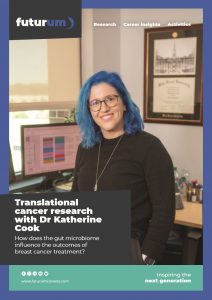

How does the gut microbiome influence the outcomes of breast cancer treatment?

There are trillions of microorganisms living in your gut. In addition to helping you digest food, your gut microbiome can impact how well you respond to medical treatments. At Wake Forest University School of Medicine in the US, Dr Katherine Cook is analysing faecal samples from breast cancer patients. She is exploring how the gut microbiome interacts with breast cancer therapies and whether simple dietary changes could improve treatment outcomes.

Talk like a translational cancer researcher

Gut microbiome — the combination of microorganisms (e.g., bacteria, viruses, fungi) that live in the gut and support digestion, immunity and overall health

Mediterranean diet — a diet high in healthy fats, such as olive oil and fish oil

Probiotic — a supplement (commonly found in yoghurt) containing live, beneficial microorganisms that support a healthy gut microbiome

Receptor — a structure on or inside a cell that attaches to specific molecules, such as hormones, and triggers a response in the cell

Translational research — a combination of lab-based and clinical research, with results from each informing the other

Western diet — a diet high in unhealthy saturated fats, sugar and salt

When Dr Katherine Cook was eight, her grandmother passed away from breast cancer. A few months later, Katherine’s aunt was also diagnosed with the disease. And since then, both Katherine and her mother have had surgery after discovering lumps in their breasts.

Katherine and her family are not alone. In most countries, breast cancer is the most common form of cancer in women. And in the US, 1 in 8 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer during their lifetime. “My own experience, coupled with my family history, has served as motivation for my career as a breast cancer researcher,” says Katherine. She conducts translational research at Wake Forest University School of Medicine to study how the gut microbiome interacts with breast cancer therapies.

What is the gut microbiome?

Your gut contains trillions of microscopic organisms, including bacteria, viruses and fungi. Together, they are known as the gut microbiome and play a vital role in keeping you healthy. “In a healthy person, these microorganisms live within us in a balanced state,” explains Katherine. “Your gut microbiome helps you digest the food you eat, generates vitamins to support your health, helps your immune system function, and protects you from infections.” Lifestyle factors, such as diet and medications, affect the health of your gut microbiome which, if it becomes unbalanced, can affect the health of the whole body.

How is the gut microbiome relevant to cancer research?

Some breast cancer patients are given oral medication that is absorbed into the body from the gut. This means the drugs will interact with the microorganisms in their gut, and Katherine wants to understand how this impacts the outcome of cancer treatment. Other patients are given immunotherapy – drugs that stimulate the immune system to kill cancer cells. “As the gut microbiome influences immune cell activity, it impacts immunotherapy efficacy,” explains Katherine. To explore these issues, Katherine is analysing faecal samples from breast cancer patients.

Why are faecal samples useful?

“Everybody poops!” says Katherine. “Faecal samples are non-invasive biospecimens that could help us determine whether a patient will respond to their therapies.” Patients in Katherine’s clinical trials collect faecal samples and send them to Katherine’s lab, where she analyses the DNA they contain. This allows her to determine what bacteria are present in the faeces and, therefore, in the gut microbiome. “We can then use this information to understand how the bacteria may be influencing the patient,” she explains.

How is Katherine conducting clinical trials?

In one trial, Katherine is researching hormone receptor-positive (HR+) breast cancer. This is the most common type of breast cancer, in which cancer cells have receptors that respond to oestrogen and progesterone. These hormones help the cancer to grow, so treatment involves drugs that reduce the hormones’ ability to send signals to the receptors.

Katherine is collecting faecal samples from patients before they start treatment and after one and three months of taking the drugs. “We will sequence DNA isolated from the samples and measure how the bacterial species change when HR+ breast cancer patients start therapy,” she says. “Some types of bacteria may affect how therapies are excreted from the body, which could change the drug bioavailability (the amount that enters the body).”

In another trial, Katherine is researching triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), a type of breast cancer that is more common in young and minority women. It requires a different type of treatment because the cancer cells lack hormone receptors, so patients are treated with a combination of chemotherapy (drugs that kill cancer cells) and immunotherapy.

