What happened when Henry VIII went on tour?

Most summers during his reign, King Henry VIII and his court set out from London to visit a different part of England. These ‘progresses’ involved feasts, processions, jousting tournaments, hunting and dancing, serving Henry’s personal and political interests. Professor Anthony Musson at Historic Royal Palaces and Dr John Cooper at the University of York, UK, are delving deeper into what occurred during these extravagant affairs

TALK LIKE A TUDOR HISTORIAN

CHIVALRY – a set of moral and social values first developed in the Middle Ages, instructing knights and nobles how to behave on and off the battlefield

GIESTS – the written schedules and instructions for the royal progresses

HENRY VIII – the second Tudor monarch, who ruled between 1509 and 1547

JOUSTING – a popular Tudor sport where horse riders would charge towards each other and aim to break their wooden lances on their opponents, showing off their bravery and skill

ROYAL COURT – the people who lived and worked with the king and queen, including nobles, royal guards, servants and musicians. Higher-ranking members of the court were called ‘courtiers’

ROYAL PROGRESS – the summer tour taken by Tudor monarchs and their courts

TUDORS – a royal family which ruled England between 1485 and 1603. Many sweeping changes to England’s culture, politics and religion took place during their reign

Known for chopping off the heads of his wives and for abolishing the Catholic church in England, Henry VIII is probably the country’s most famous (or infamous) king. Owing to his extravagant lifestyle, including his series of six unfortunate wives, Henry VIII has captured the public’s imagination for over 500 years. Yet despite being one of England’s best-studied monarchs, historians still have many questions about some aspects of life during Henry’s fascinating reign.

Most years, Henry and members of his court would travel to a different part of England in a series of grandiose tours named ‘royal progresses’. “The progresses usually took place during the summer and could last up to three or four months,” explains Professor Anthony Musson, Head of Research at Historic Royal Palaces. “Their emphasis was on splendour and ceremonial display, and the king was greeted with pageantry on approach to the gates of the city he was visiting.”

Due to the scarcity of surviving historical records, there is much that we still do not know about the nature of these progresses and the organisational logistics required to host them. Anthony and his colleague, Dr John Cooper at the University of York, are hoping to discover what impact Henry’s progresses had on England’s culture and politics.

WHAT HAPPENED ON THE ROYAL PROGRESSES?

Formal ceremonies played an important role on the progresses. Henry would be welcomed into the hosting city with a series of stage-managed processions before being greeted by important nobles and courtiers. Gifts would be exchanged as a sign of friendship, and lavish banquets would be prepared.

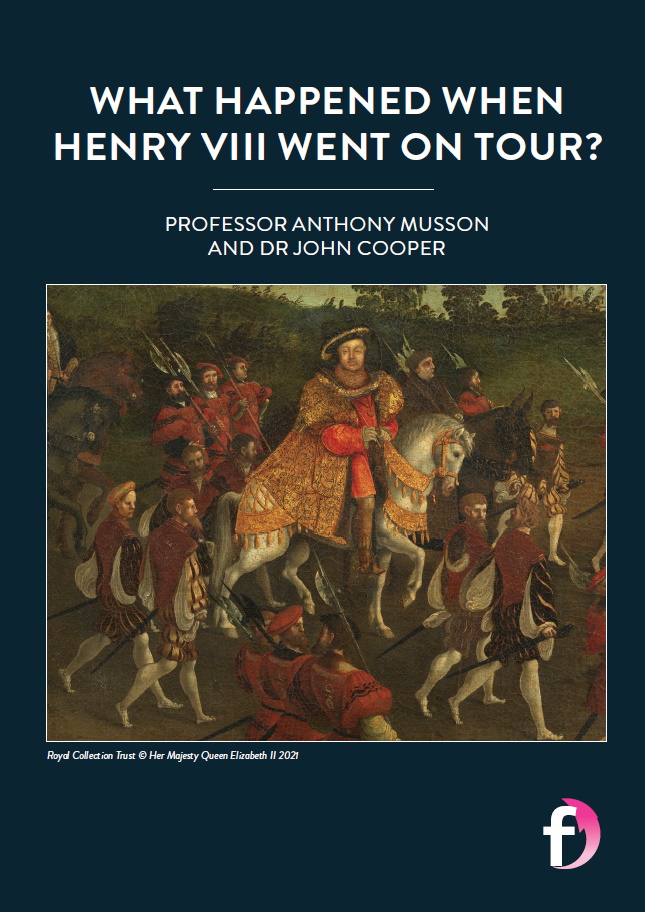

The progresses allowed Henry to enjoy his two favourite hobbies, hunting and jousting. As well as providing personal entertainment, these activities had deeper political motives. Trusted courtiers were invited to participate in hunts and were rewarded with venison for their loyalty. Henry himself competed in jousting tournaments in the early years of his reign, displaying his strength and prowess to his watching subjects. These tournaments encouraged a competitive spirit among the knights of the realm and promoted the values of chivalry, which were highly important in Tudor society.

