How texts from the past can shape and inform the future

Dr Alison Searle, based at the University of Leeds in the UK, is engaged in a project that analyses 17th century archival documents from three faith communities to address some of the contexts in which caregiving has emerged. The findings will highlight how historical practices of pastoral care and holistic well-being inform the present

GLOSSARY

ARCHIVAL – relating to an archive, a collection of historical documents

COLONIAL – relating to a colony, where settlers have taken control of/occupied another land

CATECHISE – instruct/teach Christian principles

MISSIONARY – a person sent to promote the Christian faith in a non-Christian country

NONCONFORMIST – a Christian of the Protestant Church who did not conform to the rule of the Church of England

PASTOR – a Christian minister or priest

PRESBYTERIAN – a type of Protestant Christian

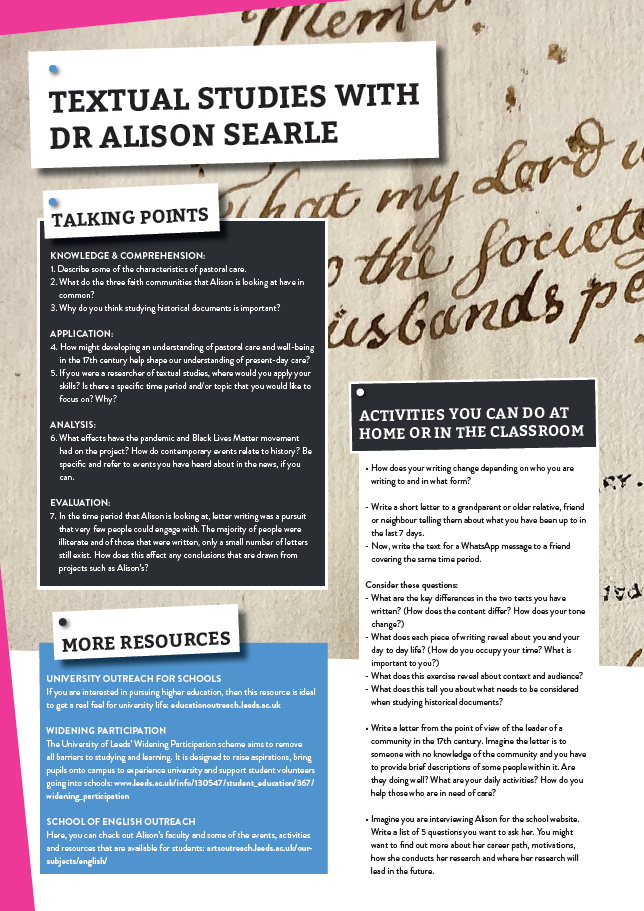

In an age where emails clutter up inboxes around the world and we conduct conversations using instant messaging apps, such as Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp, letter writing has decreased in popularity. However, this was not always the case – and let us be thankful for that, because the letter form can provide fascinating historical insights that shine a light on many aspects of life, society and the people who penned letters in bygone times.

Dr Alison Searle is an Associate Professor of Textual Studies at the University of Leeds in the UK who is acutely aware of the power of letters and other historical documents. One of the key things such texts reveal is context – by poring over archived materials, researchers gain a sense of how certain things were and how they may have shaped how things are now.

However, any textual studies come with a caveat – archival research is complex, in that it involves a history of suppression. We might ask whose documents get preserved, and who can access them? Are issues of survival and access simply about one’s personal identity, or part of a broader social world?

Alison is currently engaged in a project that is focused on the description and analysis of the concept of pastoral care within three faith communities that operated across the British Atlantic between 1630 and 1720. By analysing texts from this period, Alison hopes to understand how pre-modern care practices helped shape and inform those of today.

WHAT IS MEANT BY ‘PASTORAL CARE’?

