Looking to the light: assessing the path to species recovery

Assessing species’ risk of extinction is essential for effective conservation efforts. However, this assessment does not tell the whole story – to understand the broader ecological picture, it is also important to know how the species is doing compared to pre-human involvement. Dr Molly Grace of the University of Oxford, UK, is using a new tool, the IUCN green status of species, to assess this

TALK LIKE A CONSERVATION SCIENTIST

ECOLOGICAL FUNCTION – the role(s) of a species in an ecosystem. For instance, predators can control prey populations, trees can provide habitats for other species

INDIGENOUS RANGE – the area(s) where a species was found before human influence

IUCN – the International Union for Conservation of Nature is made up of government and civil society organisations and is the global authority on the status of species and the wider natural world

IUCN GREEN STATUS OF SPECIES – a new tool in development by the IUCN that assesses the recovery of species and the success of conservation measures taken for that species

IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES – a tool developed by the IUCN that measures the risk of any particular species going extinct

SPECIES RECOVERY – According to the Green Status, a species is Fully Recovered when it is present, viable, and ecologically functional throughout its indigenous range. Achieving this looks different for each species

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) assesses the natural world and advises on measures needed to safeguard it. Their ‘Red List of Threatened Species’ measures species’ risk of extinction and is used by governments and conservationists around the world to guide conservation action. However, the Red List does not tell the whole story.

Dr Molly Grace of the University of Oxford is the Task Force Co-Chair for the IUCN Green Status of Species. This new assessment tool focuses on evaluating species’ recovery rather than simply avoiding extinction, allowing conservationists to determine how well their efforts are working.

THE GRAY WHALE’S TALE

The charismatic gray whale, found in the Pacific Ocean, is a favourite with whale-watching tours along the west coast of the USA. The species’ changing fortunes in recent centuries paint a clear picture of why both the Red List and the Green Status are useful measures of a species’ well-being.

