The power of human rights in the modern world

Professor Todd Landman, a political scientist at the University of Nottingham in the UK, is devoted to promoting and preserving human rights in order to end modern slavery

TALK LIKE A POLITICAL SCIENTIST

DEMOCRACY – a type of government where the people living in a country can vote to choose the way the country is run

EXPLOITATION – treating people unfairly in order to benefit from the work they do. For example, people may be forced to work against their will (forced labour) or forced to work to pay off an unfair debt (bonded labour)

HUMAN RIGHTS – principles that protect all humans by promoting equality and freedom

MODERN SLAVERY – the recruitment of people for the purpose of different forms of exploitation

POLITICAL SCIENTIST – a researcher who analyses political activities and behaviour such as government policy and international agreements

RIGHTS PROTECTIVE COUNTRIES – countries that protect and enforce human rights through law

“Human rights are a celebration of human dignity,” says Professor Todd Landman, a political scientist at the University of Nottingham. These rights are our rights. A set of protective principles that provide a framework for laws around the world, allowing us all to live our lives free from fear, exploitation and oppression.

The concept of human rights is hundreds of years old, but the official ‘human rights’ were established in 1948 under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. These rights were developed through discussion and agreement between individual countries and the United Nations, and they shape both national and international laws.

Today, there are more than 60 recognised human rights, across categories such as civil and political rights, economic rights and social and cultural rights. As threats to the planet and environment continue to grow, there is also an emerging demand for environmental rights.

WHY DO HUMAN RIGHTS MATTER TO ALL OF US?

Human rights allow us to have freedom of religion, belief and thought, free expression and speech, and the freedom to form groups such as political parties and trade unions. They provide us with the right to a fair trial and protect us from torture or inhumane treatment. We are all entitled to fair working conditions, education and healthcare thanks to our human rights, and they protect us against unnecessary interference into our private lives.

“Human rights recognise our inherent dignity by virtue of being human, which includes the rights of refugees, migrants, asylum seekers, and stateless peoples,” says Todd. “Wrapped around the rights themselves is the principle of non-discrimination in our exercise and enjoyment of our human rights.”

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN HUMAN RIGHTS ARE ABUSED?

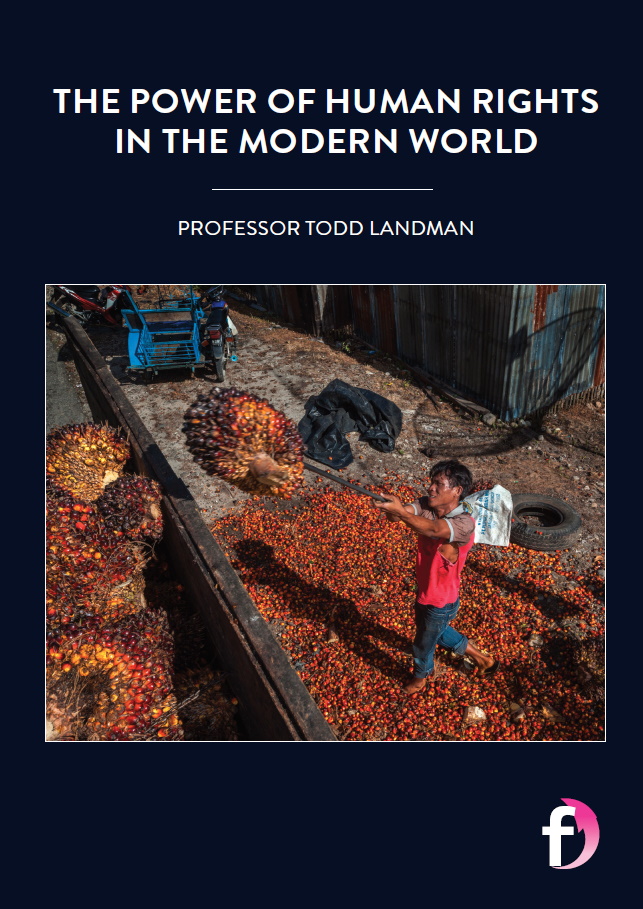

Common examples of human rights violations include unfair treatment of people accused of crime, forced labour and mistreatment of migrants. Preventing access to education or adequate healthcare also constitutes a violation of human rights. Many people around the world live and work in conditions that do not allow them to enjoy their human rights, and we need to realise that global supply chains often hide issues of human rights abuse within them. “Do you know where your mobile phone was produced?” asks Todd. “Do you know what conditions each component was produced in?”

“The most common portrayal of human rights is that they are rights for criminals, immigrants, refugees and other ‘unwanted people’,” explains Todd. Often, people don’t appreciate the everyday freedoms that human rights provide. In rights-protective countries we are all allowed to have individual beliefs without the fear of a ‘knock at the door’ from the authorities. “Human rights should be seen as basic protections for human flourishing,” adds Todd.

