Educating youth about biosecurity can help prevent the spread of disease in farm animals

Whether a farmer has one sheep or 101 sheep, he or she has to follow biosecurity practices to avoid spreading disease. This means that appropriate policies and incentives – from the farm-level to governmental levels – are needed to reduce the impact of diseases in livestock animals, including dairy and beef cows, horses, pigs, sheep, goats, llamas, alpacas and poultry.

It is also important to ensure everyone receives the message in an actionable way. The aim of the Animal Disease Biosecurity Coordinated Agricultural Project (ADBCAP) is to help develop and instil these much-needed biosecurity protocols and policies in animal agriculture. And the 20-strong team, based at universities all over the United States, has expertise in animal science, veterinary medicine, agricultural economics, public policy, risk communication and education.

WHY SHOULD YOUNG PEOPLE BE EDUCATED ABOUT BIOSECURITY?

By educating the next generation of agricultural producers on biosecurity, protecting animal health becomes a routine life skill. Having an informed and engaged agricultural community can help mitigate risk from endemic (commonly found) and emerging disease-causing agents, which, in turn, creates safer and more profitable agricultural practices. For example, some diseases can only be prevented through biosecurity because there are no known treatments or vaccines. African swine fever and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) are two examples of such diseases.

“We were encouraged by the success of past public health campaigns (such as those against smoking, or promoting the wearing of seatbelts and bike helmets) that were aimed at children and, through them, spread to adults,” says Jeannette McDonald, the ADBCAP’s education lead and Director of TLC Projects, LLC. “We are hoping to see ‘trickle up’ education, from the 6th-12th graders to parents and other adults within their sphere of influence, as well as through active biosecurity advocacy within their communities.”

HOW ARE ADBCAP MATERIALS REACHING YOUNG PEOPLE?

Many of ADBCAP’s outreach team actively engage with 4-H (a national youth development programme located in the United States), the National FFA Organization (a US organisation providing leadership opportunities and experiential learning for students in high school agriculture programmes), and through agricultural extension programmes, which provide non formal learning and research-based educational activities to agricultural communities around the country. However, as Jeannette explains, they also visit schools, agricultural events and other venues that provide opportunities to discuss biosecurity.

Currently, the team offers modules in animal biosecurity risks and strategies, infection and disease transmission, and is developing further modules to train young people to become biosecurity advocates in their communities. For example, helping to spread the word about these biosecurity risks and strategies would make you a biosecurity advocate.

