How does empathy help us to understand others?

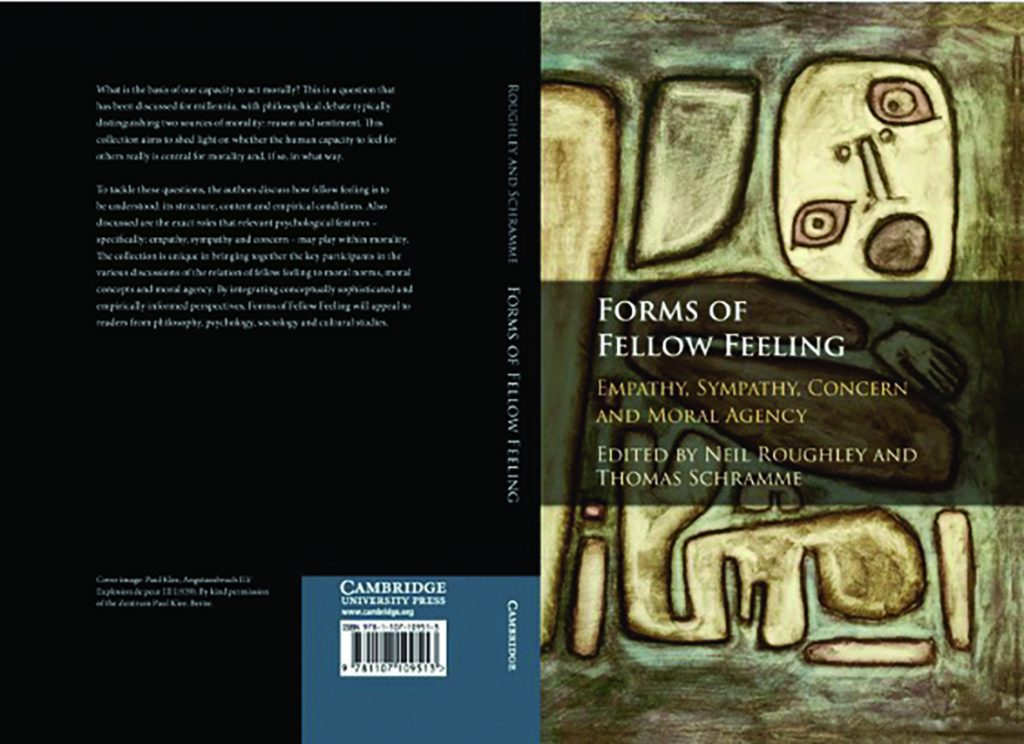

What does it mean to understand someone else? Some would say it requires knowledge of what that person is going through. Others would say shared personal experience is needed. One requirement for understanding is empathy, the skill of sharing another person’s perspective. At the University of Liverpool in the UK, Professor Thomas Schramme is investigating this connection between empathy and interpersonal understanding. With a team of researchers, he is developing a philosophical theory to explain the concepts behind interpersonal understanding, an ability that is increasingly important in today’s politically and culturally divided world

TALK LIKE A PHILOSOPHER

EMPATHY – the ability to share the perspectives and feelings of another being

INTERPERSONAL UNDERSTANDING – to gain appreciative knowledge of thoughts and feelings of others

SYMPATHY – the feeling of pity or sorrow for someone else

PHILOSOPHY – the study of foundational questions regarding all aspects of human and natural being, including knowledge, the mind, ethics and existence

DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY – the scientific study of how human thought and behaviour change over a lifetime

EMOTION REGULATION – the ability to manage and respond to our emotions

Many of us find it hard to understand the decisions that other people make. We may be concerned that our actions are not understood by others, we get frustrated when our friends and family cannot see something from our point-of-view, and we struggle to comprehend how someone could commit an atrocious act like murder. But why is it so hard to understand each other, and what prevents us from putting ourselves in someone else’s shoes?

Empathy is a skill that enables us to take the perspective of other beings and feel what they feel. Professor Thomas Schramme, a philosopher at the University of Liverpool, is using philosophical discussion and psychological findings to develop a theory relating empathy to interpersonal understanding. In a world that is becoming increasingly politically and culturally divided, this theory will aid future discussions by increasing our knowledge of how we understand each other.

