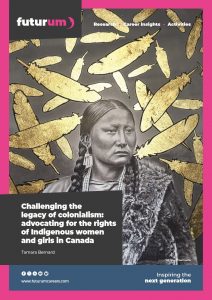

Challenging the legacy of colonialism: advocating for the rights of Indigenous women and girls in Canada

In Canada, Indigenous women face disproportionately high levels of violence and are greatly overrepresented in long-term and unresolved missing person cases. At Lakehead University, Tamara Bernard is researching the systemic discrimination that takes place against Indigenous women and girls, with the goal of creating a safer and securer world for them in the future.

Talk like an … Indigenous advocacy researcher

Advocacy — the act of supporting something publicly

Anishinaabekwe — a woman from the Anishinaabe, a group of Indigenous Peoples in the Great Lakes region of Canada

First contact — when colonists first made contact with Indigenous People in Canada (from Greenland and Iceland in the 11th century and from Europe in the 15th century)

First Nation — a term for the Indigenous People of Canada

Genocide — the intentional killing of a people or ethic group

Indigenous — the original people who lived in a land before the arrival of colonists

Systemic discrimination — ongoing biases that are embedded within a society and cause the unfair treatment of certain individuals

For centuries, the legacy of colonialism has dehumanised and perpetuated harmful stereotypes of Indigenous women and girls,” says Tamara Bernard (Shining Eagle Woman), an Anishinaabekwe and PhD candidate in education at Lakehead University. “As a result, and as highlighted in a 2019 national inquiry, Indigenous women and girls in Canada are 12 times more likely to experience violence compared to non-Indigenous women.”

Tamara’s connection to the issue of violence against Indigenous women and girls goes beyond the academic or her career. In 1966, her great-grandmother, Jane Bernard, and cousin, Doreen Hardy, were murdered. Both cases are still unsolved today. Tamara’s commitment to Indigenous advocacy is motivated by the need for both social and personal justice – for her family and community members. Realising that all she ever learnt about her great-grandmother was that she was murdered, Tamara believes deeply that Indigenous women and girls need to be recognised beyond the labels of ‘missing’ or ‘murdered’.

Gaps in the data

Before the national inquiry took place, government data from 1980 to 2012 highlighted that 1,181 Indigenous women and girls were killed or had disappeared within the 32-year timespan covered.

Tamara challenged the span of these government data: what about the women and girls who were killed or disappeared before 1980, like Jane and Doreen, or since 2012? Their stories need to be heard, and Tamara was determined to ensure they were. She wanted stories, not just statistics. She wanted to breathe life into the numbers.

The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) took place from 2016 to 2019. “Even after this long overdue inquiry, there continues to be gaps in the data,” explains Tamara. “Due to a lack of systemic national data collection, underreporting of cases, and challenges in identifying Indigenous victims due to insufficient racial data collection by police, these gaps mean that the crisis of violence against Indigenous women and girls in Canada in still not fully understood.”

The colonial legacy

“The violence targeting Indigenous women is deeply rooted within colonialism, racism, sexism, systemic discrimination and genocide,” says Tamara. In fact, the MMIWG report recognises that since first contact, the colonial legacy in Canada is one of genocide against Indigenous peoples.

An important aspect of Tamara’s work is highlighting how Indigenous women and girls are forced into vulnerable spaces by discriminatory mechanisms and policies. “Canada is the only country that has a piece of paper that polices and controls a certain demographic based on race,” says Tamara. That paper is the Indian Act – a legislation first passed in 1876, aspects of which are still enforced in Canada today.

The Indian Act sets the standard for how the Canadian government interacts with First Nation people. “The Indian Act is an aggressive, colonial piece of legislation that has forced many Indigenous women to lose their rights, identity and connection to their community,” says Tamara. Among other things, the act defines which First Nation people are given ‘Indian status’. Until it was amended in 1985, the sexist act declared that status women who married non-status men would lose their status, whereas status men marrying non-status women would not. “It is estimated that over 270,000 Indigenous women and their descendants are trying to regain their status rights and community ties,” says Tamara.

The missing or murdered Indigenous women who lost their status through the Indian Act are not included in the data highlighting crimes against Indigenous women and girls. “The flawed data downplays the impact that colonialism and its ensuing violence has had – and continues to have – on Indigenous women,” explains Tamara. To address ongoing injustices, all crimes against Indigenous women and girls need to be fully acknowledged – even if the women in question do not have official status.

Sharing stories

Part of Tamara’s work is focused on finding and sharing stories that challenge narratives of how Indigenous women are viewed and which honour them as individuals. “Personal stories and connections can reveal more than data,” explains Tamara. “Stories that challenge colonial ideas can humanise and bring hope, healing and empowerment. I want to show how Indigenous women continue to take up roles of leadership, like pursuing education, despite facing adversities.”

Tamara is using Indigenous research methods to gather these stories. “These methods are a collective experience where the researcher also shares their own stories to build relationships, connections and trust,” she explains. “For example, I have sat with Indigenous women and girls in many communities, groups and spaces, sharing parts of my own work and spirit.”

