What if we could understand how and why languages evolve?

There are over 7,000 languages spoken across the world, but how and why did these languages evolve? To answer this question, Dr Jenny Culbertson of the University of Edinburgh in the UK is investigating our capacity to learn artificial languages – and her findings could help unlock the secrets of this uniquely human ability

TALK LIKE A LINGUIST

LINGUISTICS – the scientific study of language, including how we learn and use sounds, words and phrases to communicate

CULTURE – a broad term describing the habits of large groups of people living in the same area, which are passed on to new generations through learning and socialising

PSYCHOLOGY – the study of how our minds work, and how processes in our brains and bodies influence our thoughts, feelings and behaviours

LEARNING BIAS – in the case of linguistics, a learning bias describes a preference we have for certain linguistic patterns or behaviours, regardless of our experience with language

WORD ORDER – how words in a phrase are ordered, e.g., ‘these two cups’ has the order Demonstrative Numeral Noun

DEMONSTRATIVE – a class of words including ‘this’, ‘that’, ‘these’, ‘those’ in English, used to indicate items in space or time

SIGN LANGUAGES – languages that use visual means to communicate, including hand gestures and facial expressions, used mainly by people who are Deaf or have hearing impairments

Language – be it spoken or signed – is the most important tool we have for sharing our thoughts, feelings and ideas. As you read this article, for example, you are using your knowledge of the English language to learn more about linguistics! But English is just one of over 7,000 languages spoken all over the world – and among the 8 billion people who speak these 7,000 languages, there is an incredibly diverse range of cultures. Over tens of thousands of years, these disparate groups have developed their own languages to make sense of the world around them.

“In Northern Paiute, an indigenous language of the western US, words for siblings like ‘brother’ and ‘sister’ have different versions that specify whether they are older or younger,” says Dr Jenny Culbertson, a linguist and Director of the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Language Evolution. “Languages spoken on islands and atolls, like Marshallese, use words like ‘oceanward’ and ‘lagoonward’ to navigate instead of ‘north’ and ‘south’.”

This linguistic diversity has its roots in cultural diversity: languages evolve from a need for people to express ideas that their particular culture considers important. However, researchers like Jenny propose that our language is also shaped by how we, as humans, learn, in a way that does not depend on culture.

CULTURAL EXPERIENCES AND PATTERNS IN THE MIND

To express this idea, linguists use the phrase ‘learning bias’. A learning bias describes a preference we have for certain linguistic patterns or behaviours that does not come from the experience with language that we have had. If our language knowledge came purely from experience, as some psychologists believe, Jenny argues that we would simply mimic the language of the people around us as we grow up, and speak like our parents.

As Jenny explains, this does not capture some of the most important things we know about language. “Even as toddlers, we create new words and sentences we’ve not heard before,” she says. “Many linguists argue that this reveals a learning bias to reuse and recombine sounds and words in systematic ways.” In other words, no matter our culture, the language we use reflects certain patterns and behaviours that come from the way our human minds work. Amazingly, we can also see this idea in action in the similar patterns of words found across otherwise very different languages.

WHICH TWO BLACK CATS?

By studying similarities and differences in the sentence structures used in different languages, Jenny can explore how learning biases shape language. Take the English phrase, ‘these two black cats’. In Thai, the phrase would be ‘maw dả s̄xng tạw nī̂’, or literally ‘cats black two these’. In Basque, a language spoken in Spain, it would be ‘bi katu beltz hauek’, or ‘two cats black these’. Although the words are ordered differently in each case, it turns out that all three languages actually follow a very common pattern: when the adjective, numeral or demonstrative are on the same side of the noun, adjectives come closest to the noun, demonstratives (words such as this, that or those) are farthest away, and numerals fall in between. Word orders that do not follow this pattern, like ‘black two these cats’, ‘cats these two black’, or ‘black cats these two’ are far less likely to be used in a language. According to Jenny, this hints at what she calls ‘universal’ learning biases: language patterns that all humans prefer, no matter their cultural background.

