The milk of human kindness

Dr Natalie Shenker is the co-founder of the Hearts Milk Bank – a UK-based charity that provides donor human milk to vulnerable babies who, for whatever reason, are unable to receive milk from their birth mother

TALK LIKE A HUMAN MILK RESEARCHER

DONOR HUMAN MILK (DHM) – breast milk donated by a woman who is not the birth mother of the baby receiving it

FORMULA MILK – liquid feed for babies, usually based on cow’s milk and supplemented to meet nutritional needs

MASTECTOMY – the removal of a breast, usually due to breast cancer

MATERNAL MILK – breast milk provided by a baby’s birth mother

NECROTISING ENTEROCOLITIS (NEC) – a condition in which some or all of the gut becomes inflamed and can die

NEONATAL INTENSIVE CARE UNIT (NICU) – the hospital unit where premature or very ill newborn babies are cared for

PREMATURE – a baby born before the 37th week of pregnancy (pregnancy usually lasts between 37 and 42 weeks)

When you think about lifesaving donations, you might think of blood or organs, but you probably do not think about milk. However, for the most vulnerable babies, born prematurely or with other health conditions, not being fed with human milk can risk their life. There are many reasons why a baby might not be able to receive milk from their birth mother, and in these situations, milk banks can provide lifesaving donations of human milk.

WHAT IS MILK?

Milk is produced by all mammals to feed their young and support the development of their immune system. Crucially, each species has milk specifically evolved to meet the needs of their own young, and so species-specific milk is important for feeding any mammalian infant.