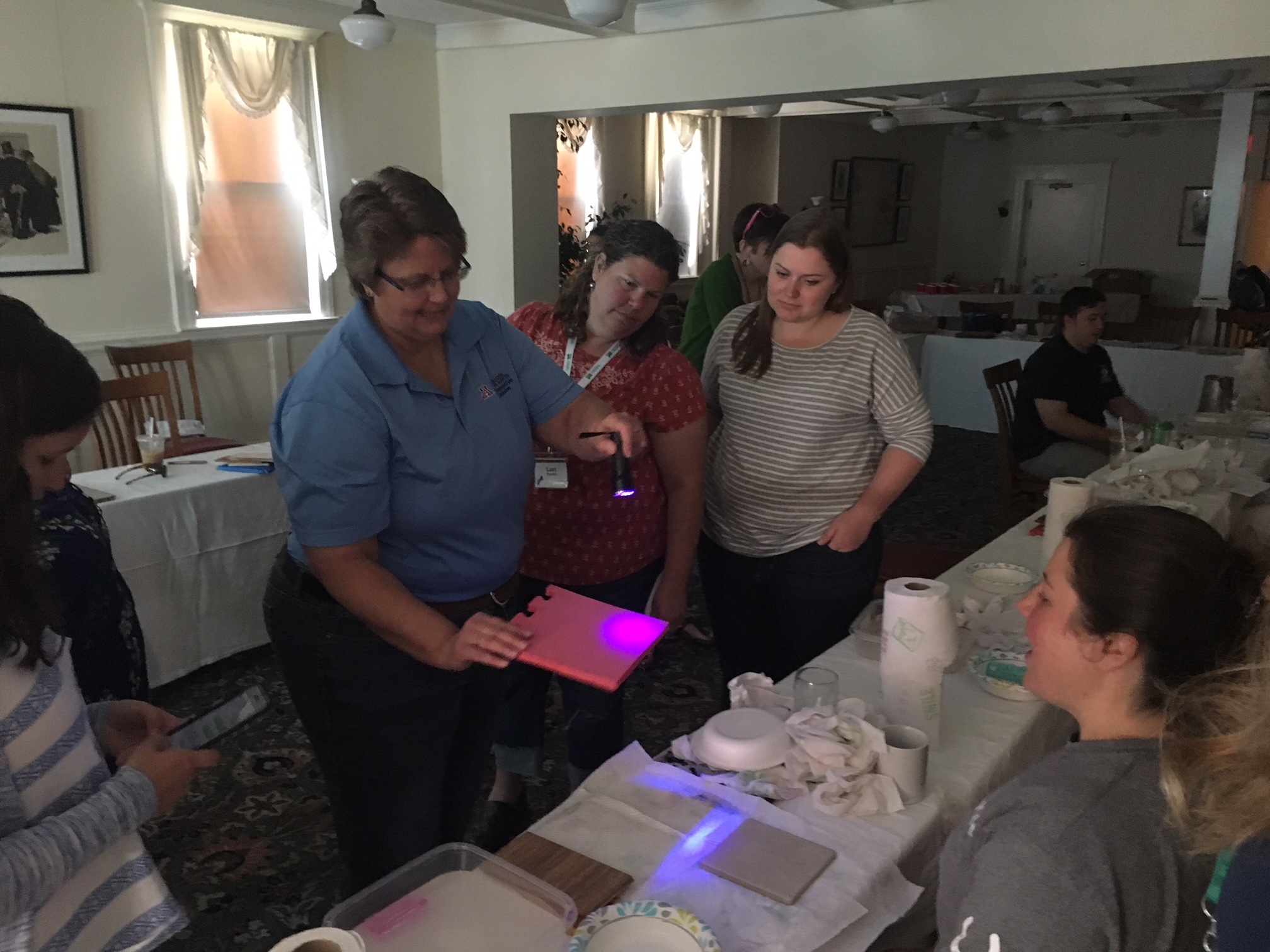

An accompanying Teacher’s Guide (still under development) will include activities and materials to support and extend these modules. In addition, the outreach team has developed a complementary programme of hands-on activities to reinforce the lessons in the modules, called SCRUB (Science Creates Real Understanding of Biosecurity).

WHAT HAS BEEN THE OUTCOME OF THESE OUTREACH ACTIVITIES?

ADBCAP has been going for four years, and the team’s education and outreach activities are in the final stages of development. In this short timescale, some positive outcomes have already been identified: “We have pilot data that suggests changes in awareness of the importance of biosecurity in general,” says Jeannette, “and an increase in understanding and acknowledgement of the importance of hand washing and changing footwear, specifically.” Agricultural teachers participating in preliminary SCRUB laboratory testing/evaluation activities in Massachusetts and Oklahoma have also responded positively.

This is certainly a step in the right direction. By instilling a good understanding of and enthusiasm for biosecurity in both educators and youth, the ADBCAP team is laying the foundation for improving animal welfare, reducing the spread of animal diseases and protecting farmers’ livelihoods for the next generation.

Biosecurity is a wide field, encompassing many different disciplines. Broadly, it can be described as a set of procedures designed to protect the health of humans, animals and plants. These biosecurity procedures range from containment strategies for disease outbreaks, to safe and secure housing and sharing knowledge and skills, which lead to proactive human behaviours in disease prevention through responsible animal management.

WHY DO WE NEED TO TAKE BIOSECURITY SERIOUSLY?

Any industry involving animals depends on biosecurity. An animal breeder who takes in a sick animal without quarantine could infect the whole herd. Professional horse trainers whose students allow their show horses to drink out of a common water trough at a show put their animals at risk. A veterinarian travelling between barns, not using proper biosecurity protocols, could transmit disease.

An animal’s risk of disease or health problems can be reduced dramatically by providing suitable vaccinations and appropriate, timely veterinary care, as well as controlling interactions with other, potentially infectious animals. An animal’s quality of life can also be improved by making sure they have comfortable, safe housing; that their environmental needs are met; and that they experience no unnecessary stress.

Good biosecurity protocols also benefit humans, from both a health and economic perspective. They benefit farmers by reducing risks to animals’ health, which directly affects food production and farm profitability. By controlling animal diseases, biosecurity also keeps domestic and international trade channels open, enables low food prices, and promotes consumer confidence in food safety and wholesomeness. Lastly, some diseases carried by farm animals are zoonotic, meaning they can be transmitted between animals and humans, sometimes with more serious effects. Avian flu is one example of a zoonotic disease. Strong biosecurity protocols therefore protect animals, the economy, the environment and humans.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM34

Whether a farmer has one sheep or 101 sheep, he or she has to follow biosecurity practices to avoid spreading disease. This means that appropriate policies and incentives – from the farm-level to governmental levels – are needed to reduce the impact of diseases in livestock animals, including dairy and beef cows, horses, pigs, sheep, goats, llamas, alpacas and poultry.