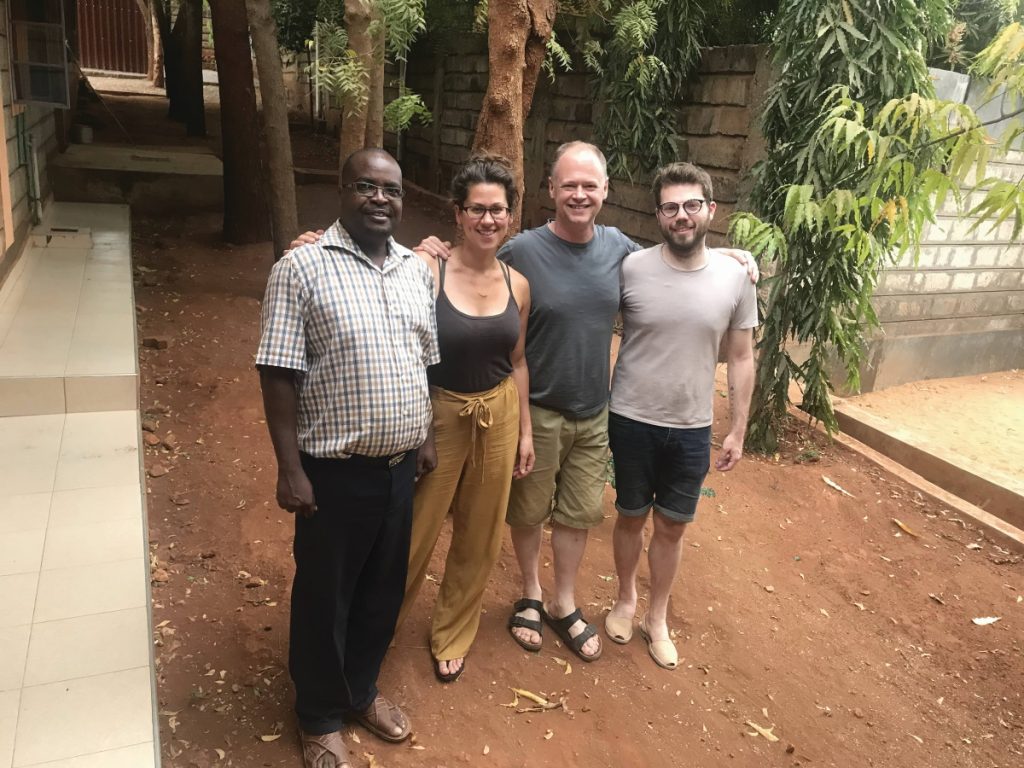

A TRIP TO KENYA

A key part of Jenny’s research is to gather evidence for universal learning biases in controlled experiments. To do this, Jenny and her team travelled to Kenya to work with people who speak Kîîtharaka – a language spoken in a rural area around 100 miles from the Kenyan capital of Nairobi. Today, all children in Kenya must learn English in school. However, many people in their 60s and 70s went to school before this law was passed, and so they are ‘monolingual’, meaning they only speak one language – in this case, Kiitharaka. Because of this, they are not familiar with the sentence structures used in other languages.

As Jenny describes, her team’s mission was no simple task. “As you can imagine, recruiting monolingual Kîîtharaka-speaking participants is very complicated,” she says. “In our study, we worked with a collaborator who is a member of that community and can travel around to visit the Kîîtharaka speakers.” Jenny’s collaborators have documented that in Kîîtharaka ‘these two black cats’ is ‘mbaka ino njiru ciîrî’, literally ‘cats these two black’. This is a rare order where adjectives, instead of being close to the noun, are farthest away, and demonstratives, instead of being farthest from the noun, are closest. Jenny explains, “If we can show that Kîîtharaka speakers, despite experience only with this kind of rare pattern, find it easier to learn a language with a more common pattern, that would be very strong evidence for a universal learning bias.”

MAKING UP NEW LANGUAGES

In her search for evidence of universal learning biases, Jenny constructs artificial languages, and looks at how they are learned. To create them, she constructs sentences of made-up words using some linguistic rules or patterns, like the ones used in Kîîtharaka, English or Thai. She then recruits people to find out how easy these artificial languages are to learn by speakers of other languages. “I’ve made artificial languages with words and grammar to describe cute animals, weird insects, aliens, chefs punching burglars and groups of friends eating bananas!” Jenny says. “We try to make it fun for people to learn.”

