How and why do governments forget?

We all tell stories about past events, and people working in government departments are no exception. These stories cause knowledge to be passed on between different generations of employees, allowing departments to learn from the successes and failures of the past. However, what happens when these stories are lost from memory? Associate Professor Alastair Stark, Professor Heather Lovell and Professor Rodney Scott are working on an international collaboration to unpick how an organisation’s memories of the past can influence the policies made in the present.

Talk like a public policy researcher

Institutional amnesia — when an organisation forgets knowledge it used to possess

Institutional churn — the turnover of staff in an organisation as existing employees leave and new ones are hired

Institutional memory — the collective knowledge of past events held by an organisation

Policy — a course of action adopted by an organisation. Public policy refers to policies created by governments

Policymaker — a person responsible for developing policies

Public servant — a non-elected person who works for the government, i.e., not a politician

Public service — the sector of government containing departments that serve the needs of the public, known as the ‘civil service’ in some countries

The most important role of any government is to create and uphold public policy. These policies form the backbone of a nation, by setting the rules to support and protect the country and its citizens. However, what factors influence the policymaking process? How do changes within government departments impact the policies these departments create?

An international team of academics, including Associate Professor Alastair Stark at the University of Queensland, Australia, Professor Heather Lovell at the University of Tasmania, Australia, and Professor Rodney Scott at the Te Kawa Mataaho Public Service Commission of New Zealand, is hoping to answer these questions by investigating how changes in institutional memory affect public policy processes.

What is institutional memory?

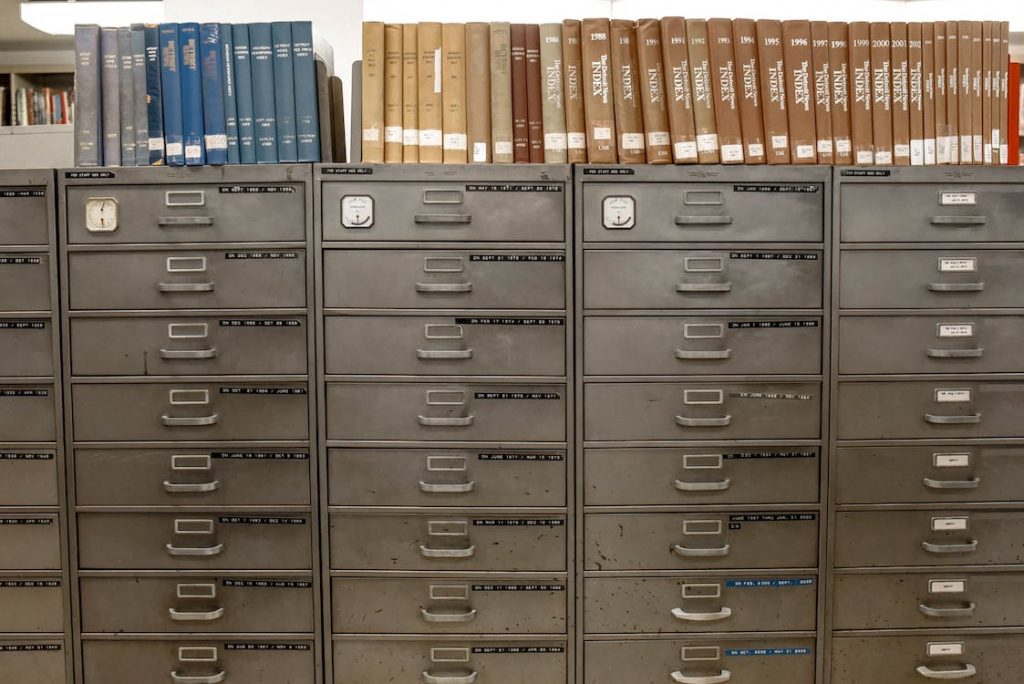

“Institutional memory is the knowledge of the past that is held by organisations,” says Heather. “This includes both formal knowledge, archived in documents and files, and informal knowledge that is held in people’s heads.” This informal knowledge commonly involves stories of the organisation, perhaps discussed in meetings or shared as gossip over lunch. It is much harder to pin down this informal knowledge to study it, as it does not exist in any physical form and its dynamic nature means these stories are constantly changing as they get passed from person to person. In contrast, reports of an organisation’s past actions are recorded and filed away, so formal institutional memory tends to remain static.

The team believes that dynamic, informal institutional memory is just as important in the decision-making process within organisations as official records of the past. “The theory is that these two different types of institutional memory – formal, static memory and informal, dynamic memory – have different effects on policymaking processes,” says Al.

How does storytelling influence memory?

“Storytelling uses narratives to represent the past in a particular way,” explains Heather. “Within governments, storytelling might involve passing on information about the nation’s cultural traditions or using metaphors that simplify complex processes for newer members of staff.”