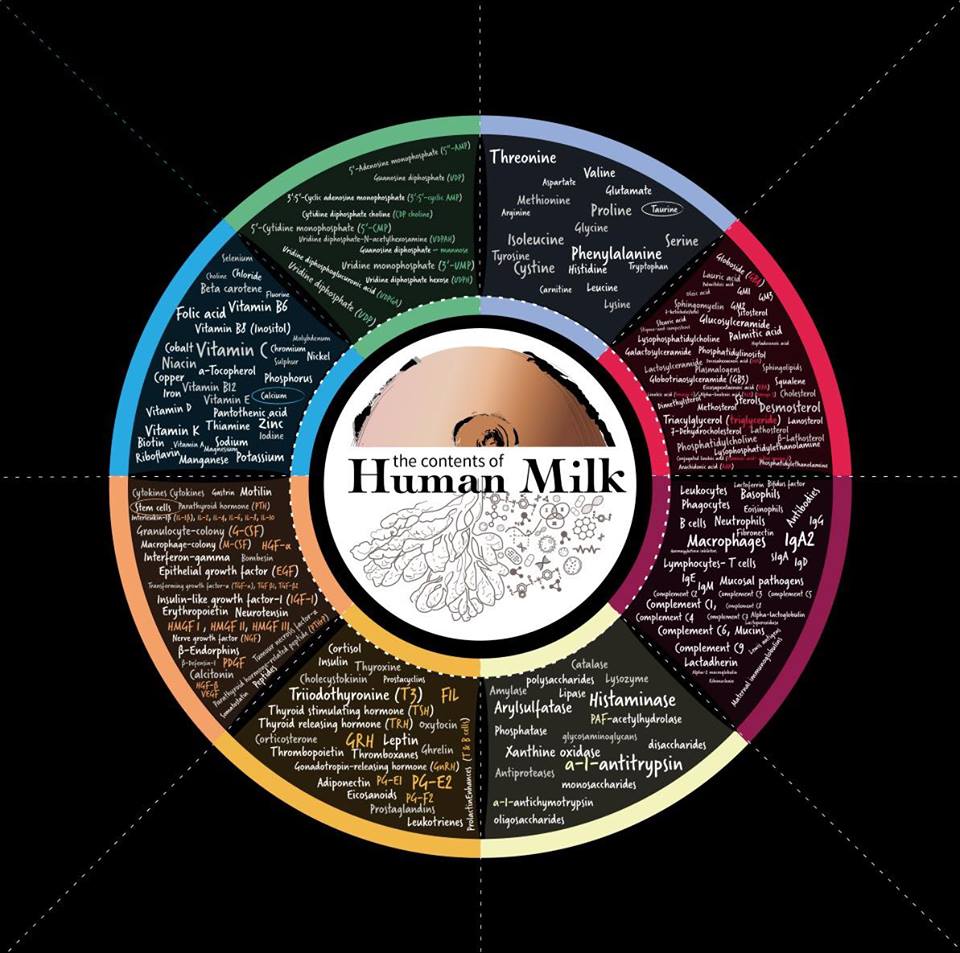

Biochemically, human milk is very different to that produced by other mammals. Highly specialised fatty acids support central nervous system neurons to make connections in the infant brain, which develops so rapidly over the first year. Over 100 modified sugars, called human milk oligosaccharides, have multiple functions that support immune system, gut and brain development. Human milk even contains an enzyme which reacts with saliva in the mouth to destroy harmful bacteria, cleaning new teeth to prevent plaque.

Maternal milk is tailor-made to meet the needs of the baby. The composition of human milk varies hugely. Antibodies in milk are produced within hours of exposure to pathogens. The hormonal content changes over a 24-hour cycle, helping babies develop a diurnal rhythm, and even varies over the course of a single feed. In hot and humid weather, milk will have more water, and some immune components are only produced at certain times of the year. Formula cannot replicate this responsiveness or immune protection, but if mothers face breastfeeding challenges, families have little choice but to feed their baby with formula.

Dr Natalie Shenker, a medical researcher at Imperial College London, hopes to change this. Along with Gillian Weaver, a nutrition expert who specialises in human milk banking, she founded the Hearts Milk Bank, where she not only provides an essential service for mothers and babies, but also conducts research to understand how more families can be supported by milk banks. The chief aim of Hearts is to provide every vulnerable baby with the opportunity of being fed with human milk, while ensuring mothers have the best support to reach their own breastfeeding goals.

HOW DOES A MILK BANK WORK?

