The art of propaganda

Art and design have often had a major role in influencing the attitudes of society. Dr Harriet Atkinson, from the University of Brighton in the UK, is uncovering the role of modernist artists between 1933 and 1953 in Britain – how the influences of refugees, the outbreak of World War II and eventual victory all affected exhibitions, and how these in turn affected the people who saw them

GLOSSARY

COMMUNISM – an ideology where property is publicly owned and common ownership removes class divides

FASCISM – a far-right ideology based on an authoritarian leader and the power of the state

LEFT-WING – believing in social equality and egalitarianism

MINISTRY OF INFORMATION – a British government department responsible for public information and propaganda (active during the world wars)

MODERNISM – a period from the early to the mid-20th century when art and design left behind their classical routes and became more experimental

NAZI GERMANY – Germany between 1933 and 1945, under the control of the Nazi party, which was defined by dictatorship and persecution of minorities, and was defeated during World War II

PICTOGRAM – a graphic symbol or picture used to represent a message, idea or information

PHOTOMONTAGE – a photographic image made of several different photographs edited or pieced together

PROPAGANDA – materials designed to promote a particular political perspective

RIGHT-WING – having conservative or capitalist views and believing in free enterprise and private ownership

SOVIET UNION – a socialist state that existed from 1922 to 1991, which at its height encompassed Russia and many other countries in eastern Europe and central Asia. It was defined by communist ideals such as centralised command, but also by suppression and corruption

WORLD WAR II – the global war from 1939 to 1945 between the Allies (such as Britain, the Soviet Union and the United States) and the Axis powers (such as Germany, Italy and Japan)

When was the last time you saw an image – maybe an Instagram post or a meme shared in a WhatsApp group – that portrayed a strong opinion? In our modern age of digital communication, chances are very recently! Now, think about the last time you saw an image that portrayed a strong political opinion or idea. What message was it conveying? Was it persuasive? Did you agree with the message? Did you trust the message and share it with others? Did you question whether the image – and the message it was conveying – was accurate or ‘fake’? It is easy for us to link the concept of propaganda to the era of world wars, but it could be said that social media has made us all more politically active and, with the rise of misinformation, the use of propaganda more commonplace.

Dr Harriet Atkinson, Senior Lecturer at the University of Brighton in the UK, is a historian of art and design currently writing a history of political propaganda exhibitions that took place in Britain in the 1930s and 1940s. “For a long time, I’ve been interested in how governments use design to influence ideas about the nation, to persuade people of their point of view and to connect across national boundaries,” says Harriet. The exhibitions she is looking at were aimed to provoke a particular response, such as national pride or anti-fascist feeling – not so different from some of the images we see today.

“This particular area of British Modernism has been overlooked until now – possibly because it bridges several different disciplines, and the evidence for the exhibitions is hard to come by,” says Harriet. These exhibitions tended to be short-lived and records of their existence can be scant and scattered. Moreover, researching their impact on society involves piecing together many seemingly unrelated pieces of evidence. Harriet spends her days poring over archive material to build the picture of how these exhibitions arose and what they represented.

A TIME OF WAR

When World War II broke out, the British government’s Ministry of Information used exhibitions as a tool for generating particular emotions in the British public. “These exhibitions were designed to inspire audiences to live more efficiently, to take pride in the war effort, and to provoke anger against their enemies,” says Harriet. The rise in photography meant that images of real people and situations could be incorporated into propaganda materials, helping create a directly relatable medium. Facts and statistics, using pictograms and diagrams to make them easier to understand, were also widely used to back up positive statements about how well Britain was coping with war.

“As well as provoking emotional responses, the Ministry of Information used exhibitions to teach new skills,” says Harriet. “Many exhibitions focused on practical skills such as growing and preparing food, sewing and mending, and fuel efficiency. Displays often combined photographs and photomontages in clever ways, such as implying garden pests and Axis powers were a common enemy by adding Nazi insignia to images of slugs,” she explains. “Images were often accompanied by lively instructional verses.”

THE ROLE OF EXHIBITIONS

Not just consigned to art galleries, these exhibitions could be found in libraries, bomb sites, church halls, train stations and workers’ canteens. They were meant to provide an accessible way of sharing messages and many exhibitions toured more rural areas, so they could reach a wider audience. “Historians often think of exhibitions as a portal into a particular issue,” says Harriet. “In the case of the ones I’m looking at, they were being used to raise explicitly political points. But exhibitions can also help shed light on the development of artistic styles or show how a nation represented itself to the rest of the world.”

