What can the history of women’s suffrage teach us about women in politics today?

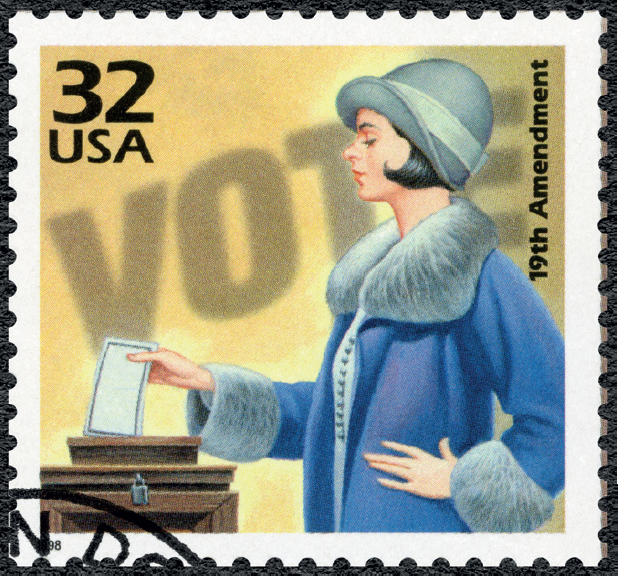

Although women’s suffrage has come a long way since 1893, when women in New Zealand were the first in the world to gain the right to vote in parliamentary elections, progress has not been easy, and we have still not achieved gender equality in politics. Dr Mona Morgan-Collins, a political scientist at King’s College London, UK, is exploring how women were represented in politics after suffrage, with the lessons she is learning having implications for politics today.

TALK LIKE A POLITICAL SCIENTIST

Electoral system — the rules used to determine the results of an election

Legislature — an assembly of people who have been elected to make laws for a state or a country

Polling station — a building where voters cast their vote during an election

Proportional representation (PR) — an electoral system in which parties gain seats in proportion to the number of votes cast for them

Single member plurality (SMP) — an electoral system in which the winning candidate is the one who gets the most votes. SMP is also known as ‘first past the post’

Substantive representation of women — representation of women’s interests in policies and legislatures

Suffrage — the right to vote in elections

Suffragist — a person who advocates for suffrage

Despite women’s right to vote now being a near-universal legal standard around the world, women are still under-represented in politics. “It remains common across countries and types of elections that women are less likely to vote, less likely to participate in other political activities and less likely to run for political office,” explains Dr Mona Morgan-Collins, a political scientist at King’s College London. This gender gap is largest in the top level of politics, where women continue to be less likely to be prime ministers or presidents, and less likely to rule in government offices. So, why have we still not achieved gender equality in politics?

When did women get the right to vote?

It is often thought that women’s suffrage came about in the early 20th century and that, before this, women had no access to politics. “However, history is rarely linear,” says Mona, who points out that several countries, including the UK, allowed rich widows to vote before this. Also, as countries began to give women the same voting rights as men, this right was often not extended to all women. In the US, for example, although some women could vote from 1920, full suffrage did not occur until 1965 when Black women were given the right to vote. “It has only been in the last few decades or so that suffrage for all women has become a standard across the globe,” explains Mona.

What challenges did women face when voting, even after suffrage?

“Women faced so many barriers!” says Mona. “It was really hard for women to vote back then.” Even after achieving suffrage, women faced cultural, structural and institutional barriers that prevented them from engaging in politics to the same extent as men. Society at the time viewed women as incapable of operating independently in politics and thought that women would, and should, vote in the same way as their husbands. These cultural beliefs did not change overnight once women had the legal right to vote.

Women were often expected to give up work when they married, meaning they did not have the same informal opportunities as men, for example through chatting with colleagues, to learn about and share opinions of politics. Women were less likely to have access to transport and more likely to have caring duties for children, so physically getting to the polling station was a greater challenge than for men.

Cultural and structural barriers to voting can undermine politicians’ incentives to mobilise voters. And, if politicians do not engage women voters in electoral campaigns, they hardly have an incentive to advocate for them once elected. Despite suffrage, politicians may be reluctant to represent women’s interests in their policies. The fact that, even today, women’s interests remain under-represented by politicians in most contexts is proof of this. After suffrage, as politicians believed that few women would vote and that those who did vote would do so in the same way as their husbands, and as politicians did not understand what women wanted from politics, women continued lacking substantive representation of their interests. Suffrage is a necessary condition for better representation, but not a sufficient condition.

