How can urban planners and architects reduce inequality in cities?

As cities grow, what happens to individual neighbourhoods within them? This is what the Centre for Sustainable, Healthy and Learning Cities and Neighbourhoods hopes to find out. Led by Professor Ya Ping Wang at the University of Glasgow, UK, this collaboration brings together architects such as Dr Josephine Malonza at the University of Rwanda and urban planners such as Dr Shilpi Roy at Khulna University, Bangladesh, to explore how to improve urban environments.

TALK LIKE AN URBAN STUDIES RESEARCHER

AKARUBANDA – the traditional Rwandan concept of public open space

PULL FACTOR – something that encourages someone to move towards an area

PUSH FACTOR – something that encourages someone to move away from an area

URBAN SPRAWL – the rapid spatial expansion of a city due to unplanned, uncontrolled and scattered growth

URBANISATION – the proportional increase of population living in urban areas compared to rural areas

By 2030, the United Nations predicts that 60% of the world’s population will live in cities. While cities can provide residents with services and employment opportunities, rapid unplanned urban growth means these advantages are not available to everyone. “Cities are very complex,” explains Professor Ya Ping Wang of the University of Glasgow. He is the director of the Centre for Sustainable, Healthy and Learning Cities and Neighbourhoods (SHLC), an international research collaboration that hopes to better understand this complexity.

The SHLC team is studying urban neighbourhoods in 14 cities in Africa and Asia, including Kigali and Huye in Rwanda, and Dhaka and Khulna in Bangladesh. Team members have a wide range of urban studies-related backgrounds, from urban planning, such as Dr Shilpi Roy at Khulna University, to architecture, such as Dr Josephine Malonza at the University of Rwanda, and from health to education. Their research will unpack the challenges of urbanisation and support the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, not only to ensure cities and communities are sustainable, but also to ensure those living in urban environments have good health and well-being, and access to quality education.

WHY ARE CITIES GROWING?

Cities offer opportunities for employment and social interaction, enticing migrants to urban centres, while poverty commonly drives migrants from rural regions. “In Bangladesh, unequal land distribution, inadequate education and healthcare, unemployment and displacement by natural disasters all act as push factors, forcing rural residents to leave,” explains Shilpi. “Urban industries, income opportunities, better social amenities and improved livelihoods in cities all act as pull factors to draw rural people to urban areas.”

Cities also expand in response to growing national populations. “The rapid urbanisation we are currently seeing in Rwanda is primarily fuelled by the high birth rate and resulting phenomenal increase of the country’s population,” says Josephine.

WHAT PROBLEMS ARE CAUSED BY URBANISATION?

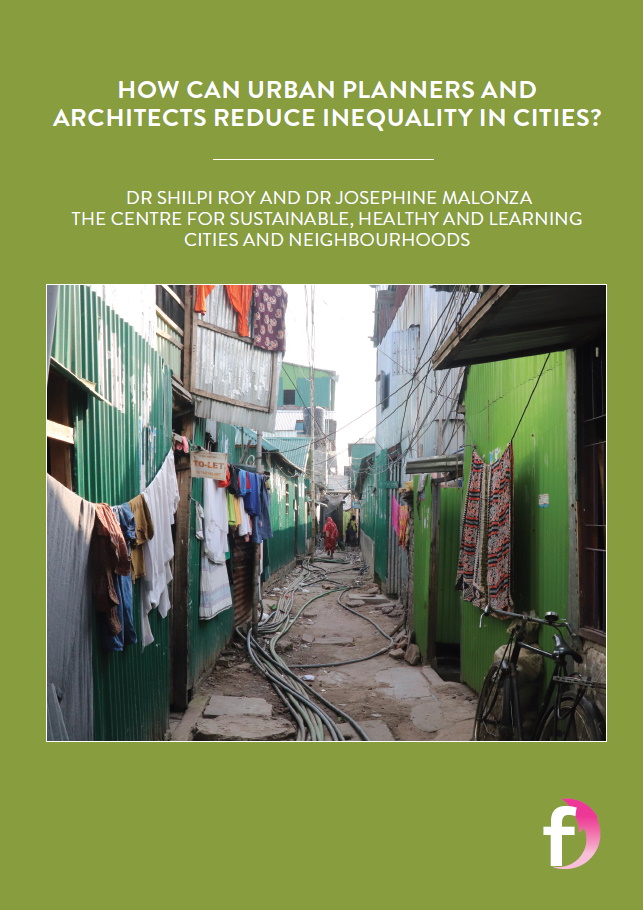

Overcrowding, pollution, congestion, urban sprawl, overuse of resources and lack of access to amenities are just some of the problems caused by urbanisation. In Bangladesh, the number of slums has increased almost five-fold since 1997 as more people move to the cities, and over one in five urban residents live in poverty, highlighting how rapid urbanisation commonly leads to increased social inequality.