EMPATHY AND INTERPERSONAL UNDERSTANDING

“Empathy is not itself a moral skill,” says Thomas, “but a mode of gaining understanding of another being.” For example, some con artists are very good at ‘getting into the heads of others’, and so are good at empathy, but they are not caring or moral, rather they use their skill in empathy to cheat others. Empathy is also often confused with sympathy, which is the feeling of sadness or pity you may feel if someone else is sad, whereas empathy involves a broader understanding of others.

Like any other skill, to be used successfully, empathy needs to be practised and developed over time. When used correctly, empathy provides a way to access the minds of others, helping us to understand their thoughts and actions, and enabling us to interact with them.

Although empathy plays an important role in connecting with others, more seems to be needed for full understanding. To some people, ‘understanding’ means knowing why someone else is feeling a certain way, while for others, it requires a shared personal experience. “For example, we struggle to empathise with people who commit hideous crimes,” explains Thomas. “In consequence, we can fail to understand them, even though we might know their motives.” Empathy and understanding, therefore, appear to be heavily linked, but full understanding likely requires more than just empathy.

HOW DOES THOMAS STUDY EMPATHY?

Thomas is a member of a research group investigating this connection between empathy and interpersonal understanding. Philosophers research a topic by checking reality (known as ‘phenomena’) against a specific concept. “We are concerned with conceptual problems and try to develop terminology related to these topics that is clear and unambiguous,” says Thomas. For example, Thomas may ask whether ‘emotional contagion’, such as our ability to pick up the mood of a room full of people, is really a form of empathy. “Does this phenomenon fall under the concept of empathy?”

Thomas is not only concerned with theoretical concepts. “We want to use findings from developmental psychology to reveal the reality of empathy,” he says. Hopefully, this will lead him to an empirically informed theory of empathy in relation to interpersonal understanding. “We want to explain how empathy works.”

THE LIMITS TO UNDERSTANDING OTHERS

In today’s world, it often seems like we are getting worse at understanding each other. Thomas believes that psychological mechanisms such as biases and poor emotion regulation are hindering our performance of empathy. And our increasing interaction through technology is not helping, as we lose so many social cues such as tone of voice and body language when we do not communicate face-to-face. When no personal connection exists, it is hard to ‘read’ someone, and so therefore harder to empathise with them.

We also struggle to grasp what understanding actually means, and what a successful version of empathy looks like. We often fail to understand what is good for others, meaning empathic decisions might not lead us to morally sound conclusions. And barriers to fully understanding someone are always going to exist. “It is a common feature of empathy that we cannot ever fully succeed in empathising, because we cannot ever be the other person,” says Thomas.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM185

EMPATHY – the ability to share the perspectives and feelings of another being

INTERPERSONAL UNDERSTANDING – to gain appreciative knowledge of thoughts and feelings of others

SYMPATHY – the feeling of pity or sorrow for someone else

PHILOSOPHY – the study of foundational questions regarding all aspects of human and natural being, including knowledge, the mind, ethics and existence

DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY – the scientific study of how human thought and behaviour change over a lifetime

EMOTION REGULATION – the ability to manage and respond to our emotions

Many of us find it hard to understand the decisions that other people make. We may be concerned that our actions are not understood by others, we get frustrated when our friends and family cannot see something from our point-of-view, and we struggle to comprehend how someone could commit an atrocious act like murder. But why is it so hard to understand each other, and what prevents us from putting ourselves in someone else’s shoes?

Empathy is a skill that enables us to take the perspective of other beings and feel what they feel. Professor Thomas Schramme, a philosopher at the University of Liverpool, is using philosophical discussion and psychological findings to develop a theory relating empathy to interpersonal understanding. In a world that is becoming increasingly politically and culturally divided, this theory will aid future discussions by increasing our knowledge of how we understand each other.

EMPATHY AND INTERPERSONAL UNDERSTANDING

“Empathy is not itself a moral skill,” says Thomas, “but a mode of gaining understanding of another being.” For example, some con artists are very good at ‘getting into the heads of others’, and so are good at empathy, but they are not caring or moral, rather they use their skill in empathy to cheat others. Empathy is also often confused with sympathy, which is the feeling of sadness or pity you may feel if someone else is sad, whereas empathy involves a broader understanding of others.