Because they were accessible for viewers, these exhibitions could also be an effective way for marginalised people to broadcast their perspectives. “Many influential architects and designers from Czechoslovakia, Austria, Germany, Hungary and other parts of Europe took refuge in London during the 1930s,” says Harriet. “They directly shaped the wider design cultures of Britain, through contributions to architecture, graphics and textiles.” The early twentieth century marked a time when rising totalitarian regimes, in particular Fascists and Nazis, were becoming increasingly hostile to artistic expression that either directly or indirectly went against the leading political ideology. As a result, many artists moved to western Europe, including Britain, where they could express themselves more freely.

POLITICAL EXPRESSION

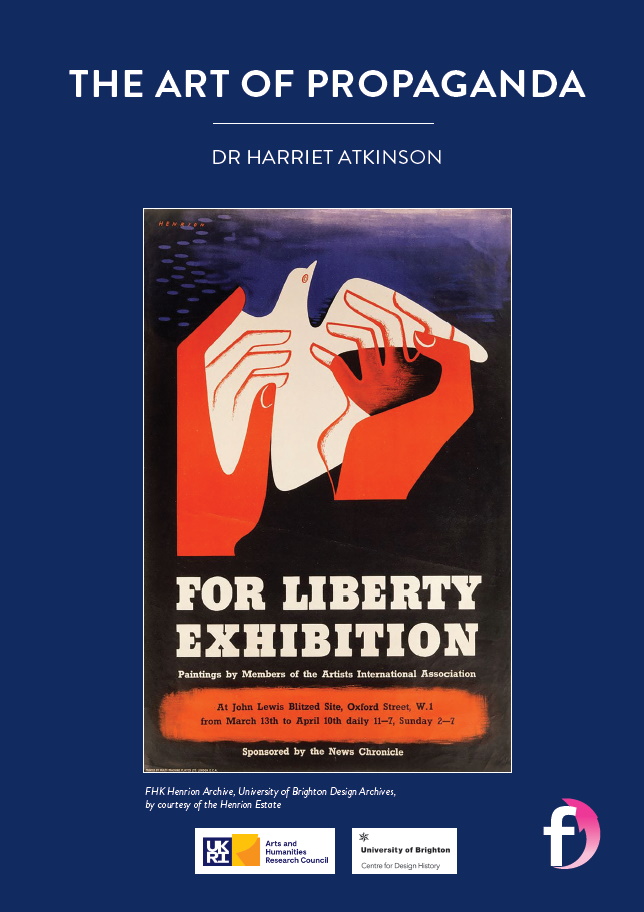

Harriet is investigating how different groups used exhibitions as platforms for expressing their political views. One group she is interested in is the Artists International Association (AIA), which was founded in 1933 by a collection of strongly left-wing artists, including some Communist Party members. “Some AIA members had spent time in the Soviet Union, where they were impressed by the central role of artists in imagining a new, utopian society,” says Harriet. “However, the experiences of World War II changed their perspectives, and many ended up losing their radical edge.” In fact, the post-war boom saw many artists and designers joining commercial practices.

Another significant group was the Free German League of Culture, founded in London in 1938 by refugees from Nazi Germany. Despite the relative liberality of Britain, they were still treated with caution by the government. “This group was also left-aligned and was closely monitored by MI5, who suspected that this organisation and their exhibitions were a front for a more seditious project,” says Harriet.

LOOKING DEEPER

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM182

When was the last time you saw an image – maybe an Instagram post or a meme shared in a WhatsApp group – that portrayed a strong opinion? In our modern age of digital communication, chances are very recently! Now, think about the last time you saw an image that portrayed a strong political opinion or idea. What message was it conveying? Was it persuasive? Did you agree with the message? Did you trust the message and share it with others? Did you question whether the image – and the message it was conveying – was accurate or ‘fake’? It is easy for us to link the concept of propaganda to the era of world wars, but it could be said that social media has made us all more politically active and, with the rise of misinformation, the use of propaganda more commonplace.

Dr Harriet Atkinson, Senior Lecturer at the University of Brighton in the UK, is a historian of art and design currently writing a history of political propaganda exhibitions that took place in Britain in the 1930s and 1940s. “For a long time, I’ve been interested in how governments use design to influence ideas about the nation, to persuade people of their point of view and to connect across national boundaries,” says Harriet. The exhibitions she is looking at were aimed to provoke a particular response, such as national pride or anti-fascist feeling – not so different from some of the images we see today.