So far, Jenny’s research has included working with people who speak English, Thai and Hebrew. Her research on Kîîtharaka is the latest ongoing project. Jenny’s aim is to find out how easy it is for them to learn each other’s sentence structures when expressed in an artificial language that Jenny’s team has made up. In turn, she will uncover whether certain linguistic patterns are learned more easily. “If the patterns we find commonly among the world’s 7,000 languages are easy to learn, while very rare patterns are hard, this would provide key evidence that universal learning biases, shared by all humans, shape the evolution of language.”

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM159

TALK LIKE A LINGUIST

LINGUISTICS – the scientific study of language, including how we learn and use sounds, words and phrases to communicate

CULTURE – a broad term describing the habits of large groups of people living in the same area, which are passed on to new generations through learning and socialising

PSYCHOLOGY – the study of how our minds work, and how processes in our brains and bodies influence our thoughts, feelings and behaviours

LEARNING BIAS – in the case of linguistics, a learning bias describes a preference we have for certain linguistic patterns or behaviours, regardless of our experience with language

WORD ORDER – how words in a phrase are ordered, e.g., ‘these two cups’ has the order Demonstrative Numeral Noun

DEMONSTRATIVE – a class of words including ‘this’, ‘that’, ‘these’, ‘those’ in English, used to indicate items in space or time

SIGN LANGUAGES – languages that use visual means to communicate, including hand gestures and facial expressions, used mainly by people who are Deaf or have hearing impairments

“In Northern Paiute, an indigenous language of the western US, words for siblings like ‘brother’ and ‘sister’ have different versions that specify whether they are older or younger,” says Dr Jenny Culbertson, a linguist and Director of the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Language Evolution. “Languages spoken on islands and atolls, like Marshallese, use words like ‘oceanward’ and ‘lagoonward’ to navigate instead of ‘north’ and ‘south’.”

This linguistic diversity has its roots in cultural diversity: languages evolve from a need for people to express ideas that their particular culture considers important. However, researchers like Jenny propose that our language is also shaped by how we, as humans, learn, in a way that does not depend on culture.

CULTURAL EXPERIENCES AND PATTERNS IN THE MIND

To express this idea, linguists use the phrase ‘learning bias’. A learning bias describes a preference we have for certain linguistic patterns or behaviours that does not come from the experience with language that we have had. If our language knowledge came purely from experience, as some psychologists believe, Jenny argues that we would simply mimic the language of the people around us as we grow up, and speak like our parents.

As Jenny explains, this does not capture some of the most important things we know about language. “Even as toddlers, we create new words and sentences we’ve not heard before,” she says. “Many linguists argue that this reveals

a learning bias to reuse and recombine sounds and words in systematic ways.” In other words, no matter our culture, the language we use reflects certain patterns and behaviours that come from the way our human minds work. Amazingly, we can also see this idea in action in the similar patterns of words found across otherwise very different languages.

WHICH TWO BLACK CATS?

By studying similarities and differences in the sentence structures used in different languages, Jenny can explore how learning biases shape language. Take the English phrase, ‘these two black cats’. In Thai, the phrase would be ‘maw dả s̄xng tạw nī̂’, or literally ‘cats black two these’. In Basque, a language spoken in Spain, it would be ‘bi katu beltz hauek’, or ‘two cats black these’. Although the words are ordered differently in each case, it turns out that all three languages actually follow a very common pattern: when the adjective, numeral or demonstrative are on the same side of the noun, adjectives come closest to the noun, demonstratives (words such as this, that or those) are farthest away, and numerals fall in between. Word orders that do not follow this pattern, like ‘black two these cats’, ‘cats these two black’, or ‘black cats these two’ are far less likely to be used in a language. According to Jenny, this hints at what she calls ‘universal’ learning biases: language patterns that all humans prefer, no matter their cultural background.

A TRIP TO KENYA

A key part of Jenny’s research is to gather evidence for universal learning biases in controlled experiments. To do this, Jenny and her team travelled to Kenya to work with people who speak Kîîtharaka – a language spoken in a rural area around 100 miles from the Kenyan capital of Nairobi. Today, all children in Kenya must learn English in school. However, many people in their 60s and 70s went to school before this law was passed, and so they are ‘monolingual’, meaning they only speak one language – in this case, Kiitharaka. Because of this, they are not familiar with the sentence structures used in other languages.