HOW DOES TODD STUDY HUMAN RIGHTS?

Todd’s research is based on the application of human rights in different countries around the world. He generates large datasets, collating decades’ worth of information about treaties and measurements of human rights in different countries. He then uses statistical analyses to establish relationships between human rights and other variables, such as the level of democracy, economic development or the presence of violent conflict. His current research applies this quantitative analysis to data on modern slavery.

Todd also conducts qualitative research, comparing different countries to help understand historical processes of human rights advance and the political processes involved in bringing about better protection of human rights.

Human rights research is a highly interdisciplinary field, addressing many different issues affecting people in the world. “My research involves a combination of international law, international relations, political science, economics and geography,” says Todd. His current research on modern slavery uses geospatial analysis and satellite images to understand which places across the world have a high probability of forced labour taking place.

WHAT IS MODERN SLAVERY?

Modern slavery is a term that covers a variety of practices, including forced labour, sexual exploitation, bonded labour, human trafficking and other forms of exploitation. “The most recent estimate of modern slavery is that there are 40.3 million people enslaved around the world, and no country is free of slavery,” says Todd. Complex individual, community and national factors make people vulnerable to becoming enslaved. According to a recent report from the Council of Foreign Relations, human trafficking alone is worth over 150 billion dollars a year to perpetrators.

WHAT HAS TODD LEARNT ABOUT MODERN SLAVERY?

There is still work to do on defining modern slavery. Todd analyses the relationship between globalisation and modern slavery and assesses the effectiveness of measures to end the practice. His work on forced labour in the brick kiln industry in South Asia is examining geographical factors that increase the prevalence of modern slavery and he is investigating its impact on environmental degradation.

Todd’s recent findings suggest that globalisation is not related to high levels of slavery and that international trade affects modern slavery in developing countries. It is also difficult to monitor and evaluate organisations that aim to help survivors of modern slavery, due to the way their programmes of intervention are set up. Todd has demonstrated that extending support for survivors of modern slavery in the UK will provide benefits that greatly outweigh the costs to the government.

CAN POLITICAL SCIENCE AND HUMAN RIGHTS HELP TO END MODERN SLAVERY?

Political scientists and human rights researchers like Todd try to understand the nature and extent of modern slavery. Statistical analyses of their data can help to explain the variation in the prevalence of modern slavery around the world. And their results can be used to advise governments and organisations on how best to end modern slavery. The United Nations have a goal to end modern slavery by 2030. “I hope that my work helps to reach this goal,” says Todd.

PROFESSOR TODD LANDMAN

PROFESSOR TODD LANDMAN

University of Nottingham, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Political Science, Human Rights

RESEARCH PROJECT: Investigating modern slavery from a human rights perspective to understand the nature of the problem and develop interventions that will help to end the practice

FUNDERS: Economic and Social Research Council, International Justice Mission, Global Research Challenge Fund, Nuffield Foundation, US Trafficking in Persons Office

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM163

Asylum Steampunk Festival, Lincoln, 2016.

DEMOCRACY – a type of government where the people living in a country can vote to choose the way the country is run

EXPLOITATION – treating people unfairly in order to benefit from the work they do. For example, people may be forced to work against their will (forced labour) or forced to work to pay off an unfair debt (bonded labour)

HUMAN RIGHTS – principles that protect all humans by promoting equality and freedom

MODERN SLAVERY – the recruitment of people for the purpose of different forms of exploitation

POLITICAL SCIENTIST – a researcher who analyses political activities and behaviour such as government policy and international agreements

RIGHTS PROTECTIVE COUNTRIES – countries that protect and enforce human rights through law

“Human rights are a celebration of human dignity,” says Professor Todd Landman, a political scientist at the University of Nottingham. These rights are our rights. A set of protective principles that provide a framework for laws around the world, allowing us all to live our lives free from fear, exploitation and oppression.

The concept of human rights is hundreds of years old, but the official ‘human rights’ were established in 1948 under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. These rights were developed through discussion and agreement between individual countries and the United Nations, and they shape both national and international laws.

Today, there are more than 60 recognised human rights, across categories such as civil and political rights, economic rights and social and cultural rights. As threats to the planet and environment continue to grow, there is also an emerging demand for environmental rights.

WHY DO HUMAN RIGHTS MATTER TO ALL OF US?

Human rights allow us to have freedom of religion, belief and thought, free expression and speech, and the freedom to form groups such as political parties and trade unions. They provide us with the right to a fair trial and protect us from torture or inhumane treatment. We are all entitled to fair working conditions, education and healthcare thanks to our human rights, and they protect us against unnecessary interference into our private lives.