However, this informal method of transferring information is not always reliable. “Storytelling is a representation of the past, but stories don’t necessarily tell you exactly what happened, or all of what happened,” explains Rodney. While stories can provide a wealth of information, key details of true events are likely to be misremembered or changed through time. “When studying storytelling, it’s important to understand what happened, how this was interpreted and remembered by the people there, and how these memories are passed on through stories.”

What role does institutional churn play?

One key factor affecting institutional memory is the turnover of staff, known as ‘institutional churn’. When staff members leave, they take their memories of the organisation with them. Once all the employees who remember ‘how things used to be done’ have left, these stories will no longer be told in the lunchroom and that knowledge will have faded from institutional memory. When institutional memory is lost, it can result in ‘institutional amnesia’, causing organisations to forget knowledge of policymaking and policy processes.

How does churn vary between governments and departments?

To date, most academic research has been focused on institutional churn in corporations, but the team wants to understand more about churn in governments. “We have analysed data on churn in government departments in Australia, New Zealand and the UK, going back to the year 2000,” says Heather. The initial results have shown some interesting similarities and differences between nations and departments.

For example, churn is lower in the Australian Public Service than in the New Zealand Public Service and the UK Civil Service. Transfers between departments are particularly high in the UK Civil Service, as employees are routinely moved between different government departments. In all three countries, the Prime Minister’s cabinet is associated with the highest rates of staff turnover while the department responsible for foreign affairs has the lowest rates of turnover.

How is the team investigating the impact of churn?

After analysing data on the extent of churn in the Australian, New Zealand and UK governments, the team is now digging deeper to understand government employees’ attitudes towards this churn. “We have developed a survey to find out what respondents think about how turnover has affected the ability of their organisation to remember the past in relation to current policy,” explains Heather. Following the survey, the team will carry out interviews with government employees to gather further information that cannot be captured with a written questionnaire and conduct case studies with public service agencies in these three countries to uncover what influences memory in each institution.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM355

Public policy researchers share their findings with governments and multilateral organisations. In May 2022, Rodney discussed churn and institutional memory with the Public Employment and Management Committee of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in Paris.

What does the team expect to discover?

Although Al, Heather and Rodney are still in the early stages of their work, other researchers have speculated that institutional churn may have both good and bad effects on policymaking. “Churn can cause a loss of institutional memory, but can also bring new ideas to an organisation,” says Rodney. “In the case of people moving between government departments, key insights can be transferred and spread across the civil service.” In this project, the team hopes to test these ideas to establish exactly how institutional churn influences institutional memory and therefore policymaking processes.

“At a simple level, it is likely that some churn is good, but too much is bad,” says Rodney. “However, it may be more complicated than that, and churn may have different effects in different situations.” For instance, churn among senior members of staff may have different effects to churn among non-managers, as employees at different levels may hold different types of institutional memory. If turnover is gradual, with staff replacement only happening every now and then, stories can be passed on to new employees as they arrive, and so institutional memory will linger. However, if everyone in a team leaves at once, there will be no one left to teach the new team about the department. “Providing evidence for these sorts of insights will help us make recommendations to public servants about how to manage churn more effectively,” says Al.

How is the team investigating the impact of storytelling?

The team will use a method called ‘thick descriptions’ to unpick the influence of storytelling on institutional memory. “Thick descriptions combine empirical descriptions (objective descriptions of what happened), with the remembered experiences of public servants, and their personal interpretations of what happened and why,” says Rodney. This will provide rich data for the team to analyse and make conclusions about the reliability of informal memory and what this means for policymaking.

“We expect to find that stories from the past have a strong impact on behaviour and decisions in the present,” says Al. “It is likely that these stories sometimes have positive effects, sometimes have negative effects, and sometimes have both at once.” Storytelling is an effective way of passing on what has been learnt in the past so this knowledge can be applied to inform current decisions. However, if the context in which these lessons were learnt is different from the context in which they are being applied today, it may not be appropriate to use this knowledge as it could result in unintended outcomes. “We want to find out how, why and when stories have these different impacts,” says Rodney. “This will help us advise policymakers on how to use these stories effectively, allowing them to keep the good effects while minimising the bad.”

Influencing policy

The team’s research will only be useful if it is effectively communicated back to policymakers, so working closely with public service agencies is a key aspect of the project. The team will share their discoveries with the departments involved in the study, providing them with specific advice and helping them to learn from the results of the project.

“Beyond that, we will also engage with the central agencies of each nation to provide more general advice on how best to manage churn and institutional memory,” says Al. “Central agencies exist at the centre of governments and are responsible for creating the policies that define how all the other agencies work, so this will help our project make a difference far beyond the agencies involved in our case studies.” The team’s research will therefore be useful for governments around the world, ensuring they do not forget crucial knowledge as staff members change and allowing them to learn from the successes and failures of past policies.

