The premenstrual defence

Dr Caroline Henaghan, based at the University of Manchester in the UK, is taking a socio-legal and interdisciplinary approach to the problems associated with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. The findings will help develop understanding of – and appreciation for – the relationship between the female menstrual cycle and mental health

GLOSSARY

APPELLANT – a person appealing against a court’s decision

AUTOMATISM – a defence which holds that a person cannot be considered as responsible for their actions

DEFENDANT – the accused person in a court of law

DEFENCE – the response given by the defendant to excuse or justify their criminal actions

DIMINISHED RESPONSIBILITY – when a defendant cannot be seen as fully responsible for their actions because of the impact a recognised medical condition has on their mental capacity

EXPERT WITNESS – a person with expert knowledge or skills in particular field who testifies in court

INSANITY – when a defendant is considered unable to understand their actions

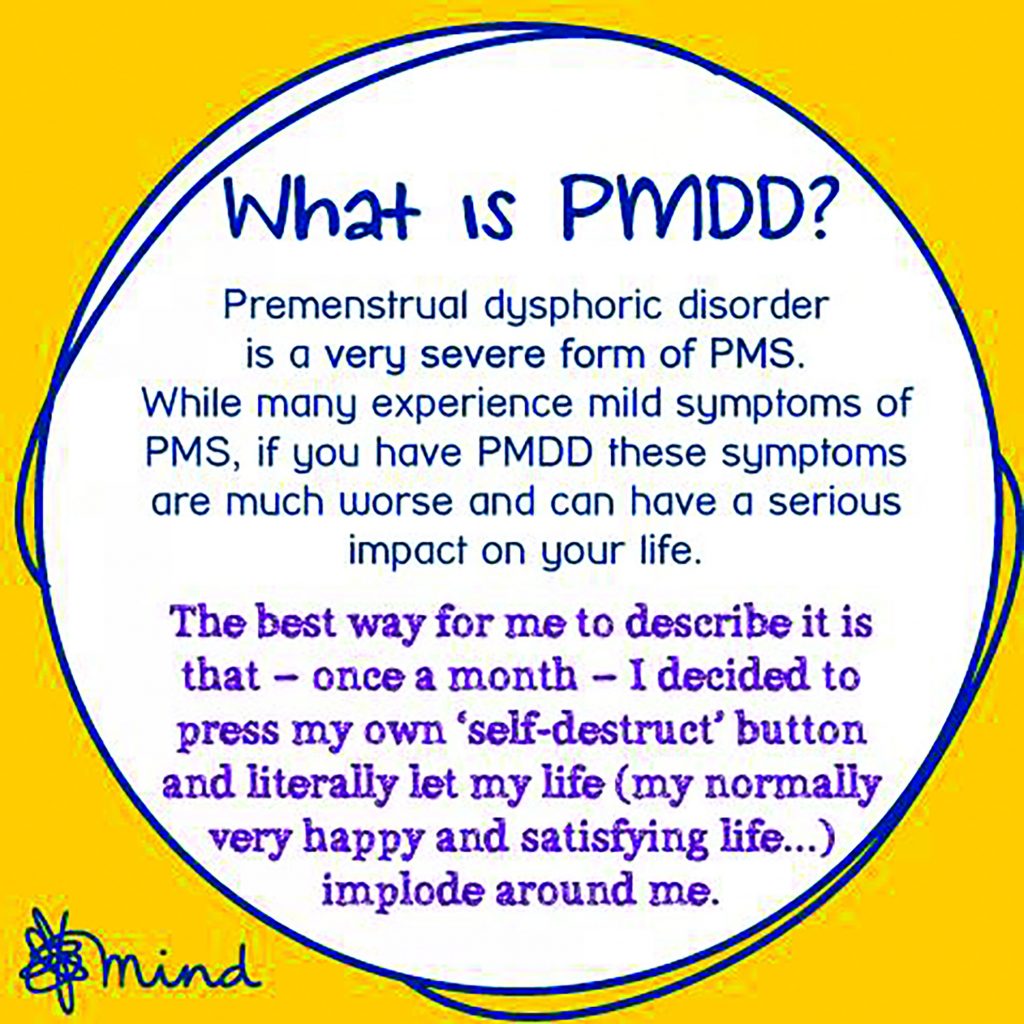

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is a health problem that is often compared to premenstrual syndrome (PMS) but is more serious. The condition typically occurs in women in the week or two before their period starts when hormone levels start to fall after ovulation. PMDD can cause a wide range of symptoms, ranging from severe depression to irritability and anxiety.

