Exposing environmental injustice through maps and stories

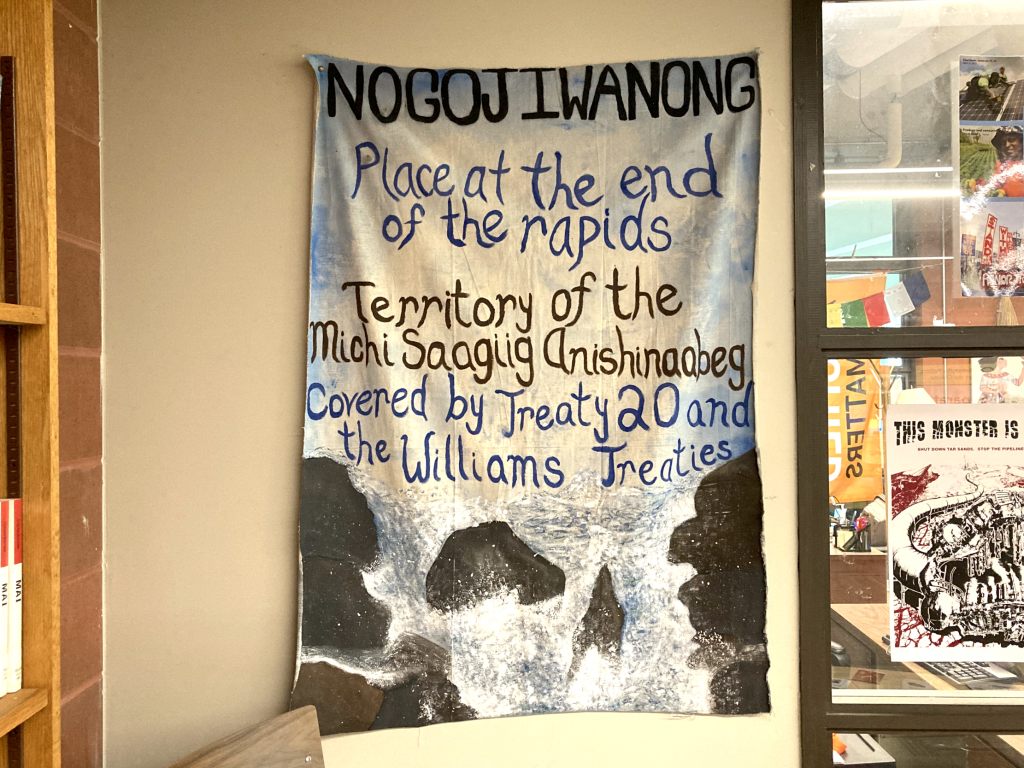

Often, it is society’s poorest and most vulnerable people that are most exposed to environmental harm. This injustice is the subject of much research, but getting the evidence needed to bring about major change can be challenging. Dr Stephanie Rutherford, at Trent University, and Dr Michael Classens, at the University of Toronto, have teamed up with two local organisations in the Canadian city of Nogojiwanong/ Peterborough to document the relationship between social vulnerability and environmental risk in the area, with the aim of driving policy change.

Talk like an environmental justice researcher

BIPOC — Black, Indigenous, and people of colour

Demographic — statistics related to communities or populations, such as age, race or income

Environmental harm — damage to the environment (that typically also damages people)

Environmental risk — the likelihood or vulnerability of an environment (and people) suffering harm

Racialisation — the process by which people and groups of people are defined by their race in ways that privilege or disadvantage them

In Canada, the long shadow of colonialism is felt in persisting environmental injustices. These injustices are not always immediately obvious but can have a serious impact on health and wellbeing over multiple generations. Dr Stephanie Rutherford and Dr Michael Classens are exploring environmental injustices in the town of Peterborough, in Ontario, Canada, by collecting and analysing a range of data that demonstrates these inequalities. Peterborough is also known as Nogojiwanong, which means ‘place at the end of the rapids’ in Anishinaabemowin, the Indigenous language of the territory.