As Jenny describes, her team’s mission was no simple task. “As you can imagine, recruiting monolingual Kîîtharaka-speaking participants is very complicated,” she says. “In our study, we worked with a collaborator who is a member of that community and can travel around to visit the Kîîtharaka speakers.” Jenny’s collaborators have documented that in Kîîtharaka ‘these two black cats’ is ‘mbaka ino njiru ciîrî’, literally ‘cats these two black’. This is a rare order where adjectives, instead of being close to the noun, are farthest away, and demonstratives, instead of being farthest from the noun, are closest. Jenny explains, “If we can show that Kîîtharaka speakers, despite experience only with this kind of rare pattern, find it easier to learn a language with a more common pattern, that would be very strong evidence for a universal learning bias.”

MAKING UP NEW LANGUAGES

In her search for evidence of universal learning biases, Jenny constructs artificial languages, and looks at how they are learned. To create them, she constructs sentences of made-up words using some linguistic rules or patterns, like the ones used in Kîîtharaka, English or Thai. She then recruits people to find out how easy these artificial languages are to learn by speakers of other languages. “I’ve made artificial languages with words and grammar to describe cute animals, weird insects, aliens, chefs punching burglars and groups of friends eating bananas!” Jenny says. “We try to make it fun for people to learn.”

So far, Jenny’s research has included working with people who speak English, Thai and Hebrew. Her research on Kîîtharaka is the latest ongoing project. Jenny’s aim is to find out how easy it is for them to learn each other’s sentence structures when expressed in an artificial language that Jenny’s team has made up. In turn, she will uncover whether certain linguistic patterns are learned more easily. “If the patterns we find commonly among the world’s 7,000 languages are easy to learn, while very rare patterns are hard, this would provide key evidence that universal learning biases, shared by all humans, shape the evolution of language.”

DR JENNY CULBERTSON

DR JENNY CULBERTSON

Director of the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Language Evolution

The University of Edinburgh, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Linguistics

RESEARCH PROJECT: Jenny studies the similarities and differences between the linguistic patterns used by languages around the world. Through the use of artificial languages, she is studying whether these patterns emerge because of local cultures or are more influenced by universal properties of the human mind.

FUNDERS: UK Research and Innovation; European Research Council

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant number ES/N018389/1), and by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 757643).

DR JENNY CULBERTSON

DR JENNY CULBERTSON

Director of the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Language Evolution

The University of Edinburgh, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Linguistics

RESEARCH PROJECT: Jenny studies the similarities and differences between the linguistic patterns used by languages around the world. Through the use of artificial languages, she is studying whether these patterns emerge because of local cultures or are more influenced by universal properties of the human mind.

FUNDERS: UK Research and Innovation; European Research Council

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant number ES/N018389/1), and by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 757643).

ABOUT THE EVOLUTION OF LANGUAGE

The society we have built for ourselves today would have been impossible without language. While many animals can talk to each other using noises, movements and even smells, none of their communication systems are nearly as rich or complex as the languages we use. For linguists, this creates two particularly important questions: how did language come to be as rich and complex as it is? And secondly, how did human language evolve from the kinds of communication systems used by other animals?

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM LANGUAGE SYSTEMS CREATED BY DEAF COMMUNITIES?

Some of the most exciting recent discoveries have come from studying newly emerging sign languages. “These are visual languages created by Deaf communities where there is no existing common sign language they can use. In other words, they have to create a language wholesale,” explains Jenny. Her team has recreated these processes in the lab, by asking hearing people with no previous knowledge of a sign language to make up their own hand gestures for communicating ideas, and then passing them on to a new set of people to learn and use in turn.

WHAT DID THIS TELL US ABOUT HOW LANGUAGE BECAME SO COMPLEX?

As newly created hand gestures were used and then passed from one ‘generation’ of participants to the next, orderly linguistic patterns emerged that were similar to those developed by Deaf communities. This suggests that both the complexity and the regularities we see in more established sign and spoken languages have developed over many years of people learning from past generations and then using what they have learned to communicate. If these ideas are correct, they could go a long way to explaining how languages have developed over time to become both rich and complex but also learnable.

WHAT ABOUT THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN OUR LANGUAGE AND ANIMAL COMMUNICATIONS?