“This particular area of British Modernism has been overlooked until now – possibly because it bridges several different disciplines, and the evidence for the exhibitions is hard to come by,” says Harriet. These exhibitions tended to be short-lived and records of their existence can be scant and scattered. Moreover, researching their impact on society involves piecing together many seemingly unrelated pieces of evidence. Harriet spends her days poring over archive material to build the picture of how these exhibitions arose and what they represented.

A TIME OF WAR

When World War II broke out, the British government’s Ministry of Information used exhibitions as a tool for generating particular emotions in the British public. “These exhibitions were designed to inspire audiences to live more efficiently, to take pride in the war effort, and to provoke anger against their enemies,” says Harriet. The rise in photography meant that images of real people and situations could be incorporated into propaganda materials, helping create a directly relatable medium. Facts and statistics, using pictograms and diagrams to make them easier to understand, were also widely used to back up positive statements about how well Britain was coping with war.

“As well as provoking emotional responses, the Ministry of Information used exhibitions to teach new skills,” says Harriet. “Many exhibitions focused on practical skills such as growing and preparing food, sewing and mending, and fuel efficiency. Displays often combined photographs and photomontages in clever ways, such as implying garden pests and Axis powers were a common enemy by adding Nazi insignia to images of slugs,” she explains. “Images were often accompanied by lively instructional verses.”

THE ROLE OF EXHIBITIONS

Not just consigned to art galleries, these exhibitions could be found in libraries, bomb sites, church halls, train stations and workers’ canteens. They were meant to provide an accessible way of sharing messages and many exhibitions toured more rural areas, so they could reach a wider audience. “Historians often think of exhibitions as a portal into a particular issue,” says Harriet. “In the case of the ones I’m looking at, they were being used to raise explicitly political points. But exhibitions can also help shed light on the development of artistic styles or show how a nation represented itself to the rest of the world.”

Because they were accessible for viewers, these exhibitions could also be an effective way for marginalised people to broadcast their perspectives. “Many influential architects and designers from Czechoslovakia, Austria, Germany, Hungary and other parts of Europe took refuge in London during the 1930s,” says Harriet. “They directly shaped the wider design

cultures of Britain, through contributions to architecture, graphics and textiles.” The early twentieth century marked a time when rising totalitarian regimes, in particular Fascists and Nazis, were becoming increasingly hostile to artistic expression that either directly or indirectly went against the leading political ideology. As a result, many artists moved to western Europe, including Britain, where they could express themselves more freely.

POLITICAL EXPRESSION

Harriet is investigating how different groups used exhibitions as platforms for expressing their political views. One group she is interested in is the Artists International Association (AIA), which was founded in 1933 by a collection of strongly left-wing artists, including some Communist Party members. “Some AIA members had spent time in the Soviet Union, where they were impressed by the central role of artists in imagining a new, utopian society,” says Harriet. “However, the experiences of World War II changed their perspectives, and many ended up losing their radical edge.” In fact, the post-war boom saw many artists and designers joining commercial practices.

Another significant group was the Free German League of Culture, founded in London in 1938 by refugees from Nazi Germany. Despite the relative liberality of Britain, they were still treated with caution by the government. “This group was also left-aligned and was closely monitored by MI5, who suspected that this organisation and their exhibitions were a front for a more seditious project,” says Harriet.

LOOKING DEEPER

Some exhibitions were on a grand scale, and their impacts still resonate today. “Picasso’s striking anti-war painting Guernica visited Britain in 1938 as part of a campaign to raise funds to support the anti-fascist grouping in the Spanish Civil War, and major wartime propaganda exhibitions such as The Army were very well-attended,” says Harriet. “Other exhibitions were tiny and only seen by small audiences, in venues such as local shop windows.” The task of deciphering the impacts of exhibitions large and small on the mentality of wider society is challenging, but through both factual reports – such as visitor numbers – and personal accounts or reviews of these exhibitions, Harriet can gradually build up an informative picture.

Studying history reveals fascinating insights into how society once was, but it also shines a light on how we are living now. Harriet’s research reminds us of the importance of art and visual communication in reflecting and shaping societal values. The next time you look at an image online, think carefully about the message it is conveying and be a critical viewer. Do you trust the message? Is any photography used genuine? How have elements of art and design been used for a specific effect? Whether you feel the message is positive or not, ask yourself, are you being influenced through the ‘art of propaganda’?