The purpose of the progresses was to display Henry’s authority throughout the nation and beyond. But as John explains, these events did not always go to plan. “The City of York hosted Henry VIII in 1541, when the king travelled north to meet his nephew King James V of Scotland,” he says. “Unfortunately, James didn’t show up!” Henry himself also caused disruption to the schedule of the progresses. “Henry was desperate to avoid the plague so he would often divert the route or cancel his visits,” says Anthony. “And sometimes he just went ‘off script’ and did things spontaneously!”

One of the most successful progresses took place in 1520, when Henry travelled across the English Channel to meet with King François I of France. That trip was so magnificent that it became known as ‘The Field of Cloth of Gold’.

WHY WERE THE PROGRESSES NECESSARY?

Monarchs had always journeyed around their realm. But by the mid-1530s, Henry VIII’s actions as king had triggered enormous religious and political shifts in English society. There was an ever-present risk that his subjects would become dissatisfied, and possibly even rebel against him. In the face of this challenge, the royal progresses ensured that people all over England, from the nobles to the ordinary working folk, continued to comply with Henry’s rule.

“In theory, progresses united the nation,” Anthony explains. “Towns and cities pledged their loyalty to the king through stage-managed civic displays, and innkeepers, shopkeepers and craftworkers could take economic advantage of the large influx of visitors.”

From a practical point of view, the progresses meant that Henry’s London palaces, like Hampton Court, were empty for several months. This allowed repairs to be carried out, but more importantly provided an opportunity for servants to empty the lavatories!

WHAT WERE THE LOGISTICAL CHALLENGES OF THE PROGRESSES?

“The progresses were a logistical nightmare!” says Anthony. “Especially as Henry did not travel light and his entourage was considerable.” Clearly, uprooting a large part of the royal court from London every year was an enormous undertaking. Instructions for the tours (known as ‘giests’) were published five months before the court set off, allowing organisers to plan every last detail.

All the supplies needed to keep Henry’s entourage (including nobles, servants and even horses) fed and comfortable were secured well in advance of the progress’s arrival in each town. “Royal purveyors and clerks would ride ahead securing provisions from towns, while local notables would provide gifts of food and wine for the royal court,” Anthony says. “The costs of a royal visit were considerable and although the expense was supposed to be met from the royal coffers, Henry frequently relied on local generosity and the willingness of his subjects to please their king.”

When the progress arrived at the house where they were staying, Henry and his queen would be given the finest accommodation available. Some courtiers built entire new wings to their houses, at vast personal expense, in the hope of impressing the king. But there was rarely enough space for the rest of his court. To provide the necessary sleeping quarters and reception areas, organisers often constructed grand and luxurious tents, dubbed ‘portable palaces’.

WHAT DO ANTHONY AND JOHN HOPE TO DISCOVER?

The giests provide the best source of information about the itineraries, baggage and members of Henry’s progresses, but not all of them have survived the centuries. To supplement these scarce records, Anthony and John are combing through other sources, including diplomatic reports, church registers, private letters between court officials and inventories of noble households.

They are hoping to build a fuller picture of what went on during Henry’s lavish tours. Who went hunting with the king, and what political deals were struck? What role did the queen play on progress? What were the positive and negative impacts on the local community? Even, what were the acoustics like in the venues where performances and religious services were held? Alongside unravelling the many remaining mysteries surrounding the progresses, Anthony and John are also organising talks and workshops for historians, students and members of the public, including pitching a full-sized replica of a portable palace tent in York!