Dr Caroline Henaghan, who is based at the University of Manchester in the UK, had PMDD for several years before she realised that her problems with anxiety and depression were connected to her menstrual cycle. After conducting her own research into PMDD and PMS, she found out about a doctor called Katherina Dalton who, alongside another clinician called Raymond Greene, had originally coined the term premenstrual syndrome (what we now know as PMS) in 1953.

However, as a lawyer, what most interested Caroline was that Katherina had appeared as an expert witness in a number of murder trials in the 1980s, where she had given evidence that allowed three different female defendants to plead a defence of diminished responsibility on account of their PMS symptoms. This is what led to Caroline’s ongoing interest in ‘the premenstrual defence’ which forms the basis of her current research.

PMDD – A MEDICAL DISORDER

Somewhat remarkably, it was not until 2013 that PMDD was listed as a mental health problem. On the other hand, there is a long history of society and culture attaching prejudice, stigma and shame to the female menstrual cycle. Consider the fact that it was only in 2021 that the ‘tampon tax’ was abolished – before then, menstrual products were considered luxury items and were taxed as such! We often consider that we live in a civilised society, but when faced with the idea that tampons are luxury items, it is easy to see how far we still have to go. However, the abolition of the tax shows that we are headed in the right direction, albeit slowly.

THE LEGAL POSITION OF THE PREMENSTRUAL DEFENDANT

The key idea behind the premenstrual defence is that a woman’s behaviours, moods and actions can be driven by PMDD and, therefore, a greater degree of understanding of this should be shown when the woman is charged or sentenced. However, as it stands, there is no such thing as a premenstrual defence. “A defendant who seeks to rely on their premenstrual symptoms to defend themselves from a criminal charge is still subject to the same laws and defence rules as any other person,” explains Caroline. “Interestingly though, in the 1982 case of R v Smith [1982] CLR 531, which was heard in the English Court of Appeal, the appellant Sandie Smith ‘invited the court to declare that a special defence was available to a woman suffering from premenstrual tension if the jury decided on the evidence that she was morally blameless’. But this argument was rejected by the court.”

This means that the present-day premenstrual defendant must rely on existing defences such as insanity, automatism or diminished responsibility. Generally speaking, there is no effective and proportionate defence for somebody in her situation – and often this is also the case for lots of other defendants who commit a crime whilst suffering from a mental health disorder. In which case, a defendant has no option but to plead guilty to a criminal offence and then rely on the judge being merciful towards her when it comes to her plea in mitigation and sentencing.

CAROLINE’S RESEARCH

Ultimately, Caroline wants to change the story that surrounds premenstrual disorders. Her background as a qualified lawyer provides the ideal springboard for her to examine PMDD through the lens of criminal responsibility. She has gone on to undertake a post-doctoral position, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council. “This has afforded me the opportunity to broaden the scope of my sociolegal research questions and look at other issues relating to the problem of the premenstrual disorders, including the social role of medicine and science, and the complexities of feminist agendas in this area of study,” says Caroline. “In turn, that’s meant that, this year, I have been able to get involved in wider policy initiatives, such as the UK government’s call for evidence for its new Women’s Health Strategy.”

Caroline’s hope is that her research-based contributions toward a new set of healthcare policies for women will lead to greater awareness of PMDD and help to strength the female patient ‘voice’ within the UK healthcare system. For Caroline, this is one of the most positive aspects of any research journey – building on what you have already learned and discovering new and exciting directions for your research.

COLLABORATIONS

One of the most important aspects of Caroline’s project is the interdisciplinary approach it takes – something that is made possible by the involvement of many experts from different fields, including doctrinal and sociolegal academics, medical specialists including gynaecologists, scientific researchers including clinical psychologists, medical historians and archivists, feminist activists, and creative practitioners working in the arts. “My research is really interdisciplinary, and I think that is because much of what I do focuses on the individual who is at the centre of the project – the premenstrual defendant or the person suffering from a premenstrual disorder,” explains Caroline. “I have reflected on this before and asked myself if it is a good thing to always be drawing on a such a wide range of topic-areas. But in recent years there has been a strong shift towards interdisciplinarity within research across a number of different fields and I think that research institutions are seeing the benefits of having an interdisciplinary research team working on a particular project.”

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM224

APPELLANT – a person appealing against a court’s decision

AUTOMATISM – a defence which holds that a person cannot be considered as responsible for their actions

DEFENDANT – the accused person in a court of law

DEFENCE – the response given by the defendant to excuse or justify their criminal actions

DIMINISHED RESPONSIBILITY – when a defendant cannot be seen as fully responsible for their actions because of the impact a recognised medical condition has on their mental capacity

EXPERT WITNESS – a person with expert knowledge or skills in particular field who testifies in court

INSANITY – when a defendant is considered unable to understand their actions

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is a health problem that is often compared to premenstrual syndrome (PMS) but is more serious. The condition typically occurs in women in the week or two before their period starts when hormone levels start to fall after ovulation. PMDD can cause a wide range of symptoms, ranging from severe depression to irritability and anxiety.

