The molecular mechanisms behind a devastating disease

Huntington’s disease is a serious genetic disorder that causes problems with movement, thinking and mood, and eventually leads to death. It is known to be caused by an error in a single gene, but the molecular mechanisms that are affected by this error are not fully understood. At the University of Minnesota in the US, Dr Rocio Gomez-Pastor is studying these mechanisms, with the hope that her findings will inform new, innovative ways to treat the disease.

Talk like a neuroscientist

Huntingtin — the gene, and the protein it encodes, that causes Huntington’s disease when mutated

Huntington’s disease (HD) — a progressive, genetic brain disorder that causes neurons to degenerate over time, affecting thinking ability, mood and movement

Neuron — a nerve cell that transmits electrical signals to send messages between the brain and the body

Preclinical — the stage of medical research that happens before human testing (e.g., on cells or animal models)

Protein folding — the process where a linear chain of amino acids folds into the specific three-dimensional structure that allows a protein to fulfil its function

Protein homeostasis — the dynamic regulation of protein concentrations within a cell

Synapse — a junction where two nerve cells meet and a chemical signal is transmitted

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a devastating and ultimately fatal neurological condition that affects around 1 in every 10,000 people. Symptoms tend to begin appearing in middle age. “HD is an inherited brain disorder that is caused by a change in a single gene called huntingtin,” says Dr Rocio Gomez-Pastor of the University of Minnesota. “The mutated version of this gene contains a certain DNA sequence that repeats too many times.” This gene codes the huntingtin protein, so the mutation leads to an abnormal protein that accumulates in brain cells, disrupts their functioning, and eventually kills them. “Typically, the more repeats of this gene that a person has, the earlier and more severe the disease,” says Rocio.

Rocio is a neuroscientist who is focusing on molecular pathways associated with huntingtin. She is looking at how a certain molecular signal leads to further signals and is aiming to understand the eventual purpose of these signals in modifying and regulating activities within the cell. Her lab is studying the huntingtin protein, and how the way it interacts with molecular pathways differs when it is normal or mutated, to understand how exactly it can cause such damage. “Exploring how cells are disrupted may provide a promising avenue for developing effective therapies,” says Rocio. “HD is a terrible disease that urgently needs a cure.”

Balance in the brain

Proteins are encoded by our genes, and complex molecular mechanisms regulate their production and management, to ensure that levels of different proteins remain in the correct balance – a process known as protein homeostasis. “We’re studying how brain cells keep their proteins healthy and balanced, and what happens when this process fails,” explains Rocio. “By identifying the molecular pathways that restore protein balance and resilience, we aim to discover new strategies to slow or prevent HD progression.”

The sequence of amino acids within a gene defines the shape of the protein that it encodes via a process called protein folding. The shape of the protein determines its function, so mistakes in the gene can lead to malfunctioning proteins. Normal huntingtin is an essential protein, especially for neurons, thought to play a role in transporting molecules within cells, chemical signalling and even protein homeostasis itself. But when huntingtin is mutated, it disrupts these processes and interferes with other proteins. “We examine these molecular changes, such as how mutant huntingtin affects protein folding, and downstream effects, such as neuron survival, synaptic signalling and connectivity,” says Rocio.

Mixed signals

The Gomez-Pastor Lab is focusing on medium spiny neurons (MSNs), which are the brain cells most affected by HD. “MSNs control movement, coordination and some forms of cognition,” says Rocio. “We are particularly interested in how the mutant huntingtin protein disrupts communication between neurons.” Neurons communicate via synapses – the small ‘gaps’ between the cells that form the junctions in neural pathways. An electrical signal travels from one end of a neuron to the other. When it reaches the synapse, the cell transforms the electrical signal into a chemical signal, which travels across the synapse and activates the next neuron. “Synaptic signalling is essential for memory and other cognitive functions,” says Rocio. “Mutant huntingtin protein disrupts this process, which may explain the cognitive deficits that develop early in HD.”

To understand exactly what these disruptions mean at the whole-organism level, Rocio’s team studies mouse models: a normal control group and groups with different levels of huntingtin mutations. “We use animal models to connect these cellular changes to behavioural changes,” she says. A multidisciplinary approach, covering every aspect from the molecular level to the behavioural level, is essential to truly understand the disease. “HD affects the brain at every scale,” explains Rocio. “By combining molecular biology, cell biology and behavioural studies, we can gain a more complete understanding.”

From the lab to the clinic

The development of such a comprehensive understanding of HD could pave the way for new ways to treat and manage the disease. “There remains a critical need for a deeper understanding of the mechanisms that drive HD,” says Rocio. “By uncovering how mutant huntingtin disrupts protein homeostasis, neuron function and synaptic signalling, we hope to identify key pathways that can be targeted to protect vulnerable neurons.”