Ultimately, Anthony and John hope to improve our understanding of just how important Henry VIII’s royal progresses were in shaping Tudor society, while bringing the full extravagance of the famous king’s court to life.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM187

CHIVALRY – a set of moral and social values first developed in the Middle Ages, instructing knights and nobles how to behave on and off the battlefield

GIESTS – the written schedules and instructions for the royal progresses

HENRY VIII – the second Tudor monarch, who ruled between 1509 and 1547

JOUSTING – a popular Tudor sport where horse riders would charge towards each other and aim to break their wooden lances on their opponents, showing off their bravery and skill

ROYAL COURT – the people who lived and worked with the king and queen, including nobles, royal guards, servants and musicians. Higher-ranking members of the court were called ‘courtiers’

ROYAL PROGRESS – the summer tour taken by Tudor monarchs and their courts

TUDORS – a royal family which ruled England between 1485 and 1603. Many sweeping changes to England’s culture, politics and religion took place during their reign

Known for chopping off the heads of his wives and for abolishing the Catholic church in England, Henry VIII is probably the country’s most famous (or infamous) king. Owing to his extravagant lifestyle, including his series of six unfortunate wives, Henry VIII has captured the public’s imagination for over 500 years. Yet despite being one of England’s best-studied monarchs, historians still have many questions about some aspects of life during Henry’s fascinating reign.

Most years, Henry and members of his court would travel to a different part of England in a series of grandiose tours named ‘royal progresses’. “The progresses usually took place during the summer and could last up to three or four months,” explains Professor Anthony Musson, Head of Research at Historic Royal Palaces. “Their emphasis was on splendour and ceremonial display, and the king was greeted with pageantry on approach to the gates of the city he was visiting.”

Due to the scarcity of surviving historical records, there is much that we still do not know about the nature of these progresses and the organisational logistics required to host them. Anthony and his colleague, Dr John Cooper at the University of York, are hoping to discover what impact Henry’s progresses had on England’s culture and politics.

WHAT HAPPENED ON THE ROYAL PROGRESSES?

Formal ceremonies played an important role on the progresses. Henry would be welcomed into the hosting city with a series of stage-managed processions before being greeted by important nobles and courtiers. Gifts would be exchanged as a sign of friendship, and lavish banquets would be prepared.

The progresses allowed Henry to enjoy his two favourite hobbies, hunting and jousting. As well as providing personal entertainment, these activities had deeper political motives. Trusted courtiers were invited to participate in hunts and were rewarded with venison for their loyalty. Henry himself competed in jousting tournaments in the early years of his reign, displaying his strength and prowess to his watching subjects. These tournaments encouraged a competitive spirit among the knights of the realm and promoted the values of chivalry, which were highly important in Tudor society.

The purpose of the progresses was to display Henry’s authority throughout the nation and beyond. But as John explains, these events did not always go to plan. “The City of York hosted Henry VIII in 1541, when the king travelled north to meet his nephew King James V of Scotland,” he says. “Unfortunately, James didn’t show up!” Henry himself also caused disruption to the schedule of the progresses. “Henry was desperate to avoid the plague so he would often divert the route or cancel his visits,” says Anthony. “And sometimes he just went ‘off script’ and did things spontaneously!”

One of the most successful progresses took place in 1520, when Henry travelled across the English Channel to meet with King François I of France. That trip was so magnificent that it became known as ‘The Field of Cloth of Gold’.

WHY WERE THE PROGRESSES NECESSARY?

Monarchs had always journeyed around their realm. But by the mid-1530s, Henry VIII’s actions as king had triggered enormous religious and political shifts in English society. There was an ever-present risk that his subjects would become dissatisfied, and possibly even rebel against him. In the face of this challenge, the royal progresses ensured that people all over England, from the nobles to the ordinary working folk, continued to comply with Henry’s rule.

“In theory, progresses united the nation,” Anthony explains. “Towns and cities pledged their loyalty to the king through stage-managed civic displays, and innkeepers, shopkeepers and craftworkers could take economic advantage of the large influx of visitors.”

From a practical point of view, the progresses meant that Henry’s London palaces, like Hampton Court, were empty for several months. This allowed repairs to be carried out, but more importantly provided an opportunity for servants to empty the lavatories!

WHAT WERE THE LOGISTICAL CHALLENGES OF THE PROGRESSES?

“The progresses were a logistical nightmare!” says Anthony. “Especially as Henry did not travel light and his entourage was considerable.” Clearly, uprooting a large part of the royal court from London every year was an enormous undertaking. Instructions for the tours (known as ‘giests’) were published five months before the court set off, allowing organisers to plan every last detail.

