How can people train their brains to manage depression?

TALK LIKE A NEUROPSYCHIATRIST

Amygdala — the region of the brain which is associated with processing emotional information

Biofeedback — a technique that teaches someone to control some of their body’s functions, such as their heart rate

Deep brain stimulation — a procedure which sends electrical impulses to specific areas of the brain

Electroconvulsive Therapy — a procedure conducted under general anaesthetic where a seizure is generated to cause chemical changes in the brain

Major depressive disorder — a psychiatric illness characterised by low mood and difficulty experiencing pleasure

Neurofeedback — a technique which teaches individuals how to control their brain functions

Non-invasive — a type of medical procedure that does not require inserting any instruments through the skin or into an opening of the body

Ketamine — a drug, originally used as an anaesthetic for animals and then people, now used to treat depression

Real-time — a type of process where feedback can be given as quickly as an action is occurring

Treatment resistant patient — someone who has failed to benefit from at least two antidepressant medications

Vagus nerve — a part of the body’s nervous system, playing a role in digestion and blood pressure, amongst other functions. Stimulating the vagus nerve with electrical signals stabilises the brain’s electrical activity

If for two weeks or more, a person has a continuous low mood, low self-esteem or loses interest in activities they would normally enjoy, they might have major depressive disorder (MDD). Some people might struggle with depression for a few weeks or months during a particularly hard phase of life, but some may struggle with it for years.

Social support, encouragement to change lifestyle patterns, therapy and antidepressant medication are initial treatments for people with MDD, but, unfortunately, these do not work for everyone. “Only half of patients who seek standard interventions will achieve sustained remission,” says Dr Kymberly Young, a neuropsychiatrist based at the University of Pittsburgh’s Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic. “The most common psychological therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy, is often not effective in severely ill patients.”

If these initial treatments do not work, patients might have treatment-resistant depression. They might then try invasive treatments such as electroconvulsive therapy, vagus nerve stimulation and deep brain stimulation, or be prescribed ketamine – all of which pose significant risks to patients. “While ketamine has shown novel and promising antidepressant effects, it can also cause hallucinations, high blood pressure and confusion,” says Kymberly. To devise a safer, effective, non-invasive treatment for MDD, Kymberly turned her attention to a region of the brain called the amygdala.

What is the amgydala?

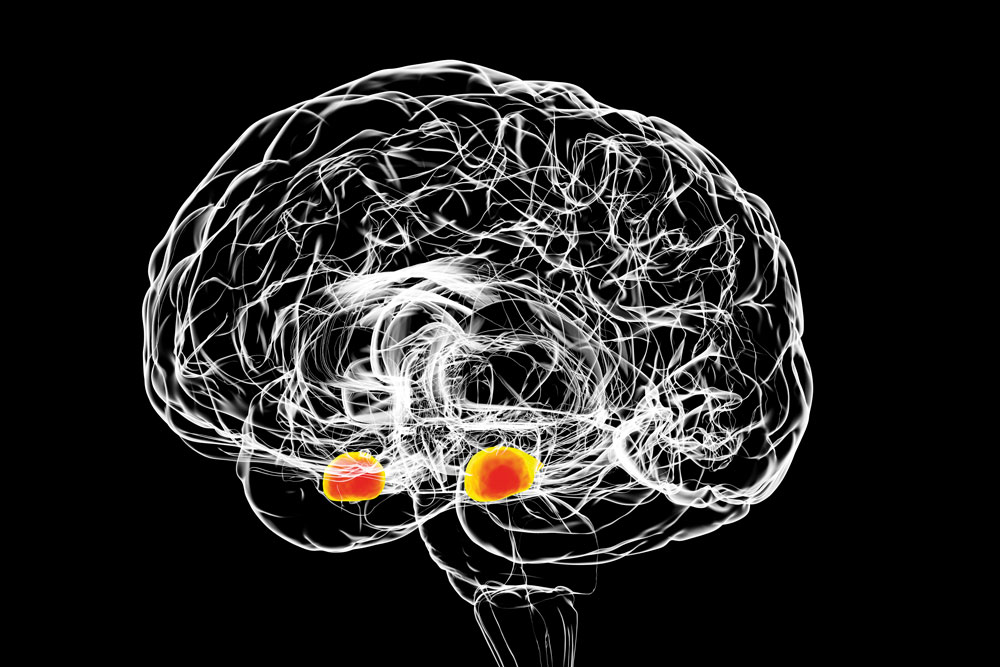

The amygdala is located deep within the middle of the brain. “Most people know that the amygdala is involved in the fight or flight response, but it does more than that,” says Kymberly. “The amygdala is a part of the brain that responds to important information – both positive and negative – and helps guide behaviour in response to this information.”