The suffragists

The suffragists were those who campaigned, firstly for women’s right to vote, and then for women’s representation in politics. “The suffragists did so much more than just fight for suffrage,” says Mona, who has discovered that they were also crucial in the process of securing women’s representation after suffrage. They encouraged women to decide what issues mattered to them, educated women about politics and educated politicians about women. Politicians were more likely to represent women’s issues when women were viewed as capable individuals with defined interests. In Norway, for example, Mona’s research has shown that politicians from districts with strong suffragist movements advocated for financial support through pregnancy and easier access to divorce in the legislature, thanks to the influence of the suffragists’ voices.

However, the suffragists’ campaigns were defined by the women in the suffragist movement, who were predominantly white and middle class. This meant that the ‘women’s interests’ were only the interests of active, privileged women. As a result, the interests of all women were not represented. “But,” says Mona, “the concept of women’s interests had been born and could grow from there.”

How does Mona analyse voting behaviour?

Mona is interested in the voting behaviour of early women voters in different countries, and she is analysing a previously untapped wealth of data to explore this. In the past, women cast their votes in separate ballot boxes to men, allowing politicians of the time to know their voter demographics and allowing Mona to determine how many women compared with men voted at any given polling station. She also collects data from electoral registers, the lists of eligible voters that contain information such as age, sex, occupation and whether that individual voted, and she examines records of suffragists’ activities and politicians’ votes on policies in legislatures. By quantitatively analysing all these data, Mona is gaining insights into the voting behaviour of the first women able to vote, the responses of politicians to women’s suffrage and the importance of suffragists for both women’s voting and politicians’ responses to women in legislatures.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM311

© Gorodenkoff/stock.adobe.com

© auremar/stock.adobe.com

© Silvio/stock.adobe.com

© Silvio/stock.adobe.com

© Popova Olga/stock.adobe.com

© Wirestock/stock.adobe.com

What else has Mona discovered?

While previous studies had shown that the type of electoral system used in a country influenced women’s voting turnout, with women being more likely to vote in proportional representation (PR) systems than in single member plurality (SMP) systems, the reasons behind this were never fully understood. Mona investigated this and found that electoral competition had a more powerful effect on women’s turnout.

She discovered some SMP countries had higher turnouts of women than PR countries if the electoral districts were competitive, while some PR countries had low turnouts of women if political parties did not have a stable geographically-bounded support base. “This is because high district competition in SMP and high geographical concentration of electoral support in PR increase the overall incentive of all voters, regardless of gender, to vote,” says Mona.

For example, when women gained suffrage in New Zealand, with an SMP system, they were almost as likely to vote as men due to the competitive nature of politics in the country at the time. Politicians were therefore incentivised to mobilise women to vote, and women were more likely to do so. In contrast, women’s turnout in Chile, with a PR system, was very low after suffrage as political parties at the time could not rely on stable support from local strongholds. Electoral competition, rather than the electoral system, contributed to the extent women voted in equal numbers to men, and therefore the likelihood of politicians representing women’s interests.

What next for women in politics?

“We know that women’s suffrage is necessary for women’s participation and representation in politics,” says Mona, but she argues that suffrage alone is not sufficient. “Something more needs to happen to ensure women’s right to vote leads to politicians developing policies that improve women’s substantive representation.” Mona’s research uncovers how things used to be done in the past, which is essential if we want to know how to improve politics and policies in the present. “If we want to improve representation of women’s interests today, we have to bring more women into politics and have collective discussions of what women’s interests are,” says Mona. “Women’s organisations can achieve both. The suffragists did. It is only when women’s movements are strong and electoral competition is favourable that politicians will adopt policies that represent women’s interests.”

DR MONA MORGAN-COLLINS

DR MONA MORGAN-COLLINS

Department of Political Economy, School of Politics and Economics, King’s College London, UK

Fields of research: Political Science, Political Economy

Research project: Exploring women’s voting behaviour and substantive representation in politics by examining women’s suffrage

Funder: Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) This work was supported by the ESRC, grant number ES/T01394X/1, ‘From Suffrage to Representation’

ABOUT POLITICAL SCIENCE

Political science is the study of governments and political systems at local, national and international levels. If you study political science, you will learn about democracy, investigate political systems in different countries, analyse past and current political behaviour, and examine political theories. This is different from the study of politics, which examines the state of affairs in a country, and it is important to note that you do not need to enjoy politics to enjoy political science: “Those interested in political science may not even be interested in politics, like me!” says Mona.