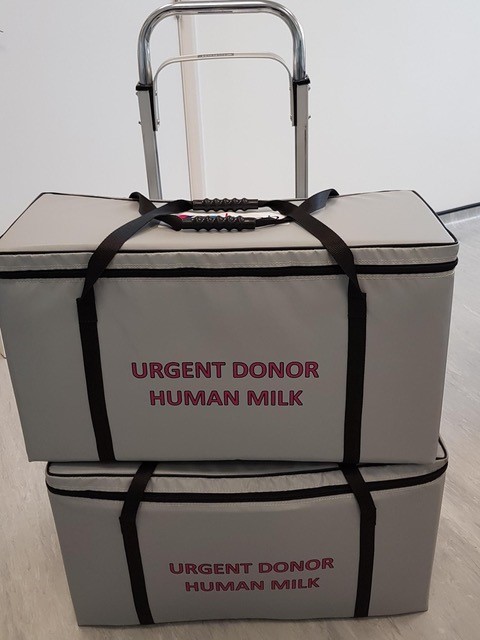

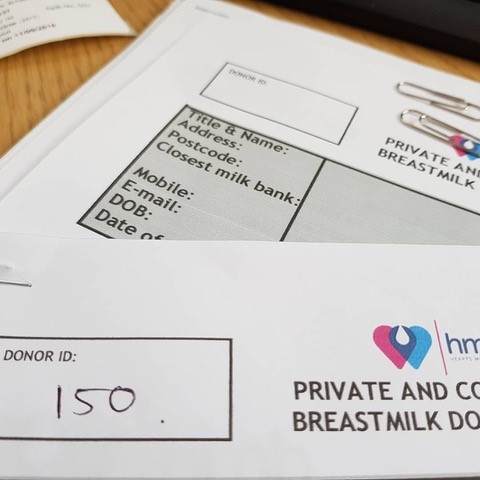

A milk bank is a lot like a blood bank, and the process is similar to the blood transfusion service. “We recruit mothers who have extra milk,” explains Natalie. “There are lots of reasons why mums may build up an oversupply of milk and our teams help them to manage this.” Each mum undergoes extensive health screening before donation to identify any factors that could affect the milk (such as smoking). This includes blood tests for HIV, hepatitis B and C, syphilis and HTLV. Mothers pump milk and keep it in their home freezer, until volunteer blood bikers collect the frozen milk from across the country and transport it to Hearts. Once defrosted, the milk is pasteurised and tested for bacteria to ensure it is safe for use. “Hospitals who need milk in Neonatal Intensive Care Units (NICU) are always the priority to receive our donor milk,” says Natalie. “Any surplus is used for mothers facing breastfeeding challenges.”

WHY MIGHT PREMATURE BABIES REQUIRE DONOR HUMAN MILK?

When a baby is born prematurely, the mother’s body may not yet be ready to produce milk. In addition, delivering a baby prematurely is extremely stressful, and stressed mothers often struggle to produce milk. Sometimes, mothers may be very ill themselves after a premature birth, and so unable to feed their newborn baby. In these instances, babies need to be given milk until their mother can produce enough for their needs. Usually, this substitute is cow’s milk-derived formula.

However, premature babies have not completed their development process in the womb, so their brain, intestines and immune system are all much weaker and under-developed. This means they are at greater risk of harm from being fed non-human milk. Necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) is a serious condition that causes the gut to die. Premature babies are much more likely to develop NEC, and this risk increases if the baby is formula fed. Between 25-40% of babies who develop NEC will die.

As well as supporting the mother, by acting as a bridge to breastfeeding, donor human milk (DHM) can be used like a medicine in this situation. DHM will never be as good as the mother’s own milk, but it greatly reduces the risk of NEC and other complications of premature birth as it is species-specific.

WHY MIGHT FULL-TERM BABIES REQUIRE DHM?

Prior to the establishment of Hearts, only a handful of full-term babies in the UK had ever received DHM. “Yet there are lots of reasons why mums of full-term babies may not be able to produce a full milk supply,” says Natalie.“They might have had a difficult birth or have an underlying medical condition. In most cases, with the right support, women will go on to produce a full supply. If that gap can be bridged by donor milk, our research is showing that those mums are more likely to go on to breastfeed. They are more likely to see this as part of a supportive journey that they are on to establish a full milk supply.”

Other women may never be able to breastfeed. They may have had a mastectomy to remove breast tissue due to cancer, or they may be undergoing chemotherapy. “Donor milk can make a huge difference in these cases,” says Natalie. “A frequent comment from mothers diagnosed with cancer during pregnancy is that they worried more about how they would feed their baby than their own prognosis. Our research is showing that being able to access DHM can help mothers come to terms with this loss and reduce anxiety and depression.”

WHAT RESEARCH IS NATALIE ENGAGED IN?

“The fabulous thing about working in a field of science where there’s almost no research published is that you’ve got plenty to work on!” says Natalie. “When we started, there were only two scientific papers published about the composition of human milk after the first six months of a baby’s life. We needed to understand this to know whether mothers could donate milk if their babies were older.”

As a medical researcher, one of Natalie’s current focuses is on the changes in the composition of maternal milk as a baby grows. To collect pilot data before beginning a larger study, Natalie asked women who were breastfeeding babies of any age to express milk for analysis. This provided a snapshot of milk composition for feeding children aged three months to four and a half years. “We had a day at Imperial College London where 120 women turned up with all their babies and toddlers,” she says. “There were young children everywhere – it was total chaos, but we made some amazing discoveries, including that human milk remains nutritionally complete far beyond six months after birth.”

After analysing the composition of maternal milk being fed to children of different ages, the research team discovered that most of the metabolites and fatty acids in human milk do not change in the first two years of an infant’s life.

Ultimately, human milk evolved to support infant development and immune protection. With many reasons why a baby may not be able to receive milk from their birth mother, donor human milk is hugely important for providing a positive start in life for many babies.

