Exploring the life and works of Roberto Gerhard, the electronic music pioneer

While we might think of electronic music as a new style that has emerged in recent decades, its roots can be traced back much further, to when electronic equipment first became available. At the University of Huddersfield in the UK, Professor Monty Adkins and Dr Sam Gillies are examining the work of one of the key pioneers in the field – Roberto Gerhard. By digitising his recordings, they are creating an accessible archive to bring Gerhard’s music, and the character of the man himself, to a contemporary audience.

TALK LIKE AN ELECTRONIC MUSICIAN

DIGITISATION – the process of converting analogue media into a digital format

ELECTRONIC MUSIC – any music involving electronic processing, such as recording or editing

MIXER – sometimes called a mixing desk, a device that can take various audio sources and combine them to produce different outputs

MODERNISM – in music, a broad time period encompassing much of the 20th century, involving innovative approaches to reinterpreting ‘traditional’ musical techniques

SYNTHESIS – the process of creating sounds using electronic signals

TEXTURE – in music, how different aspects are combined in composition to determine an overall quality of sound

TIMBRE – the ‘tone colour’, or perceived sound quality, of a musical note

Electronic music is prevalent everywhere in today’s world, from films to clubs to personal playlists. Despite this ubiquity, like anything, electronic music has its roots – and Roberto Gerhard was one of the first composers of this new musical style in the mid-20th century. At the University of Huddersfield, Professor Monty Adkins, Professor of Experimental Electronic Music, and postdoctoral researcher Dr Sam Gillies, are working to bring Gerhard’s music and inspirations to public prominence.

THE MAN BEHIND THE MUSIC

As with all artists, Gerhard’s work was heavily influenced by the circumstances of his personal life. Born in 1896 in Catalonia, a region of northern Spain with a strong independent identity, he spent his student days studying in Vienna and Berlin with the composer Arnold Schoenberg. “When Gerhard returned to Catalonia, he was seen as a leading modernist – someone who was doing something really new in music,” says Monty. “However, he remained passionate about his homeland and his work referenced a lot of Spanish and Catalan folk melodies.”

In 1936, the Spanish Civil War began in earnest. With nationalist forces threatening the mostly republican Catalonia, Gerhard and his wife made the difficult decision to leave their home country. They travelled first to Paris and then to Cambridge, and from the 1940s Gerhard was working as a freelance composer in England. “Gerhard’s exile meant that he had to take on a lot of jobs writing music for theatre, radio, and later, film, as well as composing for the concert hall,” says Monty. “It was because he was writing a lot of incidental music that he became interested in electronic sound.”

GERHARD’S MUSICAL CAREER

In the 1940s and 1950s, the range of electronic recording equipment available was very limited. “Gerhard originally used a Panatrope, an early record player, to play recorded instrumental cues for theatre productions,” says Sam. “He then began using his own tape machines to record all kinds of sounds and transform them.” Gerhard’s novel use of electronic sound for a 1955 production of Shakespeare’s King Lear created public excitement in England and beyond, kick-starting his work with major organisations including the BBC and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