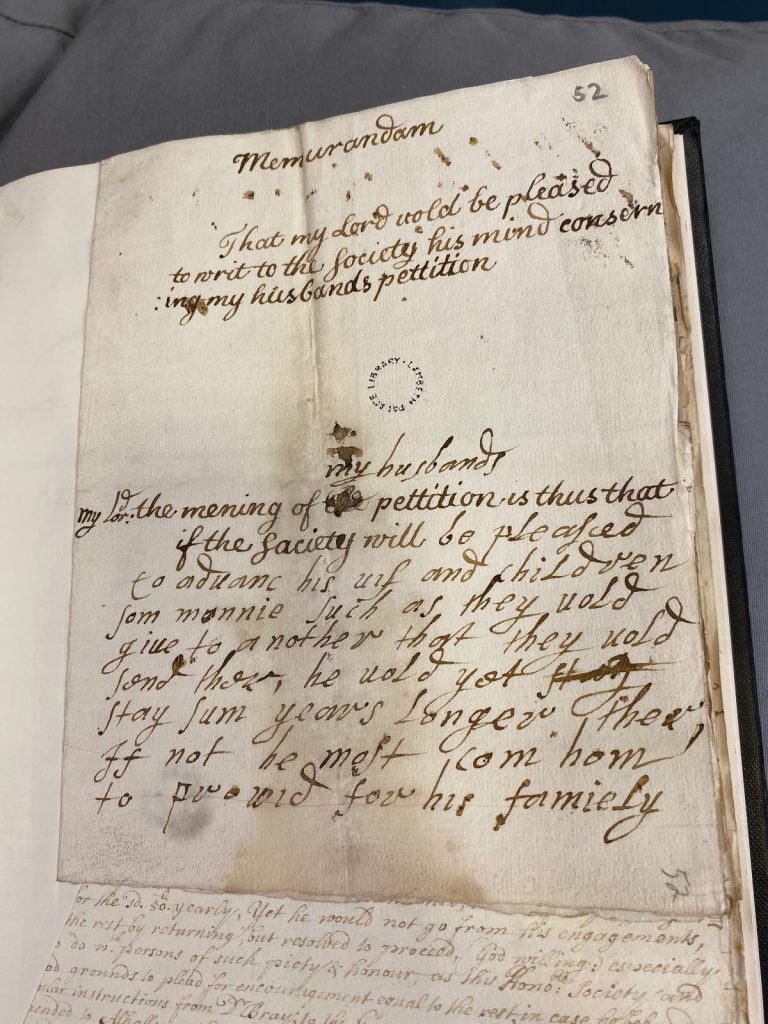

The focus of the project is on pastoral care in historical religious communities separated from one another, either due to oppression by the state, or because of new patterns of transatlantic travel resulting from commercial, colonial and missionary endeavours. In the context of the project, pastoral care describes attempts by these religious communities to provide for the well-being, health and flourishing of the souls, minds, and bodies of each of their members. Alison has partnered with a contemporary faith-based organisation called United Society Partners in the Gospel (USPG), which was founded in 1701, is still active today and forms an integral part of the project.

HOW HAS THE PANDEMIC HELPED CONTEXTUALISE THE RESEARCH PROJECT?

COVID-19 highlighted the importance of spiritual care as a critical component of public health provision. The significant increase in mortality in countries around the world helped bring local communities together and brought aspects of pastoral care into sharp focus, particularly how pastoral care is valued and how it is paid for. “Historically, (the forerunner of the USPG) The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel’s caregiving across the Atlantic was resourced by enslaved labour on plantations in the Caribbean. Legacies of enslavement involved an entanglement of (what some would have seen as) benevolence and violence in the provision of pastoral care that has implications for current thinking about mission, caregiving and global relationships,” explains Alison. “Communication and its importance to human connection and caregiving has become more obvious as a result of the pandemic – just as letters operated as a technology for remote caregiving and relationship building in the past, so Zoom/texts/phones suddenly became critical as a means of reaching out to others.”

As Alison highlights, communication and collaboration are also vital for her research. This project is seeing her work closely with the USPG’s research and learning advisor, Dr Jo Sadgrove, alongside postdoctoral researchers, archivists, digital editors and software engineers.

WHICH THREE FAITH COMMUNITIES IS THE TEAM FOCUSED ON?

The first is Scottish Covenanters, who were a group of radical nonconformists in 17th century Scotland. Samuel Rutherford was a presbyterian minister who was central to the Covenanters’ oppositional practices and his letters of pastoral care to women and men who were part of this godly resistance network have survived in printed form.

The second faith community of interest is English nonconformists. Richard Baxter was a leader of this group because of his reputation as a godly minister, his prolific writings (which number more than 130 books) and his important networks of influence. Baxter could not preach much after 1660, so he wrote books and letters instead – letters to and from men, women and young people from a wide range of backgrounds survive.

The final faith community is The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (the SPG, which has since evolved to become the USPG). It was founded in 1701, but it was focused outside of England – both to care for English nationals engaged in commerce in North America and the Caribbean, and to convert the indigenous peoples of the Americas and enslaved Africans. The letters that survive are an important record and archive of how the English state church tried to define its role beyond the borders of the nation state.

WHAT ROLE DID LETTERS PLAY WITHIN THESE COMMUNITIES?

