What if we could do psychology experiments in virtual reality?

Virtual reality is opening new doors for research in psychology. Based at the University of Kent in the UK, Professor Markus Bindemann and his team build photorealistic, 3D avatars in virtual reality to study face perception and person perception

TALK LIKE A VR PSYCHOLOGIST

VIRTUAL REALITY (VR) – A three-dimensional (3D), simulated audio-visual experience or environment, usually accessed using a headset and handheld controllers

AVATAR – An image representing a person on the internet or in virtual reality

FACE PERCEPTION – The ability to understand human faces, including the ability to distinguish faces from other objects, to recognise familiar faces, and to detect emotional expressions

PERSON PERCEPTION – The process of forming an impression of another person, based on what they look and sound like, how they move, and other factors

FACE-IDENTITY MATCHING – The ability to identify a person by comparing their face to a photograph

SIMILARITY SPACE – A numerical framework that captures how similar different faces in a set are in appearance to each other, by comparing scores that reflect the visual similarity of all possible combinations of faces

Psychological research into human thinking and behaviour is difficult because so many factors influence the human mind. In a lab experiment, psychologists can isolate the factors they want to study by controlling the research environment – but the results can be unrealistic because participants might behave differently in the lab than in complex real-world situations. In field studies, psychologists can learn about behaviour in real life, but it is difficult to disentangle all the possible reasons for people’s actions. So, how can psychologists combat the issues related to both lab and field studies? Professor Markus Bindemann, of the University of Kent in the UK, has a solution to this dilemma: psychology experiments in virtual reality.

In virtual reality, researchers have complete control over the environment. Because VR simulations can be so realistic, however, study participants behave like they do in real life. Markus uses this powerful advantage to study face-identity matching – the ability of people to match human faces to photographs.

A lab experiment might show participants a plain, cropped headshot and ask them to match the photograph to a person, then use psychological or neuroscientific research tools to study how their brains complete the task. The photographs are standardised and carefully designed to remove any sources of bias or other interfering factors. How does this kind of experiment translate into the real-world environment of, say, a passport control line, where passport controllers are under time pressure, lighting may vary, and there are noises and other distractions? More pertinent for Markus and his team, how can VR offer a useful alternative?

“VR allows for sophisticated measurement of behaviour in complex environments,” explains Markus. “We can look at participants’ accuracy and response times (via button presses on hand-held controllers), movement coordinates (for example, how close a participant moves to an avatar in a VR world), and eye movements to see what participants are actually looking at (via integrated eye-trackers in VR headsets for research).” As a research tool, VR offers Markus and his team so much more than a cropped headshot!

CAN VR EXPERIMENTS TELL US HOW PEOPLE IDENTIFY IMPOSTORS?