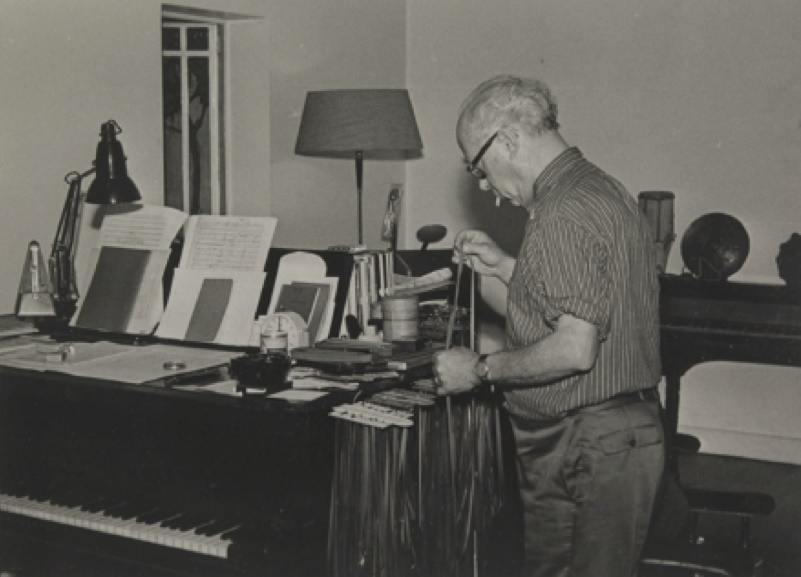

Gerhard was one of the very first people in England to create a home electronic music studio. “When fully developed, Gerhard’s home studio consisted of one microphone, five reel-to-reel tape machines, and a five-track mixer,” says Sam. This sounds very minimal compared to today’s standards, but the limitations of the technology at the time led Gerhard to be more inventive and imaginative with the tools at his disposal.

WHAT MAKES GERHARD’S WORK SPECIAL?

“Gerhard is a fascinating character,” says Monty. “What he chose to record, how he used the technology he had available to change the sound, and how he then used it in the final version of a piece is always a wonderful process to investigate.” As researchers, Monty and Sam not only listen to Gerhard’s work, but also read letters written by or to Gerhard and those around him, looking for clues as to how and why Gerhard made the music he did.

Monty has been exploring how Gerhard would split his work into small sections and release them as ‘library’ pieces for purchase. Though this is a common practice today, Gerhard was one of the first serious composers to do this. Meanwhile, Sam has been investigating Gerhard’s involvement in the music for The Prisoner in 1954, the first piece of theatre music in England to use electronics. As they explain, “He really was a pioneer!”

Despite creating music for film and theatre, Gerhard was also a composer of so-called ‘serious’ concert music. “Gerhard successfully fused a number of concepts drawn from the developing ideologies of electronic music at the time with his own ideas of what electronic music could and should be,” says Monty. “This commitment to his personal vision resulted in the production of music unlike anything else in existence at the time.” These sophisticated ideas were very apparent in his work for film and television, helping to bring his novel compositions to a mainstream audience.

BRINGING A MODERNIST INTO OUR MODERN WORLD

Monty and Sam have painstakingly reconstructed a comprehensive open-access archive of Gerhard’s work, to bring it to a new generation of listeners and composers. “His work was originally digitised in 2012, but technology moves fast, and those files and the associated database are now not compatible with our current technology,” says Sam. This highlighted the importance of ensuring that, this time round, digitised files are created in a format that provides backwards compatibility.

As well as digitising all 610 tapes in the Roberto Gerhard Archive, Monty and Sam also processed the recordings of each tape to remove silence, clicks and unwanted noise found in the tapes, leaving just the electronic music. “We also spent considerable time transcribing interviews, radio broadcasts, recording sessions and so on,” says Monty, who believes that gaining insight into Gerhard’s character and background is essential to understanding his music. “We hope that composers will use the archive to not only listen to Gerhard’s electronic music, but also to better understand his working process.” This means that we can experience how Gerhard used different inspirations, raw materials and manipulations of sound to end up with the finished product.

With all recordings digitised, Monty and Sam have constructed an accessible, online archive of Gerhard’s work, so that everyone can enjoy his music. Why don’t you explore the archives yourself? Visit www.heritagequay.org/rgda/roberto-gerhard to discover Gerhard’s creations and experience the music of this pioneering artist.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM269