Associate Professor Alastair Stark

Associate Professor Alastair Stark

Associate Professor of Public Policy, School of Political Science and International Studies, University of Queensland, Australia

Professor Heather Lovell

Professor of Energy and Society, School of Social Sciences and School of Geography, Planning, and Spatial Sciences, University of Tasmania, Australia

Professor Rodney Scott

Chief Policy Advisor, Te Kawa Mataaho Public Service Commission, New Zealand

Adjunct Professor, University of New South Wales, Australia

Field of research: Public Policy

Research project: Investigating the effects of institutional memory on policymaking decisions

Funder: Australian Research Council (ARC), Project number DP210100149

ABOUT PUBLIC POLICY

“Public policy is fundamental to everyday life,” says Heather. “How a government decides to act affects everyone, directly or indirectly.” Public policy is everywhere, affecting how nations approach issues as diverse as energy usage, healthcare and business.

While policies are implemented by policymakers working in government departments, they are studied by researchers in academic institutions to investigate whether they are effective at addressing the issues they are aiming to solve. All research findings must be communicated back to the policymakers, to ensure policies will benefit society.

“Public policies are, broadly speaking, the sum total of government action,” says Rodney. “They address a vast range of topics, covering anything that the government works on, from housing to tax to the environment.” Policies are made by both national and local governments, and international policies are drawn up and enacted as a result of countries working together.

The policy cycle

The process of policy development is known as the ‘policy cycle’, which describes the different stages of defining the issues to address, drafting and reviewing the policy, implementing the policy in society and evaluating its performance. “The process of developing policies is continuous and, in most cases, pretty slow,” says Al.

Researchers study the policy cycle to help policymakers understand which parts of the process work well and which parts do not lead to effective public policies. By combining the knowledge of academics and policymakers, the process of developing and implementing public policies can be improved.

Crossing disciplinary boundaries

Public policy research can be interdisciplinary. In this research project, although most team members are political scientists, the team combines theories and methods from many different disciplines, including human geography, anthropology, sociology and psychology, to address the questions surrounding institutional memory. Each team member contributes their own set of skills and expertise to the project.

For example, as a human geographer, Heather brings concepts of how policy ideas move from place to place, which can be applied to consider how stories about the past move within and between different government departments. As a policy practitioner, Rodney brings a wealth of ‘hands-on’ experience to the team.

Pathway from school to public policy

• At school, Heather recommends studying a mix of science and social science subjects. “Sciences will enable you to understand and translate technical knowledge, while social sciences will allow you to appreciate different viewpoints, synthesise diverse knowledge and write clearly,” she says.

• At university, degrees in public policy, political science, sociology or human geography could all lead to a career in policy research or implementation.

Explore careers in public policy

• If you are interested in analysing public policies you could become a researcher, while if you are interested in implementing them you could become a policymaker. Or, if both analysis and implementation appeal to you, you could do both, like Rodney.

• Find out more about careers as a policy analyst, including the skills you need and the work you can expect to do, from the Australian Government (www.yourcareer.gov.au/careers/224412/policy-analyst), the New Zealand Government (www.careers.govt.nz/jobs-database/government-law-and-safety/government/policy-analyst) and the UK Civil Service (www.civil-service-careers.gov.uk/professions/working-in-policy).

• The Mandarin, an Australian news organisation, has a section dedicated to careers in the public sector: www.themandarin.com.au/career-advice

Meet the team

Associate Professor Alastair Stark

Field of research: Public Policy

I grew up in a context of social exclusion, in a challenging environment with a variety of problematic behaviours. When it comes to learning, everyone is different. I hated the rigid nature of school and being told what to learn and how to learn it. I therefore failed as a school student.

I left school as soon possible, with no qualifications. I got a job via a government programme (a public policy) designed to give young people with no qualifications the chance to gain work experience and a college certificate. This public policy changed my life.

I worked in local government and went to college one day a week, where I learnt how governments continually try (and fail) to address social problems. This enabled me to go to university to study politics and public administration, which was revelatory. I came alive as a learner because I was given the independence to learn in ways that worked for me.

Learning about policy was like opening a door – I could now explain all the things that surrounded me: the problems I personally faced, the larger societal issues that created my environment, and how government policies tried to fix them. I learnt why my everyday experiences looked and felt the way they did and so understood my personal world much more effectively.

After this, I never looked back. I had a career in government then a career in researching government. The goal of public policy research is to improve how governments respond to the problems all around us. My primary interest is in crisis management policies, and I’ve had the satisfaction of working with the Australian government to ensure we learn (and don’t forget) lessons from crises.