All the supplies needed to keep Henry’s entourage (including nobles, servants and even horses) fed and comfortable were secured well in advance of the progress’s arrival in each town. “Royal purveyors and clerks would ride ahead securing provisions from towns, while local notables would provide gifts of food and wine for the royal court,” Anthony says. “The costs of a royal visit were considerable and although the expense was supposed to be met from the royal coffers, Henry frequently relied on local generosity and the willingness of his subjects to please their king.”

When the progress arrived at the house where they were staying, Henry and his queen would be given the finest accommodation available. Some courtiers built entire new wings to their houses, at vast personal expense, in the hope of impressing the king. But there was rarely enough space for the rest of his court. To provide the necessary sleeping quarters and reception areas, organisers often constructed grand and luxurious tents, dubbed ‘portable palaces’.

WHAT DO ANTHONY AND JOHN HOPE TO DISCOVER?

The giests provide the best source of information about the itineraries, baggage and members of Henry’s progresses, but not all of them have survived the centuries. To supplement these scarce records, Anthony and John are combing through other sources, including diplomatic reports, church registers, private letters between court officials and inventories of noble households.

They are hoping to build a fuller picture of what went on during Henry’s lavish tours. Who went hunting with the king, and what political deals were struck? What role did the queen play on progress? What were the positive and negative impacts on the local community? Even, what were the acoustics like in the venues where performances and religious services were held? Alongside unravelling the many remaining mysteries surrounding the progresses, Anthony and John are also organising talks and workshops for historians, students and members of the public, including pitching a full-sized replica of a portable palace tent in York!

Ultimately, Anthony and John hope to improve our understanding of just how important Henry VIII’s royal progresses were in shaping Tudor society, while bringing the full extravagance of the famous king’s court to life.

PROFESSOR ANTHONY MUSSON

PROFESSOR ANTHONY MUSSON

Historic Royal Palaces, UK

DR JOHN COOPER

University of York, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Tudor History

RESEARCH PROJECT: Investigating the hidden details of Henry VIII’s royal progresses

FUNDER: Arts and Humanities Research Council

PROFESSOR ANTHONY MUSSON

PROFESSOR ANTHONY MUSSON

Historic Royal Palaces, UK

DR JOHN COOPER

University of York, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Tudor History

RESEARCH PROJECT: Investigating the hidden details of Henry VIII’s royal progresses

FUNDER: Arts and Humanities Research Council

ABOUT TUDOR HISTORY

WHY ARE WE STILL SO FASCINATED BY THE TUDORS?

Elizabeth I’s reign ended in 1603, yet the Tudors continue to enthral us over 400 years later. Anthony believes there are many reasons for this. “The splendour and ceremony of the Tudor royal court, the love stories and tragedies surrounding Henry VIII’s wives, the ‘rags to riches’ tales of courtiers and their eventual fall from grace, and the revolutionary changes in religion, politics and culture all capture our imagination,” he says.

Much of this intriguing history lives on in beautiful buildings still found all over England, which you can visit to gain an insight into the lives of the people who once lived there. Tudor art, music and drama are still performed and enjoyed today, and have inspired many modern books and films.

WHAT ARE THE HIGHLIGHTS OF BEING A TUDOR HISTORIAN?

“There are lots of great things about being a professional historian,” says John. “Reading original manuscripts in the British Library, corresponding with scholars around the world, talking with students who are just as excited about the past as you are…”

Both John and Anthony agree that the opportunity to spend time in historic locations is one of the best things about being a historian, allowing them to go behind the scenes and immerse themselves in the past. Anthony is based at Hampton Court Palace, one of Henry VIII’s favourite London residences, where he oversees a variety of exciting research projects with Historic Royal Palaces. “I love walking through the grounds at Hampton Court when no tourists are about,” he says. “It never ceases to amaze me how beautiful the setting is, and I have to pinch myself that Henry VIII and so many historical characters actually lived here!”

No two days are ever the same for Anthony and John. Their work involves visiting historical sites, examining ancient manuscripts, paintings and artefacts, and establishing new research projects. And they do not just collaborate with scholars, but with craftspeople, cooks and gardeners, who study Tudor sources to make furniture, feasts and flowerbeds that are as historically accurate as possible.

WHAT DO WE STILL NOT KNOW ABOUT THE TUDORS?

As the Tudors lived over 400 years ago, the surviving written records are scattered across many locations. Historians must piece together information from different sources to build a picture of Tudor life and society. They are constantly searching for new methods to understand how Tudor people experienced the historical events we read about, which often requires re-interpreting historical sources from different points of view.

