Does science have all the answers?

Dr Siobhan Maderson, from Aberystwyth University, UK, has been investigating how traditional environmental knowledge is often overlooked by scientists and politicians. Her research into the knowledge of beekeepers could help put sustainable, nature-friendly food on our plates

TALK LIKE A HUMAN GEOGRAPHER

TRADITIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL KNOWLEDGE (TEK) – knowledge about the environment and environmental practices handed down through generations

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES – people native to a place that has been colonised by another ethnic group. Indigenous peoples retain a distinct culture and way of life, which is often threatened by colonial occupiers

COLONIALISM – where a country takes political or economic control over another area and its inhabitants, in order to settle people there or exploit its resources

PARTICIPANT OBSERVATION – a research method whereby the researcher watches someone do an activity, or takes part in it themselves

WHAT IS TRADITIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL KNOWLEDGE?

There are three things that define traditional environmental knowledge (TEK): who teaches it to you, how you learn it, and what you do with it. Firstly, TEK is intergenerational. It is passed to you from older people in your community. Secondly, learning TEK is not about reading a textbook, but a process of learning by doing, like herding reindeer, fishing for salmon or cultivating the land, through which you understand new things about living beings and their relationships with the environment. Finally, TEK is not a fact you memorise for an exam and then forget about, but something you put into practice, develop over your lifetime and pass on to others. TEK often has a strong ethical dimension – you use what you know to help your community, including both humans and other living beings.

WHO HOLDS TEK?

Anybody can hold TEK, but communities who farm, hunt and fish tend to have the richest reserves. Herders know exactly when pastures are ready for grazing, farmers can tell which crops will survive in different types of soil, and fishing communities can locate shoals of fish in a vast tract of ocean.

Indigenous peoples often live directly from the land, giving them a deep connection with their environment. “Their environmental knowledge (also known as indigenous knowledge, or IK) is usually combined with strong ethical values and distinct cultural identity, often including a religious or cosmological sense of connection to the wider physical environment,” says Siobhan.

And TEK can also be found in towns and cities. “If your family have lived in the same locality for three generations, your grandparents might talk about how their laundry gets dirty when they hang it on the line, which didn’t happen when they were younger,” says Siobhan. From their TEK (also known as local environmental knowledge, or LEK), they know that air pollution has increased, and they may wonder if there is a link with increases in asthma in the community.

WHY IS TEK OFTEN NOT RESPECTED?

Scientists have a set idea of how knowledge is produced, and often disregard anything that is not the result of objective experiments. They look for repeatability, clearly defined aims and rigorous statistics. In contrast, it is hard to trace exactly where TEK comes from and it is not repeatable in an experimental setting. Therefore, scientists often consider TEK to be unreliable and subject to bias.

Furthermore, the communities who use TEK in their daily lives tend not to have a lot of political power. Colonialism supresses many of the communities that hold TEK around the globe. They often suffer racism and live in areas exploited by extractive industries, leaving them in poverty and their voices unheard.

Science has become the mainstream way of understanding, discussing and managing the world. This has led to an expectation that politics should be led by scientific knowledge and leaves little room for TEK to influence decisions.

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO COMBINE TEK WITH SCIENTIFIC DATA?

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM202

TRADITIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL KNOWLEDGE (TEK) – knowledge about the environment and environmental practices handed down through generations

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES – people native to a place that has been colonised by another ethnic group. Indigenous peoples retain a distinct culture and way of life, which is often threatened by colonial occupiers

COLONIALISM – where a country takes political or economic control over another area and its inhabitants, in order to settle people there or exploit its resources

PARTICIPANT OBSERVATION – a research method whereby the researcher watches someone do an activity, or takes part in it themselves

WHAT IS TRADITIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL KNOWLEDGE?

There are three things that define traditional environmental knowledge (TEK): who teaches it to you, how you learn it, and what you do with it. Firstly, TEK is intergenerational. It is passed to you from older people in your community. Secondly, learning TEK is not about reading a textbook, but a process of learning by doing, like herding reindeer, fishing for salmon or cultivating the land, through which you understand new things about living beings and their relationships with the environment. Finally, TEK is not a fact you memorise for an exam and then forget about, but something you put into practice, develop over your lifetime and pass on to others. TEK often has a strong ethical dimension – you use what you know to help your community, including both humans and other living beings.