Teaching students about public policy is undoubtably the most rewarding part of my job. I enjoy showing students how their surroundings have been shaped by government policies and how they can influence policies for the collective good. Many of my students go on to work in government, and, years later, many tell me they still use the lessons I taught them in their careers.

In my free time, enjoy collecting sci-fi novels and, although no one ever gets to read them, writing sci-fi short stories. I have an unhealthy obsession with dystopian futures, zombies and steam punk!

I have never forgotten it was a public policy that gave me the opportunity to escape my context, and that studying policy opened the world up to me. That is why I study public policy – because policies can change lives. They changed mine.

Alastair’s top tips

1. Don’t be afraid to fail. And never let your failures convince you that you are a failure.

2. Try many things, fail many times, and, when you find your passion, work hard at it and seize any opportunities that come your way.

Professor Heather Lovell

Fields of research: Human Geography, Sociology, Public Policy

In this project, I am leading one of the detailed case studies looking at energy policies in Australia. I studied human geography at university, and this has allowed me to work a lot with policy processes. I’m most interested in how policies travel from place to place.

Most of my research investigates energy and climate policies. Over the past decade, I have been studying smart grids – electrical networks that intelligently balance supply and demand to maximise efficiency. I’m interested in how policymakers create policies for totally new and complex concepts such as smart grids.

I enjoy how varied my work is. On any given day I could be working on many different things – contributing to research projects, teaching students or participating in committees. No two days are the same! I really enjoy seeing patterns in research across different disciplines. For example, I realised that political scientists are studying very similar processes to some human geographers, just using different terminology. Making these connections can help draw together insights from different disciplines and progress our cumulative knowledge.

I’ve had many excellent mentors throughout my career, especially during my PhD and first postdoctoral research jobs. They all happen to have been women, and I think that was important for me to learn how to navigate academia as a woman.

In 2014, I was fortunate to be awarded a grant from the Australian Research Council to research smart grids in Australia. I’m originally from the UK, so this opportunity to move across the world and experience a different way of life has been a real highlight.

As a young child, I loved finding out about plants and animals. My brother and I would spend time collecting snails and ladybirds. I loved spending time outdoors and seeing the seasons change, as well as reading stories. These days, I still enjoy being outdoors in my free time. I like walking our dog and running on the many mountain paths that are right on our doorstep in Hobart, Tasmania.

Heather’s top tips

1. An academic career is very rewarding, but hard work. Try not to compare yourself with other people.

2. The culture of long working hours in academia can be tricky to navigate if you have caring responsibilities, such as children. But remember that good ideas do not necessarily take a lot of time to generate.

Professor Rodney Scott

Field of research: Public Policy

I work in the New Zealand Public Service as the Chief Policy Advisor. In this role, I support the Public Service Commissioner (the head of the New Zealand Public Service) by providing advice on the design and direction of public services. This involves traditional policy analysis and engaging with research communities and international practices.

I have worked for many years on how public institutions can make better use of institutional memory and learn lessons from past experiences. My work in the New Zealand Public Service means I bring insights as a public servant to this research project. These insights help the team think about how to make our findings useful and practical.

I’m fortunate to be involved in both policy research and implementation. I enjoy the intellectual stimulation of academia and seeing how these findings are applied to make a difference to New Zealanders.

I never thought I would end up in public service or academia. I started out working as an osteopathic doctor, then moved into managing the operations of several health charities. Every step of my career has felt like moving further from the people I’m trying to help, but at the same time helping a greater number of people. I wanted to explore topics in greater depth, which led me to work more closely with academics to support better policy advice.

I am fascinated by aspects of public administration, such as public ethics, political neutrality, stewardship and public participation. While both public and private sector administration involve managing resources to deliver goods and services, the factors I am interested in are not fundamental in the private sector. I am also very interested in public service motivation, what we call ‘te hāpai hapori’ in New Zealand, or ‘a spirit of service to the community’. Why do some people feel a calling to serve their community? How can we protect and nurture this spirit?

Passing the Public Service Act 2020 was a career highlight for me. This was a once-in-a-generation change to protect the integrity of the public service and to make it more effective for years to come. Another highlight was establishing the Public Service Fale, for which I got to work with inspiring leaders from across the Pacific. The Fale is a new function to help 16 Pacific Island Nations strengthen their own public services.

Growing up in Australia, I loved sports and music. I played Australian-rules football, cricket and basketball. I also played the piano in a few terrible cover bands. These days, I still enjoy sports and music in my free time and I also enjoy travelling. My work has taken me to dozens of countries, and I love learning about different cultures and ways of life.

Rodney’s top tips

1. Never stop learning. Every step of my career has involved learning new skills.

2. Keep an open mind about what you like and what you feel you are good at. This will change over time.

3. Focus on making a difference. It is the impactful moments that I look back on and that keep me motivated.

Write it in the comments box below and Al, Heather or Rodneywill get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)