Engaging history: the educational impact of medieval objects

At the University of Chester in the UK, historians Professor Katherine Wilson and Dr Thomas Pickles are seeking to reinvigorate history education through the incorporation of everyday medieval objects. Their approach, emphasising hands-on exploration and critical inquiry, demonstrates how material culture profoundly enhances historical understanding and pedagogy.

Glossary

Historical inquiry — investigating and analysing historical sources, events and interpretations to gain knowledge about the past

Material culture — the physical objects that are created, used and valued by people in a particular society

Medieval — the 5th to 15th centuries, often referred to as the Middle Ages

Mobility — the movement of objects across geographical, cultural and social boundaries

Pedagogy — the method and practice of teaching, focusing on strategies for effective learning

Source analysis — the critical examination of historical artefacts to understand the past

The educational value of museums and galleries stems from their collection, preservation, interpretation and exhibition of various objects. Whether a museum showcases valuable artworks or everyday items from different cultures and time periods, the principle remains the same. Objects provide tangible evidence of people, places and events, and each object has its own story to tell.

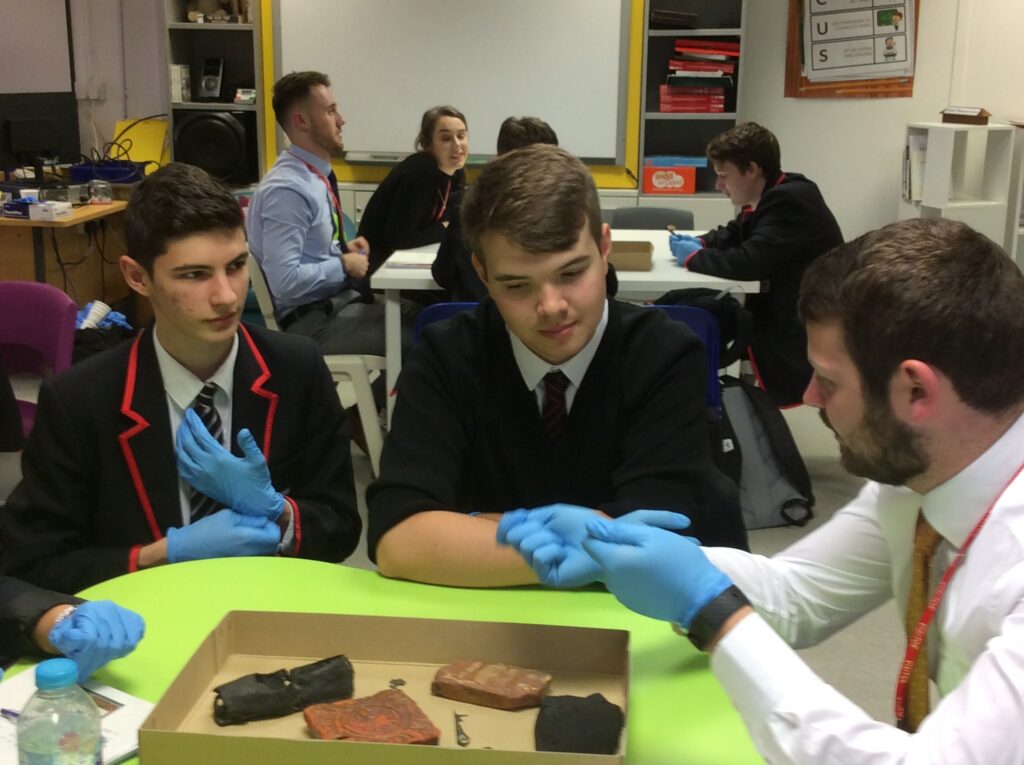

Give a student an object to examine and you will almost always capture their interest – a crucial first step in the learning process. Unlocking the educational potential of objects depends on how we observe, analyse and discuss those objects. It requires asking the right questions – ones which stimulate conversations and prompt reflection. Consider some everyday objects from the past such as keys, floor tiles or shoes. How can these seemingly prosaic objects contribute to historical inquiry? What clues do they hold about belief systems or social structures? Most importantly, how can they impact how history is taught in our classrooms?

Professor Katherine Wilson and Dr Thomas Pickles, historians at the University of Chester, aim to transform how students engage with the past by integrating everyday medieval objects into history education. Through hands-on exploration and critical inquiry, these objects demonstrate the significant impact that material culture can have on historical understanding and pedagogy.

Motivation

“Our project, which was generously funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, was principally motivated by a need to increase access for students and educators to museum collections,” says Katherine. “In recent years, exacerbated by the pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis, there has been growing concern over student access to museum collections and the consequences non-access has for widening participation, cultural enrichment and creative education.” In 2022, VoteforSchools conducted a study involving 32,000 primary and secondary students aged 5-16. One primary school student from Berkshire emphasised the significance of museum access, stating, “School trips are really fun, and they help us learn about the world. Not all families can take their children to new places, so it’s important that schools can give children this experience.”