WHO HOLDS TEK?

Anybody can hold TEK, but communities who farm, hunt and fish tend to have the richest reserves. Herders know exactly when pastures are ready for grazing, farmers can tell which crops will survive in different types of soil, and fishing communities can locate shoals of fish in a vast tract of ocean.

Indigenous peoples often live directly from the land, giving them a deep connection with their environment. “Their environmental knowledge (also known as indigenous knowledge, or IK) is usually combined with strong ethical values and distinct cultural identity, often including a religious or cosmological sense of connection to the wider physical environment,” says Siobhan.

And TEK can also be found in towns and cities. “If your family have lived in the same locality for three generations, your grandparents might talk about how their laundry gets dirty when they hang it on the line, which didn’t happen when they were younger,” says Siobhan. From their TEK (also known as local environmental knowledge, or LEK), they know that air pollution has increased, and they may wonder if there is a link with increases in asthma in the community.

WHY IS TEK OFTEN NOT RESPECTED?

Scientists have a set idea of how knowledge is produced, and often disregard anything that is not the result of objective experiments. They look for repeatability, clearly defined aims and rigorous statistics. In contrast, it is hard to trace exactly where TEK comes from and it is not repeatable in an experimental setting. Therefore, scientists often consider TEK to be unreliable and subject to bias.

Furthermore, the communities who use TEK in their daily lives tend not to have a lot of political power. Colonialism supresses many of the communities that hold TEK around the globe. They often suffer racism and live in areas exploited by extractive industries, leaving them in poverty and their voices unheard.

Science has become the mainstream way of understanding, discussing and managing the world. This has led to an expectation that politics should be led by scientific knowledge and leaves little room for TEK to influence decisions.

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO COMBINE TEK WITH SCIENTIFIC DATA?

“Both TEK and scientific data have their benefits for helping us understand our environment,” explains Siobhan. “TEK can bring temporal richness that is often missing from scientific experiments.” Scientific methods struggle with some environmental questions. Long-term experiments are difficult to fund and manage, meaning that scientists rarely have data covering more than a five-year timespan. TEK can fill this gap, as it is built from decades or centuries of people interacting with their environment.

Communities that hold TEK understand their environment in ways which embody sustainable values and emphasise the importance of responsible relationships between all living beings. Policymakers tasked with managing the environment can learn from their knowledge and sustainable practices. It will be crucial to properly value TEK if we are to meet global challenges such as climate change, biodiversity loss, soil degradation and food security.

WHAT TEK DO BEEKEEPERS HOLD?

Many of the beekeepers Siobhan interviewed learnt how to keep bees from their parents or grandparents, meaning the families have an intimate understanding of their local environment. They notice how the timing of the seasons and weather patterns have changed over the decades, affecting both the bees and whole ecosystems. They have seen how changes in land management, such as removal of orchards and the industrialisation of agriculture, have negatively influenced bee health and well-being. Beekeepers constantly update their TEK as they observe these environmental changes and incorporate wider knowledge from biology and botany.

HOW CAN WE LEARN FROM THE TEK OF BEEKEEPERS?