Political science research often draws on many different disciplines, such as economics, sociology and history. Mona is a lecturer of political economy, a field that combines politics and economics. “Most social science research is interdisciplinary,” she explains. “I study a core political science topic – voting behaviour and representation. To understand this, I use methods and theories from economics, gender studies and history.”

Communicating political science research to politicians, policymakers and the public is just as important as the research itself, as it allows people outside academia to learn from and act on the research findings. “Some people might ask whether research on suffragists in Norway and Chile 100 years ago has any relevance to today’s practitioners,” says Mona. “But it does.” For example, as women were absent from government politics at the time of suffrage, politics happened within women’s organisations such as the suffragists. “This offers a window of opportunity to understand the impact of women’s groups, something that is hard to isolate from the impact of women politicians in recent times.”

As we continue to work towards achieving better representation of women’s interests in politics, we have a lot to learn from the politics of the past that successfully improved women’s representation.

Pathway from school to political science

• As well as studying humanities and social science subjects at school, such as history, economics and sociology, Mona highlights that maths and statistics are key for political science research. Her research involves quantitative data analysis, but even if you are interested in qualitative research or want to become a politician, you will still need to understand quantitative political science research.

• If you’re interested in political science, Mona suggests looking online to find political science reading lists compiled by academics. These will direct you to relevant articles that will introduce you to current theories and ideas in the field.

• Many universities offer degrees in political science, politics, international relations or politics, philosophy and economics, all of which could lead to a career in political science. To become a researcher, you will then usually have to complete a PhD.

• Visit the School of Politics and Economics at King’s College London to learn more about the different degree programmes you could study: www.kcl.ac.uk/politics-economics

Explore careers in political science

• As a political science researcher, you can focus on whichever aspect of politics most interests you. While Mona studies political history in the context of women’s suffrage, you could investigate the influence of modern political practices on policies or examine how politics in different countries contribute to international relationships.

• A degree in political science will provide you with the skills and knowledge needed to work in policymaking, government departments, non-governmental organisations and political parties. “There is not one way to use a political science degree,” says Mona. “That’s the most exciting part. You can define your specific interests, pursue them, and see where they lead.”

Meet Mona

Q&A

When did your interest in political science begin?

Growing up, I hated politics! I enjoyed reading anything I came across, but always avoided following politics. As a teenager, I entertained different ideas of who I wanted to become – a lawyer, a psychologist, a biologist, an actress… I’m grateful for the chance to have explored different interests and considered different careers.

Then one day, I learned about the power of electoral systems and how they can determine who wins elections. These are simple rules that we put in place and then they shape who governs. Sometimes different people can get elected under different systems, even if the preferences of voters don’t change. That fascinated me. I learnt everything I could about electoral systems and decided to pursue this fascination for a career.

What inspired you to become a political scientist?

When I was growing up, women were rarely visible in politics and political science was dominated by men, so I did not have any role models. None of the books I was reading about electoral systems at that time were written by women. I realised that if there were no women writing books about this topic, it was time for me to write one. Somebody should, so why not me?

What personal qualities have helped you become a successful researcher?

Resilience and persistence. As a researcher, you are bound to encounter setbacks – models not working, data collection falling apart or finding the opposite of what you thought you would find. You will sometimes find people who put down your capabilities or who won’t believe your work is worthwhile. A researcher needs a tough skin to work through these difficulties. The one thing that always helped me was the belief that even if things were hard, I would eventually find my way through. And so far, I always have done, even if this meant following a different path to the one I imagined.

What have been the highlights of your career?

I loved having the opportunity to spend time conducting research at the University of Oxford, UK, and Harvard University, USA. Being exposed to different academic environments and scholars is not only professionally stimulating but also very personally rewarding. The real highlights are the outputs of my work, which have been published in top political science journals. Knowing that my work is inspiring students and scholars to pursue their own research ideas is a sign of professional success and is very satisfying.

What are your ambitions for the future?

I want to keep doing good research that will shape our knowledge in the field of political economy. There is still so much I want to learn about early women voters and women’s political representation!

What do you enjoy doing in your free time?

I used to spend my free time with books and yoga. Now, I spend it with my 2-year-old daughter and my small fluffy dog, Artichoke. There is very little that is more relaxing than a walk in the park with the two of them.

Mona’s top tips

1. Read, read and read! Then discuss what you have read with others.

2. Figure out what your interests are and follow your curiosity. Opportunities will come!

3. Do not be afraid to change paths. Learning that something is not the right path for you is just as important as figuring out that something is.

Do you have a question for Mona?

Write it in the comments box below and Mona will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)