Dr Caroline Henaghan, who is based at the University of Manchester in the UK, had PMDD for several years before she realised that her problems with anxiety and depression were connected to her menstrual cycle. After conducting her own research into PMDD and PMS, she found out about a doctor called Katherina Dalton who, alongside another clinician called Raymond Greene, had originally coined the term premenstrual syndrome (what we now know as PMS) in 1953.

However, as a lawyer, what most interested Caroline was that Katherina had appeared as an expert witness in a number of murder trials in the 1980s, where she had given evidence that allowed three different female defendants to plead a defence of diminished responsibility on account of their PMS symptoms. This is what led to Caroline’s ongoing interest in ‘the premenstrual defence’ which forms the basis of her current research.

PMDD – A MEDICAL DISORDER

Somewhat remarkably, it was not until 2013 that PMDD was listed as a mental health problem. On the other hand, there is a long history of society and culture attaching prejudice, stigma and shame to the female menstrual cycle. Consider the fact that it was only in 2021 that the ‘tampon tax’ was abolished – before then, menstrual products were considered luxury items and were taxed as such! We often consider that we live in a civilised society, but when faced with the idea that tampons are luxury items, it is easy to see how far we still have to go. However, the abolition of the tax shows that we are headed in the right direction, albeit slowly.

THE LEGAL POSITION OF THE PREMENSTRUAL DEFENDANT

The key idea behind the premenstrual defence is that a woman’s behaviours, moods and actions can be driven by PMDD and, therefore, a greater degree of understanding of this should be shown when the woman is charged or sentenced. However, as it stands, there is no such thing as a premenstrual defence. “A defendant who seeks to rely on their premenstrual symptoms to defend themselves from a criminal charge is still subject to the same laws and defence rules as any other person,” explains Caroline. “Interestingly though, in the 1982 case of R v Smith [1982] CLR 531, which was heard in the English Court of Appeal, the appellant Sandie Smith ‘invited the court to declare that a special defence was available to a woman suffering from premenstrual tension if the jury decided on the evidence that she was morally blameless’. But this argument was rejected by the court.”

This means that the present-day premenstrual defendant must rely on existing defences such as insanity, automatism or diminished responsibility. Generally speaking, there is no effective and proportionate defence for somebody in her situation – and often this is also the case for lots of other defendants who commit a crime whilst suffering from a mental health disorder. In which case, a defendant has no option but to plead guilty to a criminal offence and then rely on the judge being merciful towards her when it comes to her plea in mitigation and sentencing.

CAROLINE’S RESEARCH

Ultimately, Caroline wants to change the story that surrounds premenstrual disorders. Her background as a qualified lawyer provides the ideal springboard for her to examine PMDD through the lens of criminal responsibility. She has gone on to undertake a post-doctoral position, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council. “This has afforded me the opportunity to broaden the scope of my sociolegal research questions and look at other issues relating to the problem of the premenstrual disorders, including the social role of medicine and science, and the complexities of feminist agendas in this area of study,” says Caroline. “In turn, that’s meant that, this year, I have been able to get involved in wider policy initiatives, such as the UK government’s call for evidence for its new Women’s Health Strategy.”

Caroline’s hope is that her research-based contributions toward a new set of healthcare policies for women will lead to greater awareness of PMDD and help to strength the female patient ‘voice’ within the UK healthcare system. For Caroline, this is one of the most positive aspects of any research journey – building on what you have already learned and discovering new and exciting directions for your research.

COLLABORATIONS

One of the most important aspects of Caroline’s project is the interdisciplinary approach it takes – something that is made possible by the involvement of many experts from different fields, including doctrinal and sociolegal academics, medical specialists including gynaecologists, scientific researchers including clinical psychologists, medical historians and archivists, feminist activists, and creative practitioners working in the arts. “My research is really interdisciplinary, and I think that is because much of what I do focuses on the individual who is at the centre of the project – the premenstrual defendant or the person suffering from a premenstrual disorder,” explains Caroline. “I have reflected on this before and asked myself if it is a good thing to always be drawing on a such a wide range of topic-areas. But in recent years there has been a strong shift towards interdisciplinarity within research across a number of different fields and I think that research institutions are seeing the benefits of having an interdisciplinary research team working on a particular project.”

