Why do some chemical reactions oscillate?

A chance discovery of an unusual oscillatory reaction by a Russian chemist nearly 70 years ago has paved the way for some potentially exciting, modern applications. Professor Irving Epstein at Brandeis University, USA, is investigating the mysteries behind this very special chemical reaction

TALK LIKE A CHEMIST

LINEAR PROCESS – a process in which the observed value is linearly proportional to the input variable

NONLINEAR PROCESS – a process in which the observed value is not linearly scaled to the input variable

VARIABLE – a quantity that can take on different values at different times or positions

OBSERVABLE – what you measure or see in a process

OSCILLATION – a periodic change, like the tides in the sea or the motion of a pendulum

CHAOS – non-periodic, deterministic change, like the weather

Sometimes life is simple. You push an object, it moves. You push the same object twice as hard; it moves twice as fast. If you were to record the forces and speeds in an experiment, you would expect to see that the greater the force on the object, the faster it moves. If the speed of the object always increases in direct proportion to the force on it, this is known as a linear relationship. However, as Professor Irving Epstein and his team at Brandeis University in the US have shown, not everything is that simple – particularly in chemistry. Irv heads the Nonlinear Chemical Dynamics Group which investigates systems that show much more complex, nonlinear behaviour.

So, what does it mean when a process is nonlinear? In a linear process, the outcome is linearly proportional to the input variable. Let’s take the earlier example: If you pushed a box with twice as much force and the speed doubled, and then with four times as much force, and the speed quadrupled, this would be an example of a linear process. If you think of this process in terms of a graph, plotting a graph of input force against output speed would produce a straight line. But if, when you doubled the amount of force used, the speed increased by four times the amount, this would be an example of a nonlinear process. The ratio of speed to force is not constant, producing a nonlinear relationship, and plotting a graph of output speed against input force would produce a curve.

Nonlinear systems can be challenging to understand and sometimes show some unusual phenomena, including oscillatory behaviour of the observable process. Irv explains, “Common examples of nonlinearity beyond chemistry are population oscillations in a predator-prey system, like foxes and rabbits; the apparently (but not truly) random times at which a drop of water falls from a dripping faucet; the growth of the striped pattern on a tiger’s coat; the fractal structure of a snowflake.” While these phenomena are familiar to us, the nonlinear processes responsible for them are in fact difficult to predict and understand.

HOW DOES NONLINEARITY RELATE TO CHEMISTRY?

Oscillatory reactions are an example of nonlinear processes that occur in chemistry. These were originally discovered by accident by a Russian scientist called Boris Belousov in the 1950s. “Belousov was actually looking for something else,” says Irv. “While conducting his experiment, he happened to notice that the concentration of yellow ceric ions in his reaction mixture periodically increased and decreased.” In the reaction, there were yellow-coloured ceric ions that could be converted to colourless cerous ions. The overall colour of the reaction mixture oscillated with time, as the concentration of ceric ions increased and decreased periodically.

The chemistry community was highly sceptical of Belousov’s discovery, considering his results to be impossible. This was because of a mistaken belief that chemical oscillation violates the second law of thermodynamics, which dictates that the entropy of the universe must always increase. However, Belousov passed his experimental notes to another Russian chemist, Simon Shnoll, who set his young PhD student, Anatol Zhabotinsky, to work on the problem.

Zhabotinsky was fascinated. Not only was he able to reproduce Belousov’s work, but he brought the idea of oscillatory reactions to the attention of the chemistry community in a more convincing fashion. Now, nearly 70 years later, Irv and his team are building on these findings and are investigating ways to deliberately design chemical oscillators that have certain properties.

CHEMICAL OSCILLATORS

The reaction discovered by Belousov and developed by Zhabotinsky is known as the Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction. Oscillatory reactions have many exciting potential applications, from drug delivery to the analysis of chemical processes. Interestingly, they may even explain some of the earliest reactions that took place on Earth to produce life.

For chemical reactions where concentrations are constantly changing, the trick is to find patterns, like periodic oscillation, in the behaviour of the reaction. Similar periodic and patterned processes can be found in embryos that grow into organisms, or stalactites and stalagmites that develop in caves.