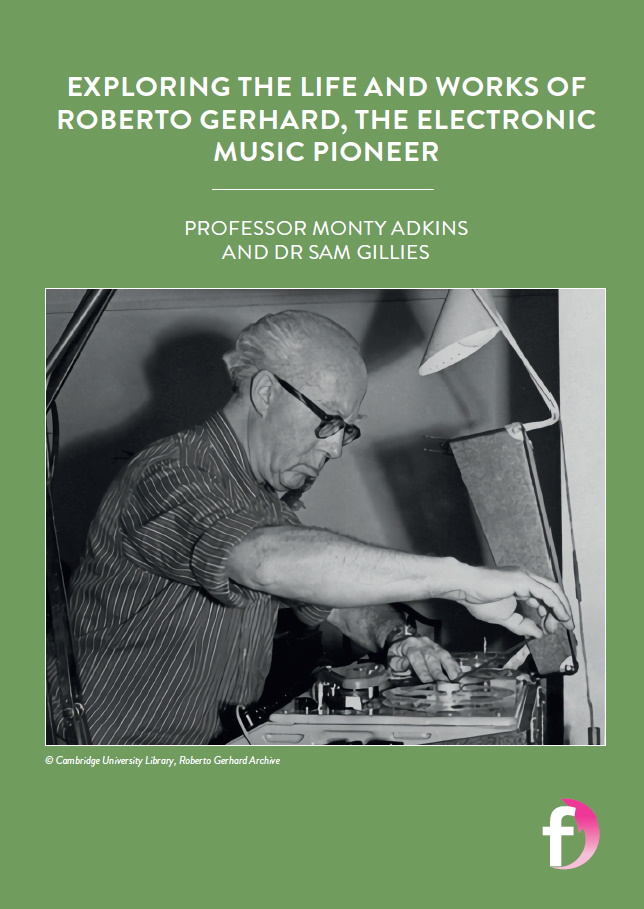

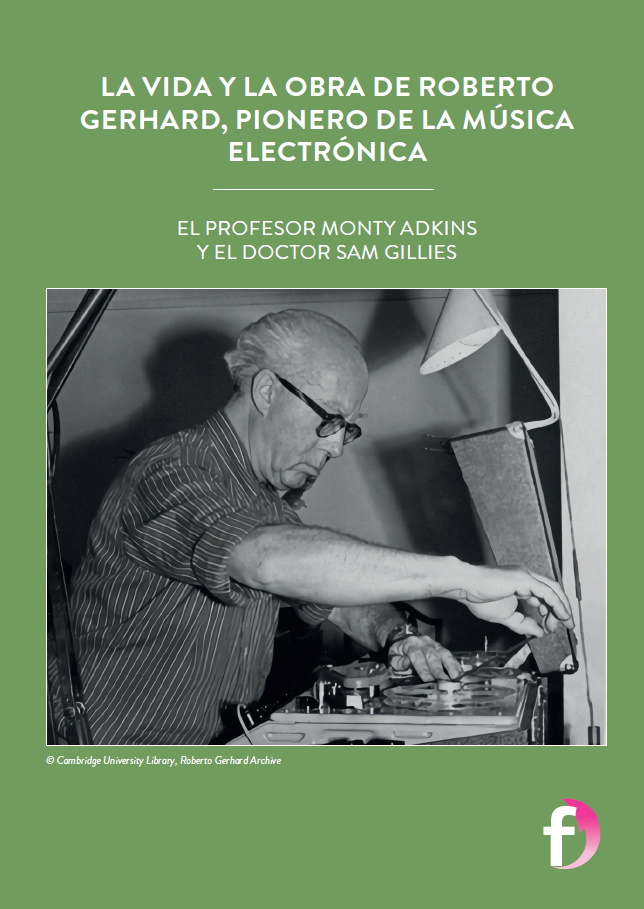

Gerhard in his studio. © Cambridge University Library, Roberto Gerhard Archive

Gerhard in his studio. © Cambridge University Library, Roberto Gerhard Archive

DIGITISATION – the process of converting analogue media into a digital format

ELECTRONIC MUSIC – any music involving electronic processing, such as recording or editing

MIXER – sometimes called a mixing desk, a device that can take various audio sources and combine them to produce different outputs

MODERNISM – in music, a broad time period encompassing much of the 20th century, involving innovative approaches to reinterpreting ‘traditional’ musical techniques

SYNTHESIS – the process of creating sounds using electronic signals

TEXTURE – in music, how different aspects are combined in composition to determine an overall quality of sound

TIMBRE – the ‘tone colour’, or perceived sound quality, of a musical note

Electronic music is prevalent everywhere in today’s world, from films to clubs to personal playlists. Despite this ubiquity, like anything, electronic music has its roots – and Roberto Gerhard was one of the first composers of this new musical style in the mid-20th century. At the University of Huddersfield, Professor Monty Adkins, Professor of Experimental Electronic Music, and postdoctoral researcher Dr Sam Gillies, are working to bring Gerhard’s music and inspirations to public prominence.