Like humans, animals can share information with each other about the world around them. For example, many species of monkeys living in the rainforest use a distinct set of ‘alarm calls’ and ‘food calls’. “Monkeys are closely related to us, so it’s very interesting that they have this ability,” says Jenny, “but their repertoire of calls is small, say 15 calls per species, compared to the 10-15,000 words that a typical 10-year-old knows.” Other animal species, like songbirds and dolphins, can learn to copy complex sounds, and even sometimes create new sound combinations. But as far as we know, these sounds do not have specific meanings. “Humans seem to be unique in having both the ability to learn complex sounds, and the ability to use them to share meaningful information about the world around us.”

EXPLORE A CAREER IN LINGUISTICS

• Jenny recommends checking out The Linguistics Society of America (www.linguisticsociety.org), which has a section called ‘What is Linguistics?’. Here, you can find information about studying and working in linguistics.

• “Linguistics graduates are well-equipped to undertake careers ranging from marketing and publishing to speech and language therapy,” says Prospects, which lists job options and potential employers: www.prospects.ac.uk/careers-advice/what-can-i-dowith-my-degree/linguistics

PATHWAY FROM SCHOOL TO LINGUISTICS

Jenny recommends studying psychology and foreign languages at school, as they often include elements of linguistics. Many universities worldwide now offer dedicated courses in linguistics and the psychology of language.

HOW DID JENNY BECOME A LINGUIST?

WHAT DID YOU WANT TO BE WHEN YOU WERE YOUNGER?

I’ve wanted to be an academic for an embarrassingly long time, since early high school!

WHAT INSPIRED YOU TO STUDY LINGUISTICS?

I was studying Classics (Ancient Greek and Latin) when I first went to university, but I knew it wasn’t quite the right thing for me. At some point, I did an independent study class (I was very lucky because it was just me and a professor) on how Latin changed into the Romance languages like French, Spanish and Italian. I was super fascinated, and that led me to linguistics.

YOU HAVE A BA IN LINGUISTICS AND CLASSICS, AND AN MA AND PHD IN COGNITIVE SCIENCE. WHY DID YOU MAKE THE MOVE FROM LINGUISTICS TO COGNITIVE SCIENCE?

I had no idea about cognitive science until I applied to graduate school at Johns Hopkins University in the US. I remember that as soon as I got there and started talking to people, I just thought, yes, this is it! Cognitive science is an interdisciplinary field that is focused on the study of the human mind and how it represents knowledge. That includes perspectives from linguistics, psychology, computer science and philosophy. So, it’s much broader, and really lets you see the big picture and think about language as just one (very cool) part of human cognition.

DO YOU LOVE LEARNING LANGUAGES?

I do love learning languages, but sadly, aside from English and French, I don’t speak any others fluently. That’s partly because of my focus on languages like Ancient Greek, Latin and Sanskrit, which aren’t spoken anymore, and partly because the type of linguistics I do is focused less on particular languages and more on language, in general. But many linguists are amazing speakers of multiple languages!

WHAT SHOULD WE ALL KNOW ABOUT LEARNING LANGUAGES?

It’s hard! And we are much better at it as children. But recent research suggests that the window for native-like language learning might be wider than we thought – up to the age of 20. So, it’s not too late to start. Most people in the world speak more than one language.

JENNY’S TOP TIPS

01 These days, a lot of linguistics involves maths and computer programming. These are great skills to have for almost any career, so start early!

02 I would also highly recommend seeking out people who work in linguistics in your area to see whether they have any job opportunities available. That’s how I really got into linguistics, by working in a language acquisition lab.

Do you have a question for Jenny?

Write it in the comments box below and Jenny will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

Excellent article all around, Jenny. Totally down-to-earth talk but all the right ideas well expressed! Not in the least cringy (which I take to mean cringe-worthy?). Thanks for the shout-out to JHU Cogsci! And of course I love your top tip too.

Kind of you to accept to reply to crazy comments from crazy unknown people, like this one. Have you gotten many?

Hi Paul,

Thanks for having a look, and sorry for taking ages to respond (there is no mechanism to alert me other than the kind folks at Futurum, who’ve just told me this was here). No comments yet other than yours, but happy to take them. And if anyone comes here and would rather ask me something privately, please do! Just google me and you can find my contact info.

-Jenny