Peterborough has a strong activist history, helping to connect the dots between research and action, so Stephanie and Michael are not working alone. “We have teamed up with two partner organisations which focus on justice, equity, inclusion and environmental access,” explains Stephanie. These organisations are the Community Race Relations Committee of Peterborough (CRRC) and the Kawartha World Issues Centre (KWIC). “These community partners are directly involved in the design, direction and implementation of the research goals,” says Michael.

What is environmental injustice?

“There are decades’ worth of research, especially in the US, that shows a relationship between social inequality and environmental risk or harm,” says Stephanie. “Research in Canada has shown that this is particularly the case for Indigenous communities.” This relationship can manifest in a wide variety of ways.

For instance, vulnerable communities are more likely to live near sources of pollution, such as factories or mines, and have fewer resources, such as access to healthcare, to combat the effects of environmental harm.

“Humanities professor and author Rob Nixon calls this ‘slow violence’,” says Michael. “Long exposure to environmental harms and lack of access to decisionmakers due to marginalisation often leads to accruing effects on health.” For instance, exposure to toxins or pollutants can lead to cancers and respiratory and reproductive diseases, and the effects of climate change, such as flooding and extreme weather events, will disproportionately affect those with fewer resources available to respond. “There are also indirect impacts,” says Stephanie. “A lack of access to green space can affect mental health, water and soil contamination can make communities dependent on others for food and clean water, and a lack of trees in neighbourhoods can increase vulnerability to extreme heat events.”

Data for change

Unsurprisingly, such environmental risks lead communities to believe that decisionmakers do not care about their health and well-being. Getting the authorities to address the situation is often not easy, as communities face the burden of providing evidence to prompt change. For marginalised communities already struggling to meet daily needs, such efforts are out of reach. Stephanie and Michael are hoping that they can address this issue by combining their scientific training with the drive and knowledge of local organisations.

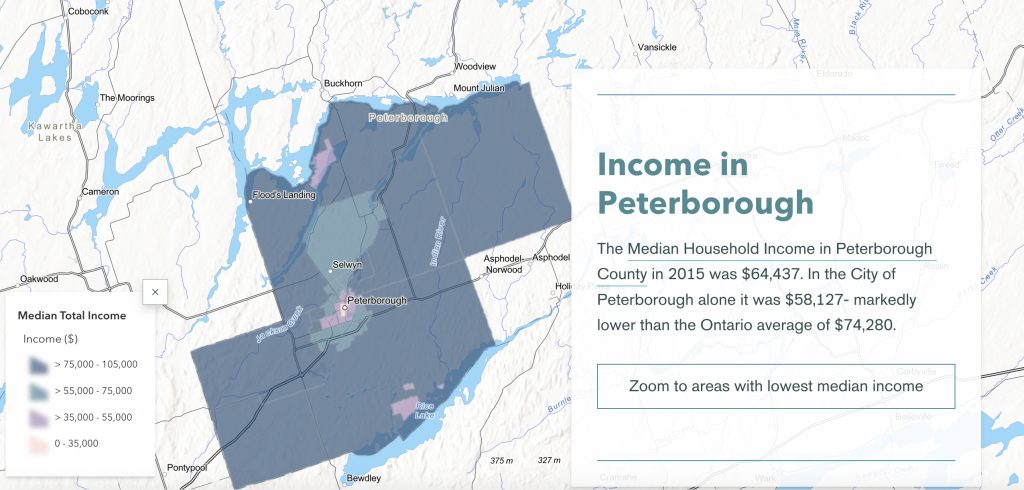

“Peterborough is a small city with a big industrial legacy,” says Michael. “We are interested in exploring the impacts of that legacy on local people.” The team is using quantitative methods, which include mapping exercises, and qualitative methods, such as interviews and photography, to explore these impacts on different demographics – and, most crucially, how interventions can help bring about environmental justice.

Impactful maps

Maps can be powerful tools for visually displaying persuasive datasets. For instance, if a map shows that areas of industrial pollution overlap significantly with the residencies of marginalised communities, this is compelling evidence of environmental injustice. “Being able to demonstrate the disproportionate burden shouldered by some groups provides the kind of proof that decision-makers are looking for in terms of policy development,” explains Stephanie. “Maps make it difficult to ignore these relationships.”

