Why electoral systems matter for democracy

There is huge variety in the methods that democracies around the world use to elect legislators and leaders. Professor André Blais, from the University of Montreal in Canada, and Professor Damien Bol, from King’s College London in the UK, believe that this variety can lead to very different outcomes – in terms of who gets elected and which policies get implemented.

Talk like a political scientist

Civic duty — the responsibilities people have in a democracy

Electoral system — the rules on how people vote and how votes are counted to determine who is elected

First past the post (FPTP) — an electoral system where a candidate or party wins through achieving the highest number of votes/a relative majority

Government — the body that makes and enforces laws

Legislature — the body that votes laws into effect

Polarisation — when people are divided into groups that are strongly opposed to each other

Political party — an organisation whose members have similar political views and which puts forward candidates to stand in elections

Proportional representation (PR) — an electoral system where parties gain seats in proportion to the number of votes they receive

Seat — an elected position on a government body, representing, for example, a constituency or electoral area

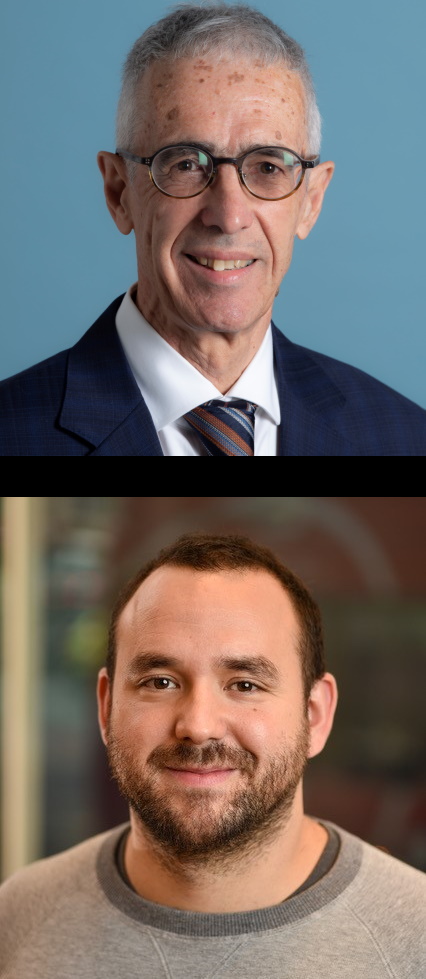

For centuries, politicians and philosophers have debated what the ‘ideal’ democratic system is –which system best represents voters’ interests. A lot of unknowns still remain around this question, which is made especially challenging to answer given the many other political, cultural and systematic variations between nations. Professor André Blais, from the University of Montreal, and Professor Damien Bol, from King’s College London, are political scientists who have joined forces to examine how different electoral systems affect voter and party behaviour.

Variety in electoral systems

We might assume that democracies have similar electoral systems, but, in fact, there is huge variation across countries. “I think people often underestimate the variety of electoral systems that exist around the world,” says Damien. “Most people understand the electoral system of their own country and, perhaps, a few others like the US or the UK, but there are so many more than that.”

This raises the question of how a country decides on which electoral system it adopts. “Politicians prefer systems that they think will offer them an advantage, and there are also historical and cultural factors at play,” explains André. “However, we have only a limited understanding of how these factors lead to such variation between nations.”

This introduces a key challenge for the study of electoral systems. “Finding a way to isolate the effect of the electoral system from other political factors is not easy,” says Damien. “Countries tend to be different in so many ways – so we have to get creative.” This is why André and Damien run experiments with simulated elections in the lab, to see how electoral systems influence participants’ behaviour. “The first experiment I did with André was in a lab in Montreal, where we put volunteers into two groups and got them to participate in elections under various electoral systems,” says Damien. “It was fascinating to see research happening right in front of our eyes like that.”

Types of voting systems

While electoral systems vary hugely, many can be grouped into two broad categories: proportional representation (PR) and first past the post (FPTP).

In a PR system, the number of seats a party wins is in proportion to the share of the votes it receives. For example, if one party wins 42% of the votes, it will receive 42% of the seats. This system is used by the majority of European countries and many other nations around the world. “The advantage of the PR system is that it improves the representations of minority viewpoints in the legislature,” says André. “PR does result in a more representative government, but this might not translate to policy change.” This is because governments run by several parties will find it more difficult to agree on policies. “Differences in party perspectives and promises make it harder to react to shifts in public opinion and adjust the policies accordingly,” explains Damien.