“Human rights recognise our inherent dignity by virtue of being human, which includes the rights of refugees, migrants, asylum seekers, and stateless peoples,” says Todd. “Wrapped around the rights themselves is the principle of non-discrimination in our exercise and enjoyment of our human rights.”

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN HUMAN RIGHTS ARE ABUSED?

Common examples of human rights violations include unfair treatment of people accused of crime, forced labour and mistreatment of migrants. Preventing access to education or adequate healthcare also constitutes a violation of human rights. Many people around the world live and work in conditions that do not allow them to enjoy their human rights, and we need to realise that global supply chains often hide issues of human rights abuse within them. “Do you know where your mobile phone was produced?” asks Todd. “Do you know what conditions each component was produced in?”

“The most common portrayal of human rights is that they are rights for criminals, immigrants, refugees and other ‘unwanted people’,” explains Todd. Often, people don’t appreciate the everyday freedoms that human rights provide. In rights-protective countries we are all allowed to have individual beliefs without the fear of a ‘knock at the door’ from the authorities. “Human rights should be seen as basic protections for human flourishing,” adds Todd.

HOW DOES TODD STUDY HUMAN RIGHTS?

Todd’s research is based on the application of human rights in different countries around the world. He generates large datasets, collating decades’ worth of information about treaties and measurements of human rights in different countries. He then uses statistical analyses to establish relationships between human rights and other variables, such as the level of democracy, economic development or the presence of violent conflict. His current research applies this quantitative analysis to data on modern slavery.

Todd also conducts qualitative research, comparing different countries to help understand historical processes of human rights advance and the political processes involved in bringing about better protection of human rights.

Human rights research is a highly interdisciplinary field, addressing many different issues affecting people in the world. “My research involves a combination of international law, international relations, political science, economics and geography,” says Todd. His current research on modern slavery uses geospatial analysis and satellite images to understand which places across the world have a high probability of forced labour taking place.

WHAT IS MODERN SLAVERY?

Modern slavery is a term that covers a variety of practices, including forced labour, sexual exploitation, bonded labour, human trafficking and other forms of exploitation. “The most recent estimate of modern slavery is that there are 40.3 million people enslaved around the world, and no country is free of slavery,” says Todd. Complex individual, community and national factors make people vulnerable to becoming enslaved. According to a recent report from the Council of Foreign Relations, human trafficking alone is worth over 150 billion dollars a year to perpetrators.

WHAT HAS TODD LEARNT ABOUT MODERN SLAVERY?

There is still work to do on defining modern slavery. Todd analyses the relationship between globalisation and modern slavery and assesses the effectiveness of measures to end the practice. His work on forced labour in the brick kiln industry in South Asia is examining geographical factors that increase the prevalence of modern slavery and he is investigating its impact on environmental degradation.

Todd’s recent findings suggest that globalisation is not related to high levels of slavery and that international trade affects modern slavery in developing countries. It is also difficult to monitor and evaluate organisations that aim to help survivors of modern slavery, due to the way their programmes of intervention are set up. Todd has demonstrated that extending support for survivors of modern slavery in the UK will provide benefits that greatly outweigh the costs to the government.

CAN POLITICAL SCIENCE AND HUMAN RIGHTS HELP TO END MODERN SLAVERY?

Political scientists and human rights researchers like Todd try to understand the nature and extent of modern slavery. Statistical analyses of their data can help to explain the variation in the prevalence of modern slavery around the world. And their results can be used to advise governments and organisations on how best to end modern slavery. The United Nations have a goal to end modern slavery by 2030. “I hope that my work helps to reach this goal,” says Todd.

PROFESSOR TODD LANDMAN

PROFESSOR TODD LANDMAN

University of Nottingham, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Political Science, Human Rights

RESEARCH PROJECT: Investigating modern slavery from a human rights perspective to understand the nature of the problem and develop interventions that will help to end the practice

FUNDERS: Economic and Social Research Council, International Justice Mission, Global Research Challenge Fund, Nuffield Foundation, US Trafficking in Persons Office

ABOUT POLITICAL SCIENCE

Political science is a branch of social science that involves the scientific study of politics. This includes analysis of political activities and behaviour as well as laws and international agreements.

WHAT IS REWARDING ABOUT RESEARCH IN POLITICAL SCIENCE?

“Political science focuses on real world problems and global challenges,” says Todd. These are complex issues affected by a vast range of factors from political power and economic structures to geographical distributions of raw resources. Political scientists study these issues to help build a better, fairer future. Todd enjoys designing and conducting his research projects, as well as travelling the world to work with international organisations and foreign ministries, and teaching students to challenge ideas about politics and power.

WHAT ISSUES FACE THE NEXT GENERATION OF POLITICAL SCIENTISTS?