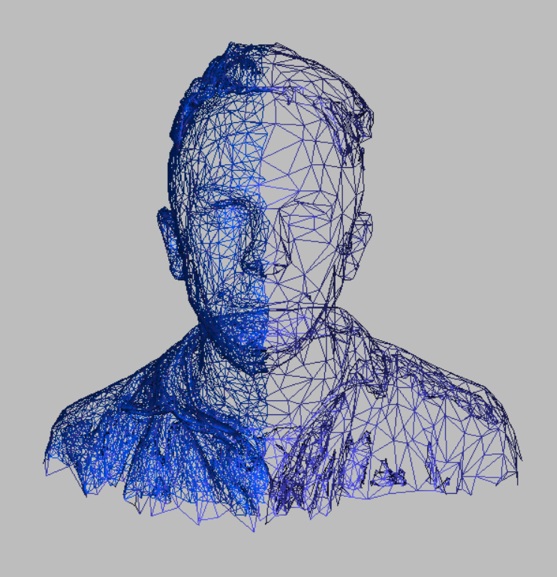

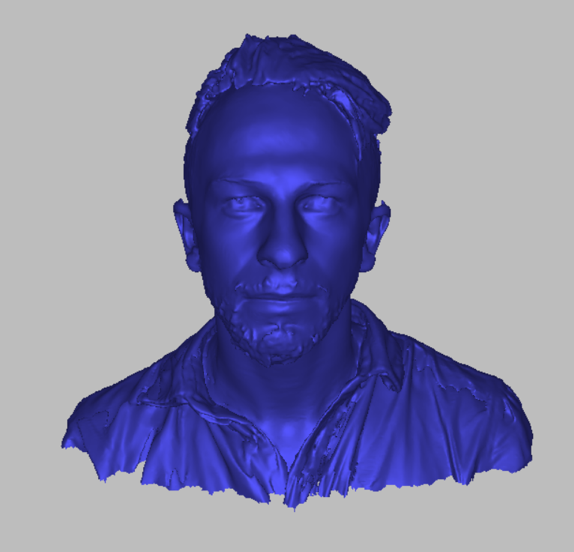

To answer this and other questions, Markus and his team built a virtual reality passport control game. They create realistic avatars of real people by using handheld scanners to generate a 3D model of a volunteer’s head. The head is then attached to an avatar body and the body rigged with a skeleton so it can move around in VR. The clothing, body size and other elements of the avatar’s appearance can be varied. Participants in the study then ‘play’ as the passport controller in an airport, checking the faces of avatars against a passport photograph as the avatars file through the control booth.

“This scenario investigates the real-world phenomenon of identity-impostors,” Markus says. “Modern passports are extremely difficult to forge but, for people with criminal intentions, one way of passing through security undetected is to utilise the identity documents of someone with a similar appearance.” The research team can investigate how different factors affect participants’ ability to accurately match faces to photographs by changing the VR scenario a little bit at a time. “We have variations of this task to understand what might impact identification accuracy at airports,” Markus explains. “For example, do agitated crowds (versus orderly queues) of waiting travellers in an airport exert time pressure on the passport controller and increase the failure to detect impostors?”

AVATARS AS A RESEARCH TOOL

As with any research method, Markus and his team have had to assess and evaluate the quality of their avatars rigorously. “We have examined how well observers can recognise avatars of people that they know, and the answer is they can recognise these as well as photographs. We have performed computations to measure how similar avatars of different people are to each other – and we found that this produces the same ‘similarity space’ as photos of the same people. And we have compared person identification of avatars in our virtual airport with established laboratory tasks that measure face identification and have found strong correspondence there.”

Developing such high-quality avatars has been challenging but will help to drive on Markus’s research for years to come. “It is complex and sophisticated technology, and we also put it to complex and sophisticated use,” he explains. “I lead a research team which works on this, so much of my role is to coordinate and make key decisions. My research assistants were completely new to this technology at the start of this project, but have learned to scan and build avatars, and to run experiments in VR in the space of a couple of years.”

For Markus and his team, developing avatars has been professionally and academically rewarding. “It has been a really fun journey of discovery,” says Markus. “Making the first 3D scans of people, for example, was hugely exciting. And it continues to be really interesting for us to see how well we can scan different people and convert these into avatars – for example, someone with dreadlocks, long curly hair, a beard or distinctive facial marks.”

WHAT’S NEXT FOR PSYCHOLOGY IN VR?

Markus’ avatars cannot yet talk, interact, or change their facial expressions. Making the simulations more sophisticated is the team’s immediate goal, with the aim of gaining a better understanding of face and person perception. This has the potential to help people with facial recognition disorders, to improve security systems, and to interpret the reliability of eyewitness testimony in court cases, among many other possible applications.

In the long term, the potential of VR for psychology and neuroscience is enormous and goes far beyond face perception or passport control. “I know psychologists who are using VR for research in forensic settings, in sports science, or in clinical settings,” says Markus. Researchers across the psychological disciplines are now carrying out experiments in VR to study, for example, how people communicate and interact with each other, how people navigate through complex environments, or to provide novel treatments for addictions or anxiety disorders.

PROFESSOR MARKUS BINDEMANN

PROFESSOR MARKUS BINDEMANN

Professor of Cognitive Psychology, University of Kent, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Cognitive psychology, Neuropsychology, Visual Perception

RESEARCH PROJECT: Investigating face perception and face-identity matching in virtual reality.