FPTP systems, on the other hand, see whichever candidate receives the most votes for a specific seat winning that seat. The party that wins the overall election is the party that wins the most seats. The votes for candidates that lose any specific seat have no direct bearing on the results. This tends to produce single parties holding a majority in government. This system is used in the US, Canada and the UK. FPTP systems can be criticised because they are typically less representative of the population’s views; larger parties tend to the number of win proportionally more seats compared to the number of votes they receive, while smaller parties tend to win proportionally fewer seats, if any. However, there are also advantages. “There is evidence that governments are more likely to fulfil their electoral promises under majority systems such as FPTP,” says André. “It’s easier for parties to fulfil their promises when they govern alone,” adds Damien.

Influencing voter turnout

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM434

“Making voting compulsory increases turnout by 10-15 percentage points,” says André.

© Suzanne Tucker / Shutterstock.com

We might assume that democracies have similar electoral systems, but, in fact, there is huge variation across countries.

working well around the world,” says Damien. © Yeexin Richelle / Shutterstock.com

Politicians often debate how to get more voters to turn up at the polls, but André believes voter turnout comes down to one simple variable. “Making voting compulsory increases turnout by 10-15 percentage points,” he says. “This is, in part, because people want to avoid penalties, but also because compulsory voting makes people think about civic duty more.”

Damien points to further influencing factors. “Many people think that PR systems have higher turnout compared to FPTP systems, but we don’t have clear evidence of this,” he says. “What seems to matter more is the number of parties involved, which tends to be higher under PR than FPTP; turnout is higher when there are more parties to vote for. We can increase the number of parties in many ways, such as by lowering the bureaucratic requirements to compete in elections.”

Measuring democracy’s success

Though the study of democracy is complex and multi-faceted, there is a fairly clear way to assess whether an electoral democracy is functioning well. “When parties peacefully accept the outcome of an election when they are on the losing side, electoral democracy works,” says André. “Democracy still works well in most established democracies – though the fact that a substantial fraction of Republicans believe that Trump won the US’s 2020 election is concerning.”

Other factors also contribute to a democracy’s success. “By and large, electoral democracies are working well around the world,” says Damien. “Studies show that successful parties tend to fulfil most of their electoral pledges, and the policies adopted tend to follow the views of the population. To me, a key challenge right now is to preserve people’s faith in elections and representative democracy.” A loss of faith in the democratic process can destabilise democracy. “Although a majority of people support democracy, they might lose trust in politicians, especially those not from their preferred party,” says Damien. “This might lead them to contest electoral results.”

Political science still has many unanswered questions, and André and Damien aim to keep delving deeper into electoral systems. “I am particularly interested in systems that allow voters to support more than one party or candidate, and whether this helps decrease polarisation,” says André. Damien aims to look further into how different electoral systems affect losers’ consent. “I’d like to find ways to ensure that everybody, including the losers, keeps faith in the electoral process,” he says.

Professor André Blais

Professor André Blais

Department of Political Science, University of Montreal, Canada

Professor Damien Bol

Department of Political Economy, King’s College London, UK

Field of research: Political science

Research project: Using observational and experimental approaches to analyse how different electoral systems affect voter behaviour and electoral outcomes

About political science

The field of political science involves studying systems of government, elections and other forms of political participation, public policies and international relations. It is a highly important field, given that elected (and non-elected) representatives and their governments make the decisions that shape our world for better or worse.

Approaches to political science

André often takes an observational approach to the study of political systems. “I am always curious to see the different rules that exist around the world,” he says. “For instance, the outcomes of elections in smaller countries that I am unfamiliar with can often yield important lessons.” Damien takes an analytical approach. “I see electoral systems and countries as data points that I use to test hypotheses,” he explains. “My ultimate goal is to find ways to make the world a better place.”

Variability between nations makes the study of electoral systems complex. “Correctly identifying the consequences of various electoral systems is the main challenge for me,” says André. “I like to compare patterns before and after a given system has been modified.” Damien adds that a combination of approaches can be especially fruitful. “If we use a variety of approaches and see they all point in the same direction, we can be confident that we’re on to something important,” he says.