The stories Tamara gathers are co-edited with Indigenous Knowledge Sharers and Storytellers before being shared in articles, artwork, exhibitions and textbooks. One collection that Tamara coordinated, in partnership with CTV Bell Media and Atlohsa Native Family Healing Services, is an MMIWG Public Education exhibit called ‘See Me’. The first of its kind when it first took place in 2014, the project uses stories to honour Indigenous women and girls among MMIWG, beyond those represented in the data.

There is still lots to be done to create a safer society for Indigenous women and girls, but Tamara is passionate and determined in her work. “My aim is for Indigenous women and girls to feel seen, heard and reflected,” she says. “Because far too often, Indigenous women’s voices and representation are not at the table. I am pulling up chairs and inviting other Indigenous women to join me.”

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM642

Helpline

The Talk4Healing Helpline offers help, support, and resources 24/7 through talk, text and chat. It has provided over 30,000 Indigenous women and their families with real-world solutions, without judgement, in a safe and accepting environment.

Talk: Call 1-855-554-HEAL and live support will be there to listen, any time of day

Text: Send a message to receive support anywhere

Chat: Click on the live chat option and start a session.

Tamara Bernard

Tamara Bernard

PhD Candidate and Instructor, Indigenous Learning Faculty, Lakehead University; Advisor for Indigenous Research and Knowledge Systems, Creative Fire, Canada

Fields of research: Indigenous learning, trauma and gender-based violence, education

Research project: Advocating for Indigenous women and girls

Funders: Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC); Seven Generations Education Institute

About Indigenous learning

Indigenous learning combines ideas from history, sociology, geography and anthropology. It focuses on understanding the societal structures affecting Indigenous groups, the ongoing and complex impacts of colonial practices, and the creation of policies and spaces that might lead to a more equitable world.

An important part of Indigenous learning is championing different perspectives and voices. “The majority of our history books are written from non-Indigenous perspectives,” says Tamara. “And while we have some great ally faculty who have dedicated themselves to building trusting and holistic relationships with Indigenous communities, Indigenous faculty members and representation is still needed.”

What are the challenges of advocating for Indigenous women and girls?

“Since first contact, Indigenous women have been sexualised, treated as less human and traded like objects,” says Tamara. “Canada has a hidden history of slavery, and the majority of those enslaved were Indigenous women and girls.” For advocates like Tamara, the challenge is ensuring that ongoing violence is not minimised or ‘brushed under the carpet’. “Often, I witness no amber alerts being administered (to highlight an emergency situation) and a lack of participation when searching for missing individuals,” says Tamara. “When sharing risk assessments of concerns of intimate partner violence or human trafficking, I see frontline officials dismissing concerns.”

“I was often told that I cared too much, but there is a reason that Indigenous women and girls reach out to me privately to support their navigation of the system. The system is broken,” says Tamara. Tamara gives these women a voice, and many voices need to be heard if the system is to be fixed. She explains, “There is an invisible, heavy backpack that many Indigenous women carry, and I see it when I am in the community and when I’m teaching.”

What needs to be done?

A large part of working in this field involves engaging with members of the public, political leaders and community groups to provide education on systemic discrimination.

“We need more investment into Reconciliation Action Plans,” says Tamara. Tamara is an advisor for Creative Fire, a national Indigenous communications firm bridging the divide between Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups and facilitating Reconciliation in Action. “Creative Fire is advocating within multiple sectors across Canada to ignite social impact for Indigenous peoples, especially Indigenous women. Our work focuses on economic development, self-determination and Indigenous Peoples rights; it is about healing, empowerment, inspiration and hope.”

Long-term sustainable funding is also needed for Indigenous gender-based violence programmes and services. “We need to develop Indigenous informed and culturally grounded services, invest in and support Indigenous approaches, and foster decision making by Indigenous communities,” says Tamara.

Injustices

Injustices targeting Indigenous women can be seen in practices such as ‘birth alerts’. These alerts, which disproportionately affected Indigenous women, meant that hospitals could flag mothers they considered high-risk, for social services to seize their babies when they were born. Birth alerts were banned due to ‘Calls to Justice’ from the 2019 national inquiry, grounded from stories by Indigenous women across Canada. However, in the province of Ontario, the ban did not take effect until 2021, and some provinces in Canada still practice alerts.

‘Birth alerts’ built on historic and ongoing colonial practices of Indigenous parents having their children taken away from them by the state. From the 1830s to 1996, the Canadian government created a Residential School System with the goal of taking Indigenous children from their culture and assimilating them into Western Canadian culture, with less than 50% chance of survival.

Moreover, instances such as the ‘Sixties Scoop’, a continuation of the Residential School System, in the 1950s to 1980s saw authorities forcibly removing around 20,000 Indigenous children from their communities, often without telling their families. The ‘Millennial Scoop’, which started in the 1990s, continued a similar practice and has been indicated in research as a pipeline to incarceration and human trafficking. “There are more Indigenous children in care in the present day than there were in the Residential School era,” says Tamara. “Indigenous children continue to not be raised by their families.”