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM649

© Gomez-Pastor Lab

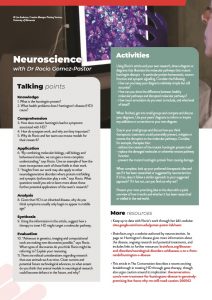

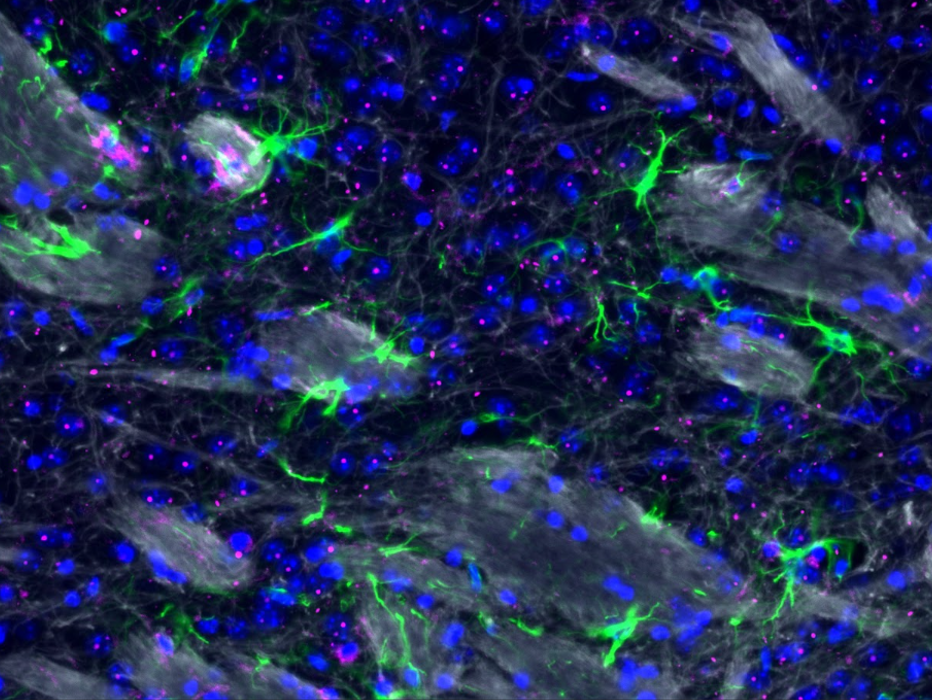

Centre: Brain imaging of neurons, astrocytes and myelin

© Gomez-Pastor Lab

© Gomez-Pastor Lab

© Gomez-Pastor Lab

© Gomez-Pastor Lab

So far, Rocio’s lab has identified key molecular pathways that are disrupted by mutant huntingtin – which reveals useful targets for therapies that could restore these pathways. “We have begun to develop and test small molecules to improve protein homeostasis and restore the cell’s natural protective mechanisms,” says Rocio. “These approaches have shown promise in preclinical models.” Her findings may also have applications beyond HD. “Insights from our work may also apply to other neurodegenerative disorders where protein misfolding and synaptic dysfunction play a role,” says Rocio. “This could lead to advances in treatments more broadly.”

With these findings in hand, the Gomez- Pastor Lab now aims to build on its research to identify ways to treat both motor and cognitive malfunctions associated with Huntington’s disease. “Our focus is on translating our findings into strategies to protect neurons in HD patients,” explains Rocio. “Ultimately, our goal is to develop therapies that are both effective and accessible for people living with this disease.”

Dr Rocio Gomez- Pastor

Dr Rocio Gomez- Pastor

Associate Professor, Gomez-Pastor Lab, Department of Neuroscience, University of Minnesota, USA

Field of research: Neuroscience

Research project: Studying the molecular mechanisms of neurodegeneration and cell death in Huntington’s disease

Funder: US National Institutes of Health (NIH)

About neuroscience

Neuroscience is a broad field that involves the study of the structure and function of the brain and broader nervous system. “Neuroscience can be highly collaborative and multidisciplinary,” says Rocio. “It combines insights from molecular biology, neurochemistry and therapeutics, to name a few fields.”

Rocio’s particular speciality focuses on the molecular pathways behind neurological diseases, which has direct applications for improving well-being. “We have the opportunity to uncover the fundamental mechanisms that drive neurodegenerative diseases,” says Rocio. “It is incredibly fulfilling to see how discoveries at the molecular and cellular levels can translate into strategies that improve patients’ lives.”

A growing base of knowledge and a dazzling array of new and emerging technologies are helping neuroscientists make discoveries that once seemed unreachable. “Advances in genetics, imaging and computational tools are making new discoveries possible,” says Rocio. “This will open doors for new therapies to be developed.” The next generation of neuroscientists will be at the forefront of this wave of discovery.

And the real-world impact of such discoveries is self-evident. Recently, for example, studies have identified potential cures for Huntington’s disease – a possible lifeline for tens of thousands of people. “Ultimately, knowing that our research could contribute to treatments that enhance quality of life makes the challenges and long hours in the lab deeply worthwhile.”

Pathway from school to neuroscience

Rocio recommends building a strong foundation in science, mathematics and critical thinking at school.

