“We need to radically reform the national curriculum, but that’s not going to happen overnight.”

According to recent research, 84% of young people all over the world are worried about the climate crisis. So why is climate education left solely to geography and science teachers? Former English teacher and founder of ThoughtBox Education, Rachel Musson, explains why she is working with organisations like Teach the Future to bring climate education into all subjects in the UK’s national curriculum

WHAT IS YOUR EXPERIENCE OF CLIMATE EDUCATION IN THE UK?

At the moment, students receive 13 hours of explicit climate education across the entire primary and secondary sphere. It’s taught in geography and science but lots of students aren’t taking geography at GCSE level, which means many are missing out. Crucially, we need to recognise that it’s not the geography or science teacher’s job to teach students about climate change. We should all be responsible because climate change impacts all of us.

A lot of the young people we work with find it incredibly confusing as to why they’re not learning anything about the climate crisis. Yet teachers of all subjects don’t have the headspace to bring it in. This is one of the biggest issues with climate education as it’s currently taught – it’s piecemeal and disconnected. What we need is an education for sustainability, happening right across the school context.

AS A FORMER SECONDARY ENGLISH TEACHER, HOW DID YOU BRING CLIMATE EDUCATION INTO YOUR LESSONS?

Outside the classroom, I set up an eco-group which enabled young people to start recycling schemes, community projects, meat free Mondays, swap shops and energy saving strategies.

In the classroom, I was fortunate that English lessons provided a discussion framework. You’re reading books and poems whilst discussing big human issues and ideas with students. English lessons can be an opportunity to talk about thoughts, feelings and questions around things that are happening in the text to explore how these thoughts, feelings and questions relate to the wider world. Learning to feel connected to ourselves, others and the wider world is a crucial part of this sort of learning.

Even though I was an English teacher, I was also involved in cross-cultural learning projects, connecting with people living in different, more sustainable cultures.

DID STUDENTS COME TO YOU TO TALK ABOUT CLIMATE CHANGE?

One of the reasons we started an environmental network in my last school was because I had several students who were aghast that nothing was being done. Through the eco-group, we set up eco-audits and all the measures I mentioned previously, which were a way for students to feel that they had something purposeful to do and were making a change.

According to recent research*, which asked 10,000 young people across 10 countries how they feel about climate change, 75% think the future is frightening, 84% are incredibly worried about the climate crisis, and 45% say it is already affecting their daily lives. These children aren’t necessarily living in the Maldives or on the frontline, but they’re aware of the climate crisis and they don’t know what to do.

WHAT IS YOUR EXPERIENCE OF CLIMATE EDUCATION IN THE UK?

At the moment, students receive 13 hours of explicit climate education across the entire primary and secondary sphere. It’s taught in geography and science but lots of students aren’t taking geography at GCSE level, which means many are missing out. Crucially, we need to recognise that it’s not the geography or science teacher’s job to teach students about climate change. We should all be responsible because climate change impacts all of us.

A lot of the young people we work with find it incredibly confusing as to why they’re not learning anything about the climate crisis. Yet teachers of all subjects don’t have the headspace to bring it in. This is one of the biggest issues with climate education as it’s currently taught – it’s piecemeal and disconnected. What we need is an education for sustainability, happening right across the school context.

AS A FORMER SECONDARY ENGLISH TEACHER, HOW DID YOU BRING CLIMATE EDUCATION INTO YOUR LESSONS?

Outside the classroom, I set up an eco-group which enabled young people to start recycling schemes, community projects, meat free Mondays, swap shops and energy saving strategies.

In the classroom, I was fortunate that English lessons provided a discussion framework. You’re reading books and poems whilst discussing big human issues and ideas with students. English lessons can be an opportunity to talk about thoughts, feelings and questions around things that are happening in the text to explore how these thoughts, feelings and questions relate to the wider world. Learning to feel connected to ourselves, others and the wider world is a crucial part of this sort of learning.

Even though I was an English teacher, I was also involved in cross-cultural learning projects, connecting with people living in different, more sustainable cultures.

DID STUDENTS COME TO YOU TO TALK ABOUT CLIMATE CHANGE?

