How are coercive psychiatric practices experienced by First Nations communities?

While psychiatric services are designed to help people with mental health issues, they do not benefit everyone, and many people are held in psychiatric facilities against their will. Not only are people from Indigenous communities more likely to be held in psychiatric facilities, but mental healthcare approaches based on Western ideas of health and illness do not provide suitable healing for people with different worldviews. At the University of Ottawa in Canada, Professor Emmanuelle Bernheim and Professor Eva Ottawa are investigating the effects of coercive psychiatric practices on Manawan community members and helping them develop their own well-being and territorial programme.

Talk like a social justice researcher

Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok — a First Nations people who live in the Manawan community

Coercive — the use of force or threats to get someone to do something against their will

Colonise — to settle among and take control over Indigenous Peoples and their lands

First Nations — Indigenous Peoples of Canada

Medicine wheel — a symbol in various First Nations cultures representing the interconnections between all living things

Miromatisiwin — an Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok term meaning ‘to have a good life with the world around us’ or ‘to live a life of balance and harmony’

Ontology — the philosophical study of the nature of existence

Psychiatric — related to mental illness

Sedentary — staying on one place

If, due to the state of their mental health, someone is considered to be a danger to themselves (or others), they can be admitted to hospital and kept there against their will. While this confinement is designed to protect the person concerned, it can have severe negative consequences on them. What is more, research from Australia and New Zealand has shown that people from Indigenous and marginalised communities are disproportionately subjected to coercive psychiatric confinement, highlighting how such practices are exacerbating social inequalities.

“The only Canadian study on the subject, conducted in the 1990s, showed that on average, First Nations people in Canada are held in psychiatric hospitals for twice as long as other patients,” says Professor Eva Ottawa, a member of the Manawan community and a specialist in Indigenous law at the University of Ottawa. She is working with Professor Emmanuelle Bernheim, a civil law and social justice researcher, to investigate the impacts of coercive psychiatric practices on members of the Manawan community. They are also working with community members to develop well-being approaches that align with community values and worldviews.

Manawan mental health challenges

The Manawan community is located 250 km north of Montreal, in the Canadian province of Quebec, and is home to around 3,000 Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok. “The Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok consider themselves intrinsically linked to notcimik, the forest universe, which has shaped their way of life,” explains Eva. Before colonisers arrived in the region, the Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok lived a nomadic lifestyle, moving around their ancestral territory according to the six seasons and sustaining themselves through hunting and trapping. The violent impacts of colonisation included the creation of the Manawan reserve in 1906, which forced the Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok to adopt a sedentary lifestyle on the small area of land allocated to them by the Canadian government.

Today, the Manawan community faces numerous mental healthcare challenges due to a lack of mental health services. Most hospitals or crisis centres have specific rooms to ensure a patient’s safety during a mental health crisis, with caregivers on duty at all times to monitor them. However, there is no crisis room in the Manawan Health Centre and there is not always a doctor or psychiatrist on site. This means community members cannot always access local services during certain crisis situations.

“Vulnerable people have nowhere to turn during mental health crises,” says Emmanuelle. Instead, they are forcibly hospitalised. However, psychiatric confinement is resented by those who experience it, who view it as a coercive, rather than caring, measure. In 2020, 39 people from the Manawan community were transported by the police to the emergency room of the hospital in Joliette (185 km away). “The overuse of such practices against members of the Manawan community is a clear case of systemic discrimination,” says Eva.

Uncovering coercive psychiatric practices

Emmanuelle and Eva’s research is focused on involuntary admission to emergency rooms and psychiatric wards as a form of coercive psychiatry. To investigate the issue, they are collecting data from multiple sources covering all stages of the process. “We want to document police and hospital practices alongside community members’ experiences,” says Emmanuelle. “This involves compiling medical records, conducting interviews with health professionals and police officers, and meeting with individuals who have been forcibly hospitalised and their families.”

While the research is still in its early stages, the team has already noticed a worrying lack of follow-up care for psychiatric patients. “It appears that several individuals have simply ended up on the streets after being discharged from the hospital in Joliette and left to find their own way back to the Manawan community,” says Emmanuelle. Once discharged, patients are not offered further mental health counselling.

