Why do people working in STEM stay in their jobs – and why should we care?

STEM education creates critical thinkers, improves levels of science literacy, and helps to create the next generation of innovators. Industries and occupations with a particularly strong focus in STEM areas have been shown to generate many of the innovations that lead to increased productivity in the workforce.

For these reasons, having a healthy amount of scientific and technical services professionals as part of a workforce is highly desirable. However, mounting evidence shows that an increasing number of these professionals are switching to non-STEM industries. Researchers around the world are investigating why this might be so, their aim being to reverse the situation.

Dr Kohyar Kiazad, who is based at Monash University, is one such researcher with a particular focus on Australia’s STEM workforce. He is currently working on a three-year, multi-university project investigating how to strengthen Australia’s STEM workforce and retain key staff. Interestingly, Kohyar’s research looks at what makes professionals stay in their jobs, rather than what makes them leave.

WHAT IS JOB EMBEDDEDNESS?

Job embeddedness is a term that refers to the totality of forces that keep people in their employing organisation. The theory of job embeddedness says that the forces that embed people can exist in an individual’s organisation or the community where they live. “Community influences matter if changing jobs means having to relocate. More specifically, people stay because of their valued connections to other people or groups at work or in their community,” explains Kohyar. “They stay because of their comfort and compatibility with their workplace or living environment, and they stay to avoid losing material or psychological benefits linked to their employment or place or residence.”

Almost two decades of empirical research (research based on evidence that has been acquired from direct and indirect observation or experience) confirms the validity of job embeddedness as a theory over and above more “traditional” reasons, such as job satisfaction and commitment to an organisation.

WHY FOCUS ON THE REASONS PEOPLE STAY IN THEIR JOBS AS OPPOSED TO WHAT MAKES THEM LEAVE?

The psychology of staying in a job recognises that the reasons why employees stay are not necessarily mirror opposites of the reasons for leaving. There are different underlying motives behind a decision to stay or leave – an individual might stay because they have strong ties to colleagues, but may leave because of pay dissatisfaction.

Kohyar’s research programme therefore focuses on uncovering the variety of reasons why STEM professionals stay, as an important first step towards the development of interventions focused on retaining high-performing STEM professionals.

WHAT ARE THE WORK AND NON-WORK FACTORS THAT KEEP PEOPLE IN THEIR STEM JOBS?

The factors that keep people in their jobs can exist on or off the job. For example, Terry Mitchell – one of the co-founders of job embeddedness theory – once noted that he stayed at the Foster School of Business, University of Washington, because it was comfortable to be near the city of Seattle, as well as the fact that he was a Seattle Seahawk season ticket holder!

It is also possible that organisational and community factors offer benefits to employees’ families, which embeds employees indirectly by embedding their families; employees might stay in an organisation because their families want to maintain access to corporate benefits or social ties to friends in the community.

Ultimately, job embeddedness theory encapsulates an array of work and non-work factors that promote workplace retention, and Kohyar and his team are investigating these influences in the STEM context. This is important, because their findings could help governments and organisations worldwide launch new initiatives that encourage a flourishing STEM workforce.

- Intrinsic motivation and passion appear to be the fundamental drivers of staying and succeeding in STEM fields

- Money is NOT a strong motivator for entering STEM fields or staying in those fields

- Lack of employment opportunities, job security, and passion to pursue scientific work are strong drivers of leaving, or not entering STEMemployment upon graduation

- Some consider the STEM career pathway to be too uncertain, unpredictable and with strong opportunity costs. Opportunity costs are the benefitsan individual might miss out on when choosing one alternative over another.

- Family influence (i.e. parents, siblings) does not seem to be important to peoples’ decisions to enter STEM education

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM28

STEM education creates critical thinkers, improves levels of science literacy, and helps to create the next generation of innovators. Industries and occupations with a particularly strong focus in STEM areas have been shown to generate many of the innovations that lead to increased productivity in the workforce.

For these reasons, having a healthy amount of scientific and technical services professionals as part of a workforce is highly desirable. However, mounting evidence shows that an increasing number of these professionals are switching to non-STEM industries. Researchers around the world are investigating why this might be so, their aim being to reverse the situation.

Dr Kohyar Kiazad, who is based at Monash University, is one such researcher with a particular focus on Australia’s STEM workforce. He is currently working on a three-year, multi-university project investigating how to strengthen Australia’s STEM workforce and retain key staff. Interestingly, Kohyar’s research looks at what makes professionals stay in their jobs, rather than what makes them leave.