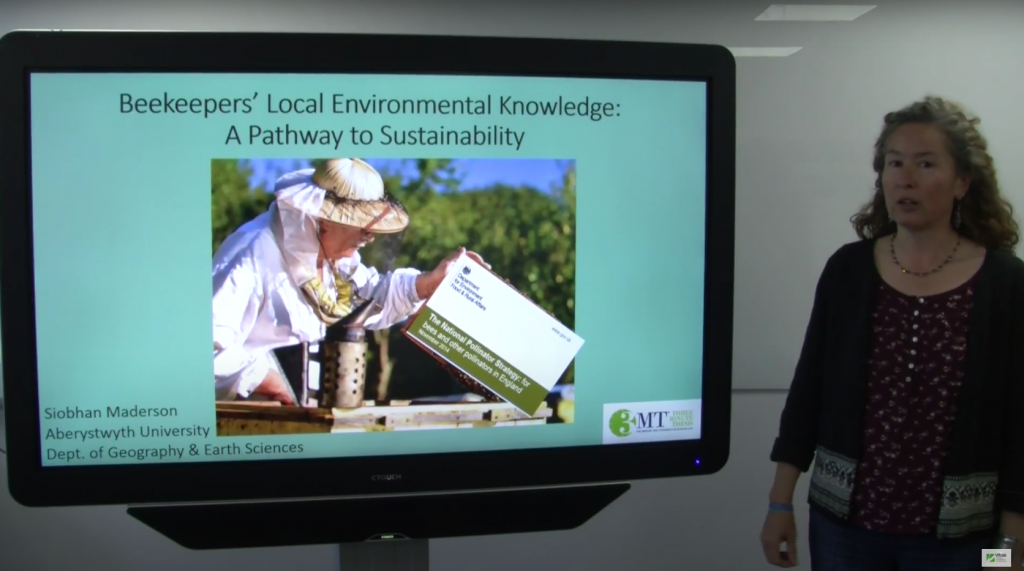

As well as conducting interviews, Siobhan investigates beekeeper TEK by participant observation and archival research. “Archives are amazing! I love them!” she says. By searching through old logbooks and journals kept by beekeepers, she can rediscover knowledge and forgotten stories. Archives reveal detailed descriptions of daily weather, the dates on which different plant species began to flower and records of bee health. Combining this with other environmental data provides insights into how bees are affected by climate change and changes in farming practices.

Archives have also shown how beekeepers have used their TEK in the past, for example to campaign against the use of chemicals that are dangerous to insects. “This gives a rich picture of how beekeepers have worked with scientists and policymakers in the past,” explains Siobhan. “Understanding this is important if we want to use their knowledge effectively, now and in the future.”

CAN TEK HELP US EAT SUSTAINABLY?

Current methods of intensive agriculture leave little room for nature. Large fields of a single crop mean a lack of biodiversity and, as a result, many species of insect are in decline. Siobhan thinks that TEK could hold the key to protecting biodiversity while still producing enough food. Utilising the environmental knowledge held by beekeepers, farmers and other communities around the globe can help us develop more sustainable land use practices. “I’m interested in how people can effectively work together for a better food system that has fewer negative impacts on the environment,” she says. “I hope my research can contribute to better land management, for the sake of all living creatures, and the wider environment we all share.”

DR SIOBHAN MADERSON

DR SIOBHAN MADERSON

Post-Doctoral Researcher, Aberystwyth University, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Human Geography

RESEARCH PROJECT: Investigating how we can use traditional environmental knowledge to help make agriculture more sustainable

FUNDER: Economic and Social Research Council

DR SIOBHAN MADERSON

DR SIOBHAN MADERSON

Post-Doctoral Researcher, Aberystwyth University, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Human Geography

RESEARCH PROJECT: Investigating how we can use traditional environmental knowledge to help make agriculture more sustainable

FUNDER: Economic and Social Research Council

ABOUT HUMAN GEOGRAPHY

Where are humans located around the globe? How do they organise themselves? How do they interact with their environment? These are the broad questions that human geographers tackle, and the answers lie where culture, economics and politics intersect with the physical world.

WHY IS INTERDISCIPLINARITY SO IMPORTANT?

“There is a growing recognition of the importance of interdisciplinary research to solve 21st century challenges,” says Siobhan, who considers herself to be an ‘interdisciplinary researcher’. “Geography is the study of our world,” she says, “of people, rivers, volcanoes, oceans, ecosystems, economics, and so much more. And all of it is interrelated.” This means geography relies on knowledge from many other disciplines to discover and understand these links. While Siobhan’s research primarily lies in the field of human geography, it also relates to many other topics, and she has worked with botanists, soil scientists, ecologists, entomologists, veterinarians, geneticists and international politics researchers. “I love learning about multiple fields,” she says. “Human geography, physical geography, land use, biology – all of these, and more, connect with human geography.”

WHAT ARE THE NEXT BIG CHALLENGES FOR GEOGRAPHERS?

