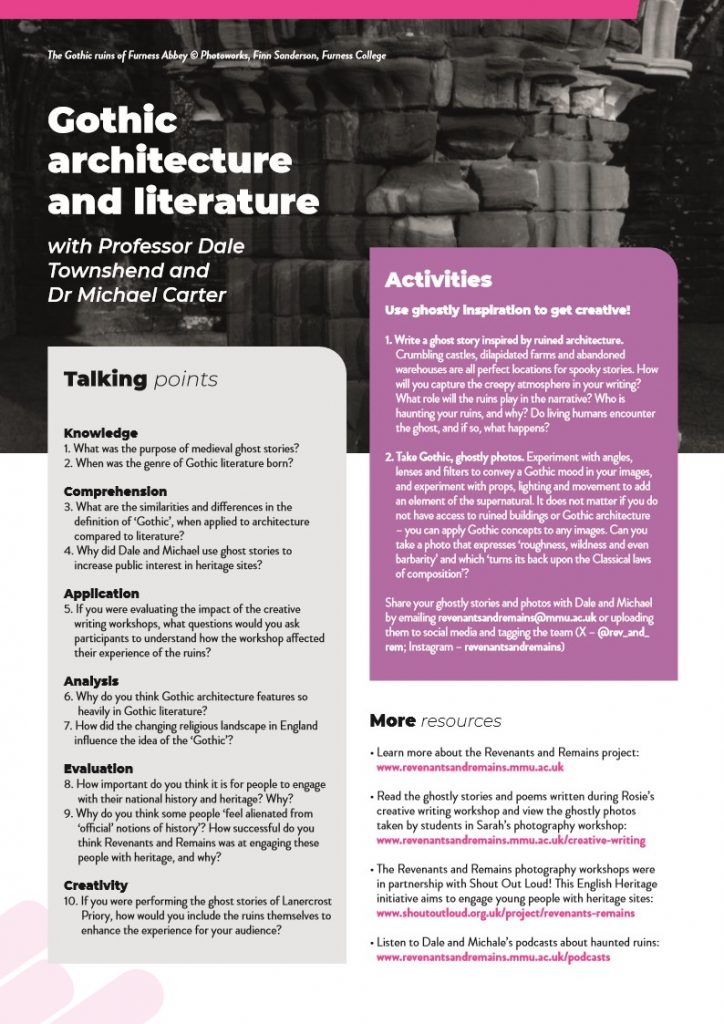

How can ghost stories engage people with heritage?

Dale and Michael believe that the enduring appeal of spooky stories can capture the public’s imagination. Using tales of ghosts who haunt religious ruins in the north of England, they are inspiring people to engage with English history and heritage. “We wanted to discover how we might employ the Gothic imagination to enrich modern-day experiences of ruined architectural heritage,” explains Michael. “We hope that our project engages audiences who might otherwise feel alienated from ‘official’ notions of history.”

Dale and Michael’s Revenants and Remains project took place at five religious heritage sites associated with the supernatural. For example, at Rievaulx Abbey, 12th-century monks were terrorised by a demonic visitor; numerous 14th-century tales tell of bloated corpses rising from the graves at Lanercost Priory to torment the living; and Ann Radcliffe, a famous 18th-century Gothic writer, imagined the ruins of Furness Abbey to be populated by ghostly friars.

Using ghost-themed guided tours and a series of creative workshops led by professional artists, Revenants and Remains aims to enhance the experience of tourists visiting the ruins through the lure of the supernatural.