To collect such spatial data, the team first turned to government data sources about environmental issues such as contaminated sites, polluting facilities, landfills and climate vulnerability. “We mapped these data against demographic data covering variables such as race, income, education, and people with disabilities,” explains Michael. “This helped us build an index of vulnerability to see who experiences the most environmental risk in Peterborough.”

The team found that government data was insufficient for its needs – some of it was not at a fine enough scale, and some data did not exist at all. “For example, there were no data on waterborne illnesses on First Nations reserves – a huge issue because many communities do not have access to clean drinking water,” says Stephanie. Stephanie and Michael are now assessing how they can collate their own datasets, to use in their own project and to share with local social and environmental organisations.

The power of stories

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM503

© KWIC Staff

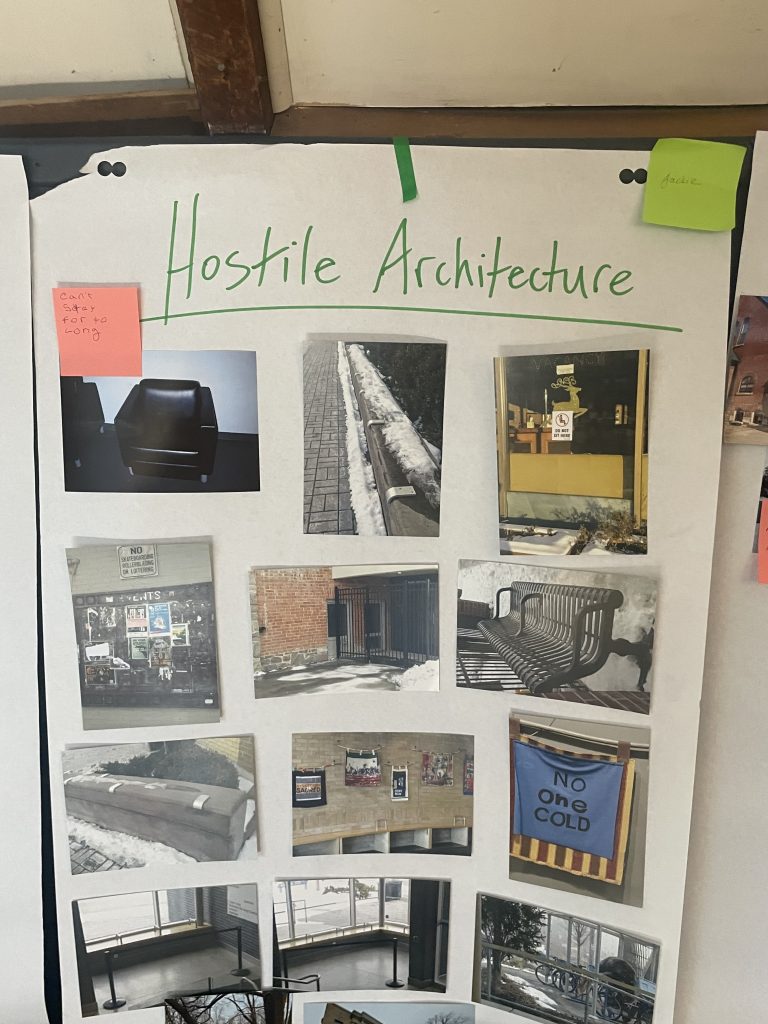

Quantitative data are powerful, but they never tell the whole picture. While hard data are useful for policy makers, understanding what such data mean at the personal level – for the people impacted by environmental injustice – is vital. “Through interviews and oral histories, we are supplementing the map with stories of people’s lived experience of environmental risk and harm,” explains Michael. “We also have a project that invites community members to take pictures of the environmental goods and bads that they experience every day, which makes for striking visual evidence.”

The aim is for this combination of quantitative and qualitative data to tell a fuller picture of the situation to policy makers, strengthening the case for change. The data will also be publicly available. “We are making a freely accessible living digital archive of data, maps, images and stories,” says Stephanie. “A core principle of this project is that the data should be available to anyone who wants to use them.”