“We are living in a time of many enormous challenges,” says Siobhan, “such as climate change and biodiversity loss. Geography offers many opportunities to tackle these challenges.” Human geographers will have an important role to play in understanding the social, economic and political forces that are driving these problems and in finding solutions to them. It may be a daunting prospect, and stressful at times, but these geographers will be empowered by the knowledge that they are working for the greater good.

EXPLORE A CAREER IN GEOGRAPHY

• The Geographical Association has advice on work experience, volunteer opportunities and career prospects: www.geography.org.uk/Jobs-andcareers-in-geography

• The Royal Geographical Society has lots of information on why you might choose to study geography: www.rgs.org/geography/choose-geography/careers

• Watch this TEDx talk called ‘The Power of Geography to Make a Sustainable Future’ by Lisa Benton-Short: www.youtube.com/watch?v=C6b3pQ8Tox0

• As an interdisciplinary field, most subjects at school will help prepare you for a geography degree at university. A geography degree may cover both human and physical geography, or you may be able to choose which branch to study.

• If you are interested in human geography, subjects such as geography, history, economics, English and philosophy will be useful. If you are interested in physical geography, then geography, maths, biology and physics will provide a good foundation.

• Alternatively, you might transition to human geography from a degree in another field, such as anthropology, politics or sociology. For these degrees, study English and humanities subjects at school.

GEOGRAPHY AT ABERYSTWYTH UNIVERSITY

Aberystwyth University’s Department of Geography and Earth Sciences offers a range of geography degree schemes, all taught by world experts who are happy to help you whenever you need it.

Whether you are interested in studying human geography or physical geography, Aberystwyth provides unique opportunities to study geography in a magnificent setting. You also have the option to explore both branches in more depth, by taking a range of modules in human and physical geography, before deciding which you want to specialise in. “We often find that students’ final decision is different from what they had originally thought they would do when in school,” says Siobhan.

Find out about the different geography degrees and courses offered by the Department of Geography and Earth Sciences at Aberystwyth University at www.aber.ac.uk/en/dges.

HOW DID SIOBHAN BECOME A HUMAN GEOGRAPHER?

I’ve always been a fanatical reader. I’d read anything and everything – novels, sci-fi, history, natural sciences, comic books, humour. And I’ve always loved animals. When I was a kid, I wanted to be a veterinarian, or work with dolphins at an aquarium.

I’ve always been interested in food and the environment – my mum was a chef, and my first job was baking for her. She got me interested in how food was produced, and what environmental issues were affecting our food supplies.

After completing a BSc in Social Anthropology, I spent 24 years working in a range of food and sustainability-related sectors, before returning to university to complete an MSc in Food and Water Security. Working with the Environmental Law Foundation really showed me the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration when trying to fix environmental problems. Then one day, I saw a sign at Aberystwyth University advertising the MSc in Food and Water Security, and I knew it was the course for me. I was particularly drawn to the fact that the course was interdisciplinary, with modules in geography, international politics, biology and environmental sciences.

So many wonderful things have happened since I came back to academia. I’ve made lots of new friends, I’ve spoken at conferences all over Europe, and I was a semi-finalist for the 3 Minute Thesis competition. I was also a finalist for the ESRC ‘Making Sense of Society’ writing competition. I’ve now been awarded an ESRC Post-Doctoral Fellowship, which is a huge honour. This will allow me to build on and publicise my PhD findings. It’s great!

Out of work, I love swimming and paddle boarding. And my dog is the world’s best Frisbee-playing dog – no doubt about it! I also love cooking, baking and watching films with my kids (especially Marvel films – Iron Man is my favourite).

I used to keep bees, and I love the peaceful, quiet engagement with another species and the wider environment. Beekeeping really connects you to the seasons.

SIOBHAN’S TOP TIPS

01 Don’t worry about how your career will unfold, and don’t worry about making mistakes. One step leads to another.

02 Follow your interests, do the right thing by your family and community, and things will fall into place as you go along.

03 Talk to people with lots of different interests. You never know who you’ll end up working with one day!

Do you have a question for Siobhan?

Write it in the comments box below and Siobhan will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)