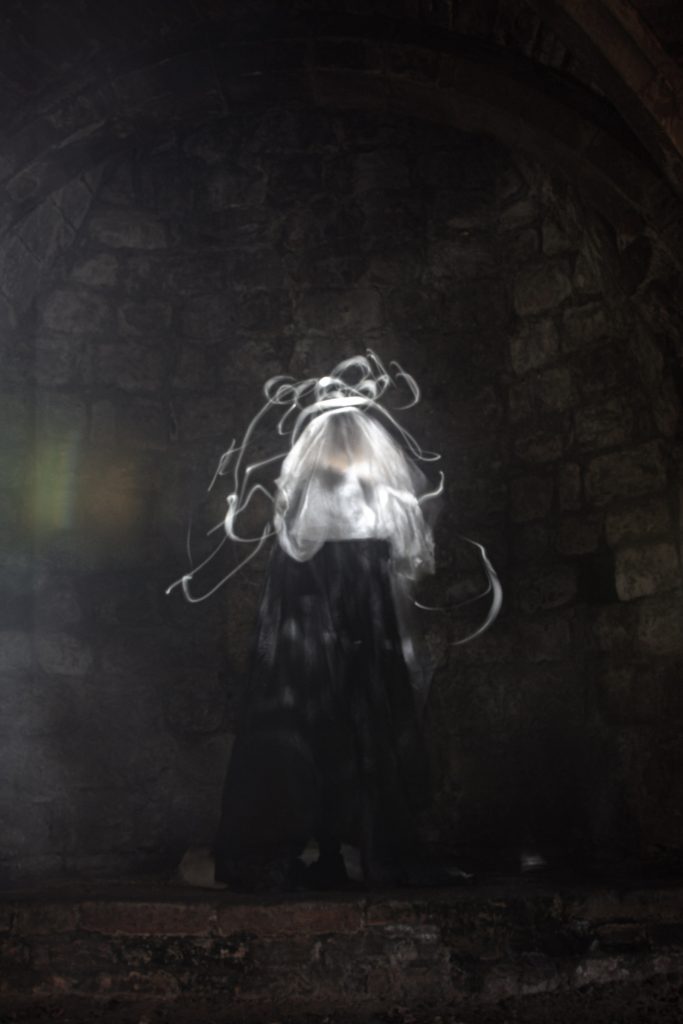

Rosie Garland, an award-winning novelist, led creative writing workshops at each of the sites. “In the same way that these Gothic remains inspired writers in the 18th and 19th centuries, Rosie encouraged participants to respond creatively and imaginatively to the ruins, and to create their own interpretations through the guiding lens of the supernatural,” says Dale. Actor Robert Lloyd Parry performed M.R. James’ chilling ghost tales within the ruins themselves. “Robert’s performances brought the stories of each haunted location vividly to life, while highlighting the links between Gothic architecture and supernatural storytelling for a pleasurably terrorised audience,” says Michael. And artist Sarah Sparkes, working with Photoworks, led photography workshops for local students, who were supported as they created their own ghostly photographic interpretations of the ruins and tried to convey a sense of the supernatural within their images.

How have people responded to the project?

“We’ve been nothing less than delighted by the response to the project!” says Michael. Drawing on Gothic and ghostly themes allowed visitors to discover aspects of the ruins that are rarely included in traditional histories, and participants commented on how the use of the supernatural increased their interest in the site’s history.

“The Gothic mode has proved to be a particularly effective means of engaging young people in history and heritage,” continues Dale. “As the photographs, poems, short stories and other creative outputs from the workshops indicate, the potential for ruins to inspire writers and artists today is as powerful as it was in the 18th and 19th centuries.”

Professor Dale Townshend

Professor Dale Townshend

Professor of Gothic Literature, Department of English, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK

Field of research: Gothic literature

Dr Michael Carter

Senior Properties Historian, English Heritage, UK

Field of research: Architectural history

Research project: Using ghost stories to increase public engagement with English heritage sites

Funder: Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC)

About Gothic architecture and literature

What defines Gothic architecture?

“In architecture, the term ‘Gothic’ initially implied that something was medieval and characterised by a certain roughness, wildness and even barbarity,” explains Michael. The primary features of Gothic architecture (such as pointed arches, vaulted ceilings and flying buttresses) did not conform to the rules of Classical architecture from the Greek and Roman periods, which stated that buildings must have strength, utility and beauty. “Gothic architecture was seen as a systematic violation of the Classical ideals of symmetry, balance and proportion,” says Michael. “And, in Protestant England, Gothic architecture was associated with Catholicism and its perceived primitiveness and cruelties.”

What defines Gothic literature?

“In literature, the term ‘Gothic’ was used to describe a style of writing that turned its back upon the Classical laws of composition and which was associated with irregularity, roughness and imaginative excess,” explains Dale. “One constant within this genre is a preoccupation with a dark and barbaric Gothic past that is characterised by a belief in the supernatural, to the extent that the term ‘Gothic’ itself came to serve as shorthand for the supernatural literature of horror and terror.”

How can the ‘Gothic’ promote an interest in heritage?

As the Revenants and Remains project proves, there are many creative ways to engage people with history and heritage. Michael is an art historian who specialises in the architecture of monasteries in the north of England, while Dale is a literary critic with expertise in Gothic writings of the 18th and 19th centuries. “By combining the history of English ruins with insights from Gothic architecture and literature, we believe that our project has provided an exceptionally rich and illuminating approach to engaging people with English heritage.”