Differences in perceiving the world

To address mental health needs, it is essential to understand how people perceive themselves and their place in the world. However, the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric conditions follow Western views of medicine and do not accommodate Indigenous worldviews.

“The Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok subscribe to the concept of miromatisiwin, meaning ‘to have a good life with the world around us’ or ‘to live a life of balance and harmony’,” says Eva. This ontology, or theory of being, is very different to that found in Western cultures, where humans are considered separate from their surroundings. “The Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok ontology encompasses a vision where values, experiences and relationships are a core part of reality. This way of being encompasses a sense of responsibility towards others, both human and non-human.”

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM456

Images © Thérèse Ottawa, CC BY-SA 4.0

These differences in the ideas of our place in the world inevitably lead to fundamentally different approaches to life. The lack of interconnection between self and others in Western mental healthcare makes it unsuitable for people with different theories of reality. Emmanuelle and Eva’s project aims to document practices and experiences related to the use of involuntary admission in the Manawan community and to support the community in the development of wellness services.

Miromatisiwin services

Together with the Manawan community, Emmanuelle and Eva are co-developing an array of miromatisiwin wellness services, which embed Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok knowledge. These therapies will draw on Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok ontology linking individual health to territorial health. “The Manawan Health Centre has already experimented with a mental health support programme that encourages close contact with the land,” says Eva. “It includes ceremonies with community elders, allowing beneficiaries to undertake the sacred journey of their lives thanks to the medicine wheel, and promotes daily use of the territory through traditional activities such as hunting and trapping, to help bring about personal balance.”

Emmanuelle and Eva hope that the community-led miromatisiwin services will improve mental health and well-being among Manawan community members, reducing the number of people subjected to damaging coercive psychiatric practices.

Professor Emmanuelle Bernheim

Professor Emmanuelle Bernheim

Professor Eva Ottawa

Faculty of Law, University of Ottawa, Canada

Fields of research: Social justice, mental health, law

Research project: Investigating coercive psychiatric practices against Manawan community members and co-creating community-aligned well-being services

Funder: Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC)

About psychiatry and law

How have psychiatry and law been used as colonial tools?

The frameworks behind Western notions of psychiatry are rooted in colonial values, which put them at odds with the values of Indigenous cultures. “For example, the classification of ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ behaviours in psychiatry is based on the cultural standards of colonisers, not of Indigenous communities,” says Emmanuelle. “By prioritising the supposed ‘rationality’ of Western medicine over the ‘superstition’ associated with Indigenous approaches to mental health, psychiatry imposes a Western view of illness and healing.” Consequently, in colonised countries around the world, people from Indigenous communities and marginalised groups are more likely to be subjected to coercive psychiatric practices that white individuals. And people who experience coercive psychiatric practices are also more likely to have problems with criminal justice and child welfare systems, suggesting such psychiatric techniques are focusing more on control and punishment than therapy.

In theory, everyone should be equal under the eyes of the law. However, in practice, law is commonly used as a tool for systemic marginalisation. “The legal field is largely monopolised by the elite,” explains Emmanuelle. Limited access to legal education means that most legal professionals come from wealthy backgrounds, leading to a rift between the experiences of legal practitioners and those of people caught up in legal systems. “Legal professionals do not understand the complexity of the social issues at play,” says Emmanuelle. “Additionally, people subject to legal orders are disproportionately poor, and become further impoverished due to legal decisions made against them.”

How can people working in psychiatry and law improve social justice?

The systemic inequalities in psychiatry and law may seem entrenched, but many people are working to make these systems more equitable for all. “Psychiatric and legal professionals must acknowledge the wisdom of the individuals they serve and recognise that communities have the knowledge to develop valid options for themselves,” says Emmanuelle. “It’s important that they ask themselves why the most educated and privileged members of society are the ones making the decisions that affect others, without considering their situations.”

Pathway from school to psychiatry and law

• If you are interested in psychiatry, it would be useful to study science, mathematics and psychology at school. You will then need to study a psychiatry medical degree at university. Check the requirements for the country you want to work in, as every healthcare system is different and requires different qualifications.