IMPACT

There is the possibility that the research could impact on criminal law – there are already moves to bring in a defence of ‘not guilty by reason of recognised medical condition’. Caroline’s research proposes that this should be further extended to ensure that as many defendants as possible can have their mental health disorders taken into account when it comes to questions about their criminal responsibility. “Because of my lived experience of PMDD, I try to publish my research in lots of different formats so that it reaches as wide an audience as possible – and that includes other premenstrual patients,” says Caroline. “That way, they will know that research is being undertaken to try and improve their situation and they will know that their voices are being represented when it comes to their experiences with PMDD. I think that is a really important way for me to make a meaningful impact with my research.”

This year, Caroline has done some part-time historical research at the John Rylands Research Institute and Library. It is a completely new direction for her and shows the breadth of possibility in a socio-legal career. The world is her oyster at present – so whether she becomes a lecturer and works in a law school teaching undergraduate students, or continues on her academic research path, she is bound to continue to make a positive impact on people’s lives.

DR CAROLINE HENAGHAN

DR CAROLINE HENAGHAN

School of Social Sciences (Law), The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Law

RESEARCH PROJECT: Adopting a socio-legal and interdisciplinary approach to overcoming the challenges associated with premenstrual dysphoric disorder and conceptualising a premenstrual defendant’s criminal responsibility

FUNDER: ESRC – North West Social Science Doctoral Training Partnership Postdoctoral Fellowship Scheme 2020/21.

DR CAROLINE HENAGHAN

DR CAROLINE HENAGHAN

School of Social Sciences (Law), The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Law

RESEARCH PROJECT: Adopting a socio-legal and interdisciplinary approach to overcoming the challenges associated with premenstrual dysphoric disorder and conceptualising a premenstrual defendant’s criminal responsibility

FUNDER: ESRC – North West Social Science Doctoral Training Partnership Postdoctoral Fellowship Scheme 2020/21.

ABOUT LAW

As Caroline’s career has shown, a law degree does not necessarily have to lead to becoming a barrister or solicitor. Caroline’s background as a qualified lawyer has stood her in good stead and informed her current research, but having an interest in the social aspects of the law – and, in this case, the position of women in society – are equally important.

WHAT DOES CAROLINE FIND REWARDING ABOUT RESEARCH IN HER FIELD?

Caroline is quick to point to her love of the ‘social’ aspect of her socio-legal research. “The bits of what I am doing that I know have the potential to exert a powerful impact on people’s lives are the best. For example, making a contribution to re-thinking the current English criminal law defences, which have been in existence for years and years,” says Caroline.

“Although my research might only play a small part in any change that does come about, it is rewarding to know that I’ve been involved in that reform. Just as it is rewarding to have the opportunity to be involved in this project and tell everybody a bit more about my research!”

WHAT ISSUES WILL FACE THE NEXT GENERATION OF LAW ACADEMICS?

Caroline thinks that law academics will need to address very similar issues to other academics. In a post-covid world, where technological advances and ways of working are changing all the time, a period of adjustment is going to be necessary. “Law is still viewed as a traditional subject, so there is certainly lots of scope for advancement, change and new ways of thinking,” explains Caroline. “I think that will probably come to fruition for the next generation of law academics – so the traditional law school that we have all come to know might be a very different place in years to come.”

EXPLORE CAREERS IN LAW

• If you want to train as a barrister as Caroline did, you should visit the Bar Council website, particularly the ‘becoming a barrister’ section.

• Alternatively, if you are aiming to become a solicitor, you should take a look at the Law Society website and the ‘becoming a solicitor’ section.

• Technically, there is no official minimum salary for trainee lawyers, however The Law Society recommends a minimum of £22,794 for those training in London and £20,217 for trainees elsewhere in the country. You can earn substantially more once you are qualified and more experienced.

PATHWAY FROM SCHOOL TO LAW

Caroline says that there are no specific requirements to study a particular subject at school or college in order to go on and study law at university. This is good news because it means you can concentrate on studying what you love! “If you have a choice, then my advice would be to study a subject that you enjoy – that way, you are more likely to do well in it, fingers crossed!” says Caroline. “However, there are specific rules around how you then go on to qualify as a lawyer, so you do need to make sure you understand the best route for you to take at that stage.”

Prospects says: “Becoming a lawyer via the university route requires you to complete a qualifying law degree (LLB) before taking the Solicitors Qualifying Examination (SQE), which is set to replace the Graduate Diploma in Law (GDL) and Legal Practice Course (LPC) for all new entrants in September 2021, although there are transitional arrangements in place for those already studying these courses.”

HOW DID CAROLINE BECOME A LAW RESEARCHER?