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM458

© Photoworks, Sophie Waldron, Newcastle College

© Photoworks, Amy Johnstone, Newcastle College

© Photoworks, Amanda Stacey, Newcastle College

© Photoworks, Anna Cumberbatch, Furness College

During photography workshops at Lanercost Priory, students experimented with lighting and movement…

© Photoworks, Theo Young, Newcastle College

© Photoworks, Charlotte Beck, Newcastle College

© Photoworks, Jordan Hodgson, Newcastle College

© Photoworks, Sarah Campbell, Newcastle College

Pathway from school to Gothic studies

• At school, Gothic literature may be introduced in English literature classes, while elements of Gothic architecture may be covered in art and design classes. It would also be useful to study history to learn about the historical contexts in which Gothic architecture and literature arose.

• At university, a degree in English literature, creative writing, architectural history, art history or history could be tailored to focus on Gothic elements.

• “Read voraciously,” advises Dale. “Read Gothic fiction, such as Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847) and Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847). As you read, reflect on the role that architecture, either ruined or unruined, plays in the narrative.”

• In addition to reading, watch horror films and TV shows and consider how they rely on age-old associations between Gothic architecture and a sense of fear.

• Visit heritage sites or ruins and respond creatively. “What story would you set there, and what role will the ruins play in your narrative?” asks Michael.

Explore careers in Gothic studies

• A career in Gothic architecture could involve studying the historical significance of medieval ruins (like Michael) or preserving them so future generations can explore their heritage. Learn more about the work of English Heritage: www.english-heritage.org.uk

• Similarly, a career in career in Gothic literature could involve studying Gothic texts (like Dale) or writing or performing them (like Rosie and Robert). Learn more from the Manchester Centre for Gothic Studies: www.mmu.ac.uk/english/gothic-studies

Meet Dale

I’ve always been fascinated by the supernatural, and my earliest choices in literature reflected this. Despite being terrified by the prospect of the supernatural, I was strongly drawn to ghost stories as dark sources of pleasure. I now make a living from studying and teaching the material that excited me as a young boy.

My greatest sources of inspiration have been the mentors who have taught me English literature over the years, from primary school through to postgraduate university research. Literature has the potential to change lives, and those who teach it occupy a privileged position of responsibility and influence. I am still inspired by my past tutors who taught me how to love and appreciate all forms of literary expression. I also thrive on the research-related aspects of the job, and enjoy the challenge of tracking down rare facts, documents and manuscripts in archives and libraries around the world.

The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), by Ann Radcliffe, is my favourite Gothic novel. Though she is not well known today, Radcliffe was one of the most successful Gothic writers of the 18th century. I love the story’s preoccupation with Gothic architecture, especially the partly ruined and supposedly haunted castle in Italy that gives the novel its title.

It has been very rewarding to see the public’s response to our Revenants and Remains project. I was particularly gratified to see how young people created their own fresh photographic interpretations of ruins through the lens of the supernatural. The Gothic certainly has the power to engage those who otherwise might feel alienated from national history and heritage.

Meet Michael

My love of the history and architecture of monasteries was inspired by my Catholic upbringing and childhood visits to the ruins that populate the landscape of Yorkshire. These stirred my imagination and touched my soul.

I first encountered the ghost stories of M.R. James in my early teens, which contain elements of the medieval past, such as ruined monasteries. At school, I also studied Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose (1980), a Gothic novel set in a 14th-century abbey which provides fascinating gleanings about life in medieval monasteries.

After studying history at university, I got a job in the civil service. I spent almost 20 years writing patient information literature for gay rights organisations and HIV charities, which taught me many valuable skills, such as the ability to communicate with non-specialist audiences. At the age of 41, I decided to explore my true passion, so I returned to scholarship and started a PhD studying the art and architecture of medieval monasteries in northern England.

Kirkstall Abbey is my favourite Gothic ruin. Not only can you see how the architecture of the monastery developed between the 12th and 16th centuries, but the well-preserved ruins also provide a valuable source for charting how life in a monastery evolved over time. From an academic perspective, the ruins bring the life of medieval monks alive. From a personal perspective, my grandfather was the custodian of Kirkstall Abbey and I have many memories of childhood visits to the ruins. The ruins even have a ghost story – the last Abbot died heartbroken, and his spirit now haunts the Abbey museum!

Do you have a question for Dale and Michael?

Write it in the comments box below and Dale and Michael will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

By abolishing the Catholic church in England, King Henry VIII was responsible for many Gothic buildings falling into ruin. Learn more about the life of this (in)famous English king:

www.futurumcareers.com/what-happened-when-henry-viii-went-on-tour

0 Comments