People with depression have an amygdala that is over-active to negative stimuli and under-reactive to positive stimuli, and, therefore, it acts differently to the amygdala of a healthy person. “For depressed patients, this means negative things stand out while positive things are not noticed,” explains Kymberly. Kymberly realised that lots of the treatment options currently available for MDD were aimed at controlling negative thoughts, but few tried to increase positive thoughts instead. “By targeting the amygdala, our goal is to make positive memories stand out more and be more useful to individuals.”

How can Kymberly do this?

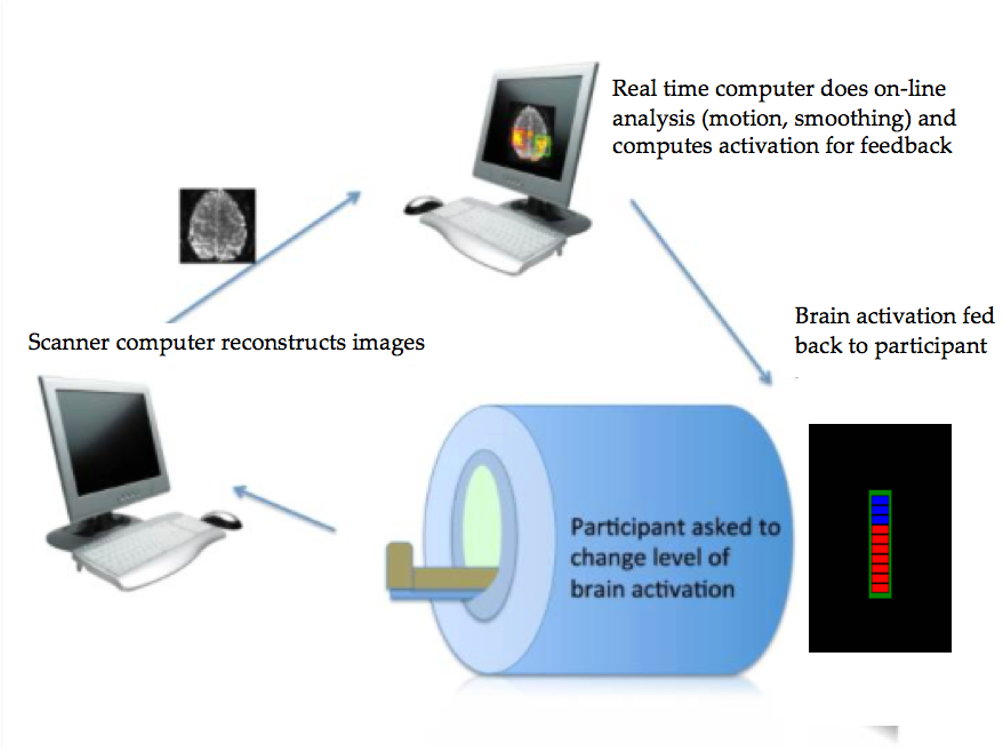

To see the activity of a specific area of the brain like the amygdala, Kymberly uses functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) neurofeedback. fMRI is based on the same technology as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) but there are crucial differences between the two. While MRI machines are scanning tools that produce images of the body and allow doctors to make sure everything is in the right place, an fMRI takes images of a brain’s activity while it is performing a specific function.

More specifically, Kymberly uses a technique called rtfMRI which stands for real-time functional MRI. “This is a technique that allows data to be processed as quickly as it is acquired,” says Kymberly. This means a patient getting rtfMRI can effectively ‘see’ their thoughts and witness the activity of their brain as it is happening.

How does an fMRI machine detect activity?