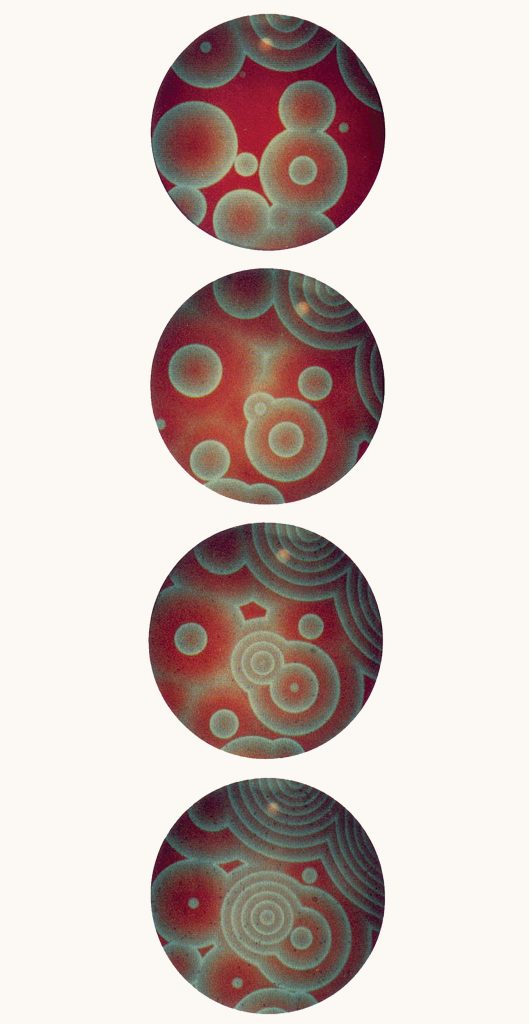

Irv and the Nonlinear Dynamics Group have made several new chemical oscillators and shown that coupled oscillators can be chimeric in their behaviour. In a coupled system, all the oscillators interact, but in some systems, not all of them show the same behaviour. In chimeric systems, some oscillators behave periodically, whereas others deviate from this and behave chaotically. It may seem like a giant leap in our understanding of the world around us, but Irv believes that oscillatory reactions can provide insight into natural, evolutionary phenomena.

“For instance, we may be able to explain why some organisms, like dolphins, can have half their brain in a sleep state while the other half remains alert to guard against predators.” In an example of some eye-catching chemistry, Irv has used colourless gels as a medium for the Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction to make a chemical reaction ‘dance’ when you shine light on it. During the reaction, the catalyst gains or loses electrons, triggering a polymer to change size and move, producing coloured waves in the gel.

Nonlinear chemical dynamics is a complex field, but chemists like Irv are uncovering the equations and physics to help us understand and model such reactions. Without this understanding, we would be unable to design chemical systems that behave as oscillators and have properties with useful applications. One example could be to use this fundamental knowledge to make systems that move toward or away from a source of light. All of this work gives us new insights into the rich and varied behaviour of chemical systems.

PROFESSOR IRVING EPSTEIN

PROFESSOR IRVING EPSTEIN

Henry F. Fischbach Professor of Chemistry

Brandeis University, USA

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Chemistry

FUNDERS: National Science Foundation, W.M. Keck Foundation, Army Research Office, DARPA, Howard Hughes Medical Institute (for science education efforts)

ABOUT CHEMISTRY

Chemistry is about understanding how atoms and molecules interact and react. This knowledge can be used for a wealth of applications, from designing and making new molecules to learning more about fundamental science. By studying new reactions and discovering new molecules, chemists might be able to find molecules with anti-cancer properties, for example, or for use in television displays. “These are exciting times for chemistry,” says Irv. “Many of the world’s most pressing issues – health, energy, climate change, water and food production – require a deep understanding of chemistry.”

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM147

LINEAR PROCESS – a process in which the observed value is linearly proportional to the input variable

NONLINEAR PROCESS – a process in which the observed value is not linearly scaled to the input variable

VARIABLE – a quantity that can take on different values at different times or positions

OBSERVABLE – what you measure or see in a process

OSCILLATION – a periodic change, like the tides in the sea or the motion of a pendulum

CHAOS – non-periodic, deterministic change, like the weather

Sometimes life is simple. You push an object, it moves. You push the same object twice as hard; it moves twice as fast. If you were to record the forces and speeds in an experiment, you would expect to see that the greater the force on the object, the faster it moves. If the speed of the object always increases in direct proportion to the force on it, this is known as a linear relationship. However, as Professor Irving Epstein and his team at Brandeis University in the US have shown, not everything is that simple – particularly in chemistry. Irv heads the Nonlinear Chemical Dynamics Group which investigates systems that show much more complex, nonlinear behaviour.

So, what does it mean when a process is nonlinear? In a linear process, the outcome is linearly proportional to the input variable. Let’s take the earlier example: If you pushed a box with twice as much force and the speed doubled, and then with four times as much force, and the speed quadrupled, this would be an example of a linear process. If you think of this process in terms of a graph, plotting a graph of input force against output speed would produce a straight line. But if, when you doubled the amount of force used, the speed increased by four times the amount, this would be an example of a nonlinear process. The ratio of speed to force is not constant, producing a nonlinear relationship, and plotting a graph of output speed against input force would produce a curve.