It is important to consider the times and places in which these faith communities existed – after the British civil wars and Charles II’s restoration to the throne, many of the more radical religious groups in England (often known as puritans) were unable to continue to practice within the state church due to its coercive authority structures. Many had to move away – and this persecution and distance required each of these communities to develop forms of ministry and pastoral care that could be exercised through the genre of the letter. This meant that questions about how one should live, or deal with complex situations, or process grief, were explored in a dialogic exchange via letter (remote caregiving rather than face-to-face). In this context, letter writing takes on major importance as a means by which pastors provide care.

WHAT DO THE LETTERS REVEAL ABOUT THE ROLE OF THE PASTOR?

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM195

TALK LIKE A PALAEONTOLOGIST

COMPUTER TOMOGRAPHY (CT) – an imaging technique where multiple X-rays are taken of an object, then compiled to produce a 3D image of the object’s interior

ECOSYSTEM – all the organisms in an area, along with the non-living components

FOSSIL – the remains or traces of a prehistoric organism preserved in rock

OOPHAGY – an egg-eating behaviour exhibited by some animals

VERTEBRAE – the series of segmented skeletal supports running through the body axis and containing the spinal cord

VERTEBRATE – an animal that has vertebrae (e.g., fish, amphibians, reptiles and mammals)

It is no wonder that the legendary megalodon has captured our imaginations. Three times longer than a great white shark, this ferocious creature once terrorised the oceans. But today, all that remains of these ancient hunters are their teeth, preserved in stone for millions of years, and questions about their existence. Just how large could they grow? How big were their babies? How long did they live? And what role did they play in prehistoric ecosystems?

By studying fossils of ancient sharks and comparing these to their modern-day relatives, Professor Kenshu Shimada, a shark palaeontologist at DePaul University, is hoping to solve some of the mysteries surrounding megalodon and other extinct sharks.

LAMNIFORM SHARKS

Professor Shimada’s research focuses on a diverse group of sharks called lamniforms. Lamniform sharks include plankton-eaters such as the basking shark, as well as meat-eaters like the famous great white shark. “Although only 15 lamniform species live in today’s ocean, there are many extinct species in the fossil record, including the iconic megatooth shark, Otodus megalodon,” Professor Shimada explains.

“There is much more to learn about the biology of each species,” he says. “We still don’t know about the shape, growth and behaviour of many species, or the roles they played in their ecosystems.” The discovery of new fossils, as well as the development of new methods to extract information from these fossils, will help palaeontologists like Professor Shimada to broaden our knowledge of prehistoric sharks.

WHAT CAN SHARK TEETH TELL US?

Sharks are cartilaginous fish, with skeletons made from cartilage rather than bone. Only their teeth are well mineralised, made of calcium phosphate. This means when a shark dies and sinks to the ocean floor, its soft skeleton tends to decay quickly, leaving behind only its hard teeth.

“For this reason, most extinct sharks in the fossil record are represented by isolated teeth,” explains Professor Shimada. “Teeth are usually the only clues left for palaeontologists to decipher ancient shark biology.” While it is challenging to determine the structure and lifestyle of an entire species based solely on a few dental remains, these teeth do provide a huge amount of evidence about the life of prehistoric sharks.

The shape of teeth provides clues as to what the shark ate. For example, flat teeth belonged to sharks which crushed shellfish, sharks which ate small fish and squid had pointy needle-like teeth, and sharp triangular teeth belonged to sharks which hunted large prey.

Palaeontologists can examine the chemical elements within fossils. Professor Shimada works with geochemists to determine chemical components preserved in fossilised shark teeth, which can indicate the likely diet and body temperature of extinct shark species, as well as ancient oceanic conditions in which the shark lived.

And the size of the teeth gives an indication of the size of the shark. Professor Shimada has examined the relationship between tooth size and body length in modern sharks. He uses this information to calculate the size of extinct sharks based on the size of their fossilised teeth. “Besides studying prehistoric sharks, I also study their modern relatives,” he says. “Without understanding the anatomy of modern sharks, it is practically impossible to figure out the biology of extinct forms.”

WHAT HAS PROFESSOR SHIMADA DISCOVERED ABOUT MEGALODON?

Recently, Professor Shimada studied an exceptionally well-preserved specimen of a megalodon that was discovered in Belgium in the 1860s. Unusually, when this shark died 15 million years ago, about 150 of its cartilaginous vertebrae became fossilised, providing a unique opportunity for Professor Shimada to study more than just its teeth.

By comparing the relationship of vertebral size and body length in modern great white sharks, palaeontologists can estimate the length of extinct sharks from the size of their vertebrae. The vertebrae in this megalodon specimen measure up to 15 cm, indicating that this individual was about 9 m long.