At university, a wide range of choices can lead to a career in neuroscience, depending on your interests. “While biology, chemistry and psychology are helpful, it’s important to remember that neuroscientists come from a wide range of backgrounds including engineering, computer science and the social sciences,” says Rocio.

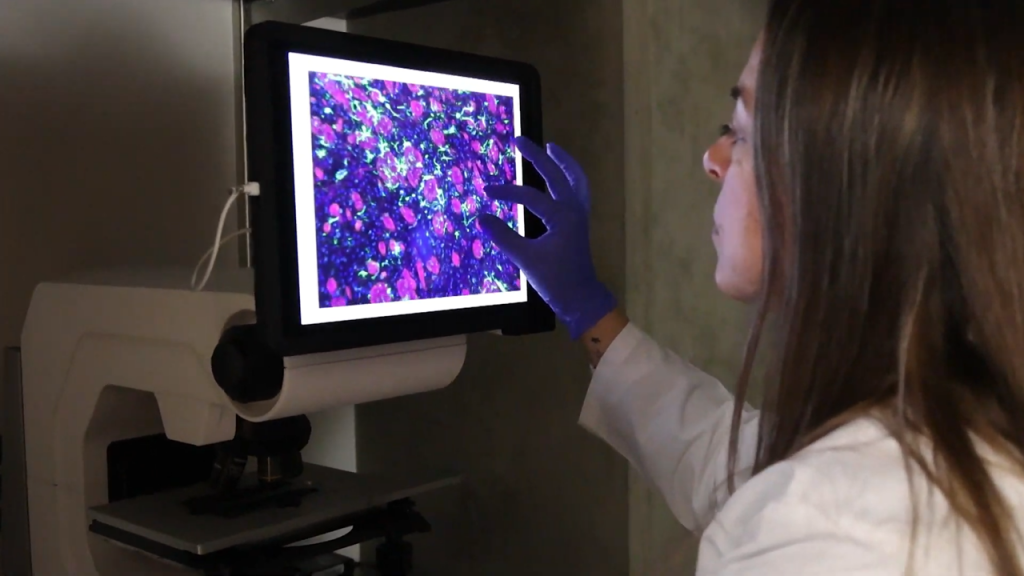

Explore careers in neuroscience

Rocio recommends getting involved in research early, such as through college labs or summer programmes. Rocio and her colleague in the Department of Neuroscience, Dr Marija Cvetanovic, founded the Go4Brains Program at the University of Minnesota, a week-long summer neuroscience programme for students who have historically faced challenges in accessing science and medicine opportunities. Go4Brains offers hands-on experiences, mentorship and exposure to cutting-edge research.

Rocio also suggests joining professional societies such as the Society for Neuroscience and the International Brain Research Organization to access networking opportunities, seminars and career resources.

Indeed outlines key information about careers in neuroscience.

Meet Rocio

My family owned a restaurant in Spain, but my upbringing was humble. Overcoming the distance, cultural differences, and challenges of being a first-generation scientist and, then, professor in the US has been deeply rewarding.

I became a neuroscientist almost by accident. I originally studied molecular biology and genetics, but I had always been fascinated by the brain and how it works. I became a Neuroscience Scholar at Duke University to connect this curiosity with real-world problems. There, I met inspiring scientists who worked directly with patients affected by Huntington’s disease and other movement disorders, which showed me that my research could improve lives.

A pivotal moment for me came when I began working with both research scientists and clinicians. Being able to obtain human samples and validate my observations of cell and mouse models of HD was truly a Eureka moment. It made me feel that my research was directly contributing to progress in understanding and addressing the disease.

Running a lab and conducting research can be demanding. I try to stay organised and prioritise tasks while remaining flexible for when unexpected challenges arise. I rely on my team, colleagues and students to collaborate, share ideas and tackle problems together. I also remind myself that setbacks are a natural part of research, and that each challenge is an opportunity to learn and improve. Finally, I make time for family, hobbies and physical activity, which help me maintain perspective and energy.

I am proud to know that my work and mentorship is inspiring younger generations. As a first-generation scientist, I understand how challenging it can be for many people to access opportunities in science. It’s highly rewarding to see students go on to pursue careers in science and know that I can have a lasting impact on the next wave of neuroscientists.

My ultimate goal is to continue until patients with HD have ways to live healthier and more fulfilling lives. I also hope to expand our knowledge into the broader field of neuroscience, particularly by exploring how synaptic regulation influences cognitive processes. And I aim to continue mentoring the next generation of scientists, helping them grow and make their own impact.

Rocio’s top tips

1. Stay curious, ask ‘why?’ and dive into hands-on research wherever you can.

2. Don’t be shy about reaching out to mentors – they love to share their experience.

3. Embrace challenges and learn from mistakes. They’re part of the discovery process.

4. Neuroscience is a huge, exciting playground. Bring your own unique perspective and creativity – it might just lead to the next big breakthrough.

Do you have a question for Rocio?

Write it in the comments box below and they will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

Read about research in behavioural neuroscience:

futurumcareers.com/what-increases-someones-risk-of-developing-addiction

0 Comments