Can we predict where falling rocks will go?

Rockfalls can cause serious damage to people and infrastructure. To design useful protection measures, it is important to understand what happens during a rockfall and where any rocks might go. At Boise State University in the US, geotechnical engineer Professor Nick Hudyma and his team, including PhD student Grant Goertzen, are throwing rocks down slopes to initiate artificial rockfalls. These experiments will allow them to create computer simulations that model how real rockfalls might occur.

Talk like a geotechnical engineer

Coefficient of restitution — a measure of how elastic a collision is, showing how much energy a rock retains after hitting the ground

Freeze-thaw weathering — the mechanical process that breaks rocks when water seeps into cracks and then freezes and expands

Impact scar — a mark left on a slope after it has been hit by a rock

Lidar — a survey method that uses lasers to create high-resolution topographic maps

Rockfall — the movement of loose rocks down a slope

Rotational velocity — the speed at which an object rotates around an axis

Simulation — a digital recreation of a real-world event based on mathematical models that represent the behaviour of the system

Trajectory — the path a rock follows as it moves down a slope

If you have ever driven along a mountain road, you may have seen signs warning of falling rocks. These warnings exist for good reason. Rockfalls happen when pieces of rock break away from steep slopes or cliffs and travel downwards, often at high speeds. Rain, freeze-thaw weathering, earthquakes and even human activities like construction or rock climbing can set them in motion.

Why is it important to study rockfalls?

“Rockfalls pose a substantial danger to people and infrastructure, especially in mountainous and coastal regions,” says Professor Nick Hudyma, a geotechnical engineer at Boise State University. Anchoring loose rocks can prevent rockfalls, but it is often expensive and impractical. Another option is to let rocks fall naturally while limiting their damage by installing protections such as nets, ditches and barriers. “To place these protections wisely, we need to know where any falling rocks may travel,” explains Nick.

To determine this, Nick and his team create artificial rockfalls which allow them to develop computer simulations that can be used to model how real rockfalls may occur. “Our artificially induced rockfalls help us better understand rock movement, enabling us to protect people and infrastructure,” he says.

How did the team create artificial rockfalls?

In reality, an artificial rockfall simply involves throwing a rock down a slope! But there was a lot more scientific work that went into the team’s experiments, which were carried out in gravel pits. A single day in the field takes weeks of preparation. In addition to organising transport, equipment and safety gear, the team also conducted preliminary mapping and simulations. This involved flying drones equipped with lidar to create high-resolution topographic maps of each site and using these maps to model where the rocks were likely to go. This was critical so that the team knew where to place cameras and sensors to collect data during the rockfalls.

“On the day of testing, we arrived just before sunrise because there was a lot of preliminary set-up and testing to do before we could drop our first block,” says PhD student Grant Goertzen. The team used artificial concrete blocks rather than real rocks which gave them greater control and allowed them to study how rock shape affects rockfall behaviour. The blocks were painted bright pink and came as spheres, cubes, cylinders and rectangular prisms. Each weighed between 35 kg and 135 kg and had a tube leading to the centre where a sensor was placed to track the block’s motion. “These blocks were too heavy to just pick up and toss off the slope!” says Nick. “So, we also had to design and build a moveable hoist system to lift and safely release them.”

“It was so exciting to see the first block travel downslope!” says Grant. “After it came to rest, we were all cheering! Then, after those celebrations, the real work began.” The team spent the day releasing block after block down slopes of different length, gradient and material (sand, gravel and cobbles). For each rockfall, the team measured the block’s progress down the slope using high-speed cameras, drones and the internal motion sensors. After recording where the blocks came to rest, they had to be transported back up to the top of the slope using the hoist system so they could be released again. Once all the tests were done, the slope was rescanned with lidar to capture the impact scars carved into the surface. “Finally, we had to pack everything up and head home,” says Grant. “It was a long and exhausting day, but also so much fun!”

What did the rockfall experiments reveal?