Evidence of injustice

The Mapping for Change project has already unveiled some serious instances of environmental injustice in Peterborough. “In our mapping work, we are finding that poverty is a key indicator of exposure to potentially harmful contaminants,” says Stephanie. “People living on former industrial sites tend to have lower incomes and a higher proportion of lone parent households.” Through interviews with former industrial workers, the team has documented occurrences of occupational diseases – illnesses such as cancers that have arisen due to exposure to toxins during their work. “In our photography work, we are also exploring how people experience environmental justice,” says Michael. “We are developing themes such as the privatisation of space, impacts of industry, and the lack of accountability from those responsible for causing environmental harm.”

The team is now readying to release their map to the public. “We anticipate that it might generate a lot of questions, both from community members and local politicians,” says Stephanie. “We plan to write policy briefs that highlight key results for the government, as well as communicate our results to the public through infographics, fact sheets and newspaper articles.”

The project has also built its own community. “Through sharing photos and talking openly about personal experiences, the participatory element of our research is building solidarity among the group,” says Michael. “We are lucky to be able to learn from individuals and community organisations acting for change.”

The pathway to change

The team hopes that municipal and government authorities will take notice of the results and acknowledge the environmental injustices happening in Peterborough. “The disproportionate burden of environmental harm violates the Ontario Environmental Bill of Rights and the right to a healthy environment under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act,” says Stephanie. “Government needs to acknowledge this and help bring about the change needed.” Data that the team has collected not only demonstrate the problems but can also be used to generate solutions. “We would like these data to lead to real and lasting policy change at a variety of levels,” says Michael. “Most crucially, we need structural change and better access to decision-making for these vulnerable communities.”

Now, Stephanie and Michael are planning to supplement their map with further data, gathered through their own efforts. “We are planning to test for contaminants in the soils of former industrial sites,” says Stephanie. “We also have a project which will explore the colonial impacts of the Trent Severn Waterway as a form of environmental injustice.” This waterway is a 240-mile-long canal, whose construction disrupted Indigenous practices and led to dispossession of land, but whose long-lasting impacts are not fully understood.

Public access remains at the heart of the team’s work. “We are developing a photography exhibition to showcase the amazing images captured by our research participants,” says Stephanie. “We are also working with academics and community organisations to host a data symposium on the need to produce and analyse locally-relevant data to promote social and environmental change.” By building these connections, future efforts can use these collaborative networks to kick-start further research and interventions for environmental justice.

Dr Stephanie Rutherford

Dr Stephanie Rutherford

Associate Professor, School of the Environment, Trent University, Canada

Funders: Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), Symons Trust Fund for Canadian Studies

Dr Michael Classens

Assistant Professor – Teaching Stream, Faculty of Arts and Science, School of the Environment, University of Toronto, Canada

Funder: Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC)

Fields of research: Communities and cities, food and agriculture, social and environmental justice, social sustainability

Research project: Mapping for Change: Environmental Inequality and Resilience in Nogojiwanong/Peterborough – mapping the landscape of environmental justice and how people and communities are organising to address it

About environmental justice

There are plenty of environmental issues in the world, and these often have a negative effect on people’s health and well-being. However, they do not affect all people equally. Environmental justice research aims to examine the inequalities in how people are affected by environmental harm, and what demographic differences lie at their heart. Typically, environmental injustices are closely tied to social injustices – and addressing both simultaneously is critical to building a fairer world.

Understanding environmental injustice involves understanding the experiences and perceptions of those affected. “Environmental justice research gives us the opportunity to work with and learn from community members who have lived experience of environmental risk,” explains Stephanie. “In our research, they have taught us so much about the inequalities that shape our community. As university professors, our privilege often insulates us from this.”

As environmental issues evolve over time, environmental justice will remain a key area of research. “For instance, the unequal burdens of climate change will continue to be an area in need of a lot of research,” says Michael. “As the impacts of climate change worsen, researchers will need to pay close attention to how these impacts are distributed.”