At the same time, cities generate large amounts of waste, which can end up in waterways or in the air that people breathe. Over half of all solid waste produced in Khulna is dumped on the roadside. “Unplanned urbanisation in the cities of Bangladesh has led to crowded and polluted living conditions, with urban services insufficient to serve the communities that live there,” says Shilpi. Air pollution can have serious consequences not just for human health but for education. In 2021, schools were closed in the Indian capital of Delhi due to record levels of air pollution.

WHAT METHODS ARE THE SHLC TEAM USING?

Although urban sustainability is often discussed at city-level, the diversity within a single city means broad generalisations lose the intricacies of city life. The SHLC is investigating cities at a neighbourhood-scale to address this issue. “We carry out large-scale household surveys and focus group interviews in different types of neighbourhoods,” says Professor Michele Schweisfurth, from the University of Glasgow. She is a professor of comparative and international education and a co-investigator in the SHLC team. “This helps us to understand neighbourhood characteristics, including the demographic, social and economic composition of different districts within a single city.”

Team members also statistically analyse official datasets to quantify urban growth and urban inequality. They use satellite imagery and visual observations to map out urban expansion and land-use change. And they review urban policy documents to explore how development is viewed and managed in the case-study cities.

WHAT DO NEIGHBOURHOODS NEED?

For a neighbourhood to be considered a ‘sustainable, healthy and learning environment’, all residents within it should have access to educational, employment and healthcare opportunities. “The presence of affordable, quality and adequate facilities for all increases the living conditions of a neighbourhood’s residents,” explains Shilpi. “If development opportunities are integrated in a neighbourhood, people commute lesser distances to access work, healthcare and education,” says Josephine. “If a neighbourhood is vibrant, this will encourage healthy lifestyles, employment opportunities and economic growth.”

Sustainable neighbourhoods should also reduce their impact on the natural environment. This requires efficient public transport services to reduce dependence on private cars and waste management services to prevent rubbish being dumped on streets and in waterways.

It is also incredibly important for urban neighbourhoods to contain open, unbuilt areas, such as parks. “Public open spaces are lifelines for communities,” explains Josephine. “They help to improve our social, physical and mental health – all of the things which give life meaning.” In Rwanda, there is a traditional concept of public space known as akarubanda. Shared social spaces in rural settlements provide opportunities for community members to gather and socialise, dance, share food and exchange words of wisdom. Through her research and engagement with policy makers, Josephine hopes to bring akarubanda back into contemporary Rwandan cities.

HOW COULD URBAN DEVELOPMENT POLICIES IMPROVE CITIES?

“More attention needs to be paid to improving city planning and regulation, especially prioritising neighbourhood-based development,” Shilpi says. “This is necessary to deal with inequalities and the lack of services in growing urban areas.” She and Josephine both advocate for improved urban development policies in their countries. These policies need a bottom-up approach, driven by community members and the needs of individual neighbourhoods, to ensure new urban development serves the people of the city.

Urban sprawl is a significant challenge in Rwanda and Bangladesh as informal settlements grow around cities. Josephine suggests a solution could be to create urban qualities (such as services and employment opportunities) in rural settlements, thereby minimising rural to urban migration and so reducing the pressure on cities. Shilpi hopes to see unified urban governance in Bangladesh, in which all the different agencies involved in city management work together to regulate development. She also highlights that all development policies should consider the environmental impact of urbanisation and industrialisation.

The research findings from the SHLC are already being communicated with stakeholders. Shilpi and the Bangladesh team have shared their results with the mayors of Dhaka and Khulna and are now preparing policy briefs based on SHLC findings to ensure national urban policies promote sustainable, healthy and learning neighbourhoods. Josephine and the Rwandan team have met with stakeholders to plan how new policies can be implemented, and Josephine has been appointed to a joint sector review board at the Ministry of Infrastructure and a technical advisory group for the city of Kigali, where she can apply her research findings at government level.