FUNDERS: Economic and Social Research Council (Grant no ES/S010181/1)

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM160

VIRTUAL REALITY (VR) – A three-dimensional (3D), simulated audio-visual experience or environment, usually accessed using a headset and handheld controllers

AVATAR – An image representing a person on the internet or in virtual reality

FACE PERCEPTION – The ability to understand human faces, including the ability to distinguish faces from other objects, to recognise familiar faces, and to detect emotional expressions

PERSON PERCEPTION – The process of forming an impression of another person, based on what they look and sound like, how they move, and other factors

FACE-IDENTITY MATCHING – The ability to identify a person by comparing their face to a photograph

SIMILARITY SPACE – A numerical framework that captures how similar different faces in a set are in appearance to each other, by comparing scores that reflect the visual similarity of all possible combinations of faces

Psychological research into human thinking and behaviour is difficult because so many factors influence the human mind. In a lab experiment, psychologists can isolate the factors they want to study by controlling the research environment – but the results can be unrealistic because participants might behave differently in the lab than in complex real-world situations. In field studies, psychologists can learn about behaviour in real life, but it is difficult to disentangle all the possible reasons for people’s actions. So, how can psychologists combat the issues related to both lab and field studies? Professor Markus Bindemann, of the University of Kent in the UK, has a solution to this dilemma: psychology experiments in virtual reality.

In virtual reality, researchers have complete control over the environment. Because VR simulations can be so realistic, however, study participants behave like they do in real life. Markus uses this powerful advantage to study face-identity matching – the ability of people to match human faces to photographs.

A lab experiment might show participants a plain, cropped headshot and ask them to match the photograph to a person, then use psychological or neuroscientific research tools to study how their brains complete the task. The photographs are standardised and carefully designed to remove any sources of bias or other interfering factors. How does this kind of experiment translate into the real-world environment of, say, a passport control line, where passport controllers are under time pressure, lighting may vary, and there are noises and other distractions? More pertinent for Markus and his team, how can VR offer a useful alternative?

“VR allows for sophisticated measurement of behaviour in complex environments,” explains Markus. “We can look at participants’ accuracy and response times (via button presses on hand-held controllers), movement coordinates (for example, how close a participant moves to an avatar in a VR world), and eye movements to see what participants are actually looking at (via integrated eye-trackers in VR headsets for research).” As a research tool, VR offers Markus and his team so much more than a cropped headshot!

CAN VR EXPERIMENTS TELL US HOW PEOPLE IDENTIFY IMPOSTORS?

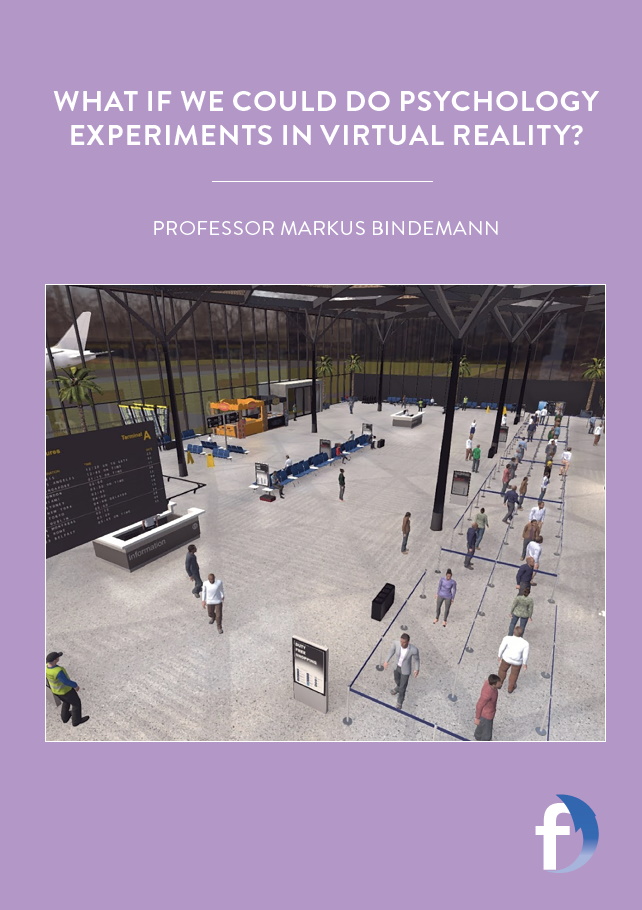

To answer this and other questions, Markus and his team built a virtual reality passport control game. They create realistic avatars of real people by using handheld scanners to generate a 3D model of a volunteer’s head. The head is then attached to an avatar body and the body rigged with a skeleton so it can move around in VR. The clothing, body size and other elements of the avatar’s appearance can be varied. Participants in the study then ‘play’ as the passport controller in an airport, checking the faces of avatars against a passport photograph as the avatars file through the control booth.