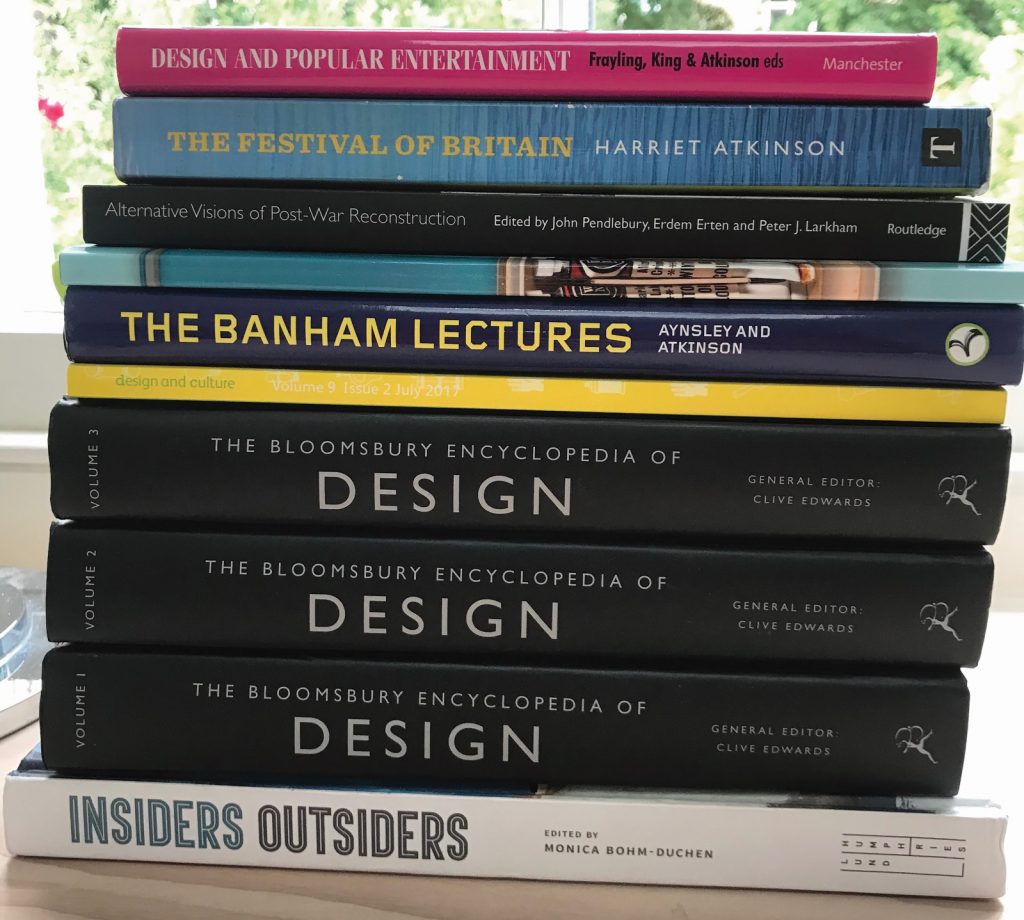

DR HARRIET ATKINSON

DR HARRIET ATKINSON

Senior Lecturer, School of Humanities and Applied Social Science, University of Brighton, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: History of Art and Design

RESEARCH PROJECT: Researching modernist exhibitions in Britain for propaganda and resistance, from 1933 to 1953

FUNDER: ‘“The Materialisation of Persuasion”: Modernist Exhibitions in Britain for Propaganda and Resistance, 1933 to 1953’, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council Leadership Fellowship, Project Reference: AH/S001883/1.

DR HARRIET ATKINSON

DR HARRIET ATKINSON

Senior Lecturer, School of Humanities and Applied Social Science, University of Brighton, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: History of Art and Design

RESEARCH PROJECT: Researching modernist exhibitions in Britain for propaganda and resistance, from 1933 to 1953

FUNDER: ‘“The Materialisation of Persuasion”: Modernist Exhibitions in Britain for Propaganda and Resistance, 1933 to 1953’, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council Leadership Fellowship, Project Reference: AH/S001883/1.

ABOUT THE HISTORY OF ART AND DESIGN

Harriet is a historian of art and design, a discipline which gives key insights into everything from societal norms to radical ideas, and how they influenced art and design. Through examining the objects and artworks created by generations past, she is granted a window into the mentalities that shaped the world into what we see today. Harriet explains more about her work.

I enjoy thinking about images and objects, and they are the central focus of my research. I love working on my own and have been fortunate to travel to archives around the world – I’ve spent time in Washington and New York, for instance. I’m also lucky to work with and meet many fantastic people who share my interests. I love attending conferences in different places. Having conversations with the people I meet there is really stimulating.