Collaboration

“Unlike in natural sciences, teams of collaborators are usually smaller in political science,” says Damien. “It’s usually a handful of scholars who work on similar topics that decide to work together on a specific study.” However, times are changing, and larger teams with set responsibilities are increasingly becoming the norm. “I see more large teams with a clear division of labour,” says Damien. “Students are increasingly involved in these large teams, which is a great opportunity for them to acquire some hands-on experience.” Damien says that working in teams is more fun and more motivating, and André agrees. “Working with great researchers, listening and learning from them and, sometimes, convincing them about a method, is pure delight,” he says.

Additionally, the rise of the computer age has created big opportunities for political science. “Huge data banks are being created, which opens up all sorts of doors,” says André. However, it can be difficult to know where to begin when faced with such vast volumes of data. “Being part of a large team, and having a specific role within that team, can really help a researcher, especially a student, to know how to handle data,” says Damien. “I hope that universities will adjust their financial systems to this new reality, so professors have the resources to work directly with students and introduce them to this world.”

Pathway from school to political science

• As well as political science, if it is available, Damien and André recommend taking economics, maths and psychology at school and post-16.

• Suitable undergraduate degrees can include political science, economics, public policy, psychology and sociology.

Explore careers in political science

• André recommends looking at PS: Political Science & Politics, a journal with many open-access articles that give an overview of the discipline.

• Damien recommends finding political scientists who have done research that interests you. Reading their LinkedIn profile page or visiting their personal website could provide useful tips, links and further information about their work.

• According to Glassdoor, the average salary for a political scientist is around CAN $85,000 in Canada, and around £38,000 in the UK.

Meet Damien

I got really into politics as a teenager. I think my interest came from my dad and grandad who used to discuss politics around the dinner table. My high school history teacher was also passionate about the politics behind big historical developments like the American and Russian revolutions, which really fascinated me. That’s why I decided to take a political science major at university.

Growing up in a relatively small country like Belgium, our media focused a lot on global politics. I consider this an advantage, compared to larger countries whose media tend to focus on their own politics. I was exposed to different political and electoral systems very early on, which triggered my interest in how differences between systems can shape nations.

I’m convinced of the power of democracy and try to defend it in my research. I aim to find ways to improve the democratic process, as keeping people engaged is essential for stability. I also like the process of research – from having an idea to data collection, to analysis and writing up the results. I love the feeling of finishing an academic paper that will, hopefully, advance our collective knowledge.

Attention to detail, self-discipline and creativity are all attributes that have helped me become a successful researcher. I’m also a ‘people person’ – I get along with people and love interacting with colleagues and listening to their ideas, goals and problems. Academia is full of people who are so much in their own head that they can seem cold to others; I believe my sociability has helped me reach leadership positions quite early in my career.

I was once told that I should be more selfish in the use of my time and energy. This doesn’t work for me at all. I thrive through interactions with others and become miserable when I’m only working on my own projects.

I was the Director of the Quantitative Political Economy Group at King’s College London for five years. I was able to really participate in shaping the group, through launching activities such as an annual workshop for PhD students in London that has the reputation of being one of the friendliest and most ‘chilled’ events in the field. Helping the group grow and increase its visibility and reputation was a huge achievement for me, and the gratitude of my colleagues meant the world.

I’m very excited to be moving to the Paris Institute of Political Sciences, known as Sciences Po. I hope to contribute to this terrific institution like I did at King’s. As a native French speaker, I feel I’m also coming back to my ‘roots’, though I also hope to take over some things I learnt in the UK, such as a slightly different teaching style, which could bring another perspective to students there.

Damien’s top tip

Pay attention to people around you. Everybody has something interesting to say; this is the best way to learn.

Meet André

I grew up in a time of great optimism for solving collective problems. Political science seemed to be a great choice to take part in this ‘quiet revolution’. I studied elections because of my great interest in ordinary citizens, and elections are the simplest way for citizens to engage in politics. I also like maths and quantitative analyses, and political science provides great data to use these skills.

I have a huge curiosity about how people behave. I want to understand how and why people do what they do in elections. I also have a deep scepticism for conventional wisdom – my motto is ‘not convinced’! I find this helps a lot in challenging assumptions about the world.

I am proud to have supervised many great PhD students and postdocs. Seeing them go on to thrive in the field, while keeping in touch and even collaborating with them later on, is very rewarding.

André’s top tips

1. Follow your passion, breed healthy scepticism, and collaborate with others.

2. When faced with a difficult project, work on the most challenging task first – for a researcher, that’s usually writing!

Do you have a question for André or Damien?

Write it in the comments box below and André or Damien will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)