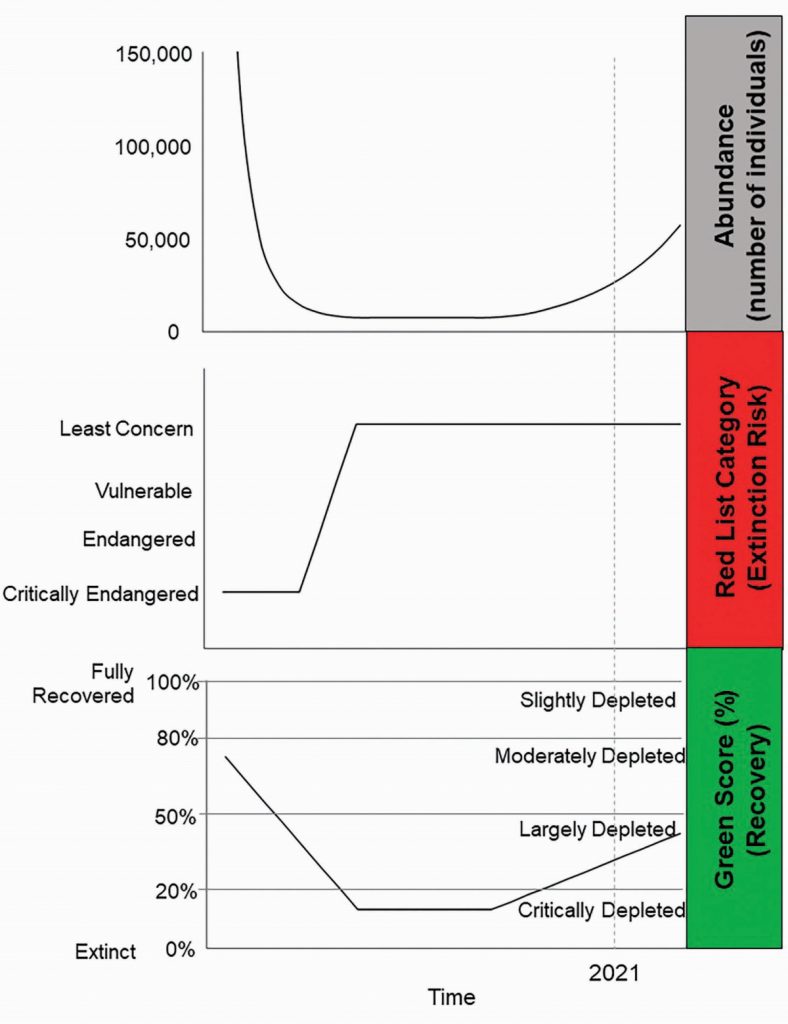

Before commercial whaling took off in the 1700s, there were >100,000 gray whales in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. Hunting dramatically reduced their numbers – the entire Atlantic population was eradicated and <10,000 individuals remained in the Pacific. Rate of change in population size is a principal metric for the Red List, so the plummeting gray whale population would have resulted in the species being classified as ‘Critically Endangered’ (if the Red List had been in use then) meaning it was likely to go extinct.

Mounting international concern meant commercial whaling was largely banned in 1949, after which gray whale populations began to stabilise. With a stable population, gray whales were classified as ‘Least Concern’ when the Red List was first implemented, the best classification possible, with no risk of extinction. Gray whale populations have even grown a little since then. “However, the current population size is still much, much smaller than before centuries of whaling,” says Molly. “Scientists might wonder – what is the ecological impact of removing all these whales from the ecosystem?”

This is where the Green Status comes in. By this assessment, gray whales were ‘Critically Depleted’ after whaling ended. Recent increases in their population means they have been upgraded to ‘Largely Depleted’ as their numbers are still significantly lower than in pre-whaling days, despite their Red List classification of ‘Least Concern’. This shows that conservation efforts have been successful, but there is still a long way to go. In fact, the effects of fishing, shipping and loss of sea ice may mean that populations can never return to pre-whaling levels.

ASSIGNING THE GREEN STATUS

“Extinction risk is measured in absolute numbers (if population size has dropped below a certain threshold, or if decline is happening at a certain rate) but recovery is relative,” says Molly. “Assessment of recovery uses several factors:

- Where the species was found prior to major human impacts;

- How much of that historical range the species currently occupies;

- The likelihood of the species continuing to exist in those areas (its viability);

- Whether the species is performing its ecological functions.

Once we have these measurements, a species is assigned a category, ranging from Fully Recovered to Critically Depleted.”

However, assessing these criteria is not simple, as population declines often began before scientists were recording population sizes. Techniques such as examining genetic diversity in existing populations can be used to estimate past conditions. “Where a species was found at the date when humans began to influence its numbers or distribution is known as its ‘indigenous range’,” says Molly. “If we don’t know when exactly that is, we estimate for 1750, the start of the industrial revolution.”

Scientists divide this indigenous range into spatial units (representing natural divisions within the species, such as subspecies or geographically separate areas of the indigenous range) and assess how the species is doing in each. Often, there are spatial units where the species is now absent, such as the gray whale being extinct in the Atlantic Ocean. “In each spatial unit, we identify whether the species is currently absent, present, viable (not at risk of extinction), or ecologically functional,” explains Molly. “This information is converted into a Green Score. If the species is ecologically functional in all spatial units, the score is 100% and the species if Fully Recovered. If the species is absent in all spatial units, the score is 0% and the species is Extinct (or Extinct in the Wild).”

Scientists also consider the effect that conservation actions have had on a species. “We can estimate what the Green Score would be if no conservation had been done, which can indicate that things would be worse with no conservation efforts,” says Molly.

FINE-TUNING THE GREEN STATUS

To ensure the Green Status provides useful information about species recovery, workshops were run for scientists to discuss how to measure and define ‘recovery’, before testing this on real species. “I worked with over 200 conservation scientists in 38 countries to apply our work to the species they were studying, and improved our methods using their feedback,” says Molly.

Creating a tool that captures complexity but is still usable is no easy task. “One big challenge has been designing the Green Status method to be scientifically rigorous but also user-friendly,” says Molly. “It’s a compromise between making it reflect reality as closely as possible, and actually being understandable!”

GOOD NEWS AND NEXT STEPS

“So far, we’ve tested 123 threatened species from the Red List,” says Molly. “Of those, we estimate that 33 of them (including the California condor, Jamaican rock iguana, and Chinese swamp cypress) would be extinct today if it wasn’t for the hard work and successful actions of conservationists.”