DID YOU KNOW…?

• Mammalian species developed the ability to produce fluid from specialised glands more than 200 million years ago, when mammals hatched from eggs. This milk was little more than water with a few anti-microbial sugars, designed to prevent the eggs from drying out and protecting them from bacteria, fungi and viruses.

• The word mammal comes from the Latin word ‘mamma’, meaning the ducts containing milk-producing cells.

• High-value racing horses will be fed with another horse’s milk if the mother is unable to feed the foal, as the foal’s development depends on species-specific milk.

• The stress hormone, cortisol, impacts the production and effectiveness of prolactin and oxytocin, hormones that control milk production and release, which is why stressed mothers may struggle to produce milk.

• About 70% of milk at Hearts comes from mothers who are at home with their babies. The remaining 30% of milk comes from mothers whose babies are in NICU. The mum will pump milk to maintain a supply, but their baby may only require a fraction of this as they are so small, or nothing at all if they are very sick.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM328

DR NATALIE SHENKER

DR NATALIE SHENKER

Research Fellow, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, UK

Co-founder of the Hearts Milk Bank

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Implementation science of human milk banking

RESEARCH PROJECT: Researching the properties of human milk and how donated milk can protect the health of infants and mothers and support breastfeeding journeys

FUNDER: UK Research and Innovation (UKRI)

ABOUT MEDICAL RESEARCH

Medical research is the quest to understand human health and diseases, which ultimately leads to the development of improved treatments. Researchers work across the entire range of medical topics, which means you can identify which aspect is of interest to you and tailor your studies accordingly.

Medical researchers may find themselves working in a laboratory conducting experiments, on the frontline of the NHS, or running clinical trials testing new drugs. Perhaps, like Natalie, you might establish your own organisation to address whichever health-related issue you are passionate about.

WHAT ARE THE REWARDS OF MEDICAL RESEARCH?

Natalie’s research is split between fundamental science and performing clinical trials to establish the impacts of the science. “The most rewarding thing is watching the translation of my research into real impact that helps families,” explains Natalie. “It is phenomenal to be watching rapid changes in clinical care and even shifts in breastfeeding, in part because of our work.”

WHAT CHALLENGES DID NATALIE FACE WHEN ESTABLISHING THE HEARTS MILK BANK?

“Culture, prevailing medical views and public perception have been huge challenges,” says Natalie. The UK has some of the lowest breastfeeding rates in the world, with only one in 200 women breastfeeding by the time their baby is one year old1. “As a society, we don’t really want to talk about the issues women face during breastfeeding,” says Natalie.

Medical researchers studying human milk must understand the cultural perceptions and industry influence associated with breastfeeding. The study of human milk was not a government priority so to gain funding, researchers have had to rely on the formula industry. Companies want to understand the composition of human milk so they can alter their cow’s milk formula and claim it is similar to breast milk. “The truly unique thing we’re doing with Hearts is we’ve never accepted money from formula companies,” explains Natalie. “So, funding has been a huge challenge. Hearts was initially funded by crowdfunding, bake sales and people running marathons! But we had a clear vision of what could change if we persevered.”

WHAT ISSUES WILL THE NEXT GENERATION OF MEDICAL RESEARCHERS FACE?

“We need formula milk, because there aren’t enough human milk banks and because many women struggle with breastfeeding,” explains Natalie. “I initially used formula to feed my own child. But knowing what I know now, my decisions would have been different if I had had more choices.” However, it is important that there are pathways into the field of medical research that are not influenced by industry. Funding needs to be available from sources that do not have potential ulterior motives in the research, so-called conflicts of interest. “I think the next generation needs to be a lot more aware and critical of where they are taking funding from,” says Natalie. “I believe we are beginning to witness this change.”

1. Data from the last infant feeding survey in 2010

Natalie is refreshingly relaxed when it comes to suggesting which subjects to take. “I think that you should study whatever you love – whatever gets you out of bed in the morning and wherever your talents lie.”