The members of the SHLC are not only helping us understand cities in greater detail but are using their expertise to improve our urban environments. As Shilpi comments, “With a career in urban studies, you can really make a difference in the world!”

THE CENTRE FOR SUSTAINABLE, HEALTHY AND LEARNING CITIES AND NEIGHBOURHOODS (SHLC)

PARTNER INSTITUTIONS: University of Glasgow, UK; Khulna University, Bangladesh; University of Rwanda, Rwanda; Human Sciences Research Council, South Africa; University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa; Ifakara Health Institute, Tanzania; National Institute of Urban Affairs, India; University of the Philippines, Philippines; Nankai University, China

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Urban Studies

RESEARCH PROJECT: Investigating the sustainability of cities and urban neighbourhoods by assessing residents’ access to healthcare, education and opportunities

FUNDERS: UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF)

ABOUT URBAN STUDIES

The world is rapidly urbanising. As people flock to cities in search of employment opportunities, urban populations are increasing faster than ever. As cities expand to accommodate this influx of migrants, urban planning has never been more important.

WHY DO CITIES NEED TO BE PLANNED?

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM232

AKARUBANDA – the traditional Rwandan concept of public open space

PULL FACTOR – something that encourages someone to move towards an area

PUSH FACTOR – something that encourages someone to move away from an area

URBAN SPRAWL – the rapid spatial expansion of a city due to unplanned, uncontrolled and scattered growth

URBANISATION – the proportional increase of population living in urban areas compared to rural areas

By 2030, the United Nations predicts that 60% of the world’s population will live in cities. While cities can provide residents with services and employment opportunities, rapid unplanned urban growth means these advantages are not available to everyone. “Cities are very complex,” explains Professor Ya Ping Wang of the University of Glasgow. He is the director of the Centre for Sustainable, Healthy and Learning Cities and Neighbourhoods (SHLC), an international research collaboration that hopes to better understand this complexity.

The SHLC team is studying urban neighbourhoods in 14 cities in Africa and Asia, including Kigali and Huye in Rwanda, and Dhaka and Khulna in Bangladesh. Team members have a wide range of urban studies-related backgrounds, from urban planning, such as Dr Shilpi Roy at Khulna University, to architecture, such as Dr Josephine Malonza at the University of Rwanda, and from health to education. Their research will unpack the challenges of urbanisation and support the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, not only to ensure cities and communities are sustainable, but also to ensure those living in urban environments have good health and well-being, and access to quality education.

WHY ARE CITIES GROWING?

Cities offer opportunities for employment and social interaction, enticing migrants to urban centres, while poverty commonly drives migrants from rural regions. “In Bangladesh, unequal land distribution, inadequate education and healthcare, unemployment and displacement by natural disasters all act as push factors, forcing rural residents to leave,” explains Shilpi. “Urban industries, income opportunities, better social amenities and improved livelihoods in cities all act as pull factors to draw rural people to urban areas.”

Cities also expand in response to growing national populations. “The rapid urbanisation we are currently seeing in Rwanda is primarily fuelled by the high birth rate and resulting phenomenal increase of the country’s population,” says Josephine.

WHAT PROBLEMS ARE CAUSED BY URBANISATION?

Overcrowding, pollution, congestion, urban sprawl, overuse of resources and lack of access to amenities are just some of the problems caused by urbanisation. In Bangladesh, the number of slums has increased almost five-fold since 1997 as more people move to the cities, and over one in five urban residents live in poverty, highlighting how rapid urbanisation commonly leads to increased social inequality.

At the same time, cities generate large amounts of waste, which can end up in waterways or in the air that people breathe. Over half of all solid waste produced in Khulna is dumped on the roadside. “Unplanned urbanisation in the cities of Bangladesh has led to crowded and polluted living conditions, with urban services insufficient to serve the communities that live there,” says Shilpi. Air pollution can have serious consequences not just for human health but for education. In 2021, schools were closed in the Indian capital of Delhi due to record levels of air pollution.

WHAT METHODS ARE THE SHLC TEAM USING?