Nonlinear systems can be challenging to understand and sometimes show some unusual phenomena, including oscillatory behaviour of the observable process. Irv explains, “Common examples of nonlinearity beyond chemistry are population oscillations in a predator-prey system, like foxes and rabbits; the apparently (but not truly) random times at which a drop of water falls from a dripping faucet; the growth of the striped pattern on a tiger’s coat; the fractal structure of a snowflake.” While these phenomena are familiar to us, the nonlinear processes responsible for them are in fact difficult to predict and understand.

HOW DOES NONLINEARITY RELATE TO CHEMISTRY?

Oscillatory reactions are an example of nonlinear processes that occur in chemistry. These were originally discovered by accident by a Russian scientist called Boris Belousov in the 1950s. “Belousov was actually looking for something else,” says Irv. “While conducting his experiment, he happened to notice that the concentration of yellow ceric ions in his reaction mixture periodically increased and decreased.” In the reaction, there were yellow-coloured ceric ions that could be converted to colourless cerous ions. The overall colour of the reaction mixture oscillated with time, as the concentration of ceric ions increased and decreased periodically.

The chemistry community was highly sceptical of Belousov’s discovery, considering his results to be impossible. This was because of a mistaken belief that chemical oscillation violates the second law of thermodynamics, which dictates that the entropy of the universe must always increase. However, Belousov passed his experimental notes to another Russian chemist, Simon Shnoll, who set his young PhD student, Anatol Zhabotinsky, to work on the problem.

Zhabotinsky was fascinated. Not only was he able to reproduce Belousov’s work, but he brought the idea of oscillatory reactions to the attention of the chemistry community in a more convincing fashion. Now, nearly 70 years later, Irv and his team are building on these findings and are investigating ways to deliberately design chemical oscillators that have certain properties.

CHEMICAL OSCILLATORS

The reaction discovered by Belousov and developed by Zhabotinsky is known as the Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction. Oscillatory reactions have many exciting potential applications, from drug delivery to the analysis of chemical processes. Interestingly, they may even explain some of the earliest reactions that took place on Earth to produce life.

For chemical reactions where concentrations are constantly changing, the trick is to find patterns, like periodic oscillation, in the behaviour of the reaction. Similar periodic and patterned processes can be found in embryos that grow into organisms, or stalactites and stalagmites that develop in caves.

Irv and the Nonlinear Dynamics Group have made several new chemical oscillators and shown that coupled oscillators can be chimeric in their behaviour. In a coupled system, all the oscillators interact, but in some systems, not all of them show the same behaviour. In chimeric systems, some oscillators behave periodically, whereas others deviate from this and behave chaotically. It may seem like a giant leap in our understanding of the world around us, but Irv believes that oscillatory reactions can provide insight into natural, evolutionary phenomena.

“For instance, we may be able to explain why some organisms, like dolphins, can have half their brain in a sleep state while the other half remains alert to guard against predators.” In an example of some eye-catching chemistry, Irv has used colourless gels as a medium for the Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction to make a chemical reaction ‘dance’ when you shine light on it. During the reaction, the catalyst gains or loses electrons, triggering a polymer to change size and move, producing coloured waves in the gel.

Nonlinear chemical dynamics is a complex field, but chemists like Irv are uncovering the equations and physics to help us understand and model such reactions. Without this understanding, we would be unable to design chemical systems that behave as oscillators and have properties with useful applications. One example could be to use this fundamental knowledge to make systems that move toward or away from a source of light. All of this work gives us new insights into the rich and varied behaviour of chemical systems.

PROFESSOR IRVING EPSTEIN

PROFESSOR IRVING EPSTEIN

Henry F. Fischbach Professor of Chemistry

Brandeis University, USA

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Chemistry

FUNDERS: National Science Foundation, W.M. Keck Foundation, Army Research Office, DARPA, Howard Hughes Medical Institute (for science education efforts)

Chemistry is about understanding how atoms and molecules interact and react. This knowledge can be used for a wealth of applications, from designing and making new molecules to learning more about fundamental science. By studying new reactions and discovering new molecules, chemists might be able to find molecules with anti-cancer properties, for example, or for use in television displays. “These are exciting times for chemistry,” says Irv. “Many of the world’s most pressing issues – health, energy, climate change, water and food production – require a deep understanding of chemistry.”

Of course, investigations like those undertaken in Irv’s Nonlinear Chemical Dynamics Group take time, and many reactions will fail, but chemistry is a varied field and the possibilities are endless! Not all chemists wear white coats and mix chemicals in flasks. A whole range of research projects are carried out by Irv’s team. Of course, many of these research projects do involve conducting experiments, but some are purely theoretical and computational, “like developing and simulating a model for the behaviour of a set of coupled chemical oscillators,” explains Irv.