While Tudor scribes recorded tales of kings and courtiers, we know much less about the experiences of ordinary people. Those living outside the lavish palaces and country estates (farm labourers, teachers, tradespeople…) were not considered worthy of having their lives recorded. Anthony and John are hoping to uncover the hidden experiences of the common people, allowing their stories to finally be shared with the modern world.

EXPLORE A CAREER AS A TUDOR HISTORIAN

• If you live in the UK, there could be a fascinating Tudor site near you. Visit Historic Royal Palaces (www.hrp.org.uk), the National Trust (www.nationaltrust.org.uk), English Heritage (www.english-heritage.org.uk) or Historic Houses (www.historichouses.org) to find out more.

• There are many great books, TV shows and online resources to explore the Tudors and other historical periods beyond your school history lessons. Anthony recommends the Horrible Histories series!

• Do you live near a museum or historical site? Ask about volunteering opportunities – it will be an excellent way to learn what historical work involves and will look great on your university application.

• Getting a job in a museum is competitive, but John believes that the destination is worth the journey.

• Try to have an appreciation for all historical periods. Your school curriculum will only cover a tiny snapshot of the history of the world, so investigate other time periods in other cultures. Explore the aspects of the past that interest you.

• Never be afraid to ask your history teachers and tutors questions about what you see and read.

• Most universities offer history degrees. Look for courses taught by professors specialising in the Tudors.

HOW DID ANTHONY BECOME A HISTORIAN?

I have been a musician for most of my life and enjoy composing, singing and playing the piano and organ. I was a chorister at Westminster Abbey from the age of 8 to 13. Singing in such historical surroundings at state occasions and famous memorial services definitely inspired my interest in history.

I was also very interested in churches. Exploring local parish churches or grand cathedrals is a great way to appreciate history. They are not just religious buildings, but microcosms of the concerns of past societies.

I didn’t have an option to study the Tudors at A-level, so I first became fascinated with them at university. Some of my lecturers were dauntingly eminent, but usually very approachable. They encouraged me to be critical and to have my own opinions, important traits for a historian.

Working in Hampton Court Palace is an incredible privilege. I love my office as it overlooks the Chapel Royal and I can sometimes hear the organ or singing wafting up. There is also a secret passage that leads downstairs and comes out behind a tapestry just by the Great Hall. And I love the fantastic views from the roof of the palace, over the gardens to the parks and River Thames beyond.

My favourite fact about Henry VIII is that he was an accomplished musician, both playing and composing. It balances the military side to him!

HOW DID JOHN BECOME A HISTORIAN?

I’ve always been interested in the past. As a boy, I loved reading books about knights and castles and the unexplained mysteries of history. I was fascinated with the ‘lost colony’ of Roanoke Island, the first English people to try to settle in America. They disappeared, but left a strange message carved into a tree – what did it mean?

My inspiration as a historian was sparked by childhood visits to places like Pendennis Castle in Cornwall, built by Henry VIII to protect England from invasion. At school, I did a project on the Tudor warship the Mary Rose. It was amazing to watch it emerge from the bottom of the Solent live on TV, though there was a terrifying moment when the crane slipped and nearly dropped the ancient wreck back into the sea!

As a teenager I thought I might become an archaeologist, so I’m delighted now to be working alongside archaeologists on history projects like this one.

For me, the highlight of this project has been to get behind-the-scenes access to some of the palaces and houses owned by Henry VIII, particularly Hampton Court where we held one of our workshops. Henry VIII owned more than 50 royal palaces by the end of his reign!

I’m lucky to live in a Yorkshire village, with a garden which I have gradually transformed into a wildlife haven – a pond, shrubs chosen for bees and butterflies, a couple of native trees. It’s been great to see how even a smallish space can be transformed into a home for wildlife.

I am motivated by a belief that we need to cherish what survives of the past and be prepared to defend it.

ANTHONY AND JOHN’S TOP TIPS

01 Visit museums and historical sites. They will provide fascinating insights into past cultures.

02 Reading both fiction and non-fiction is a good way of exploring the past. It can be difficult to appreciate historical lives, but some novelists are very good at capturing the essence of historical periods and bringing them alive.

03 Think critically about what you read. Historians don’t automatically accept each other’s opinions, and there is no reason that you should either.

Do you have a question for Anthony or John?

Write it in the comments box below and Anthony or John will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)