Ongoing impacts

The impacts of these injustices and the trauma forced on Indigenous women are complex and far-reaching. Separating mothers from their children can create a cycle of insecure attachment, where children grow up seeking love from unhealthy relationships because their needs have not been met earlier in life. “We need to acknowledge the intergenerational impact that a lack of secure attachment has on feeling safe and confident in the future,” says Tamara. “Without this understanding of social psychological development, victims are often blamed, and Indigenous trauma-informed support is still lacking, which leads to a failure to address the root causes of these issues – intergenerational trauma and lack of secure attachment impacting social determinants of health.”

Indigenous women are also more likely to have been exposed to family violence, witnessed or been involved in intimate partner violence, or known a family member or friend who became one among missing or murdered. “Indigenous women are often in survival mode at early stages of their life, and are susceptible to being groomed and ‘love bombed’,” explains Tamara. This creates a dangerous cycle where Indigenous women can be manipulated into unhealthy and violent situations.

Pathway from school to Indigenous learning

During high school, study geography, history and communications-based courses such as English, French and other languages. It is also useful to take some maths or statistics classes for understanding data analysis methods.

At university, study for a degree in Indigenous learning or a subject that develops your critical thinking skills and engages with different cultures and perspectives, such as sociology. If you can choose any of your courses, Tamara recommends taking classes in Indigenous history, Indigenous law, Indigenous governance, Indigenous self-determination and advocacy, Indigenous gender-based violence, Indigenous peoples and the land, and Indigenous research.

Visit the Lakehead University admissions page for their Indigenous learning degree, which gives some great information on what the course will involve and potential future careers:

lakeheadu.ca/indigenous/indigenous-programs/indigenous-learning

Have a look at the National Centre for Collaboration in Indigenous Education (nccie.ca/about-us), which has a brilliant resource library with articles about Indigenous learning.

Meet Tamara

The Creator choose this path for me. I was the first generation in my family to not attend residential school. I have the legacy of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in my family. It’s not easy work being a cycle breaker or the first for many things in my life, but I do it with hope to inspire change. I want our world to be a better place for the future generations. This is about breaking a trail for those coming behind me.

One of my roles also involves conducting death reviews under the Chief Coroner, as part of the Domestic Violence Death Review Committee, and I am leading one of the first Indigenous reports of its kind by integrating Indigenous risk factors to address the gaps and barriers within our existing system. I am doing this important work with two other Indigenous women. We are a small team of three in Ontario, but we are mighty, dedicated survivors, and want justice and healing for our women and girls. The time is now for change. Addressing Indigenous gender-based violence is not only political, it is also personal.

My PhD dissertation focuses on understanding the various forms of violence that target Indigenous women, particularly the experiences of violence that women Indigenous students face while pursuing post-secondary education. Although post-secondary institutions can serve as a means of ‘escape’, Indigenous women often fall through the cracks due to a lack of intervention training at the institutional level, including among faculty, staff and administration, on issues such as intimate partner violence and human trafficking.

My work is difficult, so it’s important I look after my own well-being. To do this, I go to ceremonies held on the land and water. They ground me, clear my head and help me to be a better human being, to not carry the trauma I can witness as a helper for Indigenous women and girls. I surround myself with Elders and healers to help me.

It’s difficult to give specific advice about pursuing a career in Indigenous rights-based advocacy, because it’s not one role or title. I have multiple, layered and connected roles, from teaching at the University of Lakehead to my advisory role at Creative Fire, from studying for my PhD to serving on committees, because there are not enough of us to hold government accountable. I’m working to represent Indigenous rights in lots of areas and have often been alone in my efforts.

To become a leader and to be heard, I have had to ensure I have the educational criteria Western society expects. I have been in education for the last 20 years, gaining degrees in sociology, psychology, Indigenous education and research.

To take steps to become more Indigenous trauma informed and to educate yourself on the issues that directly impact Indigenous women, attend Indigenous training that is led by and facilitated by Indigenous Peoples. Go to Indigenous conferences, sit and listen and learn First Nation history. If you’re not Indigenous, ask yourself what it means to be an ally. Ask Indigenous individuals that you have relationships with on what being an ally means to them. So much can be learnt by reading and listening to Indigenous people’s stories.

My proudest achievement is having my son. Due to colonialism, being a mother is a role that many Anishinaabe women in my life did not get the privilege to enjoy. Being a mother is life changing. My aim is to be the mom my son deserves. My son is everything, and being his mother heals so many generations of trauma.

In the future, I also hope to do work for and with United Nations.

Tamara’s top tips

1. Learn as much as you can and have the courage to learn from different perspectives.

2. Remember decolonisation is not an easy journey of learning; it takes great vulnerability. I wish you a wonderful journey of decolonisation. Baamaapii.

Do you have a question for Tamara?

Write it in the comments box below and they will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

Learn about researchers fostering Indigenous-engaged archaeology in Canada:

futurumcareers.com/bringing-indigenous-rights-leadership-and-knowledge-into-archaeology

0 Comments