Professor Shimada used a technique called computer tomography (CT) to peer inside the fossilised vertebrae, looking for hidden anatomical structures. “The CT images revealed that the vertebrae had 46 growth bands,” he says. Much like the way annual growth rings form in trees, a shark’s age can be determined by counting the growth rings in its vertebrae. “Therefore, this 9-metre-long megalodon died when it was 46 years old,” explains Professor Shimada.

But that is not all that Professor Shimada discovered. “By back-calculating its body length when each growth band formed, my study suggests that the shark’s size at birth was about two metres in length,” he says. “This result implies that megalodon possibly gave birth to the largest babies in the shark world!”

HOW DID MEGALODON BABIES GROW SO LARGE?

As megalodons were already larger than a human by the time they were born, this suggests they were well-fed before birth. The most likely explanation for this is that the embryonic sharks fed on unhatched eggs of their siblings in the womb, a behaviour known as oophagy. While this might sound sinister, all modern-day lamniform sharks are oophagous, and the practice provides many advantages for the individuals which survive to birth.

“This egg-eating behaviour means that only a few pups will survive and develop,” explains Professor Shimada, “but each can grow considerably large before it is born. New-born megalodons would have an advantage in the ocean as they would already be large predators at birth, so they would be less likely to get eaten by other predators.”

While Professor Shimada’s research is painting a picture of the lives of the ferocious megalodon, there is still so much to discover about the ancient oceans.

The letters reveal that the pastor’s caregiving role is both extensive and intensive. “They include dealing with cases of conscience, such as the responsibilities of a wife whose husband has contracted a sexually transmitted disease; the fate of a child dying at 17 weeks old; the challenges posed by melancholy, a combination of physical, mental, emotional and spiritual symptoms, which could lead to the real possibility of suicide; whether one should catechise an enslaved person for the sake of their eternal soul, despite the resistance of their master; and whether one could take communion kneeling,” explains Alison. “For SPG missionaries, there were questions about how to run their ministry in their new environment, including how people could be ordained, and dealing with issues such as potential bigamy.”

WHAT ARE THE LONG-TERM IMPACTS OF THE PROJECT?

Ultimately, any project that analyses historical documents provides a new perspective by looking at them through the lens of the present day. In this regard, the future will always make the past fascinating in different ways. Of course, there is the context of COVID-19, but the Black Lives Matter movement also foregrounds the importance of considering legacies of enslavement which was rife at the times these letters were written.

From a caregiving perspective (which is the chief focus of the project), being able to get a real sense of what constituted caregiving in the 17th century helps us think about what constitutes it now. “In a sense, the letters and exchanges from the early archive have fed into the discussion of how to provide care during the pandemic health crisis,” says Alison. “Conversations with scholars working on selecting, transcribing and digitising the source material (and more specifically the enhanced visibility of the sources through the production of open-access digital surrogates) enabled USPG to explore what care in a global crisis might mean for an organisation positioned in the UK with a duty of care to people all around the world.”

DR ALISON SEARLE

DR ALISON SEARLE

Associate Professor of Textual Studies, University of Leeds, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Textual Studies

RESEARCH PROJECT: Contributing to present-day thinking about well-being and caregiving by studying pastoral care in three faith communities between 1630 and 1720

FUNDER: Arts and Humanities Research Council (award number AH/T003197)

DR ALISON SEARLE

DR ALISON SEARLE

Associate Professor of Textual Studies, University of Leeds, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Textual Studies

RESEARCH PROJECT: Contributing to present-day thinking about well-being and caregiving by studying pastoral care in three faith communities between 1630 and 1720

FUNDER: Arts and Humanities Research Council (award number AH/T003197)

ABOUT TEXTUAL STUDIES

Because textual studies can involve the study and analysis of any written material from any period of history, it is difficult to summarise what you might be studying if you pursue a career in the field. Whether it is carefully turning the pages of a folio edition of William Shakespeare’s plays, analysing the manuscripts of some of Emily Brontë’s poems, poring over 17th-century letters from three faith communities, or more besides, the choice is yours.

Alison is unequivocal about the appeal of textual studies. “The opportunity to explore manuscripts written by a range of people and organisations from several centuries ago and to piece together the different kinds of stories they allow you to tell about the past, and how it intersects with the present, is intellectually challenging and rewarding,” says Alison. “Thinking about how best to contextualise documents such as letters and make them accessible for a variety of contemporary audiences in order to reflect on how these documents were created, preserved, curated and disseminated, and what this means for our understanding of history and the development of specific literary genres in the present…these are the rewards.”