“This scenario investigates the real-world phenomenon of identity-impostors,” Markus says. “Modern passports are extremely difficult to forge but, for people with criminal intentions, one way of passing through security undetected is to utilise the identity documents of someone with a similar appearance.” The research team can investigate how different factors affect participants’ ability to accurately match faces to photographs by changing the VR scenario a little bit at a time. “We have variations of this task to understand what might impact identification accuracy at airports,” Markus explains. “For example, do agitated crowds (versus orderly queues) of waiting travellers in an airport exert time pressure on the passport controller and increase the failure to detect impostors?”

AVATARS AS A RESEARCH TOOL

As with any research method, Markus and his team have had to assess and evaluate the quality of their avatars rigorously. “We have examined how well observers can recognise avatars of people that they know, and the answer is they can recognise these as well as photographs. We have performed computations to measure how similar avatars of different people are to each other – and we found that this produces the same ‘similarity space’ as photos of the same people. And we have compared person identification of avatars in our virtual airport with established laboratory tasks that measure face identification and have found strong correspondence there.”

Developing such high-quality avatars has been challenging but will help to drive on Markus’s research for years to come. “It is complex and sophisticated technology, and we also put it to complex and sophisticated use,” he explains. “I lead a research team which works on this, so much of my role is to coordinate and make key decisions. My research assistants were completely new to this technology at the start of this project, but have learned to scan and build avatars, and to run experiments in VR in the space of a couple of years.”

For Markus and his team, developing avatars has been professionally and academically rewarding. “It has been a really fun journey of discovery,” says Markus. “Making the first 3D scans of people, for example, was hugely exciting. And it continues to be really interesting for us to see how well we can scan different people and convert these into avatars – for example, someone with dreadlocks, long curly hair, a beard or distinctive facial marks.”

WHAT’S NEXT FOR PSYCHOLOGY IN VR?

Markus’ avatars cannot yet talk, interact, or change their facial expressions. Making the simulations more sophisticated is the team’s immediate goal, with the aim of gaining a better understanding of face and person perception. This has the potential to help people with facial recognition disorders, to improve security systems, and to interpret the reliability of eyewitness testimony in court cases, among many other possible applications.

In the long term, the potential of VR for psychology and neuroscience is enormous and goes far beyond face perception or passport control. “I know psychologists who are using VR for research in forensic settings, in sports science, or in clinical settings,” says Markus. Researchers across the psychological disciplines are now carrying out experiments in VR to study, for example, how people communicate and interact with each other, how people navigate through complex environments, or to provide novel treatments for addictions or anxiety disorders.

PROFESSOR MARKUS BINDEMANN

PROFESSOR MARKUS BINDEMANN

Professor of Cognitive Psychology, University of Kent, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Cognitive psychology, Neuropsychology, Visual Perception

RESEARCH PROJECT: Investigating face perception and face-identity matching in virtual reality.

FUNDERS: Economic and Social Research Council (Grant no ES/S010181/1)

ABOUT COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY

WHAT IS COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY?

Cognitive psychology is the study of mental processes like perception, memory, creativity and problem-solving. Cognitive psychologists perform experiments with human participants to study how people think, process information, and mentally represent the outside world.

WHAT RESEARCH AREAS DOES COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY COVER?

Some major research areas in cognitive psychology include: object recognition and pattern recognition; attention; language learning and language processing; memory formation; different kinds of memory such as autobiographical memory, eyewitness memory, short-term and long-term memory, working memory, and false memory; decision-making and choice; problem-solving; reasoning and logic; knowledge representation; and judgment and categorisation.

HOW IS COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY RESEARCH USED IN PRACTICE?