Katherine is collecting faecal samples, blood samples and diet information from TNBC patients before and after they complete their treatment. “We aim to investigate if certain diets or gut microbiome species are associated with better health outcomes,” she says.

Why is translational research important?

In addition to her clinical trials, Katherine uses mouse models to test her clinical observations in the lab. “For example, if we identify bacteria that are enriched in the gut microbiome of breast cancer patients, we can feed these bacteria to mice with tumours,” she says. “This allows us to determine whether these bacteria may promote tumour growth or increase anti-cancer outcomes.”

Each discovery informs the next stage of Katherine’s work. By understanding how diet, the gut microbiome and cancer therapies interact, Katherine can design future clinical trials to test whether key dietary features could improve patients’ outcomes. “For example, if our clinical trial identifies that TNBC patients who eat at least 25 grams of fibre a day respond better to chemotherapy and immunotherapy, then we could design a study to determine whether fibre improves anti-cancer efficacy,” explains Katherine.

What has Katherine discovered?

Katherine’s clinical trials are still ongoing, but she has already made exciting discoveries from her lab-based research. She has shown that, if mice are fed an unhealthy Western diet, a probiotic made from the bacterium Lactobacillus improves the effectiveness of drugs to prevent HR+ breast cancer from recurring. “We have also demonstrated that mice with TNBC tumours respond better to immunotherapy if they are fed a Mediterranean diet rather than a Western diet,” she says. “In our clinical trial, we are now investigating whether women who eat more healthy fats respond better to immunotherapy.”

Katherine hopes her research findings will improve outcomes for future breast cancer patients. “Ultimately, I want our studies to improve clinical care to reduce breast cancer related deaths.”

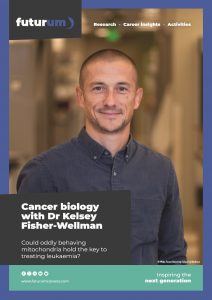

Dr Katherine Cook

Dr Katherine Cook

Associate Professor, Department of Cancer Biology, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, USA

Field of research: Translational breast cancer research

Research project: Analysing faecal samples to investigate how the gut microbiome interacts with breast cancer therapies

Funders: US National Cancer Institute (NCI); Department of Defense (DOD) Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program (CDMRP); metaVIVOR; The V Foundation

About translational cancer research

“Translational research bridges the gap between basic science and clinical practice to develop practical applications that will directly benefit patients,” says Katherine. Translational cancer researchers use lab-based methods and clinical trials to explore questions such as how cancer cells grow, how the immune system reacts and, in Katherine’s case, how the gut microbiome and diet might affect treatments. Answering these questions will lead to more effective prevention strategies and better therapies.

From bench to bedside and back again

“Translational research is defined as the ability to move scientific discoveries from the lab into the clinic for testing to develop real life applications,” says Katherine. This is often known as the ‘bench-to-bedside-to-bench approach’, where researchers make discoveries in the lab, then see if these apply in human testing, and then take the results of clinical trials back to the lab to build on them further.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM665

© Wake Forest University School of Medicine

This educational material has been produced by Wake Forest University School of Medicine in partnership with Futurum and with grant support from The Duke Endowment. The Duke Endowment is a private foundation that strengthens communities in North Carolina and South Carolina by nurturing children, promoting health, educating minds and enriching spirits.

Let us know what you think of this educational and career resource. To provide input, simply scan the QR code or click here.

For example, having discovered in the lab that mice with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) tumours respond better to immunotherapy when fed a Mediterranean diet, Katherine is now using her clinical trial to investigate whether women with TNBC who eat more healthy fats also respond better to immunotherapy. “This represents bench-to-bedside research,” she says. “But if we observe something different in the clinical trial, we would then go back to the lab to test that factor in mice, which would represent bedside-to-bench research.”

A day in the life of a cancer researcher

“Every day is different from the next!” says Katherine, whose tasks include collecting faecal and blood samples from the clinic then analysing them in the lab, meeting with students and collaborators to discuss research projects, and presenting scientific data at seminars. These different responsibilities enable Katherine to make advances in science, while improving the treatment outcomes for patients with breast cancer.