Next, Molly aims to capture enough Green Status assessments to understand global patterns of species recovery, helping scientists to plan future conservation efforts. While the Red List helps conservationists prioritise which species most urgently need conserving, the Green Status points to a brighter future – recovery of species, and ultimately entire ecosystems.

DR MOLLY GRACE

DR MOLLY GRACE

Task Force Co-Chair for the IUCN Green Status of Species, Department of Zoology and Wadham College, University of Oxford, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH : Conservation, Ecology

RESEARCH PROJECT : Coordinating the development of the IUCN Green Status of Species, to assess species’ progress towards recovery.

FUNDERS: Natural Environment Research Council, re:wild, IUCN Species Survival Commission, University of Oxford This work is supported by NERC (NE/S006125/1). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NERC or UKRI.

ABOUT CONSERVATION

Conservation is the study of biodiversity loss, and how this loss can be prevented or reversed. Conservation can encompass a broad range of careers; while some conservationists work on the frontlines, collecting species data in the field or engaging governments and communities in conserving biodiversity, others may perform lab experiments or build computer models. Molly’s role involves bringing together conservationists around the world to build and test the structure of the IUCN Green Status of Species. She explains more about her career.

WHAT DO YOU FIND MOST REWARDING ABOUT YOUR ROLE?

I really enjoy the opportunity to learn something new every day. Working on the Green Status means that I often dig deep into the histories of species that I sometimes didn’t even know existed!

ARE YOU OPTIMISTIC ABOUT THE FUTURE OF CONSERVATION?

I am optimistic, because there is lots of evidence that shows that conservation works to prevent extinction and aid recovery. Over the next few years, I expect that Green Status assessments will provide lots more evidence. While observing declines in nature can be bleak, there is a growing movement called Conservation Optimism which champions conservation success stories.

WHAT ISSUES WILL THE NEXT GENERATION OF CONSERVATIONISTS FACE?

Today, we know that successful conservation must include human needs. ‘Old-school’ conservation efforts sometimes involved forcibly removing indigenous people from their homes when protected areas were established. Today, community-based conservation efforts that are inclusive and collaborative are far more sustainable and ethical for both people and nature.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM152

ECOLOGICAL FUNCTION – the role(s) of a species in an ecosystem. For instance, predators can control prey populations, trees can provide habitats for other species

INDIGENOUS RANGE – the area(s) where a species was found before human influence

IUCN – the International Union for Conservation of Nature is made up of government and civil society organisations and is the global authority on the status of species and the wider natural world

IUCN GREEN STATUS OF SPECIES – a new tool in development by the IUCN that assesses the recovery of species and the success of conservation measures taken for that species

IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES – a tool developed by the IUCN that measures the risk of any particular species going extinct

SPECIES RECOVERY – According to the Green Status, a species is Fully Recovered when it is present, viable, and ecologically functional throughout its indigenous range. Achieving this looks different for each species

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) assesses the natural world and advises on measures needed to safeguard it. Their ‘Red List of Threatened Species’ measures species’ risk of extinction and is used by governments and conservationists around the world to guide conservation action. However, the Red List does not tell the whole story.

Dr Molly Grace of the University of Oxford is the Task Force Co-Chair for the IUCN Green Status of Species. This new assessment tool focuses on evaluating species’ recovery rather than simply avoiding extinction, allowing conservationists to determine how well their efforts are working.

THE GRAY WHALE’S TALE

The charismatic gray whale, found in the Pacific Ocean, is a favourite with whale-watching tours along the west coast of the USA. The species’ changing fortunes in recent centuries paint a clear picture of why both the Red List and the Green Status are useful measures of a species’ well-being.

Before commercial whaling took off in the 1700s, there were >100,000 gray whales in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. Hunting dramatically reduced their numbers – the entire Atlantic population was eradicated and <10,000 individuals remained in the Pacific. Rate of change in population size is a principal metric for the Red List, so the plummeting gray whale population would have resulted in the species being classified as ‘Critically Endangered’ (if the Red List had been in use then) meaning it was likely to go extinct.