One of the reasons we started an environmental network in my last school was because I had several students who were aghast that nothing was being done. Through the eco-group, we set up eco-audits and all the measures I mentioned previously, which were a way for students to feel that they had something purposeful to do and were making a change.

According to recent research*, which asked 10,000 young people across 10 countries how they feel about climate change, 75% think the future is frightening, 84% are incredibly worried about the climate crisis, and 45% say it is already affecting their daily lives. These children aren’t necessarily living in the Maldives or on the frontline, but they’re aware of the climate crisis and they don’t know what to do.

IS IT UP TO TEACHERS TO BRING CLIMATE EDUCATION INTO THEIR CLASSROOMS?

Teachers encounter so many challenges. There is a hugely dense curriculum in every subject that must be taught. So many teachers feel the pressure of having to get through so much content. It feels as if there is little time or space for reflection, never mind discussing something that’s happening outside of the learning space. It shouldn’t be up to teachers to find ways to bring climate education into the classroom but, unfortunately, that’s where we are at this point.

WHAT NEEDS TO HAPPEN AT A TOP-LEVEL RATHER THAN FROM BOTTOM-UP?

We need to radically reform the national curriculum, but that’s not going to happen overnight. It’s a huge beast. What we need in the interim is integration – connecting climate education with the curriculum all the way through the learning process. We need to embed the knowledge, skills and practices for thriving futures right across the curriculum.

Most importantly, climate education isn’t just about teaching information. It needs to be supported with strategies for growing emotional resilience. I work with the Climate Psychology Alliance who deal with climate anxiety and recognise the psychological reasons for not simply teaching children hugely horrifying facts about climate collapse.

There are two approaches that need to happen: Meeting where we are now by connecting to initiatives such as the Department for Education’s (DfE’s) new climate and sustainability framework, whilst recognising that, in the future, we really need to explore a new model for education. What we need is an education for sustainability (not just sustainability education).

ARE TEACHERS STARTING TO ADVANCE WITH CLIMATE EDUCATION THEMSELVES?

Some teachers are, yes. At ThoughtBox, we’ve had 3,500-4,000 teachers coming to us asking for climate education resources. One of the biggest challenges, however, is teacher confidence. Climate change raises a lot of issues, some of which may not seem directly related, like colonialism and social justice. Therefore, there are many different avenues to explore. A lot of teachers don’t know where to start and many are anxious about discussing potentially political issues in the classroom.

One of the things we’ve been talking about with the DfE is the need for teacher training. We run teacher training at ThoughtBox and also recommend an amazing organisation – Aimhi – that also works with teachers in this space. It begins by recognising that these issues will affect us all – emotionally as well as physically – and we can support our resilience and awareness through action and empowerment. This is what our CPD training is really focused on at ThoughtBox.

WHY DID YOU LEAVE TEACHING?

One of the reasons I left was a big dissatisfaction with an education system that is not helping young people prepare for the world they’re actually going to be living in. A lot of teachers are in a similarly desperate space – they don’t want to leave but don’t know how to continue.

HOW DID YOU BECOME INVOLVED WITH TEACH THE FUTURE?

I’ve been working in this space for seven years now, but I connected with Teach the Future in 2019, when it was quite a small network. Last year, I helped with a Teach the Teacher campaign, which was put together by students. It’s a one-hour training session that supports teachers in knowing how to talk about climate change with children.

WHAT ARE THE BENEFITS OF JOINING TEACH THE FUTURE’S TEACHERS NETWORK?

Joining the Teacher Network is a way of staying in the system but being part of a movement that’s working inside out. It’s a support network for teachers who don’t necessarily want to leave but don’t know where to start with climate education work.

IS THERE ANYTHING TEACHERS CAN DO TO START INTEGRATING CLIMATE CHANGE INTO THEIR LESSONS NOW?

The three things we talk about at ThoughtBox are: be brave, be safe and be connected.

Being brave is about having the conversations. Simply asking ‘Do any of you know anything about climate change?’ is a good start, even in the final five minutes of a lesson. It’s about showing students that you are also aware of climate change. You don’t need to know the answers as a teacher, simply welcome the conversations.