The relationship between historical manuscripts stored in archives and how they relate to present-day concerns will be an issue for future scholars, especially when we consider how these texts will be re-presented in new forms, such as digitally. “I think the Black Lives Matter movement will have a long-term impact on the field. In the course of my own research project, the iconic and iconoclastic toppling of Edward Colston’s statue in Bristol has been a key moment,” explains Alison. “A reminder that the presence of these histories casts a monumental shadow in public and urban spaces in very obvious ways and that the past is relevant to and has an impact on the modern day.”

Alison also knows that her identity as a white, female, middle-class researcher offers her certain privileges as well as possible limitations. Does Alison have more or less access to texts than others? Will her reading of those texts be influenced by her own identity? Is this just a question of her ‘identity’ or does it also reflect the power structures of a broader social world? Textual studies of historical documents have a bearing on our present lives and perspectives, and poses many such fascinating questions.

EXPLORE A CAREER IN TEXTUAL STUDIES

• Alison recommends taking a look at The Society for the History of Authorship, Reading and Publishing, which contains lots of useful information on the study of book history.

• There is also Early Printed Books, Critical Race Conversations and the Early Modern Letters Online Exhibition, all of which should whet your appetite and give you an idea of some of what Alison and others in her field are involved with.

PATHWAY FROM SCHOOL TO TEXTUAL STUDIES

Alison says that there is no direct pathway to a career in textual studies – mainly because it is a broad term that embraces literary criticism, editing, and working with written texts in a variety of media forms. “An interest in the written word, different media forms (manuscripts, printed texts, digital technologies), interpretation, contextualisation and storytelling is central,” explains Alison. “Any subject or activity that encourages digital literacy, or promotes an attentiveness to and engagement with other voices and focus on detail will help.”

www.prospects.ac.uk/careers-advice/what-can-i-do-with-my-degree/english

HOW DID ALISON BECOME AN EXPERT IN TEXTUAL STUDIES?

WHAT WERE YOUR INTERESTS WHEN YOU WERE GROWING UP?

I loved reading, writing, travelling and walking – especially by Sydney’s beautiful harbour and beaches.

WHO OR WHAT INSPIRED YOU TO PURSUE TEXTUAL STUDIES?

I enjoyed English literature, ancient and modern history, and computing studies at school. I continued to pursue these interests in my BA (Hons) degree in English literature, and then in my PhD on the Bible and imagination. Two of my earliest jobs involved editing for an online literary reference work and working with handwritten letters from 17th-century England exploring Richard Baxter’s correspondence with women. These experiences taught me the importance of attention to detail, the significance of the material form of a text, and the fascinating ways in which literary texts from the Renaissance and contemporary digital technologies intersect to allow new ways of reading, writing, thinking, imagining and contextualising. I was hooked.

WHAT ATTRIBUTES HAVE MADE YOU SUCCESSFUL AS A RESEARCHER?

An irritating habit of asking question after question after question! A love of learning all I can about a particular piece of writing and its different contexts: how it was produced, how it was received and the ways in which it can be interpreted now. Doing a PhD can be a rather solitary process – it requires self-discipline and detailed commitment to becoming an expert on one particular topic within a discrete period of time (usually three years). However, the attributes that make one successful as a PhD student are not necessarily sufficient to make one successful in different kinds of research projects. In my current work, I am part of a team – the contributions of archivists, digital editors, other academic researchers, and learning partners in non-academic organisations are absolutely crucial to the success of the project. This means that a willingness to listen, to learn, to know my areas of expertise, and my areas of ignorance, are also essential to producing high-quality interdisciplinary research.

ARE YOU A KEEN LETTER WRITER YOURSELF?

I wrote letters to friends and family as a child and teenager. Now, it’s more death by email, but I’ve been encouraging my 10-year-old son to write to family in Australia (all of our extended family are on the other side of the world, so it’s a tangible way to stay in touch).

WHAT ARE YOUR PROUDEST CAREER ACHIEVEMENTS SO FAR?

Getting my PhD when I was 25 and being able to use the non-gendered professional title of doctor; publishing my first book, based on my PhD thesis, in 2008; and learning to work collaboratively with non-academic partners and heritage organisations in a way that brings my work on historical literary texts into direct dialogue and engagement with contemporary concerns of public health and legacies of enslavement.

ALISON’S TOP TIPS

01 Follow what interests you, even if it is difficult to see how doing so will immediately lead to employability or a career. Skills in critical reading, interpretation and telling stories are valuable in many work environments.

02 Be open to learning new skills and take any opportunities that come your way. It is important to work with people rather than in competition with them!

03 If you’re not visible, or someone else’s voice is missing, write yourself in or provide a platform for that person to tell their story.

Do you have a question for Alison?

Write it in the comments box below and Alison will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)