THE MAN BEHIND THE MUSIC

As with all artists, Gerhard’s work was heavily influenced by the circumstances of his personal life. Born in 1896 in Catalonia, a region of northern Spain with a strong independent identity, he spent his student days studying in Vienna and Berlin with the composer Arnold Schoenberg. “When Gerhard returned to Catalonia, he was seen as a leading modernist – someone who was doing something really new in music,” says Monty. “However, he remained passionate about his homeland and his work referenced a lot of Spanish and Catalan folk melodies.”

In 1936, the Spanish Civil War began in earnest. With nationalist forces threatening the mostly republican Catalonia, Gerhard and his wife made the difficult decision to leave their home country. They travelled first to Paris and then to Cambridge, and from the 1940s Gerhard was working as a freelance composer in England. “Gerhard’s exile meant that he had to take on a lot of jobs writing music for theatre, radio, and later, film, as well as composing for the concert hall,” says Monty. “It was because he was writing a lot of incidental music that he became interested in electronic sound.”

GERHARD’S MUSICAL CAREER

In the 1940s and 1950s, the range of electronic recording equipment available was very limited. “Gerhard originally used a Panatrope, an early record player, to play recorded instrumental cues for theatre productions,” says Sam. “He then began using his own tape machines to record all kinds of sounds and transform them.” Gerhard’s novel use of electronic sound for a 1955 production of Shakespeare’s King Lear created public excitement in England and beyond, kick-starting his work with major organisations including the BBC and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

Gerhard was one of the very first people in England to create a home electronic music studio. “When fully developed, Gerhard’s home studio consisted of one microphone, five reel-to-reel tape machines, and a five-track mixer,” says Sam. This sounds very minimal compared to today’s standards, but the limitations of the technology at the time led Gerhard to be more inventive and imaginative with the tools at his disposal.

WHAT MAKES GERHARD’S WORK SPECIAL?

“Gerhard is a fascinating character,” says Monty. “What he chose to record, how he used the technology he had available to change the sound, and how he then used it in the final version of a piece is always a wonderful process to investigate.” As researchers, Monty and Sam not only listen to Gerhard’s work, but also read letters written by or to Gerhard and those around him, looking for clues as to how and why Gerhard made the music he did.

Monty has been exploring how Gerhard would split his work into small sections and release them as ‘library’ pieces for purchase. Though this is a common practice today, Gerhard was one of the first serious composers to do this. Meanwhile, Sam has been investigating Gerhard’s involvement in the music for The Prisoner in 1954, the first piece of theatre music in England to use electronics. As they explain, “He really was a pioneer!”

Despite creating music for film and theatre, Gerhard was also a composer of so-called ‘serious’ concert music. “Gerhard successfully fused a number of concepts drawn from the developing ideologies of electronic music at the time with his own ideas of what electronic music could and should be,” says Monty. “This commitment to his personal vision resulted in the production of music unlike anything else in existence at the time.” These sophisticated ideas were very apparent in his work for film and television, helping to bring his novel compositions to a mainstream audience.

BRINGING A MODERNIST INTO OUR MODERN WORLD

Monty and Sam have painstakingly reconstructed a comprehensive open-access archive of Gerhard’s work, to bring it to a new generation of listeners and composers. “His work was originally digitised in 2012, but technology moves fast, and those files and the associated database are now not compatible with our current technology,” says Sam. This highlighted the importance of ensuring that, this time round, digitised files are created in a format that provides backwards compatibility.

As well as digitising all 610 tapes in the Roberto Gerhard Archive, Monty and Sam also processed the recordings of each tape to remove silence, clicks and unwanted noise found in the tapes, leaving just the electronic music. “We also spent considerable time transcribing interviews, radio broadcasts, recording sessions and so on,” says Monty, who believes that gaining insight into Gerhard’s character and background is essential to understanding his music. “We hope that composers will use the archive to not only listen to Gerhard’s electronic music, but also to better understand his working process.” This means that we can experience how Gerhard used different inspirations, raw materials and manipulations of sound to end up with the finished product.