Like any other skill, to be used successfully, empathy needs to be practised and developed over time. When used correctly, empathy provides a way to access the minds of others, helping us to understand their thoughts and actions, and enabling us to interact with them.

Although empathy plays an important role in connecting with others, more seems to be needed for full understanding. To some people, ‘understanding’ means knowing why someone else is feeling a certain way, while for others, it requires a shared personal experience. “For example, we struggle to empathise with people who commit hideous crimes,” explains Thomas. “In consequence, we can fail to understand them, even though we might know their motives.” Empathy and understanding, therefore, appear to be heavily linked, but full understanding likely requires more than just empathy.

HOW DOES THOMAS STUDY EMPATHY?

Thomas is a member of a research group investigating this connection between empathy and interpersonal understanding. Philosophers research a topic by checking reality (known as ‘phenomena’) against a specific concept. “We are concerned with conceptual problems and try to develop terminology related to these topics that is clear and unambiguous,” says Thomas. For example, Thomas may ask whether ‘emotional contagion’, such as our ability to pick up the mood of a room full of people, is really a form of empathy. “Does this phenomenon fall under the concept of empathy?”

Thomas is not only concerned with theoretical concepts. “We want to use findings from developmental psychology to reveal the reality of empathy,” he says. Hopefully, this will lead him to an empirically informed theory of empathy in relation to interpersonal understanding. “We want to explain how empathy works.”

THE LIMITS TO UNDERSTANDING OTHERS

In today’s world, it often seems like we are getting worse at understanding each other. Thomas believes that psychological mechanisms such as biases and poor emotion regulation are hindering our performance of empathy. And our increasing interaction through technology is not helping, as we lose so many social cues such as tone of voice and body language when we do not communicate face-to-face. When no personal connection exists, it is hard to ‘read’ someone, and so therefore harder to empathise with them.

We also struggle to grasp what understanding actually means, and what a successful version of empathy looks like. We often fail to understand what is good for others, meaning empathic decisions might not lead us to morally sound conclusions. And barriers to fully understanding someone are always going to exist. “It is a common feature of empathy that we cannot ever fully succeed in empathising, because we cannot ever be the other person,” says Thomas.

A common topic in philosophical discussions of empathy is whether we can empathise with people who have completely different backgrounds to us. Some theorists argue that to understand someone requires shared knowledge or experience with them, however Thomas sees limitations in this argument. “We can at least partly overcome different backgrounds,” he says. “If we can accept there is always going to be a boundary to other minds, then cultural differences do not pose an insurmountable hurdle to successful understanding.” With this viewpoint, he highlights the importance of successful understanding, rather than full understanding, when interacting with others.

BECOMING A BETTER EMPATHISER

If empathy is a skill, how we can improve our success at using it? As Thomas suggests, our capacity to empathise is not fixed or limited by personal or social identities. “Empathic skill can be improved by self-knowledge and imagination,” he says. “If you know your weaknesses and biases, and can distance yourself from them, you have a good chance of improving your empathic abilities.” Thomas believes an important requirement for empathy is to focus on the other person and not on yourself. “When we empathise, another person is the target of our efforts,” he explains. “So we mustn’t ask ‘How would I feel in such a situation?’ but ‘How does this person feel?’”

Successful empathy is the ability to, as much as possible, understand the other person. And while it can be difficult to understand those with completely different life experiences, this is not a barrier to showing empathy. If we all developed our skills of empathy and used them to increase our interpersonal understanding, the world would likely be a much kinder and more compassionate place.

PROFESSOR THOMAS SCHRAMME

PROFESSOR THOMAS SCHRAMME

University of Liverpool, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Philosophy

RESEARCH PROJECT: Investigating the relationship between empathy and interpersonal understanding

FUNDER: Arts and Humanities Research Council

PROFESSOR THOMAS SCHRAMME

PROFESSOR THOMAS SCHRAMME

University of Liverpool, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Philosophy

RESEARCH PROJECT: Investigating the relationship between empathy and interpersonal understanding

FUNDER: Arts and Humanities Research Council

ABOUT PHILOSOPHY

Philosophy is the study of knowledge, the mind, ethics and our very existence. For thousands of years, we have been asking ourselves, ‘Why are we here?’ and ‘How do we even know that we exist in the way we perceive ourselves in the world?’ And today, philosophers are still trying to answer these questions.