“There are many factors that influence the trajectory of a block, including its size and shape, and the stiffness and angle of the slope,” explains Nick. The team discovered that shape plays a huge role in how a block travels downslope and where it comes to rest. Spheres travelled the fastest and farthest, rolling smoothly over obstacles, while cubes and rectangular prisms were more affected by the terrain and travelled less far. As more blocks were released, impact scars formed on the slope and some rectangular prisms even became trapped in these grooves. One unexpected observation was the behaviour of the cubes – their sharp faces acted like lever arms and caused sudden changes in rotational velocity each time they hit the ground.

How will these artificial rockfalls help geotechnical engineers?

The team is now analysing the large dataset collected in the field, including lidar maps of slope surface features before and after the rockfalls, soil measurements, motion sensor readings, videos of each rockfall and the final resting place of each block. They will study the photos and video footage to understand how each block moved downslope and, by synchronising the videos and sensor data, they will calculate the coefficient of restitution – a key property that controls how a rock bounces each time it impacts the ground during a rockfall.

Using these insights, the team will run new computer simulations to try to digitally recreate the experiments. “Our hope is that we can successfully simulate our field tests to provide confidence in our future simulations,” says Nick. “Our work will better inform geotechnical engineers about the role of soil and slope properties in rockfalls and their influence on how rocks move downslope and where they will eventually come to rest. This information can be used to design better rockfall protection systems.”

Professor Nick Hudyma

Professor Nick Hudyma

Grant Goertzen

Department of Civil Engineering, Boise State University, USA

Fields of research: Civil engineering; geotechnical engineering

Research project: Creating artificial rockfalls to develop simulations of rockfall hazards

Funder: This material is based upon work supported by the US National Science Foundation (NSF) BRITE Program under Award No. 2349009. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF.

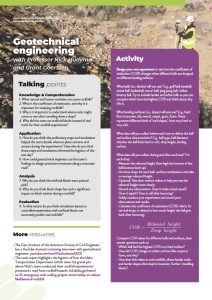

About geotechnical engineering

Geotechnical engineering is the branch of civil engineering that focuses on the ground beneath our feet. While civil engineers design, build and maintain infrastructure like bridges, roads, buildings and pipelines, geotechnical engineers ensure these structures are safe and stable by studying the properties of the soils and rocks they are built on or in. Every building, tunnel, bridge and road depends on solid understanding of the ground that supports it.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM663

“Geotechnical engineers determine the properties of soils and rocks for construction,” says Nick. “They also design foundations (for buildings and bridges), subsurface systems (such as pipelines and tunnels) and slopes (along highways and railroads). And they are responsible for assessing, predicting and repairing damage caused by geological hazards, such as earthquakes, landslides and rockfalls.”

Careers in geotechnical engineering are varied and exciting. Some engineers work in the lab or field, testing soils and rocks to understand their strength, while others analyse data and run computer simulations to model how the ground will behave during construction. “You should be excited to pursue a career in geotechnical engineering because it offers a variety of experiences,” says Grant. You will get to enjoy a mix of outdoor teamwork, technical problem-solving and collaboration with multidisciplinary teams. “Most importantly, you will be part of a profession that prioritises the well-being of society and the environment in your design, construction and maintenance decisions,” says Nick. “Geotechnical engineers are driven by a dedication to serving the public and improving communities.”

Pathway from school to geotechnical engineering

At high school, study science and mathematics. “It is important that aspiring geotechnical engineers have a good understanding of math, statistics, physics and chemistry, as these are the background of all engineering,” says Nick.

At university, study an undergraduate degree in civil engineering and take courses in geotechnical or geological engineering. These will cover topics such as soil and rock mechanics, slope stability, and computer simulations. You can then study a postgraduate degree in geotechnical engineering.

“All engineers are problem solvers, but geotechnical engineers are also naturally curious about the world around them,” says Grant. “Most of us have an interest in geology or Earth sciences, and we use those interests to help us solve practical infrastructure problems.”

Explore careers in geotechnical engineering

“If you like solving problems, are interested in geology or the natural world, and would like to design and construct infrastructure, then geotechnical engineering may be for you!” says Grant.