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM338

© LIGHTFIELD STUDIOS / stock.adobe.com

fMRI works by measuring tiny changes in oxygen levels in the blood (blood-oxygen) in an active part of the brain. “The more active a certain brain area is, the more blood-oxygen it uses. This is an indirect measure of neural activity,” says Kymberly.

Before her patients enter the fMRI scanner, Kymberly works with them to come up with a few positive memories they will need to think about while they are in the machine. Positive memories are often quite difficult for patients with MDD to come up with, especially as they might struggle with low self-esteem. For example, a depressed patient who has what should be a positive memory of their graduation day might still have a negative association with this memory if they felt they had not made the most of their education since.

Once her patients have decided upon a few positive memories, they enter the fMRI machine, and Kymberly asks them to recall these memories to themselves (they cannot speak while in the scanner as the images will be blurry). The fMRI machine measures the activity in the amygdala, which allows Kymberly and the patient to see what is happening in their brain when they are thinking about a positive emotion.

“By focusing on the important and particularly positive aspects of their memory, their amygdala response will increase,” explains Kymberly. This procedure lets patients know what it feels like when their amygdala is active and engaging with positive emotions, so that they can work on making this happen more often.

“Neurofeedback allows people to see how active certain parts of their brain are in real-time with the goal of teaching them to control it,” explains Kymberly. By presenting her patients with immediate feedback on their brain activity, they can be trained, over time, to learn to control that activity and increase their positive emotions.

Why is the fMRI machine necessary?

Using the fMRI machine to engage the amygdala of a patient is essential to Kymberly’s treatment. “Simply asking patients with depression to recall positive memories actually makes them more depressed,” says Kymberly. “For patients with MDD, their amygdala is not active when they engage with positive stimuli, and this may be one of the reasons they experience depression. We think the key is recalling positive memories while bringing the right brain regions online for the patients to see.”

What setbacks has Kymberly encountered?

One of the issues Kymberly has had to work against is negative feedback and disbelief from other scientists. “At my very first presentation of this research, someone came up to me and said, ‘Oh this is just Peter Pan. Think happy memories and you’ll fly.’”

However, Kymberly has stayed motivated and has even come to embrace this metaphor. “In Peter Pan, if you think happy thoughts and jump out the window, you will fall. It is only when you have been sprinkled with pixie dust that you are able to fly. As I said, if you just ask patients with depression to recall positive memories, they will feel worse. It is recalling positive memories while engaging the amygdala that allows people to benefit from their memories,” explains Kymberly. “Amygdala neurofeedback is the pixie dust for the brain.”

Where might this research go next?

Kymberly’s next steps are to conduct large scale clinical trials where she can compare neurofeedback to other available treatments such as antidepressants, psychotherapy and ketamine. “We want to show how well this intervention works relative to other treatments and determine which patients this might work best for,” she says.

DR KYMBERLY YOUNG

DR KYMBERLY YOUNG

Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, USA

Field of research: Neuropsychiatry

Research project: Developing rtfMRI neurofeedback for patients with major depressive disorder

Funder: National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)

This work was supported by the NIMH, under award number R61MH115927. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMH.

ABOUT NEUROPSYCHIATRY

According to the American Psychiatric Association, psychiatry is “the branch of medicine focused on the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of mental, emotional and behavioural disorders”. Approximately one in twenty adults in the world will struggle with depression in their lifetime, and one in five adults in the US will experience some form of mental disorder. As a result, choosing to work in psychiatry can allow you to make significant improvements to people’s lives, whether by helping deliver current treatments or by paving the way to new, ground-breaking techniques.

Neuropsychiatry is a sub-discipline of psychiatry that focuses on the role of the brain in the onset and recovery from psychiatric disorders.

Many people confuse psychiatrists with psychologists, but these are quite different professions. Psychiatrists are medical professionals who can prescribe medication and deliver a range of therapies for complex mental disorders, while psychologists provide psychotherapy (therapy based on talking) and do not have to be medical doctors.

What does Kymberly find rewarding about working in psychiatry?

“We are actually using what we’ve learned from decades of neuroimaging research into the causes of depression to develop a new treatment. My research has the potential to change people’s lives for the better, and that is incredibly rewarding.”

What research opportunities will be open to the next generation of psychiatrists?