“Serendipity has played a significant role in this field,” says Irv. “Important phenomena are often discovered while looking for something else.” Belousov’s discovery of oscillatory reactions is a prime example of this and highlights why keeping an open mind is so important for any scientist.

ABOUT CHEMISTRY

According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational Outlook Handbook for 2019, “Overall employment of chemists and materials scientists is projected to grow 5 per cent from 2019 to 2029, faster than the average for all occupations. Chemists and materials scientists who have an advanced degree, particularly a PhD, are expected to have the best opportunities.” So, there are many excellent career opportunities in this field.

Most chemists will work in laboratories or in research teams, where teamwork and collaboration are key skills. “A modern research group is a diverse, multigenerational community of people from all over the world,” says Irv. “At any given time, our group might comprise undergraduates, graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, visiting professors, and even the occasional high school student.”

“I would recommend chemistry as a career to anyone who is fascinated by trying to understand the ways in which atoms and molecules, objects far too small for us to see, interact to produce the macroscopic world in which we live,” Irv continues. “If you enjoy solving these sorts of puzzles and would like to get paid to do this, you should certainly consider a career in chemistry.”

EXPLORE A CAREER IN CHEMISTRY

The American Chemical Society has lots of useful information on careers in chemistry as well as educational resources: https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/careers.html

Similarly, the Royal Society of Chemistry has resources to help you with your studies and read about future job options for chemists: https://edu.rsc.org/student

Irv’s Nonlinear Chemical Dynamics Group welcomes graduate students and undergraduates (and an occasional high school student) to the lab. Contact research groups near you and ask them whether they will provide a tour or come into your school/college.

Search the internet for ‘chemistry apprenticeships’ and there could be opportunities that suit you. For example, EDF Energy (https://careers.edfenergy.com/content/Chemistry-Apprenticeship/?locale=en_GB) and Nordmann (https://www.nordmann.global/en/career-withnordmann/training-programs-apprenticeshipstudies) offer chemistry apprenticeships.

According to the US Bureau of Labour Statistics, the average salary for a chemist is $77,600.

Irv recommends taking classes in maths, physics and biology at school, as well as studying chemistry. Most universities will offer degrees in chemistry and, to become a research chemist, a degree will be followed by a Master’s degree and/or PhD. As researchers, chemists often specialise in sub-disciplines of chemistry, such as physical, organic or inorganic chemistry, or focus on even more specific topics.

HOW DID IRV BECOME A CHEMIST?

DID YOU KNOW YOU WANTED TO BE A CHEMIST WHEN YOU WERE YOUNGER?

I always knew I was interested in maths and science. I didn’t decide on chemistry until my first year at university.

WHO OR WHAT INSPIRED YOU TO GET INTO CHEMISTRY?

My high school had a very good chemistry programme and an outstanding chemistry teacher, Miss Butler. Then, my first college chemistry course was taught by William Lipscomb, who later won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. I think I also just liked mixing things together and seeing colours change or flames appear!

IS THERE A CHEMIST WHO YOU PARTICULARLY ADMIRE?

William Lipscomb was not only a brilliant chemist, but a wonderful person, who provided wise counsel and unflagging support for his students. He received the Nobel Prize for his work on inorganic boron chemistry, then turned to unravelling the structures of biologically important proteins, where again he made major contributions. As well as being a chemist, he was also a concert-level clarinetist and an avid tennis player!

ARE THERE ANY EXPERIMENTS YOU WISH YOU COULD DO BUT CAN’T FOR ONE REASON OR ANOTHER?

The oscillating reactions we study tend to have periods of a few seconds to a few hours. I wish we had the tools to find and manipulate oscillations at much shorter time scales. Similarly, it would be nice to be able to study pattern formation at the nanoscale.

YOUR GROUP HAS PUBLISHED HUNDREDS OF PAPERS OVER PAST DECADES. OF ALL THESE ACHIEVEMENTS, IN WHICH DO YOU TAKE THE GREATEST PRIDE?

The discovery of the first deliberately designed oscillating reaction remains the high point for me. This is in part because our proposal to undertake the project was turned down three times by a sceptical National Science Foundation before they agreed to fund it, and then, once we began it, our idea worked within a month.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW NOW THAT YOU WISH YOU’D KNOWN WHEN YOU WERE YOUNGER?

There are two things. The first is that persistence, resilience and hard work (as well as a good dose of luck) count for at least as much as natural intelligence. The second is that starting off in one career direction does not determine one’s destiny. Change is always possible, and often desirable.

IRV’S TOP TIPS

01 Try to figure out what you enjoy doing and what you’re good at. Then, look for a career that puts you within the intersection of these domains.

02 “Chance favours the prepared mind” is not just a motto for nonlinear chemical dynamics, but also for thinking about future careers. It never hurts to think about your career options and plan in advance.

Do you have a question for Irv?

Write it in the comments box below and Irv will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)