With all recordings digitised, Monty and Sam have constructed an accessible, online archive of Gerhard’s work, so that everyone can enjoy his music. Why don’t you explore the archives yourself? Visit www.heritagequay.org/rgda/roberto-gerhard to discover Gerhard’s creations and experience the music of this pioneering artist.

PROFESSOR MONTY ADKINS

PROFESSOR MONTY ADKINS

Professor of Experimental Electronic Music, University of Huddersfield, UK

DR SAM GILLIES

Postdoctoral Researcher, University of Huddersfield, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Music Technology

RESEARCH PROJECT: Gerhard Revealed: Digitising the work of Roberto Gerhard, making it accessible to a contemporary audience

FUNDER: Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC)

PROFESSOR MONTY ADKINS

PROFESSOR MONTY ADKINS

Professor of Experimental Electronic Music, University of Huddersfield, UK

DR SAM GILLIES

Postdoctoral Researcher, University of Huddersfield, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Music Technology

RESEARCH PROJECT: Gerhard Revealed: Digitising the work of Roberto Gerhard, making it accessible to a contemporary audience

FUNDER: Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC)

ABOUT ELECTRONIC MUSIC

WHAT DEFINES ELECTRONIC MUSIC?

“Most fundamentally, electronic music utilises the flow of electrons, as opposed to natural resonances, to generate sound waves,” says Monty. “This means that electronic music allows for the creation of sounds that are not possible with traditional instrumental music.” This means that electronic music is difficult to classify as a ‘genre’, since it can incorporate such a vast range of different sounds and styles. Any possible sound that can be recorded or synthesised is fair game for inclusion in electronic music. “Electronic music can be made out of any sound. It can be about timbre, texture and strange harmonies that are impossible on instruments, or creating weird atmospheres or very deep physical sounds.”

HOW DO ELECTRONIC MUSIC COMPOSERS CREATE THEIR WORK?

“Electronic music is made and recorded directly onto a tape or, these days, a computer by the composer,” says Sam. “There are no intermediaries.” This differs from ‘traditional’ music, where composers write notes on paper or a screen – essentially creating a set of ‘instructions’ for the players. Electronic music bypasses this step completely, meaning the composer has full control over the finished product. “The composer of electronic music shapes every last sound, every last part, just like a sculptor or painter creates their work of art,” says Sam.

HOW HAS ELECTRONIC MUSIC COMPOSITION CHANGED OVER TIME?

“You can trace electronic music as far back as the Industrial Revolution, when electricity first began to be harnessed,” says Monty. “For instance, Thaddeus Cahill’s Telharmonium, patented in 1897, was an electrical organ that transmitted sound via telephone wires.” Since then, as electronic technology advanced, electronic music followed suit. “The use of tape machines for making experimental music really developed from the late 1940s and early 1950s,” says Sam. “This indicates how pioneering Gerhard was, having his own private recording studio by 1954.” The development of computers heralded a new era for creating electronic music, with endless possibilities now available for electronic composition.

HOW CAN YOU GET INVOLVED IN ELECTRONIC MUSIC?

“It has never been easier to work with electronic music!” says Monty. “You can download composition programmes such as Audacity or Reaper on almost any computer and your phone can capture raw audio recordings of interesting sounds you find in the world.” There is a whole host of software, apps and sample libraries available that mean can you begin composing electronic music almost immediately!

Sam advises simply listening to a lot of music, including music that may not immediately be to your liking. “The stuff you do not like is in some ways more meaningful than the stuff you do,” he says. “Learn to express why you do not like it and think about whether you can find interesting features within it.” This self-critical process can help inform decisions around composition – including aspects that people may enjoy, or some that could challenge existing preconceptions.

EXPLORE A CAREER IN ELECTRONIC MUSIC

• There are a wide range of careers available in electronic music. For example, creative industries such as film, radio, broadcasting and production all use electronic music.