Thomas specialises in moral and political philosophy, combined under the term ‘practical philosophy’ due to their concern with practices and actions. Humans behave in ways that have practical repercussions, for example someone’s actions may harm others, and moral and political philosophy involves asking questions about how we should behave.

Thomas is also interested in the philosophy of medicine. “Pretty much all traditional areas of philosophy can be applied to medicine,” he says. Ontology is the philosophical study of what exists and in what way. “This can be applied to the philosophical debate of whether mental disorders exist, or whether they are brain diseases,” explains Thomas. Epistemology, the study of knowledge, can be used to investigate how medical conditions are diagnosed. “Are patients’ illnesses diagnosed using certain rules and medical data?” asks Thomas. “Or do doctors use their intuition and experience to treat patients?”

WHAT ARE THE JOYS AND CHALLENGES OF BEING A PHILOSOPHER?

“I like the open nature of philosophy,” says Thomas. “There is no topic that might not become the object of philosophical thinking.” Thomas loves spending his working hours reading and thinking, allowing him to pursue his personal enjoyments as his job.

However, Thomas highlights this can also be a problem, as philosophy does not deliver products in a traditional way. “Philosophers don’t invent new technology or identify lifesaving treatments,” he says. This can lead some people to think that philosophy is a superfluous activity, nice if you have the time for it, but not a serious economical pursuit. Thomas thinks it’s important to fight this distorted image. “The benefits of philosophy are vast and they concern human thinking by offering new perspectives,” he says. “This does not have a monetary value but is invaluable nonetheless.”

WHAT IS THE FUTURE OF PHILOSOPHY?

Despite the challenges facing modern philosophers, Thomas thinks the field is an exciting one to work in. “You never know what philosophical issues will arise. That’s the beauty of it!” he says. “Suddenly, new ideas are introduced, and they change how we perceive the world.”

Philosophers address human issues, such as racism and climate change, and so they are vital for understanding how we can all live with each other and our planet. And new technological developments have philosophical implications. Modern philosophers ask questions about artificial intelligence and debate the concept of the ‘extended mind’. This view argues that our mental realm is not just inside our head but is extended to things in the world. With so much of our existence now dependent upon, and contained within, our phones, why are our phones not considered part of our mind? “Philosophy opens a completely new avenue of thinking and a new way of perceiving the world,” says Thomas.

EXPLORE A CAREER IN PHILOSOPHY

• The British Philosophical Association (www.bpa.ac.uk) contains resources for students (www.bpa.ac.uk/resources) and information for schools (www.bpa.ac.uk/philosophy-in-schools).

• The Royal Institute of Philosophy (www.royalinstitutephilosophy.org) organises public lectures and you can watch philosophers talk about philosophical issues through their YouTube channel (www.youtube.com/user/RoyIntPhilosophy).

• For an accessible introduction to philosophy, Thomas recommends Think, by Simon Blackburn, or any books by Julian Baggini.

• Visit the University of Liverpool’s Philosophy Department (www.liverpool.ac.uk/philosophy/outreach) to find out more about the subject.

• Be aware that there is a lot of bad (pseudo-) philosophy information on the internet. Thomas says that you may need experience to distinguish between it and true philosophical work.

• Reading and writing are essential skills for philosophers, and it is very useful if you enjoy them! Other necessary skills are the abilities to understand complicated debates, express your thoughts and form structured arguments.

• “Philosophers need the analytical skill of ‘logic’,” says Thomas. “They need to be able to unpick arguments by ascertaining whether a given conclusion logically follows the statements provided.”

• Many universities offer philosophy degrees. To become an academic philosopher like Thomas requires a lot of luck, so he advises against being single-minded about such a career path. But a degree in philosophy will teach you many skills of reasoning and logic, which will open doors to a wide range of careers outside academia.

HOW DID THOMAS BECOME A PHILOSOPHER?

WHAT WERE YOUR INTERESTS WHEN YOU WERE YOUNGER?

For a long time, I was far more interested in activities than thinking. I wanted to become a chef when I was a young teenager, then an industrial designer when I was a young adult. In high school, I started developing some interest in ethical topics and politics, but only decided very late to enrol for a philosophy degree.