Although urban sustainability is often discussed at city-level, the diversity within a single city means broad generalisations lose the intricacies of city life. The SHLC is investigating cities at a neighbourhood-scale to address this issue. “We carry out large-scale household surveys and focus group interviews in different types of neighbourhoods,” says Professor Michele Schweisfurth, from the University of Glasgow. She is a professor of comparative and international education and a co-investigator in the SHLC team. “This helps us to understand neighbourhood characteristics, including the demographic, social and economic composition of different districts within a single city.”

Team members also statistically analyse official datasets to quantify urban growth and urban inequality. They use satellite imagery and visual observations to map out urban expansion and land-use change. And they review urban policy documents to explore how development is viewed and managed in the case-study cities.

WHAT DO NEIGHBOURHOODS NEED?

For a neighbourhood to be considered a ‘sustainable, healthy and learning environment’, all residents within it should have access to educational, employment and healthcare opportunities. “The presence of affordable, quality and adequate facilities for all increases the living conditions of a neighbourhood’s residents,” explains Shilpi. “If development opportunities are integrated in a neighbourhood, people commute lesser distances to access work, healthcare and education,” says Josephine. “If a neighbourhood is vibrant, this will encourage healthy lifestyles, employment opportunities and economic growth.”

Sustainable neighbourhoods should also reduce their impact on the natural environment. This requires efficient public transport services to reduce dependence on private cars and waste management services to prevent rubbish being dumped on streets and in waterways.

It is also incredibly important for urban neighbourhoods to contain open, unbuilt areas, such as parks. “Public open spaces are lifelines for communities,” explains Josephine. “They help to improve our social, physical and mental health – all of the things which give life meaning.” In Rwanda, there is a traditional concept of public space known as akarubanda. Shared social spaces in rural settlements provide opportunities for community members to gather and socialise, dance, share food and exchange words of wisdom. Through her research and engagement with policy makers, Josephine hopes to bring akarubanda back into contemporary Rwandan cities.

HOW COULD URBAN DEVELOPMENT POLICIES IMPROVE CITIES?

“More attention needs to be paid to improving city planning and regulation, especially prioritising neighbourhood-based development,” Shilpi says. “This is necessary to deal with inequalities and the lack of services in growing urban areas.” She and Josephine both advocate for improved urban development policies in their countries. These policies need a bottom-up approach, driven by community members and the needs of individual neighbourhoods, to ensure new urban development serves the people of the city.

Urban sprawl is a significant challenge in Rwanda and Bangladesh as informal settlements grow around cities. Josephine suggests a solution could be to create urban qualities (such as services and employment opportunities) in rural settlements, thereby minimising rural to urban migration and so reducing the pressure on cities. Shilpi hopes to see unified urban governance in Bangladesh, in which all the different agencies involved in city management work together to regulate development. She also highlights that all development policies should consider the environmental impact of urbanisation and industrialisation.

The research findings from the SHLC are already being communicated with stakeholders. Shilpi and the Bangladesh team have shared their results with the mayors of Dhaka and Khulna and are now preparing policy briefs based on SHLC findings to ensure national urban policies promote sustainable, healthy and learning neighbourhoods. Josephine and the Rwandan team have met with stakeholders to plan how new policies can be implemented, and Josephine has been appointed to a joint sector review board at the Ministry of Infrastructure and a technical advisory group for the city of Kigali, where she can apply her research findings at government level.

The members of the SHLC are not only helping us understand cities in greater detail but are using their expertise to improve our urban environments. As Shilpi comments, “With a career in urban studies, you can really make a difference in the world!”

THE CENTRE FOR SUSTAINABLE, HEALTHY AND LEARNING CITIES AND NEIGHBOURHOODS (SHLC)

PARTNER INSTITUTIONS: University of Glasgow, UK; Khulna University, Bangladesh; University of Rwanda, Rwanda; Human Sciences Research Council, South Africa; University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa; Ifakara Health Institute, Tanzania; National Institute of Urban Affairs, India; University of the Philippines, Philippines; Nankai University, China

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Urban Studies

RESEARCH PROJECT: Investigating the sustainability of cities and urban neighbourhoods by assessing residents’ access to healthcare, education and opportunities

FUNDERS: UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF)

ABOUT URBAN STUDIES

The world is rapidly urbanising. As people flock to cities in search of employment opportunities, urban populations are increasing faster than ever. As cities expand to accommodate this influx of migrants, urban planning has never been more important.