It is also essential to recognise that history is often regarded as a challenging subject, perceived to involve passive learning and rote memorisation of facts. It is this common perception among students that led to the development of ‘The Mobility of Objects Across Boundaries 1000- 1700 (MOB)’ project, aiming to inspire teachers to use more material objects in history classrooms. “We wanted to make clear the value of handling material objects for the subject of history in terms of source analysis, developing historical connections and in making historical inferences,” explains Thomas. “Asking students to closely investigate original historical objects from basic questions and then to produce work on an object, regarding its makers and mobility, establishes the fundamental tools of the history discipline in students.”

Handling authentic artefacts

Engagement with authentic artefacts is an important learning tool which promotes inclusivity and absorption. Through hands-on interaction, students are encouraged to actively participate in discussions and knowledge application. “For us, there was real significance in the way that the handling of the authentic objects was intertwined with a dialogue process,” explains Katherine. “It allowed students to ask questions, problem solve, investigate, apply knowledge and make new meanings all constructed in a social group situation.” Once students begin interacting with these medieval objects, it often leads to an open atmosphere of engaged and spontaneous conversation, facilitating deeper understanding and appreciation of history.

Object selection and contextual understanding

To select objects for the project, Katherine and Thomas carefully curated a variety of everyday medieval items from the collections of the Grosvenor Museum in Chester. This included six types of objects: keys, chests, shoes, tiles, ceramics and pottery, coins, and pilgrim badges and devotional tokens. The aim was to use objects that not only represent daily life during the medieval period but also lack known historical narratives or identifiable owners, allowing students to explore their significance without preconceived notions.

“The handling and use of the objects revealed student’s contextual knowledge of status, power relations and mobility during the medieval period, especially in terms of inequalities in power, exploitation of individuals and movement of peoples for trade and spiritual journeys,” says Thomas. “Students were supported to understand this context through ‘first principle’ questions when handling the objects (e.g., What pictures can you see? What do you think it was made of? Who do you think it belonged to?), and through a variety of teaching resources to extend their learning, including digital reconstructions, timelines, and short films on the objects.”

By incorporating these multifaceted approaches, students were empowered to construct richer understandings of the past, bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical engagement.

Facilitating meaningful discussions

These objects spark dynamic discussions between teachers and students, cultivating a collaborative approach to historical inquiry. By handling the objects, discussing them and producing work based on them, students actively contribute to the construction of historical knowledge alongside their teachers. “These discussions between student and teacher are important as it enthuses both parties about the study of history, turning the subject away from any perception of being a subject of knowledge transfer and learning of facts,” explains Thomas.

Project highlights

One of the highlights for Katherine and Thomas has been the collaborative effort with established and trainee history teachers and students to co-create their project. “Because the students’ work often focused on narratives of nonelite peoples and places in the past, this accurately reflected the explosion in the production and ownership of objects by a far wider range of people,” says Katherine. “In these ways, the students’ work on the objects was impressive and authentic, and their observations, along with our examination of the objects as historians, have offered intriguing starting points to our ongoing research into the mobility and transformations in material culture in the medieval period.”

Impact on students

The integration of authentic medieval objects into history education has sparked profound reactions among students, revealing layers of curiosity and imagination that extend beyond the boundaries of traditional learning. As students encountered these objects, their fascination led them to sacrifice their breaks and lunchtimes to further explore the historical narratives embedded within them. “Their imaginations evocatively set the objects into very human contexts, full of meaning, when asked to write about their makers, production processes and movements,” says Katherine. “In the work undertaken by the students, they wrote about tilers wanting to spread enlightenment and revelation through the beauty of their decorated tiles; keys inadvertently being fumbled onto the floor to lie for centuries undiscovered between cracks in tiles; pilgrimage badges representing long and arduous journeys, for both showing off and anxious safekeeping; shoes that were comfortable and fondly cherished, but that had been damaged through long wear for work.” The students’ responses went beyond mere descriptions; they were infused with critical historical inquiry and meaningful discussion, encouraging deeper comprehension and involvement. By exploring real artefacts from the past, students moved beyond the limitations of textbooks, breathing life into historical narratives often overlooked in traditional teaching methods.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM496