• If you are interested in law, it would be useful to study English, history and philosophy at school. You will then need to study a law degree at university. Check the requirements for the country you want to work in, as every legal system is different and requires different qualifications.

• If, like Emmanuelle and Eva, you want to study psychiatry and/or law as a researcher, rather work as a psychiatrist or lawyer, then you could study a degree in psychiatry, psychology, law, philosophy or political science.

Explore careers in psychiatry and law

• Psychiatrists are health professionals who diagnose and treat mental health conditions. They may work in hospitals, private clinics, schools or prisons. Learn more about psychiatry from the Canadian Psychiatric Association: www.cpa-apc.org

• To gain experience in psychiatry, look for work experience or internship opportunities at health centres or with mental health organisations.

• There are many career opportunities in law. For example, lawyers represent clients during legal proceedings, judges and magistrates oversee court cases, politicians create a nation’s laws, and law researchers investigate how legal systems influence society. Learn more about the legal profession from the Federation of Law Societies of Canada: www.flsc.ca

• “Engage in law-related activities while at school, such as mock court competitions and debates,” advises Emmanuelle. “Gain first-hand experience of ordinary legal issues by volunteering with organisations that assist marginalised individuals.”

Meet Emmanuelle

I’ve always loved books, and reading and writing are my passion. When I was younger, I wanted to be a writer, so I went to university to study literature but soon realised that literature studies weren’t for me.

I switched to studying law because I didn’t know what else to do. While I didn’t enjoy the technical aspects of law enough to pursue a career as a lawyer, I was captivated by my first experience of conducting fieldwork for law research. That was when I understood that I wanted to spend my career researching the sociology of law, in partnership with marginalised communities and individuals.

Through my work, I uncover the structural issues behind psychiatric and legal practices related to social inequalities. I want to understand how and why the legal mechanisms meant to protect the rights of the most vulnerable people can result in blatant violations of these rights. I aim to expose how legal systems are used to marginalise, impoverish and stigmatise individuals and communities who are already marginalised.

My research has led to changes in legal practices, the development of new rights information documents that are now available in courts, and the inclusion of social workers in community legal clinics, and it has been cited in legal decisions regarding mental health rights.

In my free time, I enjoy spending time with my family and friends. I love activities such as hiking, cooking, playing with my dogs, and, of course, reading.

Emmanuelle’s top tips

If you’re interested in social research, build connections with community organisations as it’s essential to consider the knowledge and concerns of community members when developing research projects. It is also important to engage with political debates and social movements, as well as building scientific knowledge.

Meet Eva

I have always been a curious person. I love learning and sharing what I learn with everyone, young and old. I particularly enjoy visiting kokoms (grandmothers) and mocoms (grandfathers) in my community.

When I was younger, I thought that ‘law’ was inaccessible and intimidating. However, I discovered that I needed an understanding of law to serve my community. The Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok are in the process of negotiating a territorial and self-governance treaty with the Canadian federal and provincial governments, and I became a researcher for the Commission on the Atikamekw Constitution. I was shocked to discover that the technical terms of a Western constitution had no resonance among the Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok, so I decided to study law so I could explain the terms of the future Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok treaty to my community.

My family taught me to always help vulnerable people, which is why I am passionate about improving access to justice for marginalised communities. For me, it is important to contribute to the well-being of everyone.

When I’m not working, I like spending time with my family and children. I enjoy a range of creative activities, such as beading, sewing and drawing. I also love reading, watching movies, travelling and visiting friends. I have many hobbies, so I’m never bored!

Eva’s top tips

Take time to know yourself, discover your ‘gifts’ and seek out the lessons that will allow you to flourish and contribute to the well-being of everyone. Be creative to stay connected to the teachings of our elders.

Do you have a question for Emmanuelle or Eva?

Write it in the comments box below and Emmanuelle or Eva will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

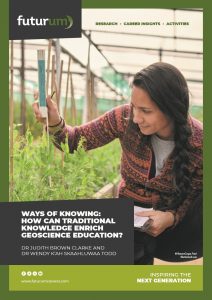

Emmanuelle and Eva are helping to incorporate Manawan traditional knowledge into mental health services. Learn how traditional knowledge can also enrich geoscience education:

0 Comments