Mounting international concern meant commercial whaling was largely banned in 1949, after which gray whale populations began to stabilise. With a stable population, gray whales were classified as ‘Least Concern’ when the Red List was first implemented, the best classification possible, with no risk of extinction. Gray whale populations have even grown a little since then. “However, the current population size is still much, much smaller than before centuries of whaling,” says Molly. “Scientists might wonder – what is the ecological impact of removing all these whales from the ecosystem?”

This is where the Green Status comes in. By this assessment, gray whales were ‘Critically Depleted’ after whaling ended. Recent increases in their population means they have been upgraded to ‘Largely Depleted’ as their numbers are still significantly lower than in pre-whaling days, despite their Red List classification of ‘Least Concern’. This shows that conservation efforts have been successful, but there is still a long way to go. In fact, the effects of fishing, shipping and loss of sea ice may mean that populations can never return to pre-whaling levels.

ASSIGNING THE GREEN STATUS

“Extinction risk is measured in absolute numbers (if population size has dropped below a certain threshold, or if decline is happening at a certain rate) but recovery is relative,” says Molly. “Assessment of recovery uses several factors: – Where the species was found prior to major human impacts;

- How much of that historical range the species currently occupies;

- The likelihood of the species continuing to exist in those areas (its viability);

- Whether the species is performing its ecological functions.

Once we have these measurements, a species is assigned a category, ranging from Fully Recovered to Critically Depleted.”

However, assessing these criteria is not simple, as population declines often began before scientists were recording population sizes. Techniques such as examining genetic diversity in existing populations can be used to estimate past conditions. “Where a species was found at the date when humans began to influence its numbers or distribution is known as its ‘indigenous range’,” says Molly. “If we don’t know when exactly that is, we estimate for 1750, the start of the industrial revolution.”

Scientists divide this indigenous range into spatial units (representing natural divisions within the species, such as subspecies or geographically separate areas of the indigenous range) and assess how the species is doing in each. Often, there are spatial units where the species is now absent, such as the gray whale being extinct in the Atlantic Ocean. “In each spatial unit, we identify whether the species is currently absent, present, viable (not at risk of extinction), or ecologically functional,” explains Molly. “This information is converted into a Green Score. If the species is ecologically functional in all spatial units, the score is 100% and the species if Fully Recovered. If the species is absent in all spatial units, the score is 0% and the species is Extinct (or Extinct in the Wild).”

Scientists also consider the effect that conservation actions have had on a species. “We can estimate what the Green Score would be if no conservation had been done, which can indicate that things would be worse with no conservation efforts.” says Molly.

FINE-TUNING THE GREEN STATUS

To ensure the Green Status provides useful information about species recovery, workshops were run for scientists to discuss how to measure and define ‘recovery’, before testing this on real species. “I worked with over 200 conservation scientists in 38 countries to apply our work to the species they were studying, and improved our methods using their feedback,” says Molly.

Creating a tool that captures complexity but is still usable is no easy task. “One big challenge has been designing the Green Status method to be scientifically rigorous but also user-friendly,” says Molly. “It’s a compromise between making it reflect reality as closely as possible, and actually being understandable!”

GOOD NEWS AND NEXT STEPS

“So far, we’ve tested 123 threatened species from the Red List,” says Molly. “Of those, we estimate that 33 of them (including the California condor, Jamaican rock iguana, and Chinese swamp cypress) would be extinct today if it wasn’t for the hard work and successful actions of conservationists.”

Next, Molly aims to capture enough Green Status assessments to understand global patterns of species recovery, helping scientists to plan future conservation efforts. While the Red List helps conservationists prioritise which species most urgently need conserving, the Green Status points to a brighter future – recovery of species, and ultimately entire ecosystems.

DR MOLLY GRACE

DR MOLLY GRACE

Task Force Co-Chair for the IUCN Green Status of Species, Department of Zoology and Wadham College, University of Oxford, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH : Conservation, Ecology

RESEARCH PROJECT : Coordinating the development of the IUCN Green Status of Species, to assess species’ progress towards recovery.