It is also important to ensure everyone receives the message in an actionable way. The aim of the Animal Disease Biosecurity Coordinated Agricultural Project (ADBCAP) is to help develop and instil these much-needed biosecurity protocols and policies in animal agriculture. And the 20-strong team, based at universities all over the United States, has expertise in animal science, veterinary medicine, agricultural economics, public policy, risk communication and education.

WHY SHOULD YOUNG PEOPLE BE EDUCATED ABOUT BIOSECURITY?

By educating the next generation of agricultural producers on biosecurity, protecting animal health becomes a routine life skill. Having an informed and engaged agricultural community can help mitigate risk from endemic (commonly found) and emerging disease-causing agents, which, in turn, creates safer and more profitable agricultural practices. For example, some diseases can only be prevented through biosecurity because there are no known treatments or vaccines. African swine fever and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) are two examples of such diseases.

“We were encouraged by the success of past public health campaigns (such as those against smoking, or promoting the wearing of seatbelts and bike helmets) that were aimed at children and, through them, spread to adults,” says Jeannette McDonald, the ADBCAP’s education lead and Director of TLC Projects, LLC. “We are hoping to see ‘trickle up’ education, from the 6th-12th graders to parents and other adults within their sphere of influence, as well as through active biosecurity advocacy within their communities.”

HOW ARE ADBCAP MATERIALS REACHING YOUNG PEOPLE?

Many of ADBCAP’s outreach team actively engage with 4-H (a national youth development programme located in the United States), the National FFA Organization (a US organisation providing leadership opportunities and experiential learning for students in high school agriculture programmes), and through agricultural extension programmes, which provide non formal learning and research-based educational activities to agricultural communities around the country. However, as Jeannette explains, they also visit schools, agricultural events and other venues that provide opportunities to discuss biosecurity.

Currently, the team offers modules in animal biosecurity risks and strategies, infection and disease transmission, and is developing further modules to train young people to become biosecurity advocates in their communities. For example, helping to spread the word about these biosecurity risks and strategies would make you a biosecurity advocate.

An accompanying Teacher’s Guide (still under development) will include activities and materials to support and extend these modules. In addition, the outreach team has developed a complementary programme of hands-on activities to reinforce the lessons in the modules, called SCRUB (Science Creates Real Understanding of Biosecurity).

WHAT HAS BEEN THE OUTCOME OF THESE OUTREACH ACTIVITIES?

ADBCAP has been going for four years, and the team’s education and outreach activities are in the final stages of development. In this short timescale, some positive outcomes have already been identified: “We have pilot data that suggests changes in awareness of the importance of biosecurity in general,” says Jeannette, “and an increase in understanding and acknowledgement of the importance of hand washing and changing footwear, specifically.” Agricultural teachers participating in preliminary SCRUB laboratory testing/evaluation activities in Massachusetts and Oklahoma have also responded positively.

This is certainly a step in the right direction. By instilling a good understanding of and enthusiasm for biosecurity in both educators and youth, the ADBCAP team is laying the foundation for improving animal welfare, reducing the spread of animal diseases and protecting farmers’ livelihoods for the next generation.

Biosecurity is a wide field, encompassing many different disciplines. Broadly, it can be described as a set of procedures designed to protect the health of humans, animals and plants. These biosecurity procedures range from containment strategies for disease outbreaks, to safe and secure housing and sharing knowledge and skills, which lead to proactive human behaviours in disease prevention through responsible animal management.

WHY DO WE NEED TO TAKE BIOSECURITY SERIOUSLY?

Any industry involving animals depends on biosecurity. An animal breeder who takes in a sick animal without quarantine could infect the whole herd. Professional horse trainers whose students allow their show horses to drink out of a common water trough at a show put their animals at risk. A veterinarian travelling between barns, not using proper biosecurity protocols, could transmit disease.

An animal’s risk of disease or health problems can be reduced dramatically by providing suitable vaccinations and appropriate, timely veterinary care, as well as controlling interactions with other, potentially infectious animals. An animal’s quality of life can also be improved by making sure they have comfortable, safe housing; that their environmental needs are met; and that they experience no unnecessary stress.

Good biosecurity protocols also benefit humans, from both a health and economic perspective. They benefit farmers by reducing risks to animals’ health, which directly affects food production and farm profitability. By controlling animal diseases, biosecurity also keeps domestic and international trade channels open, enables low food prices, and promotes consumer confidence in food safety and wholesomeness. Lastly, some diseases carried by farm animals are zoonotic, meaning they can be transmitted between animals and humans, sometimes with more serious effects. Avian flu is one example of a zoonotic disease. Strong biosecurity protocols therefore protect animals, the economy, the environment and humans.