Careers in geotechnical engineering range from designing foundations for buildings to studying natural hazards.

Explore organisations such as the Geo-Institute of the American Society of Civil Engineers (geoinstitute.org), the International Society for Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering (issmge.org) and the British Geotechnical Association (britishgeotech.org) to find information about research and careers in the field.

Prospects provides information about what a career in geotechnical engineering could involve, the qualifications you will need and the salary you can expect (prospects.ac.uk/job-profiles/geotechnical-engineer)

“At Bosie State University, we host outreach events to inform students about civil engineering and the cool things we do,” says Nick. “If you are ever in Boise, I would love to show you our laboratory facilities and talk about the exciting projects our students are working on!”

Meet Nick

I was fortunate to grow up in an area surrounded by nature, and I was always curious about how the landscapes I could see came into being. When I was young, I was fascinated by earth-moving equipment. As a teenager, I enjoyed playing sports, writing computer programs and riding my bike around town.

There are no engineers in my family. But I was good at math and science so, when I went to university, I decided to study engineering. I was fortunate to have the opportunity to study geological engineering, which focused heavily on understanding the properties of natural materials. It was a wonderful combination of my interests in engineering and geology.

When I became a professor, I wanted to study geological hazards so I could continue to combine my interests in engineering and geology. In Florida, I focused on sinkholes. When I moved to Boise in Idaho, I was excited to study rock-related hazards such as rockfalls.

I am so happy that, as a geotechnical engineer, I get to work outside as part of my job. My favourite experiences are working with students who share my passion and want to understand how natural materials behave. Fieldwork is very important in geotechnical engineering, but not everyone enjoys that sort of work. During our recent fieldwork, I was so impressed by how well the rockfall team performed and worked together to accomplish our goals. Seeing the first drop test is something I will never forget.

In my free time, I like to play ice hockey and hang out with my dog, Asta. But my favourite thing is long weekend bike rides along the Boise Greenbelt where I can be alone and think about the next cool project.

Nick’s top tip

Try different things to find your passion. Who knows? That passion may become a cool hobby or even your career. If you are really interested in something, it is easy to work hard and be dedicated to it.

Meet Grant

As a teenager, I loved being outside and being active. I had a lot of hobbies like fishing, hiking and cliff jumping, but my primary interest was rock climbing.

I come from a family of civil engineers, so I grew up loving math and construction. My dad and both my grandpas were civil engineers – one of whom is still practising at nearly 80 years old! During junior year of my civil engineering undergraduate degree, it was Dr Hudyma and the other geotechnical professors at Boise State University who motivated me to choose geotechnical engineering as my area of interest.

The best part of studying rockfalls is the surprises! Research is all about exploring and understanding new concepts, so when experiments lead to unexpected outcomes, it’s exciting. The real challenge (and reward) comes from figuring out why those surprises happened.

Fieldwork can be hard work – it turns out, lifting the 15,000th pound of rock in a day is not as easy as the first pound! By the end of the day, we were exhausted! Before a field day, we do lots of planning to determine all the testing procedures. During our fieldwork, we made a change to one of our procedures, but we didn’t adequately assess the impact of this change. This resulted in one of our sensors recording no data for the day! Thankfully the test site is only 15 minutes away from campus so we can easily go back and collect additional data from the site.

In my free time, I love being active outdoors. I love rock climbing, both indoors and outdoors, which fits perfectly given my research! I also enjoy running, hiking, mountaineering, cliff jumping, fishing, and playing sports like basketball, football and volleyball.

Grant’s top tip

Work hard at whatever you are doing (but that doesn’t mean work all the time!). And put your best effort into the task at hand. Building good habits of focus and effort will carry you a long way.

Do you have a question for Nick or Grant?

Write it in the comments box below and they will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

While Nick and Grant throw rocks down slopes to protect people from rockfall hazards, other civil engineers are blowing things up to protect people from explosions:

futurumcareers.com/out-with-a-bang-the-challenge-of-measuring-explosions

0 Comments