FUNDERS: Natural Environment Research Council, re:wild, IUCN Species Survival Commission, University of Oxford This work is supported by NERC (NE/S006125/1). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NERC or UKRI.

ABOUT CONSERVATION

Conservation is the study of biodiversity loss, and how this loss can be prevented or reversed. Conservation can encompass a broad range of careers; while some conservationists work on the frontlines, collecting species data in the field or engaging governments and communities in conserving biodiversity, others may perform lab experiments or build computer models. Molly’s role involves bringing together conservationists around the world to build and test the structure of the IUCN Green Status of Species. She explains more about her career.

WHAT DO YOU FIND MOST REWARDING ABOUT YOUR ROLE?

I really enjoy the opportunity to learn something new every day. Working on the Green Status means that I often dig deep into the histories of species that I sometimes didn’t even know existed!

ARE YOU OPTIMISTIC ABOUT THE FUTURE OF CONSERVATION?

I am optimistic, because there is lots of evidence that shows that conservation works to prevent extinction and aid recovery. Over the next few years, I expect that Green Status assessments will provide lots more evidence. While observing declines in nature can be bleak, there is a growing movement called Conservation Optimism which champions conservation success stories.

WHAT ISSUES WILL THE NEXT GENERATION OF CONSERVATIONISTS FACE?

Today, we know that successful conservation must include human needs. ‘Old-school’ conservation efforts sometimes involved forcibly removing indigenous people from their homes when protected areas were established. Today, community-based conservation efforts that are inclusive and collaborative are far more sustainable and ethical for both people and nature.

EXPLORE A CAREER IN CONSERVATION

• Practical experience is highly desirable for a career in conservation. Molly emphasises this does not have to be in exotic locations; in the UK, work experience with local nature reserves or organisations such as the RSPB or Wildlife Trusts can be both educational and inspirational.

• Molly recommends the Conservation Careers website for seeking internships in the UK and further afield: www.conservation-careers.com/conservation-jobs

• The University of Oxford, where Molly works, offers a summer programme for A2 Biology students called the UNIQ Biology course, which gives an insight into the life of an undergraduate biologist at Oxford: www.uniq.ox.ac.uk/c/biology

• According to Talent.com, the average salary for a conservation scientist in the UK is around £31k.

Unlike research-focused sciences, a career in conservation can often involve the application of research findings as well as research itself. With this in mind, a broader skillset can be useful, though the sciences – especially biology – can provide a core grounding. Maths and statistics are often necessary skills for conservation research. Molly also recommends an understanding of psychology, social science, and history, useful for interpreting people’s interactions with nature. At university, degrees or modules in biology, ecology, and environmental science provide a clear path to a career in conservation.

HOW DID MOLLY BECOME A CONSERVATION SCIENTIST?

WHAT WERE YOUR INTERESTS WHEN YOU WERE YOUNGER?

My interest in conservation runs deep. When I was 10, I once spent most of a day performing a conservation translocation of hundreds of tadpoles, as the puddle they lived in was drying out in the summer sun! I have also always had a passion for musical theatre.

WHAT INSPIRED YOU TO BECOME A CONSERVATION SCIENTIST?

When I was an undergraduate, I got a job in a bird cognition lab. I started by cleaning cages, but over the years I got more involved with the lab’s research and eventually designed my own study, which became my first published academic paper. I realised I enjoyed the scientific process – having a question, and then performing experiments to find the answer. It’s very satisfying!

WHAT ATTRIBUTES HAVE MADE YOU A SUCCESSFUL SCIENTIST?

For me, the ability to communicate well is extremely important. Every scientist needs to apply for funding for their research, so you need to be able to get different audiences to understand why your work is interesting and important.

WHAT HAS BEEN YOUR PROUDEST CAREER ACHIEVEMENT SO FAR?

I have just had a paper accepted showing the results for the first batch of Green Status assessments. This paper has 203 authors from all over the world – most scientific papers have less than ten! Leading and co-ordinating that paper was a massive achievement for me, and I’m really proud to share our results with the world.

Often, scientists will spend at least the first decade of their career moving from one institution to another. This can be really fun and exciting, but also requires flexibility and bravery!

Do you have a question for Molly?

Write it in the comments box below and Molly will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)