My typical research day has changed significantly given the effects of the pandemic. Pre-COVID-19, I worked in the British Library every day, reading books and periodicals and visiting the library’s extensive archives. Since the pandemic struck, I’ve transitioned to finding material online so I can work from home, with occasional visits to libraries and archives to gather new material. I’m very ritualistic about how I work – starting at a set time and having set periods within which to focus on my work.

Archive research is a slow and steady process. I begin by analysing drawings, photographs, plans, letters, interviews or minutes of meetings, depending on what evidence is available, and gradually build broader ideas around them. Little by little, the wider themes start to become apparent, and I can make connections between different pieces of evidence. Some days, I focus on small examples, whereas on other days I tackle the bigger ideas.

My academic work allows me to delve into many topics I find interesting. I have a new podcast underway called Graphic Interventions, where I interview contemporary artists, designers and collectives about how they make political comments through their graphic work. I am planning to combine what I learn from this podcast and the book on earlier exhibitions to create a documentary film about politically-engaged artists and designers in the early twentieth century.

I think that future historians will be interested in design’s response to the pandemic and to climate change. We’re only just starting to understand both of these at the moment. I also think that future historians will need to make sense of the impacts of so much of our everyday lives moving online during 2020.

EXPLORE A CAREER IN THE HISTORY OF ART AND DESIGN

• University is not the only pathway for a career in art and design. For instance, Artswork coordinates creative apprenticeships, such as in theatres or galleries, in southern England.

• The University of Brighton has an extensive public outreach scheme for schools and young people in south-east England. For undergraduates, their Active Student programme helps students gain experience of relevant work and volunteering alongside their degrees.

• Given the breadth of career paths within this subject area, salaries can vary widely. As a ballpark figure, the average historian salary in the UK is £37,000.

Harriet says there are several academic routes to her research area. At school and at university, this can involve studying humanities subjects such as history or history of art, or creative subjects such as design and technology, art or graphic design. Harriet says that all these subjects offer a good grounding for entering the research field.

HARRIET’S TOP TIPS

01 Be actively interested in the subject. Go to exhibitions, read books about art and design, watch documentaries and films and go to free talks in person or online.

02 Volunteering or internships, such as with heritage organisations or museums, can be a really good way of getting a sense of the field and whether you might like to pursue a career in it.

HOW DID HARRIET BECOME AN ART AND DESIGN HISTORIAN?

WHAT WERE YOUR INTERESTS AS A CHILD?

I was interested in art and design from a young age. At primary school, I was lucky enough to go on school trips to art galleries and found looking at the art there really exciting and inspiring. I also thought a lot about why the things we use every day – such as cutlery, chairs, traffic lights or road signs – look the way they do! As I got older, my interest grew into considering how governments use culture to bring people together, to improve well-being and to inspire national pride.

WHAT INSPIRED YOU TO PURSUE A CAREER IN YOUR FIELD?

I remember visiting the National Gallery with my school as a young child, and being bowled over by Titian’s paintings of mythology. My interest in visual material was encouraged by my grandmother, who was an artist, and by my excellent secondary school art teacher, Mr Risoe. I loved the research process during my master’s and although I hadn’t planned on pursuing a career in academia, after nearly a decade working in arts policy and funding, I realised that my great passion was for research and writing.

WHAT ATTRIBUTES HAVE MADE YOU SUCCESSFUL AS A RESEARCHER?

Single-mindedness, persistence, and the ability to motivate myself even when it feels like there’s no end in sight. I genuinely love exploring archives, poring over dusty folders on my own! I also enjoy working collaboratively, editing books or planning conferences and workshops with others. Academia involves a lot of multi-tasking, and most academics find themselves juggling teaching, admin and research. There is also a lot of time spent filling in funding forms, which is a skill in itself.

HOW DO YOU SWITCH OFF FROM WORK?

Exercise is a very good way to switch off. I love running, walking, cycling and freshwater swimming. Spending time with my three children also naturally involves switching off from work.

WHAT ARE YOUR PROUDEST CAREER ACHIEVEMENTS SO FAR?

My current AHRC Fellowship has granted me the most extraordinary opportunity to investigate a whole series of ideas and interests I’ve held for a long time. The completion of my PhD, published in 2012, was another high point. Alongside my paid work as an academic, over the past 30 years I have always taken on voluntary positions in charities that make a contribution to my local community or to my communities of interest. This can be every bit as hard as paid work but is unremunerated and often unacknowledged. I’m proud to have kept this going.

Do you have a question for Harriet?

Write it in the comments box below and Harriet will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)