Because biosecurity is such a broad field, it offers many career options. Some people working in biosecurity have backgrounds in veterinary medicine and/or animal science, which equips them to consider the animals’ medical needs as well as develop plans with farmers and local governments for protecting animal health. Others have a broader biological background, approaching biosecurity from the perspective of animal behaviour, genetics or patterns of disease transmission. Educators and communicators play a vital role in biosecurity, too, offering training and education in best practises. The huge array of products involved in animal care mean that those with an interest in manufacturing or marketing also have a role to play. It is a field in which a range of interests and strengths can be used to make positive changes for humans and animals.

JEANNETTE MCDONALD, DVM, PHD

JEANNETTE MCDONALD, DVM, PHDProfessor Emerita, University of Wisconsin-Madison, and CEO and Executive Director of TLC Projects, LLC

I’m the lead for the education team, which creates online education products. This means I organise the work of the team, guide them in designing the modules and liaise with developers.

My bachelor’s degree was in education, which I followed with a doctorate in veterinary medicine. After a time spent in veterinary research, I pursued a PhD in adult education, focusing on continuing professional education. I took the first online course offered at my university, and it hooked me on distance education: I’ve been a strong advocate ever since. Now I use my expertise in teaching online to teach about veterinary medical topics such as biosecurity. I love that my courses are available to anyone, anytime, anywhere.

We have a better chance changing attitudes and habits with our youth – our next generation of livestock producers – than with adults. Biosecurity is essential to the health of agricultural communities. These youths can change attitudes and habits now and in the future.

BETSY GREENE, PHD

BETSY GREENE, PHDProfessor and Equine Extension Specialist, School of Animal and Comparative Biomedical Sciences, University of Arizona

I am creating the hands-on classroom activities (SCRUB kits) with Dr Kris Hiney (Oklahoma State University). These kits demonstrate and expand upon key concepts taught in our modules, and are designed to be used by instructors, educators and volunteers.

I began working at a stable in Massachusetts at the age of 11 for $20 a week and a riding lesson, learning all aspects of horse care. I also worked in a feed store warehouse. These experiences sparked my interest in an animal-related career. I completed a veterinary technology programme (support staff in a veterinary practise), and continued to completion of my doctoral degree, with research focused in equine muscle biology/exercise physiology. My career in teaching and extension education spans over 26 years and three universities.

If you are interested in working with animals there is a vast choice of options in career areas and education, depending whether your interests lie in the physical, intellectual or even psychological aspects of the industry. Careers can range from hands-on training, breeding and manufacturing products, to careers requiring advanced degrees such as research and veterinary sciences.

SUSAN KERR, DVM, PHD

SUSAN KERR, DVM, PHD Professor Emerita and (retired) Livestock and Dairy Extension Specialist, Washington State University Extension

I help develop educational online modules for those interested in learning about biosecurity in an enjoyable, engaging and memorable way.

I worked in mixed animal rural veterinary practice for seven years. It became increasingly frustrating to have the knowledge and skills to be able to help animals but hamstrung by owners’ financial situations. I decided to focus more on the educational, preventative aspects of working with animals, so I entered graduate school to learn to teach effectively.

I can’t think of a better way to address animal welfare than by preventing the pain, suffering, and death associated with diseases. By enacting biosecurity measures, owners ensure animals have clean food, water and housing, protection from predators and parasites, appropriate veterinary care and low-stress lives.

Good communication and teamwork skills are very important in these industries, along with a lifelong interest in learning. My advice to young people is to pay attention to aspects of your work that bring you the most joy and capture your attention most: Is it animal behaviour? Genetics? Direct animal care? We need people doing all these things, so there is a career for you with animals!

JEANNE RANKIN, DVM

JEANNE RANKIN, DVMAssociate Specialist in Animal Health, Animal Disaster and Agrosecurity, Montana State University Extension

I’m a subject matter expert in biosecurity for the education team and a USDA Foreign Animal Disease Diagnostician (FADD).

I was raised on a cattle ranch and grain farm in Montana. I was an ambulatory veterinarian for 17 years before becoming Montana’s assistant state veterinarian and acting state veterinarian. After six years,

I became Montana State University Extension’s programme lead for animal disaster, animal health and agrosecurity planning. I help local organisations create an agriculture disaster plan unique to their region. It seemed a great fit when I was asked to join the biosecurity education team, and it has been deeply rewarding.

Good biosecurity protocols decrease animals’ pain and suffering, as well as death rates and treatment costs. Biosecurity strategies reduce risk to humans and animals, as many diseases can transfer between us. The basic animal biosecurity plan is easy and inexpensive to implement while dramatically reducing disease transmission.

There is not a more fulfilling life than caring for animals. Being outdoors working with nature and raising food for the world gives you self-satisfaction and self-worth.