WHAT IS JOB EMBEDDEDNESS?

Job embeddedness is a term that refers to the totality of forces that keep people in their employing organisation. The theory of job embeddedness says that the forces that embed people can exist in an individual’s organisation or the community where they live. “Community influences matter if changing jobs means having to relocate. More specifically, people stay because of their valued connections to other people or groups at work or in their community,” explains Kohyar. “They stay because of their comfort and compatibility with their workplace or living environment, and they stay to avoid losing material or psychological benefits linked to their employment or place or residence.”

Almost two decades of empirical research (research based on evidence that has been acquired from direct and indirect observation or experience) confirms the validity of job embeddedness as a theory over and above more “traditional” reasons, such as job satisfaction and commitment to an organisation.

WHY FOCUS ON THE REASONS PEOPLE STAY IN THEIR JOBS AS OPPOSED TO WHAT MAKES THEM LEAVE?

The psychology of staying in a job recognises that the reasons why employees stay are not necessarily mirror opposites of the reasons for leaving. There are different underlying motives behind a decision to stay or leave – an individual might stay because they have strong ties to colleagues, but may leave because of pay dissatisfaction.

Kohyar’s research programme therefore focuses on uncovering the variety of reasons why STEM professionals stay, as an important first step towards the development of interventions focused on retaining high-performing STEM professionals.

WHAT ARE THE WORK AND NON-WORK FACTORS THAT KEEP PEOPLE IN THEIR STEM JOBS?

The factors that keep people in their jobs can exist on or off the job. For example, Terry Mitchell – one of the co-founders of job embeddedness theory – once noted that he stayed at the Foster School of Business, University of Washington, because it was comfortable to be near the city of Seattle, as well as the fact that he was a Seattle Seahawk season ticket holder!

It is also possible that organisational and community factors offer benefits to employees’ families, which embeds employees indirectly by embedding their families; employees might stay in an organisation because their families want to maintain access to corporate benefits or social ties to friends in the community.

Ultimately, job embeddedness theory encapsulates an array of work and non-work factors that promote workplace retention, and Kohyar and his team are investigating these influences in the STEM context. This is important, because their findings could help governments and organisations worldwide launch new initiatives that encourage a flourishing STEM workforce.

- Intrinsic motivation and passion appear to be the fundamental drivers of staying and succeeding in STEM fields

- Money is NOT a strong motivator for entering STEM fields or staying in those fields

- Lack of employment opportunities, job security, and passion to pursue scientific work are strong drivers of leaving, or not entering STEMemployment upon graduation

- Some consider the STEM career pathway to be too uncertain, unpredictable and with strong opportunity costs. Opportunity costs are the benefitsan individual might miss out on when choosing one alternative over another.

- Family influence (i.e. parents, siblings) does not seem to be important to peoples’ decisions to enter STEM education

DR KOHYAR KIAZAD

DR KOHYAR KIAZADAssociate Professor

Centre for Global Business, Monash Business School, Monash University, Australia

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Organisational Behaviour

RESEARCH PROJECT: Kohyar and his colleagues are currently working on a three-year multi-university project that investigates how to strengthen Australia’s STEM workforce and retain key staff.

FUNDER: Australian Research Council, Discovery Scheme, 2017

DR KOHYAR KIAZAD

DR KOHYAR KIAZADAssociate Professor

Centre for Global Business, Monash Business School, Monash University, Australia

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Organisational Behaviour

RESEARCH PROJECT: Kohyar and his colleagues are currently working on a three-year multi-university project that investigates how to strengthen Australia’s STEM workforce and retain key staff.

FUNDER: Australian Research Council, Discovery Scheme, 2017

Organisational behaviour is the academic study of the ways people act within organisational groups, the interface between human behaviour and the organisation, and the organisation itself. It is a multidisciplinary subject that is influenced by developments in a range of fields, including sociology, psychology, economics and engineering.

WHY DO PEOPLE STUDY ORGANISATIONAL BEHAVIOUR?

There are many reasons why researchers are interested in organisational behaviour, but some of the main areas of focus are centred on improving job performance, increasing job satisfaction, promoting innovation and encouraging leadership. Each of these factors generate their own recommended actions, such as reorganising departments, modifying pay structures, or changing the methods that evaluate workers’ performance.

HOW DID THE STUDY OF ORGANISATIONAL BEHAVIOUR COME ABOUT?