Findings from cognitive psychology can be useful in clinical psychology to help people with psychological disorders, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or Alzheimer’s disease. Cognitive psychology helps define and shape therapeutic practices like cognitive behavioural therapy. Cognitive psychology is also important in the justice system when interpreting eyewitness testimony and recall of events.

EXPLORE A CAREER IN COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY

• The British Psychological Society (BPS) provides excellent information about how to become a psychologist, as well as the latest news from the world of psychology.

• Markus recommends looking at the websites of psychology departments at universities in the UK and beyond. “The best departments will have news about the latest research, websites for their staff including research interests and achievements – and, of course, that is where you can find some of the most famous psychologists in the world. Often these websites will also provide information about the exciting equipment and technologies that we use – such as VR!”

• The NHS Foundation Trust offers undergraduate internships in psychology. HM Prison & Probation Service sometimes offers trainee counselling psychologist placements.

• Graduate psychologists can seek an academic career or work in industry or the public sector in a variety of jobs. Non-academic jobs include counselling and psychotherapy, witness assessment services, occupational psychology, and forensic psychology.

• In the UK, psychologist salaries start at around £37,000 in the NHS and range up to £60,000, or higher for consultants. In the USA, the American Psychological Association reported an average salary of $90,000 for industrial and organisational psychologists in 2007. A typical salary for a post in psychology at a university is £35,000-£50,000 in the UK or $62,000 in the USA.

Markus recommends studying maths and biology in school, as well as psychology at university. He adds that psychology is a diverse field – it ranges from clinical practice to animal behaviour research – and it is a good idea to read around and try out a variety of courses to find out what appeals to you personally.

Psychology is available as a subject in GSCEs, A Levels, Scottish Highers, Advanced Placement exams and International Baccalaureate diplomas.

A bachelor’s or MSc degree in psychology or a sub-field like developmental psychology or neuropsychology is a solid foundation for a career as a psychologist.

HOW DID MARKUS BECOME A COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGIST?

WHAT WERE YOUR INTERESTS AS A YOUNGSTER?

I was into music and sports, nothing out of the ordinary!

WHAT INSPIRED YOU TO BECOME A COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGIST?

I decided to study psychology at university without really knowing what the subject was. Many people just connect the subject with clinical psychology, and I was one of those people too. But I had fantastic lecturers at university who introduced me to many exciting areas of psychology – such as comparative psychology and animal behaviour, vision science, and face perception.

WHAT HAS MADE YOU SUCCESSFUL AS A SCIENTIST?

Scientists work a lot and you need intrinsic motivation to keep going. I didn’t realise that I had this motivation until I reached my 20s – so don’t panic if your motivation to study has not peaked yet!

WHAT DO YOU FIND REWARDING ABOUT WORK IN YOUR FIELD?

Working at the forefront of knowledge is a serious occupation, but it’s also fun. As a scientist, my job is to recognise that there is a question that we don’t know the answer to yet, that the question is worth asking, and then to find a way to work out the correct answer by using the scientific method. It’s a creative and stimulating process. Person identification is also an interesting research field because it’s such a big part of what we do in daily life. Understanding how we identify the people around us and interact with others runs through everything we do.

HOW DO YOU GET THROUGH TOUGH SPOTS IN YOUR WORK?

Persistence is key, but so is acceptance that it takes time to figure out complex problems. I find it important to read and write to clarify my thinking and my ideas at points when I get stuck. Another way of overcoming obstacles is to work collaboratively – to pool expertise and intellect to work on a problem together.

WHAT ARE YOUR PROUDEST CAREER ACHIEVEMENTS?

My proudest achievement has always been to help others succeed. I have taught people from many different walks of life and seen them blossom into competent psychologists. It is particularly rewarding when you work with someone over several years and can see how they develop from an enthusiastic student to an independent researcher, capable of forging their own career.

MARKUS’ TOP TIPS

01 Follow your own interests and develop them. Read as much as you can and read carefully, so you can grasp content fully and make connections between different sources.

02 Take opportunities when they come your way. Don’t limit yourself – give things a go. It really is better to have tried and failed than never to have tried at all.

03 Appreciate that it takes a long time to become an expert at anything. It will take many years, so make sure you enjoy the journey.

Write it in the comments box below and Markus will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

It was too good

Good