Stephanie and Michael emphasise that environmental justice research involves an understanding of both social and environmental perspectives. “A good grasp of both the scientific and social dimensions is key to finding solutions to environmental problems,” says Stephanie. “Research in the field typically involves interdisciplinary teams of environmental and social scientists.”

Meet Stephanie

I am a social scientist. My work explores the intersections between the environment and social inequalities, such as racism, classism, sexism and colonialism. I also work on human-wildlife conflict, thinking about how human changes to the environment impact animal populations, which is also a form of injustice. I have always been a scholar who wants to see justice in the world – both for humans and nonhumans. This inspires all my work.

I grew up in a working-class community in Toronto. There was a lot of industrial activity, combined with a lack of green space. This prompted me to think about how power – and access to power – shapes the kind of environmental risks people experience.

My proudest career achievement is the Mapping for Change project. It has the potential to have tangible, real world impacts for the community I live in. I think it is really important to pay attention to the challenges of where you live, and I seek to do research that changes those conditions.

I would like to see the Mapping for Change project expand beyond Peterborough. Other former manufacturing towns in Ontario, including Hamilton, London, Oshawa, Sarnia, Sudbury and Windsor, are all part of a larger story about the environmental impacts associated with industry. This much bigger project would involve academics and community partners in each of these communities.

Stephanie’s top tip

Keep asking questions about why things are how they are. Young people are so important for holding older generations to account on issues like climate change. Use your education to back up your demands for change with actionable data.

Meet Michael

In high school, I did a project on industrial chicken farming, and it was a revelation to me. I learnt how socially unjust, environmentally destructive and ethically fraught industrialised agriculture is. My career has been shaped by working with communities and people engaged in struggles for social and environmental justice.

I work with so many incredible people. I’m very grateful to have the opportunity to work with so many fantastic organisations, students, staff and colleagues at the University of Toronto, and beyond. I hope to continue to have the opportunity to work with dedicated and passionate people who are engaged in work to realise a more just and sustainable world.

Michael’s top tip

The two feminist economists (who share the pen name) J. K. Gibson-Graham talk about ‘here and now’ as the best starting place for the fight for change. In other words, start where you are with what you have, and go from there. And always make room for hope and joy!

Community partners

Stephanie and Michael partnered with two community organisations for their Mapping for Change research. This access to community connections and expertise allowed them to focus their research on people with lived experience of environmental justice – people who are often absent from academic research. Understanding the perspectives of these people is vital to addressing environmental injustice.

Community Race Relations Committee of Peterborough (CRRC)

Patricia Wilson

Coordinator, Community Race Relations Committee of Peterborough, Canada

Fields of research: Anti-racism, institutional and systemic discrimination, public education, human rights, diversity, environmental justice

Funders: Ontario Trillium Foundation, City of Peterborough, Trent University

CRRC is a community-based non-profit organisation, committed to promoting positive race relations in Peterborough, Ontario. Its activities include community-based advocacy, collaborations, and education. Patricia Wilson, CRRC’s Community Advocate & Outreach Coordinator, explains more.

“Stephanie and Michael approached CRRC in 2021, asking us if we were interested in collaborating on the Mapping for Change project. We signed on as a lead partner because the project’s work fits squarely in our mandate.

“CRRC is a central member of the project’s advisory committee. We weigh in on decisions and help to shape the project’s direction. We are also responsible for anti-oppression training for all research team members.

“Seeing the map of environmental risk and social vulnerability take shape has been great. It will be a tangible visualisation of the ways in which race, class and environmental risk intersect.

“We want to see real change come from this research; the results should work for the community. We think that the map, the photovoice images, and the oral histories will help tell the story of environmental justice in this community in a way that prompts – or forces – policy-makers to address inequities.

“We lead a range of initiatives and programming that help to address and combat racism in Nogojiwanong/Peterborough. Last year, we ran a research project that explored the impacts of racism and racialisation on BIPOC community members. It’s particularly focused on the impact of COVID-19 on Peterborough’s BIPOC communities and the emerging needs that have come from the pandemic aftermath. CRRC will use this research to inform the development of services that better meet the needs of racialised individuals in our community, help inform the strategic direction of the organisation and act as community research that can be used to inform policy and be leveraged by organisations to access more funding and support to better address BIPOC community needs.”