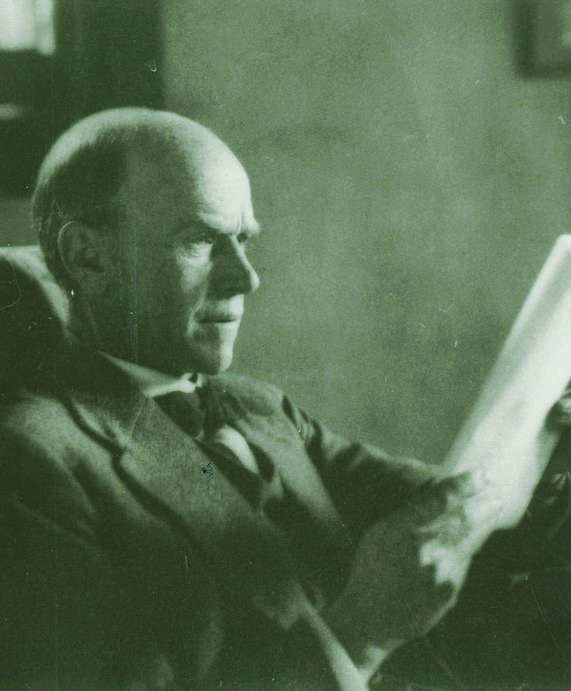

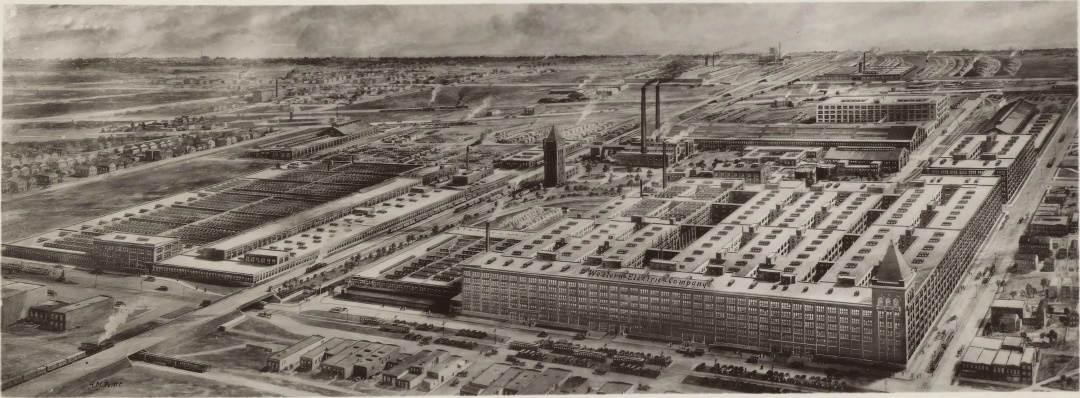

In the late 1920s, the Western Electric Company launched a series of studies that looked at the behaviour of its workers at its Hawthorne Work Plant in Illinois, USA. The Hawthorne Studies – which have since become famous – were conducted by Elton Mayo and Fritz Roethlisberger and were part of a refocus on managerial strategy, which incorporated the socio-psychological aspects of human behaviour in organisations.

The studies originally looked into whether certain environmental conditions – such as improved lighting – had an impact on worker performance. The results were surprising: Mayo and Roethlisberger found that workers were more responsive to social factors, such as who they worked with and whether their manager was interested in their work. As a result, motivation became a focal point in organisational behaviour research.

This video from the AT&T archives contains interviews with individuals who participated in the Hawthorne Studies and gives additional insight into how the studies were conducted and how they shaped employers’ views on worker motivation.

WHAT ARE HIGH PERFORMANCE WORK PRACTICES?

High performance work practices (HPWPs) refer to human resource management activities that organisations use to achieve their goals. Such practices can improve an organisation’s performance by enhancing employees’ knowledge, skills and abilities, their motivation to perform, and their opportunities to contribute and participate in decision making. Kohyar and his team believe that three types of HPWPs can embed STEM professionals in their job, organisation and occupation: skill-enhancing HPWPs, opportunity-enhancing HPWPs, and motivation-enhancing HPWPs.

Skill-enhancing HPWPs, such as training and tuition reimbursement, focus on increasing employees’ transferable knowledge, skills and abilities. Such practices can help retain employees in STEM occupations by building their professional networks, augmenting their specialised skills, and producing human capital investments that would be forfeited by leaving STEM fields. Human capital can be defined as the skills, knowledge and experience a person or group of people has.