All photos: University of Chester Photography, Katherine Wilson and Mike Bird

Impact on teachers

The Mobility of Objects across Boundaries project prompted educators to fundamentally reconsider their approach to historical sources and teaching methods. Many teachers commented on how handling authentic objects provided a new lens through which to engage with historical material, allowing students to make historical inferences without extensive prior contextual knowledge. This reversal of the traditional teaching process highlighted the power of primary sources to spark inquiry and critical thinking in the classroom. Trainee teachers also benefitted significantly from their involvement in the project, gaining first-hand experience in implementing object-based learning across diverse classroom settings. “One of the trainee teachers noted that, ‘I was able to plan the same experience for students in both placement schools during my training. The artefacts were met with the same level of interest and respect, no matter the age, ability or gender of the students’,” says Thomas. Witnessing students of varying ages, abilities and backgrounds engage with artefacts with equal levels of interest and respect showed the universal appeal and significance of hands-on historical inquiry. This experience not only reaffirmed the importance of experiential learning but also deepened teachers’ appreciation for the care and respect students inherently possess for history when provided with meaningful opportunities for interaction.

Advice for teachers

Integrating objects into history education may seem daunting for educators accustomed to traditional teaching methods. However, embracing this approach can have profound benefits for both teachers and students alike. “Working with objects in the classroom can change student perspectives on the study of history, give them enhanced historical skills and allow them to become co-creative learners along with you as a teacher,” says Katherine.

If you are unsure where to begin, consider starting with everyday objects that offer rich historical insights. “We would recommend approaching your local museums or collections to see which artefacts they might be able to loan to you for handling sessions with students,” advises Katherine. “We found non-elite, everyday objects without known historical narratives or owners were the most engaging and useful for students to handle and question.”

Accessing artefacts for classroom use has become increasingly accessible thanks to online platforms and museum initiatives. Many museum collections offer loan boxes of artefacts that educators can apply to access. “Our Mobility of Objects website also has lots of useful, free downloadable resources you can use to help support your journey into handling objects in the classroom,” says Thomas. By taking these steps and embracing the potential of object-based learning, educators can enrich history education, empower students as active learners, and promote a deeper understanding and appreciation of the past.

Looking ahead, Katherine and Thomas plan to publish further papers on their work at an international level, advocating for the integration of object teaching into the subject of history. By sharing their findings and encouraging more teachers to use museum loan boxes, they aim to enhance historical education and promote a deeper engagement with the past among students worldwide.

Professor Katherine Wilson

Professor Katherine Wilson

Associate Professor of Later Medieval European History, University of Chester, UK

Dr Thomas Pickles

Associate Professor of Early Medieval History, University of Chester, UK

Field of research: Later medieval European history

Research project: The Mobility of Objects Across Boundaries 1000-1700: inspiring teachers in using more material objects in history classrooms

Funder: UK Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC)

Meet Thomas

I am a historian of the Earlier Middle Ages (400-1200) interested in the relationship between social structures, individual agency and cultural change – particularly religious conversion and church building.

My monograph, Kingship, Society, and the Church in Anglo-Saxon Yorkshire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018) explored the social dynamics of religious conversion and church building in the kingdom of the Deirans (modern Yorkshire), from 400-1066. I am the Principal Investigator of an Arts and Humanities Research Council funded project called ‘Early Christian Churches and Landscapes’.

After completing my BA in History, Master of Studies in Historical Research, and Doctorate at Wadham College, University of Oxford, I worked as a Fellow by Special Election and Lecturer at St Catherine’s College, Oxford from 2005- 2009, a Lecturer at the University of York from 2009-2012, and a Lecturer at Birkbeck from 2012-2013, before arriving at Chester in 2013.

Meet Katherine

I am a historian of the European Later Middle Ages (1300-1500) interested in the shifting patterns and uses of material culture. I am the Principal Investigator of the AHRC funded ‘The Mobility of Objects’ project, partnered with the University of Oxford, the Grosvenor Museum, and Children and Education Services at the University of Chester.

This work has produced public exhibitions, public handling sessions, object boxes for loan to schools, digital reconstructions of medieval city sites and extensive teaching resources for Key Stages 1-3 and for all levels of the school curriculum.

My monograph, The Power of Textiles: Tapestries of the Burgundian Dominions (Turnhout: Brepols, 2018) reveals textiles as objects that contributed to the projection of urban social status and the cultural construction of political authority by medieval rulers.

After completing my AHRC funded doctoral studies at the University of Glasgow in 2009, I worked as a Teaching Fellow in Medieval History at the University of St Andrews, 2009-2010 and as a Lecturer in Medieval History at the University of York 2010-2012, before being appointed as Lecturer in Medieval History at Chester in 2012.

Do you have a question for Katherine and Thomas?

Write it in the comments box below and Katherine and Thomas will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

Read about how researchers are helping pre-service teachers to make STEM learning more engaging:

www.futurumcareers.com/how-can-we-make-stem-subjects-more-engaging-for-students

0 Comments