“The field is moving towards more personalised treatment approaches,” says Kymberly. “Rather than a one-size-fits all approach to treatment, in the future we will look at the characteristics of individuals to determine what treatment will work best for them. This includes neural characteristics, or selecting a treatment based on how their individual brain functions.”

Pathway from school to neuropsychiatry

• To become a psychiatrist, you will need to study a degree in medicine before going on to do specialised training. In the US, this means you will do an additional four years of training in psychiatry after your medical degree.

• To work in any career in neuropsychiatry, Kymberly recommends gaining a solid background in both psychology and neuroscience. “Courses in statistics and computer programming are also very helpful,” she adds.

• Get involved with research as early as you can. “Use the connections your mentors and teachers have made to connect with individuals doing work that excites you. The Society for Biological Psychiatry is an excellent resource for those wishing to pursue a career in neuropsychiatry,” says Kymberly.

• The University of Pittsburgh offers numerous research training opportunities for undergraduate students. As well as this, the university’s Summer Premedical Academic Enrichment Program is open to underrepresented minority college undergraduates who want to pursue careers in medicine.

Explore careers in neuropsychiatry

• The American Psychiatric Association has information on choosing a career in psychiatry and what psychiatry involves.

• According to U.S. Bureau of Labour statistics, the average annual salary for a psychiatrist in the USA is $240,000. This is the highest mean wage of all mental health occupations.

• The National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH) has lots of resources and interesting articles about what is happening in the world of psychiatry.

Meet Kymberly

Who or what inspired you to become a scientist?

I went to college thinking I was going to be a lawyer. In my sophomore year, I took an elective called “The Pathological Brain”. I fell in love with neuroscience and never looked back. I had an amazing professor at Dickinson College named Dr Anthony Rauhut. He made the brain something interesting to study and easy to understand. Dr Rauhut was incredibly supportive. He helped me fine-tune my ideas into testable hypotheses and encouraged me to pursue what fascinated me about the brain. I would likely be a lawyer today if I hadn’t stumbled into his class!

In addition, my postdoctoral mentor Dr Jerzy Bodurka shaped me as a scientist. His dedication to pushing the limits of technology, and his warm and inclusive leadership style made me into the careful and compassionate scientist I am today.

What is the biggest factor that has helped you succeed?

Other people! You can’t succeed as a scientist working in isolation. There are so many things you have to be good at: neuroscience, psychology, computer programming, statistics, biology, electrophysiology, physics, creative thinking, writing and public speaking. You can’t do it all! Working with people who can help you in the areas you are weakest in enables you to build a strong and successful research programme.

What is the worst piece of advice you have been given?

To act more like a man and not show emotions! Not only was this extremely sexist advice (given by a man), it was also impractical and harmful. Allowing people to see you as a human who reacts to successes and failures, just like any other human, strengthens relationships and promotes good collaborations. When you don’t show any emotions, people become distant and afraid of you. I unlearned this advice by working with inspiring mentors who were open in showing their emotions and having honest reactions.

What are your proudest career achievements so far?

When I was a postdoctoral scientist, I was awarded the National Institutes of Health’s Pathway to Independence K99/R00 award. This is an incredibly difficult grant to get, and only the strongest applicants who the NIH believes will be successful at changing the world are awarded it. Getting my first randomised clinical trial of neurofeedback published in the American Journal of Psychiatry was also a very proud moment for me.

More recently, I served as the chair of the programme committee for the Real-time Functional Imaging and Neurofeedback (rtFIN) conference. I was so proud of how well that conference turned out – both in terms of scientific content and for the chance to interact with other leaders in the field.

What are your ambitions for the future?

I really want to make amygdala neurofeedback available as a treatment option for patients with depression. Translating scientific findings into clinical practice is challenging, but I am determined to work with doctors, patients, insurance companies and communities to make this a widely available intervention for patients with MDD.

Kymberly’s top tips

1. Be passionate. One thing I didn’t learn until I was a graduate student is that, in research, you fail more often than you succeed. When you get a paper or grant rejection, don’t give up. Being passionate about what you do is critical. If you aren’t invested in your work, it’s much harder to accept these rejections and try again.

2. Be persistent. Incorporate feedback from rejections to make your project stronger.

Write it in the comments box below and Kymberly will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)