Opportunity-enhancing HPWPs focus on empowering STEM professionals with expanded decision-making authority, autonomy, and greater involvement in organisational/research centre matters. Such practices should bolster their retention by encouraging extra-unit collaborations, satisfying scientists’ competence and autonomy needs, and providing decision-making involvement and organisation-specific know-how.

Motivation-enhancing HPWPs direct STEM workers’ efforts toward superior work performance. Practices such as regular performance feedback and targeted performance incentives should strengthen STEM workers’ links with job-specific advice networks, job demands and competitive compensation.

YOU HAVE A PHD IN ORGANISATIONAL BEHAVIOUR. COULD YOU GIVE US A POTTED HISTORY OF YOUR EDUCATIONAL EXPERIENCE, STARTING WITH HIGH SCHOOL?

I graduated from high school in 1997 (while living in Brisbane). At the time I thought I wanted to become a lawyer, but unfortunately (or maybe fortunately), I didn’t meet the university entry score to pursue law. So, I enrolled in an arts degree, double majoring in psychology (thinking I would upgrade to law after one year). But I found psychology super interesting and engaging. Before long, I was graduating with an Honours degree in psychology (University of Queensland). The Honours degree gave me my first exposure to the research process and I loved it. My supervisor at the time (Simon Restubog, who is a collaborator in this research project!) encouraged me to pursue a PhD, so I moved to Melbourne (mostly because I thought living in Melbourne would be cool) and I obtained my PhD in organisational behaviour from the University of Melbourne in 2010.

HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE YOURSELF AND ARE THESE TRAITS USEFUL FOR A RESEARCHER IN ORGANISATIONAL BEHAVIOUR?

I would consider myself highly introverted – I love my work but not more than I love spending time with my son. I only work on projects I genuinely like and with people I like, and I’m unwilling to let my co-authors down. I care more about the quality of my research as opposed to the quantity of my outputs and always try to produce my best possible work. However, I’m not very efficient because I will spend as long as it takes to ensure that what I write is exactly how I want it to be. I’m not sure if these traits are useful for organisational behaviour researchers in general, but this is how I am and I’m happy with it.

ONE OF YOUR FOCUSES IS ON EMBEDDEDNESS. WHAT HAS KEPT YOU IN YOUR JOB?

For one thing, this job allows me to continuously learn, and I love learning. I get to learn as much as I want about whatever I want. I also really enjoy the research process – even with all the challenges it brings. I especially appreciate having the freedom to work on ideas that genuinely interest me. I love the freedom and autonomy that an academic career provides (I would really struggle in a job that didn’t provide this level of autonomy and freedom).

HOW PASSIONATE ARE YOU ABOUT JOB EMBEDDEDNESS IN STEM?

I only pursue research on topics I care about or find intellectually stimulating. Applying job embeddedness theory to tackle an important real-world issue, such as significant attrition in STEM, is something I genuinely care about. It’s very fulfilling to see the practical value of theoretical concepts!

FINALLY, CAN YOU TELL US ONE FUN FACT ABOUT YOURSELF?

When I’m not spending time with my son, I’m mostly training in Brazilian jiu-jitsu.

THOMAS LEE

THOMAS LEE

Role: Partner Investigator

Title: Hughes M. Blake Professor of Management in the Department of Management & Organization in the Foster School of Business, University of Washington, USA.

Fun fact: Tom played “scrum half” on the junior varsity rugby team during his sophomore year (1972-73) at the University of California, Berkeley. Sadly, he never made the varsity.

SIMON LLOYD D. RESTUBOG

SIMON LLOYD D. RESTUBOG

Role: Chief Investigator

Title: Professor of Labor and Employment Relations in the School of Employment and Labor Relations, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, USA.

Fun fact: Before joining academia, Simon spent time in a Christian monastery.

BROOKS HOLTOM

BROOKS HOLTOM

Role: Partner Investigator

Title: Professor of Management in the McDonough School of Business, Georgetown University, USA.

Fun fact: Brooks has climbed the highest active volcanoes in the US and in South America.

PETER HOM

PETER HOM

Role: Partner Investigator

Title: Professor of Management in the Department of Management, Arizona State University, USA.

Fun fact: Peter used to work in a college radio station, where he hosted a folk music show and later interviewed various political activists at the time.

ALESSANDRA CAPEZIO

ALESSANDRA CAPEZIO

Role: Chief Investigator

Title: Associate Professor of Management and Organizational Behavior in the Research School of Management, Australian National University, Australia.

Fun fact: Alessandra used to be in a rock band, and is a self-identified “mod” or mod-century modern enthusiast.