• Careers in Music has blogs and articles about all aspects of working in the music industry: www.careersinmusic.com

• Prospects provides information about careers in music production, including the type of work you might do and the salary you can expect: www.prospects.ac.uk/job-profiles/music-producer

• This blog post explores a pathway for getting into electronic music production in a personable and relatable way: www.edmprod.com/5-stages-electronic-music-producer

• Many universities and colleges offer courses in music production, studio recording and electronic music, all of which lend themselves to a career in the sector.

• Monty recommends learning about the historical and artistic context surrounding the emergence of electronic music. At school, this can translate into taking subjects such as English literature, history, drama, art, and, of course, music.

HOW DID MONTY BECOME A MUSIC RESEARCHER AND COMPOSER?

HOW DOES YOUR PROFESSORIAL ROLE INFORM YOUR CREATIVE OUTPUTS?

First and foremost, I am a creative person. I make music and have worked as a sound designer. Being able to teach this to students is very inspiring. They always have new ideas and suggest I listen to new music. Additionally, the research I do often feeds directly into my creative work. Even the work on Gerhard, which is more ‘historical’, has made me think about how we use the technology we have and about creative ways of working with sound.

WHY DID YOU TRANSITION FROM STUDYING FRENCH MEDIEVAL AND ITALIAN RENAISSANCE MUSIC TO MORE MODERN ELECTRONIC MUSIC?

I have always been fascinated by very early music and very new music. Early music is unusual in terms of harmony, form and old instruments. A lot of these different ways of making music 500-800 years ago can be reinterpreted and applied to electronic music in a creative way.

WHAT IS YOUR FAVOURITE FACT ABOUT GERHARD?

There are wonderful letters about Gerhard and his wife, Poldi, recording the audio of things rolling down the stairs in the middle of the night when it was very quiet. In addition, listening to Gerhard and Poldi record piano and accordion sounds together shows a really human side to them both.

WHAT DO YOU ENJOY DOING IN YOUR FREE TIME?

When I have free time, I like cycling and spending time with my partner – she is also artistic, so I end up making things with her too. Other than that, I am always listening to music and composing. Even when I take a break from work, I am still thinking about music.

HOW DID SAM BECOME A MUSIC RESEARCHER AND COMPOSER?

HOW DOES YOUR ROLE AS A RESEARCHER COMPLEMENT YOUR COMPOSITION AND PERFORMANCE WORK?

They are different but related, with each informing the other. Both are creative in their own way, with research allowing me to focus on exploring narratives and stories that exist around electronic music, and composition exploring more fundamental ideas of what music can be and what it can express. I see them as fundamentally linked.

HOW DID YOUR UNDERGRADUATE DEGREES LEAD TO YOUR CURRENT POSITION?

I first studied an arts degree in communication studies, which was a good place to learn more generally about the variety of artistic concerns throughout the 20th century and to hone my skills in writing and research. When I pursued a degree in music composition a few years later, I could easily translate this experience into my musical practice.

WHAT DO YOU ENJOY DOING IN YOUR FREE TIME?

I’m a fan of professional wrestling and have found that a firm understanding of kayfabe – the portrayal of staged wrestling events as ‘real’ – is helpful in making sense of the music world. I listen to a lot of music outside of work hours, trawling through different albums to try and find weird and interesting ideas. I don’t think you choose a life in music if you lack an insatiable interest in it!

MONTY AND SAM’S TOP TIPS

01 Learn to love to read. Many of the best ideas are not communicable any other way, and if you do not learn to love diving into ideas expressed in written form, then some of the most important concepts of our time will not reach you.

02 Learn to be inquisitive and do not accept the goal-oriented status quo. Do things your way and have the confidence to give anything a go. If it does not work, the experience may still lead to something you would never have done if you had not tried.

03 Take time to experiment and find out what it is about music, technology and being creative that really drives you. That way you will have an original voice and something to contribute that is truly you.

Do you have a question for Monty or Sam?

Write it in the comments box below and Monty or Sam will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)