Being safe is about recognising that when you start to have these conversations, it will trigger different emotions in children. Some may not have thought about it; some may cry every night because they’re totally overwhelmed, and then there will be others experiencing different emotions on the spectrum. Create a safe and supportive space for this.

Being connected is about being part of a network, and knowing about other networks that support children with their questions and places to become active and empowered. It is also about helping children connect the dots on how their actions can impact wider system change.

WHAT MESSAGE WOULD YOU LIKE TO SEND TEACHERS WHO ARE READING THIS ARTICLE?

It’s time to talk. You don’t need to be an expert; you don’t need to know the answers, you don’t even need to know very much about it yourself. Just start the conversation. I think that’s where this work needs to begin. Don’t be afraid because we’re all in this together. It affects all of us.

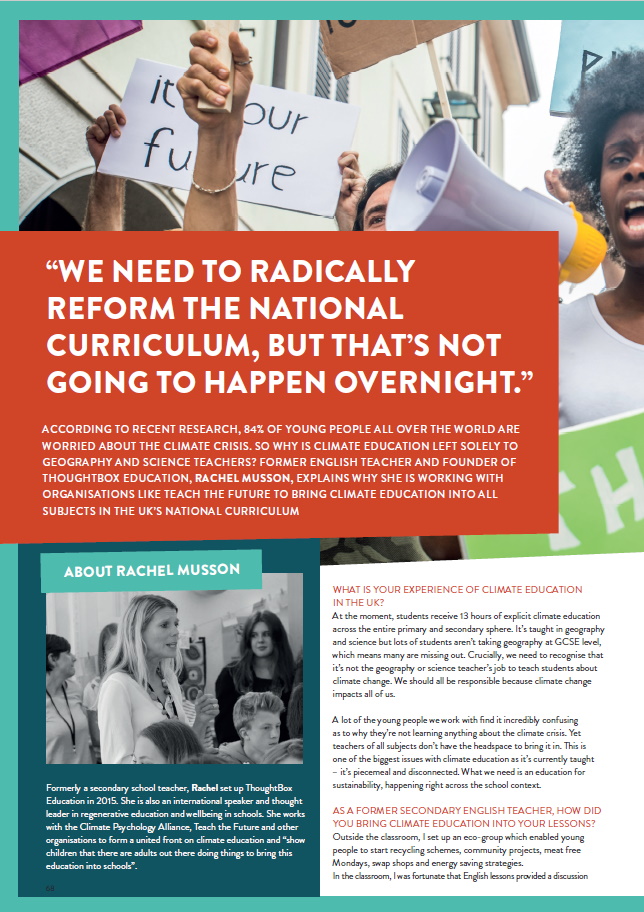

ABOUT RACHEL MUSSON

ABOUT RACHEL MUSSON

Formerly a secondary school teacher, Rachel set up ThoughtBox Education in 2015. She is also an international speaker and thought leader in regenerative education and wellbeing in schools. She works with the Climate Psychology Alliance, Teach the Future and other organisations to form a united front on climate education and “show children that there are adults out there doing things to bring this education into schools”.

RACHEL’S SUGGESTIONS FOR CLIMATE RESOURCES

• Teach the Future’s Teachers Network – a place for teachers across the UK to share resources and have chats with other teachers interested in climate education: www.teachthefuture.uk/action/teachers-network

• ThoughtBox offers a whole school approach to education for sustainability, including CPD, curriculum and leadership support. As a starter, the team has created a free toolkit for teachers to help young people start to make sense of the climate crisis: www.thoughtboxeducation.com/climatecurriculum (4,000 schools in 74 countries have already downloaded this resource).

• ThoughtBox’s short training video is also a good place to start for educators wondering how to respond to eco anxiety and support young people in schools: www.youtube.com/watch?v=GQxyMIksrtc

• Aimhi Earth – supported by the UN Environment Programme and others, Aimhi has produced a four-part, interactive online course to help people of all ages understand the climate and nature crisis: www.aimhi.earth/climate-course