Pathway from school to translational cancer research

“Study anything and everything science!” advises Katherine. “It’s amazing how interconnected all the science topics are to each other. Chemistry and physic concepts relate to biological research questions. Studying chemistry could lead to the discovery of new cancer drugs, while studying physics could lead to the development of new diagnostic cancer techniques.”

As well as studying biology, chemistry and physics at high school, it would be useful to study mathematics to learn about statistics for analysing data, computing to learn coding for processing data, and psychology to help you relate to patients you work with during your career.

At university, a degree in biomedical science, biology or medicine could lead to a career in translational cancer research.

Look for opportunities to take part in scientific research to gain valuable work experience. “Participate in summer research experiences or volunteer at a science lab to find out what topics you are passionate about,” advises Katherine. “The Department of Cancer Biology at Wake Forest University School of Medicine (school.wakehealth.edu/departments/cancer-biology) has summer research programmes for high school and college undergraduate students.”

Explore careers in translational cancer research

“There are a lot of job opportunities for people with a PhD in biomedical sciences,” says Katherine. This includes roles in academia (conducting research at universities), industry (working for pharmaceutical companies) and government (working for organisations such as the National Cancer Institute [cancer.gov] or Food and Drug Administration [fda.gov]). “These paths can leverage your expertise and overall career interests.”

Explore organisations such as the American Association for Cancer Research (aacr.org), the American Institute for Cancer Research (aicr.org), the Cancer Research Institute (cancerresearch.org) and the American Cancer Society (cancer.org) to learn about recent cancer research and the type of careers available in the field.

Meet Katherine

I’ve always been interested in science, taking advance placement biology and chemistry coursework during high school. I also played soccer throughout high school and for a local team. My first job was a cashier at a grocery store. I hate to admit but to this day, I still remember those produce codes!

Breast cancer has profoundly impacted my family and served as a driver behind my desire to become a breast cancer researcher. My grandmother was diagnosed with the disease when I was young and, unfortunately, passed away. My mother and aunt have each had a double mastectomy (removal of both breasts). Then, when I was in graduate school in the middle of writing my PhD thesis, I found my own breast lump. I underwent surgery to remove the lump which, thankfully, was benign (not cancerous).

One of the most rewarding aspects of my job as a translational breast cancer researcher is seeing our laboratory-based discoveries move into the clinic. Working on clinical trial projects means participating in real-time to fulfil our ultimate goal of improving breast cancer patients’ outcomes and quality-of-life.

I started my research lab 10 years ago and in that time, I have experienced several momentous career achievements: my first graduate student obtaining her PhD degree, seminal lab discoveries on how diet influences breast tissue-resident microbiome populations, being awarded my first research grant, starting our first clinical trial at the Wake Forest Comprehensive Cancer Center. I have been proud of each of these moments.

I have the pleasure of working with brilliant students and colleagues who share the goal of reducing breast cancer risk and improving survivorship. My hopes for the future are to continue making meaningful advances in the field and to teach the next generation of cancer researchers.

In my free time, I run, work out and go to yoga class. Staying active helps clear my mind. I also enjoy travelling and experiencing new places.

Katherine’s top tips

1. Be curious and don’t be afraid of asking questions.

2. Don’t be discouraged when things don’t work out. Keep trying. Sometimes, the experiment that doesn’t work will be the most informative and will point you in a new direction.

Do you have a question for Katherine?

Write it in the comments box below and they will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

1 Comment

Submit a Comment

Discover how Katheine’s colleague in the Department of Cancer Biology at Wake Forest University School of Medicine is investigating blood cancer:

futurumcareers.com/cancer-biology-with-dr-kelsey-fisher-wellman

Hi, I’m currently a college student interested in having a career in cancer research and prevention, and in my class, we had to choose an article to research, and this one really stood out to me. I found your research super interesting, but I wanted to ask a quick question about whether the antibiotics used in cancer treatment would affect your research because I remember hearing that the antibiotics kill both the good and bad bacteria in your stomach, limiting the drug’s bioavailability. Thank you!