Todd explains that the current key issues in political science are, “the deterioration of democracy, the rise of nationalism and populism, the ever-present threats of conflict, war, and terrorism, and environmental degradation and climate change.” The consequences of these will need to be addressed by the next generation of political scientists. “Human rights run right through each of these main issues, but in different ways,” explains Todd, “which will require the continued focus on asking the right questions to address the issues.”

WHAT SKILLS WOULD YOU GAIN FROM STUDYING POLITICAL SCIENCE AND HUMAN RIGHTS?

Political scientists develop analytical skills, the ability to understand political concepts and the ability to communicate complex issues in an understandable way. Political scientists travel the world and learn to relate to and appreciate people from all over the world with a wide range of beliefs and opinions. “Human rights have given me a moral compass to approach the world,” says Todd, “grounded in what ought and what ought not be in place to maximise human flourishing and human dignity.”

EXPLORE A CAREER IN HUMAN RIGHTS

• Human rights expertise is needed in many areas of life. You could work in law, politics, business, charities, international organisations, creative arts, advocacy, data analysis…

• Listen to Todd’s podcast ‘The Rights Track’ to gain an understanding of human rights issues (www.rightstrack.org).

• The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (www.ohchr.org), Amnesty International (www.amnesty.org.uk) and Citizens UK (www.citizensuk.org) all provide opportunities to get involved with the promotion of human rights.

• Todd and his colleagues give talks to schools near the University of Nottingham. Take a look at your local university’s website to find out if their Social Science faculty provides outreach opportunities.

• According to Glassdoor, the average salary for people working in the field of human rights is £35,600.

• “Study history, science, maths, philosophy, law, politics and economics to get a grounding in how the world works and moves through time,” says Todd. “Acquire digital skills (data management and visualisation), logical reasoning and an ability to read complex text fluidly.”

• Most universities will offer a degree in politics, political science or international relations

HOW DID TODD BECOME A POLITICAL SCIENTIST?

WHAT WERE YOUR INTERESTS WHEN YOU WERE YOUNGER?

I grew up on a farm in rural Pennsylvania. I was an avid reader (especially of Sherlock Holmes and Alfred Hitchcock), a keen swimmer, sailor, skater, trombone player and magician.

HAVE YOU ALWAYS BEEN INTERESTED IN POLITICS AND HUMAN RIGHTS?

I did my first degree in political science at the University of Pennsylvania where I studied Latin American languages, history and politics. During this time (the 1980s), Latin America was undergoing profound transformations, experiencing military rule, civil war and transitioning to democracy. I then completed a master’s degree in Latin American studies, and these studies forged an interest in democracy and human rights in the region. My interest became more global as I progressed, completing a master’s and PhD in political science.

WHAT INSPIRED YOU TO WORK IN THE FIELD OF HUMAN RIGHTS?

While I was a student, I was asked to develop crime scene photographs from the site where a group of Jesuit priests and their maid had been murdered in El Salvador in 1989. Seeing the images come to life motivated me to study human rights and commit myself to their advancement.

WHAT ARE YOUR AMBITIONS FOR THE FUTURE OF YOUR WORK?

My ambitions include academic leadership, research and publication, and continued engagement with the international human rights community with a particular focus on ending modern slavery.

AS WELL AS BEING A PROFESSOR OF POLITICAL SCIENCE, YOU ARE ALSO A PROFESSIONAL MAGICIAN! CAN YOU TELL US ABOUT THIS?

I started magic when I was 8 years old thanks to a school friend. I was mentored by a local magician and took part in magic conferences. I performed throughout school and university, and continued to perform when I moved to the UK in 1993, founding the British Society of Mystery Entertainers in 2007. I am also a Visiting Professor of Performance Magic at the University of Huddersfield, where I perform and run workshops for drama students. I love performing live shows and I enjoy creating my own effects and routines and collaborating with magicians around the world.

YOU CALL YOUR WORK ‘ACADEMIC MAGIC’. WHAT IS THIS?

Over the years, my magic has evolved from close up performances to narrative-based magic, communicating big ideas from many different academic disciplines. I brought my academic work on politics and human rights together with my magic to create the performance persona of The Academic Magician. My shows are crafted to educate, entertain, and baffle all at the same time. Topics in my performances range from the separation of mind and body to an exploration of social justice through a famous mental asylum in Middlesex. I have my own Magiculum, a physical space with a collection of magical objects and books where likeminded magicians can meet and publish essays on the meaning of magic.

TODD’S TOP TIPS

01 Keep an open mind about the opportunities available to you. The world is constantly changing so be ready to adapt and have the creativity to solve problems.

02 Follow your passions outside of work and education. You will gain unique skills through sport, music, art, volunteering and any other hobbies.

03 Take time out from the daily grind. Reading, reflecting and being mindful are great ways to do this. You will work better when you are refreshed.

Do you have a question for Todd?

Write it in the comments box below and Todd will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)