A typical pathway into medical research involves science and mathematics A-levels and an undergraduate degree in medicine or a related field (e.g., biomedical science, pharmacology, immunology, biochemistry). Most researchers will then gain a master’s or PhD.

EXPLORE CAREERS IN MEDICAL RESEARCH

Prospects (www.prospects.ac.uk/job-profiles/research-scientist-medical) and Target Careers (www.targetcareers.co.uk/career-sectors/healthcare-and-veterinary-medicine/1014251-medical-research-jobs-and-qualifications) have sections dedicated to medical researchers, containing a wealth of information on how to embark on a career in this area, including what qualifications you will need to gain and what salary you can expect.

The Medical Research Council (www.ukri.org/councils/mrc) has a section on its website dedicated to skills and careers (www.mrc.ukri.org/skills-careers) where you can learn more about careers in medical research and the support available to students.

HOW DID NATALIE BECOME A MEDICAL RESEARCHER?

DID YOU ALWAYS WANT TO WORK IN MEDICINE?

I was always aware I really wanted to contribute to a better, healthier world. Medicine kept so many options open as it is such a diverse profession. After years specialising in paediatric surgery, it became clear that I was most passionate about using research and practical interventions to help improve societal health.

WHAT INSPIRED YOU TO BECOME A SCIENTIST?

I was always really fascinated by exploration, the idea of people literally going out into the unknown but having adventures and facing down challenges along the way. Science brings that same excitement, but I get to work embedded within communities that can directly benefit from my research.

WHAT PERSONAL QUALITIES HAVE MADE YOU SUCCESSFUL AS A SCIENTIST?

Grit and determination. I’ve had some really challenging times in life but learning to bounce back and focus on the important things has been the most valuable lesson of my life. Being able to carry on when things go wrong is important, and now I understand that whenever negatives happen, there is always a positive, no matter how far you’ve got to dig down to find it.

WHAT DO YOU ENJOY DOING OUTSIDE OF YOUR WORK?

Life has been pretty hectic for the last few years, but we’ve just moved into the countryside. We’ve adopted a rescue puppy who is keeping us all on our toes and teaching us all the joys of 6 am walks.

WHAT ARE YOUR PROUDEST CAREER ACHIEVEMENTS SO FAR?

Winning the UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship was undoubtedly the turning point for everything. It shone a light into the whole sector of infant feeding, showing that the work in this space is really important. But what makes me proudest is hearing stories from all the families who are benefitting from Hearts, talking with doctors across the world looking to implement similar programmes, and knowing that all our work here is helping to contribute to that.

WHAT ARE YOUR HOPES FOR THE FUTURE?

My main hope for the future is that the next generation are empowered to take on challenges – we face so many. And if school-leavers have the knowledge that few jobs will have more impact on the health of individuals than being a lactation consultant, breastfeeding medicine specialist or milk bank technician, then my work will be done.

NATALIE’S TOP TIPS

01 Follow your passions! Whatever your passions are, they can be incorporated into medical research or whatever role you choose.

02 Be a critical thinker – Who is telling you information? What might be their motivations? What are your own unconscious biases?

03 Transferable skills such as teamwork, collaboration and building trust are really important in medical research, so work on developing these as much as possible.

READ THE STORIES OF SOME MOTHERS AND BABIES WHO HAVE BENEFITTED FROM THE HEARTS MILK BANK

ANNA AND ALBY’S STORY

Anna was diagnosed with leukaemia when she was 12 weeks pregnant. “I was scared for myself but also for the future of my growing baby,” she says. “Despite it probably seeming like a small detail when I’d just been diagnosed with a life-threatening illness, the thought of not being able to breastfeed was one of the factors that most upset me.”

Anna had heard of milk banks, and so contacted a few to ask if they could provide milk for her baby. But each told her that they could only donate milk to premature or unwell babies, or that she would have to obtain her own funding through an NHS funding board, a complicated and stressful task for someone with leukaemia and pregnant.