Kawartha World Issues Centre (KWIC)

Sam Rockbrune

Executive Director, Kawartha World Issues Centre, Canada

Fields of research: Socio-legal studies, gender equality, campus sexual violence, law, intersectionality

KWIC is a charitable organisation that connects global issues to local initiatives. It aims to create opportunities to change perspectives and foster equitable and sustainable communities, through community education, programmes with youth and schools, and umbrella support for small and emerging initiatives. KWIC’s Executive Director, Sam Rockbrune, explains more.

“KWIC has a 35-year history in Nogojiwanong/Peterborough. We have developed a strong reputation for being a community connector and for working on global issues such as climate and environmental justice. The Mapping for Change project recognises the importance of community organisations, given we often understand best what is happening on the ground and have strong connections with community members.

“I provide overall leadership to our team. As a partner on the Mapping for Change project, we support the project steering team in its decision making, such as suggesting pathways for research to be shared with youth. I have also facilitated training sessions with the research team, and KWIC has shared calls for participants and updates on the research. When final results are in, we will help ensure they are shared with the community.

“For me, the biggest highlight of the project has been delivering training. I facilitated a workshop on Popular Education and Best Practices and enjoyed spending a few hours with the researchers to hear more about the project’s details, and share KWIC’s experiences and knowledge for driving impactful conversations.

“I’m hoping this project will be a turning point. I want it to open doors for more work on environmental injustice, especially for racialised communities. One of the project’s many objectives is tangible change, so seeing leaders make decisions based on the project’s findings would be phenomenal.

“We facilitate many projects to encourage and support young changemakers in our community. In Spring 2024, our Returning to Mother Earth, Gender Equality (SDG5) and Climate Action/Justice (SDG13) workshops will start, and we are hoping to offer mentorship and leadership programmes for young changemakers. 2024 is also our 35th anniversary, so we will celebrate by bringing the community together!”

Sam’s career

“I didn’t have a plan in mind to get to where I am now. When I graduated high school, all I knew was that I wanted my career to make a difference and pay my bills! At 17 years old, I decided law was the way to go, and while I’m not in that field now, both my degrees and the experiences they entailed led me to my current role.

“Finding a community of like-minded individuals has been pivotal. Having peers who want to make a difference and who also encouraged me to step into leadership roles, has been fundamental to where I am now. As a racialised woman, I am beyond grateful for the many other BIPOC women and non-binary folks who built this community with me.

“Now as a leader and changemaker, I really appreciate the lessons every organisation and experience taught me, especially the community members who practise care, kindness, joy, and giving yourself a break when you need to as central to social justice work.”

Sam’s top tip

Find your community. Social and climate justice work can be difficult and lonely at times. You’re working against big, global, interconnected problems, and, sometimes, having someone send you a silly meme or backing you up in a meeting can make all the difference and encourage you to continue.

Pathway from school to environmental justice research

Stephanie and Michael highlight how important an interdisciplinary approach is. They recommend studying subjects such as biology, chemistry and environmental health, alongside geography, social studies, economics and political science.

Universities offer undergraduate courses in subjects that can explore or relate to environmental justice, such as environmental science, geography, law and social studies.

Explore careers in environmental justice

Trent University, where Stephanie works, hosts an Enrichment Program for high school students, which includes courses on environmental issues. The university also hosts the annual Peterborough Regional Science Fair, which provides an engaging and practical entry into science and technology.

The University of Toronto, where Michael works, hosts Youth Climate Action Toronto, which supports young people in developing strategies for youth engagement in climate action.

ECO Canada has a broad range of resources, including training and education support, for those looking to work in the environmental field in Canada.

According to Glassdoor, the average salary for an environmental researcher in Canada is around CAN $55,500 per year.

Do you have a question for Stephanie, Michael, Patricia or Sam?

Write it in the comments box below and Stephanie, Michael, Patricia or Sam will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

Read about a community-driven research project is assessing air pollutants:

www.futurumcareers.com/combining-science-and-community-action-to-combat-environmental-injustice

0 Comments