WHAT INSPIRED YOU TO BECOME A PHILOSOPHER?

I never planned to become an academic. It was down to luck and partly caused by the fact that I was running out of options after finishing my PhD! Initially, I tried to get into writing for newspapers, but I didn’t have any contacts in journalism. Then, I got lucky and landed my first academic job in philosophy, which started my career.

HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE YOURSELF? ARE THESE USEFUL CHARACTERISTICS FOR A PHILOSOPHER?

I’d say I’m diligent and conscientious. I always try and give my best. This also makes me competitive, although I do support my colleagues and enjoy their achievements. I certainly believe these characteristics are helpful, but they are not required to become a successful philosopher.

WHAT IS YOUR FAVOURITE FACT ABOUT A FAMOUS PHILOSOPHER?

I have to say that most of them are quite boring people! For instance, Ludwig Wittgenstein, a famous philosopher who taught at Cambridge, is reported to have said that it did not matter to him what he ate, as long as it was the same every time. Apparently, he always ate the same meal! I don’t know if that’s really true, but I would say that indicates a character flaw, a kind of dietary narrowmindedness. Still, we don’t admire famous philosophers for their character, but for their thoughts.

WHAT DO YOU ENJOY DOING OUTSIDE OF WORK?

My main passion outside of work is football. I play for a vet’s team and try to squeeze in regular 5-a-side games with colleagues. I’m also interested in movies.

THOMAS’S TOP TIPS

01 Anyone can read philosophy and philosophise! Philosophy is a democratic pursuit.

02 See philosophy as an interpersonal activity. You don’t think alone, you are constantly in a conversation with others, even if they are not always present in person.

Do you have a question for Thomas?

Write it in the comments box below and Thomas will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

Hello Thomas,

I am one of those people who takes on the emotions of everyone in a room (emotional contagion). My daughters are all like this to varying degrees. My son has strong feelings around social justice issues (he’s a libra) but he does not have quite the same sensitivity to others emotions as my daughters and I do. I think that emotional contagion does indeed lead to an increased potential for empathy. The reason is because even when someone is against me and a conflict is brewing; I can sense their emotions and put myself in their shoes. I believe that emotional contagion limits my ability to de-humanize people even if I wanted to. I know that de-humanizing someone is the first step towards the potential for violence, whether it be in thought, word or deed. So, in such ways, I think emotional contagion builds empathy. Please share your thoughts on this with me? I think that empathy is a fascinating topic for a philosophical discussion.

Thanks Leslie, that’s a very interesting comment and an important question. Many empathy scholars try to make conceptual distinctions to better manage the often complex reality. In philosophical parlance, we accordingly speak of analytic distinctions. The distinction between emotional contagion and empathy is an example. It is usually said that in emotional contagion we don’t fully distinguish between ourselves and others. We “catch” an emotion but do not feel it in relation to someone else; as the other’s emotion. For empathy proper, some say, we need to be conscious of the other-oriented aspect of the feeling we have – that it originates from another person. Having said that, in reality it will often be very hard to actually diagnose such a difference between emotional contagion and empathy. Also, many scholars agree that they are closely related phenomena. So, in terms of your own and your children’s experience, you seem to have a high level of empathy, in the sense of a propensity or disposition. The performance of empathy, I’d say, still requires a lot of other elements; I don’t believe it is a fully automatic process. For instance, when you say that you sense angry emotions before a conflict breaks out, others might well “catch” that negative emotion and also get into an aggressive mood. You seem to be regulating this situation by adding imagination to the mix. So, I’d describe it as an additional empathetic element, which alters emotional contagion. It is an interesting question whether emotional contagion is hence something to overcome by more cognitive elements of empathy (imagining etc.) or whether, as you say, emotional contagion is actually a stepping stone in “humanising” others. I don’t have an answer to that question, but, in any event, it seems clear that the whole empathy “package” makes it harder for us to negate the “mindedness” (as it is usually put in the philosophical debate) of others. Through empathy (perhaps already through emotional contagion) we realise that others are minded creatures that can feel and can hence suffer harm. Perhaps this basic realisation is the foundation of morality and concerns for justice?

Thanks again Leslie.

Thomas