WHAT WERE YOUR INTERESTS WHEN YOU WERE GROWING UP?

Reading! I am an only child and I’m afraid that I’m also a bit of cliché. My head was always in a book when I was growing up, so nothing much has changed there!

WHO OR WHAT INSPIRED YOU TO PURSUE LAW?

My dad – but he was a carpenter, not a lawyer. One day, when I was eight years old, my dad was called up to do jury service. He came back and told me all about his experience of going to court. I was hooked and I haven’t looked back since. Along the way, I have met many others who have given me the inspiration to keep going. But that first spark of interest came from my dad’s stint as a member of a crown court jury.

WHAT ATTRIBUTES HAVE MADE YOU SUCCESSFUL IN YOUR CAREER?

Adaptability. Life can often be a series of lots of different challenges. But what is it they say? ‘Every problem is an opportunity in disguise’. I have had a few different roles in my career and, for me, being able to adapt has been key to my success in all the different things I’ve done. Something that I’ve learned more recently – just have a go! Whatever it is, even if I don’t think I stand a chance, I try to have a go. You never know your luck when you try something new. And if you’re not always successful in whatever it is you’re having a go at, it will still be a good learning curve in any event.

HOW DO YOU OVERCOME OBSTACLES AND SWITCH OFF FROM YOUR WORK?

Persistence is key to how I overcome any obstacles I might face. I don’t always get things right first time – nobody does! But if I keep reminding myself to keep on going, I’m bound to get there in the end. That’s my philosophy. And walking is the best way for me to get myself away from the screen and switch off from work. Doesn’t matter where I am – the rhythm of walking along helps me to slow down and unwind.

WHAT ARE YOUR PROUDEST CAREER ACHIEVEMENTS SO FAR?

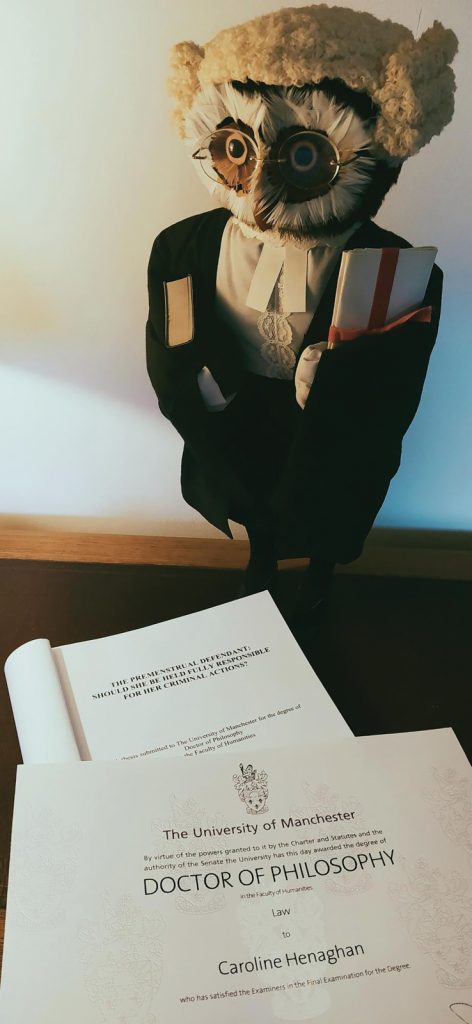

Finishing my PhD! That was the culmination of an awful lot of hard work (and obviously, it means that I now get to be called Dr Henaghan). But, also, because it marked the end of a long journey with my own PMDD. One year after I started the PhD, I underwent surgery for my condition. Without that operation, I am not sure that I would be in the position I am today, or that I would have been able to complete my PhD. That’s my proudest achievement so far. Hopefully, there will be more to come…

01 Find out what you enjoy doing and try to build a career around the things you are really passionate about.

02 I know it is a cliché, but if at first you don’t succeed then try and try again – so much of science is failing initially, but perseverance will get you to where you want to be.

03 Try and enjoy the ride. When times get tough (and they will), take a step back and think about why you began doing what you are doing. It will all be worth it in the end!

Do you have a question for Caroline?

Write it in the comments box below and Caroline will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

Hi William,

Thank you for your comment. We have passed this on the Caroline and trust she’ll be in contact directly.

Futurum Webmaster.

Caroline ,I’m seeking your help for my daughter…

Regards

Rosemary

Hi Rosemary,

We have passed your message on to Caroline and hope she reaches out to you.

Best wishes,

Futurum Webmaster

Please help me. I would appreciate it if Caroline would get in contact with me. I have a case that I feel she’d be interested in and her expertise and personal experiences would be of great value and importance to me.