But then she contacted Hearts Milk Bank. “The response from Hearts was different,” Anna says. “They were understanding and flexible and have slashed through all the funding red tape.” Hearts do all their own fundraising, removing the pressure from pregnant women and new parents to supply money if they need to receive milk. “The process was so easy, and they provided me with donor milk for the first month of my baby’s life which was more than I could have hoped for.”

Anna was induced at 37 weeks and was able to breastfeed for three days before starting chemotherapy treatment. “It was lovely to have those days of that closeness with my little boy, Alby.” She found it emotionally hard to stop breastfeeding when her chemotherapy began. “But being able to continue giving my baby breast milk made a huge difference to how upsetting I found that difficult time.”

“I felt overwhelmed by the huge generosity of all the women who’d taken the time and care to make this milk available to my baby and many others,” says Anna, who remembers how much effort it was to express milk when she had her first baby. “I will always feel grateful to the team at Hearts, who were incredibly kind and supportive throughout, and to all the women who donate milk to them and everyone who supports them financially, for giving my baby the best possible start despite really difficult circumstances.”

KIM AND INDIGO’S STORY

When Kim lost her uncle to coronavirus, she became terrified of the thought of giving birth in a hospital, so decided to have a home birth. Despite her labour being slow to progress, she felt safe and comfortable at home. But then, her baby had a bowel movement before he was born.

Kim was rushed to hospital as her little boy, Indigo, was seriously ill with Meconium Aspiration Syndrome. “It was heart-breaking to see him fighting for his life,” she says. “I was only able to hold him once during this entire time and I couldn’t breastfeed him at all.”

Indigo spent three weeks in hospital, wired up to machines and fed through a syringe. Kim was desperate to breastfeed him, to give him the strength and immunity that he needed through her milk. But when Indigo was strong enough to go home, Kim wasn’t producing enough milk, despite pumping while he had been in hospital to maintain her supply. “Indigo couldn’t stomach formula milk and so he started to rapidly lose weight,” says Kim.

Kim’s midwife told her about donor milk, which is when Kim discovered Hearts Milk Bank. “We received our first delivery of donor milk a few days later and it was a game changer,” she says. “It gave me time for my milk supply to build up and gave Indigo the strength he needed to get through those difficult first few weeks.”

LUCY AND ADA’S STORY

Lucy wasn’t expecting to become pregnant again. She had said goodbye to the baby stage of parenthood and had sent her youngest child off to school. Then, after having a double mastectomy, she discovered that she was indeed pregnant once more. “After the initial shock cleared, the next thing I thought was, ‘how am I going to feed this baby?’” Lucy says. “I had no breasts.”

Breastfeeding is really important to Lucy, who had breastfed her other children for three years each. Not only was Lucy interested in the science behind breastfeeding, but she had trained as a peer supporter to help other mothers breastfeed and she volunteered at her local breastfeeding café. “The thought of not being able to breastfeed this baby truly broke me.”

Lucy knew she needed to find donor milk for her baby, but her application to the NHS funding board was rejected on the basis that it was ‘not medically necessary’. “I disagree with that assessment,” says Lucy. “I live with diabetes, and it is scientifically proven that breastfeeding protects children from developing diabetes in later life, amongst other conditions. There is also the mental health aspect of breastfeeding which I think is just as valid as my physical health.”

So, Lucy was relieved to discover the Hearts Milk Bank and hear that she could still access donor milk for her baby. When her waters broke early (indicating she was going into labour earlier than expected) matters were complicated because it meant her baby, Ada, was born before Lucy had received her milk supplies from Hearts. Instead, Lucy’s husband had to travel to collect the milk.

“I was so happy to see our freezer filled with donor milk just for my baby, who was still in hospital at this point,” Lucy says. Initially, Ada was fed 1 ml of donor milk every hour through her feeding tube. By the time she was discharged from hospital, she was taking 70 ml every 3 hours. “Ada absolutely thrived on donor milk!” says Lucy. “I am so happy I could do this for my baby.”

Do you have a question for Natalie?

Write it in the comments box below and Natalie will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)