WHY DO CITIES NEED TO BE PLANNED?

“Planning is important as it helps cities to develop strategically, based on existing resources and a well envisioned future,” Josephine explains. “Without this balance, cities would outrun their resources and end up in a complete mess.”

WHAT ARE THE HIGHLIGHTS OF WORKING IN URBAN STUDIES?

“I am passionate about the quality of life in urban areas, and hence unpacking the multifaceted layers that urban societies have to navigate to enjoy life in cities,” says Josephine. Working in urban design as well as architecture provides her with a wider perspective, giving her a deeper understanding of social life in the unbuilt parts of cities that architects do not necessarily engage with.

Shilpi is motivated by knowing her expertise in urban planning can promote equality in urban areas. “Rapid urbanisation leads to pollution, environmental degradation and inequality,” she says. “Urban planning has immense scope for tackling these urban challenges and securing a sustainable future for urban residents.”

EXPLORE A CAREER IN URBAN STUDIES

• Visit the Centre for Sustainable, Healthy and Learning Cities and Neighbourhoods to learn how experts in urban studies and related fields are applying their skills to improve urban environments around the world: www.centreforsustainablecities.ac.uk

• Josephine says that urban studies will enable you to explore the past, present and future of cities with humans at their centre. “A range of career pathways will allow you to impact sustainable cities by engaging with their economical, environmental and cultural trends.”

• As an urban planner, you could design new neighbourhoods or redevelop existing ones. As an architect, you could design the buildings and infrastructure needed in these new developments.

• Prospects provides information about what you could do with a degree in urban planning (www.prospects.ac.uk/careers-advice/what-can-i-do-with-my-degree/urban-planning) or architecture (www.prospects.ac.uk/careers-advice/what-can-i-do-with-my-degree/architecture).

• The International Society of City and Regional Planners works in over 90 countries to help make cities safe, resilient and sustainable: www.isocarp.org

• The International Union of Architects provides information about the collaborative role that architects can play in addressing the UN Sustainable Development Goals: www.uia-architectes.org/webApi/en

• Shilpi highlights that it is useful to study both science and arts subjects at school if you are interested in pursuing a career in urban studies. She notes that students with a strong mathematics background will have more opportunities in the field, and Josephine also recommends studying geography and physics.

• University degrees in urban studies, urban planning, architecture and human geography will all allow you to explore the role of architecture and society in urban environments.

• At university, Josephine recommends taking modules in urban design, environmental design, urban geography and urban anthropology, while Shilpi recommends modules in Geographical Information Systems (GIS), remote sensing and transportation planning.

HOW DID JOSEPHINE BECOME AN ARCHITECT?

DR JOSEPHINE MALONZA IS A LECTURER IN THE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE AND THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT AT THE UNIVERSITY OF RWANDA.

FIELDS OF RESEARCH: ARCHITECTURE, URBAN DESIGN

As a young child, I hated seeing girls playing ‘cooking’ and boys playing with toy cars. I wanted to see girls playing with more technical things, like the boys did. When I was 15, I decided I wanted to be an architect. I studied hard in STEM subjects at school and had the opportunity to study architecture at university.

I was one of only two female students in my architecture class at university. I was a curious student but did not have any female role models in the School of Architecture. This inspired me to become a lecturer so that I could be a role model for girls in the future. My seriousness of purpose in teaching and mentoring students saw me appointed as the dean of the school when I was only 31 years of age.

Architecture and society have a complex relationship. For architecture to be understood by society, society has to form a central part of it. For this reason, I have changed the way I teach architecture and urban design. My modules are now more participatory and my students interact with communities and live sites. Last year, my class conducted a successful community workshop towards finding an innovative solution to informal housing in Kigali.

My research has initiated several stakeholder engagement activities where national policy has been discussed and plans for implementation have been mapped out. I have also been appointed to several boards in the city of Kigali and at Rwanda’s Ministry of Infrastructure, where pressing urban development dynamics are tackled.

Seeing how proper architectural education can transform societies keeps me engaged and motivated in my job. The kind words of appreciation that I receive each week – especially from my students and school alumni – keep me fuelled to do more.

HOW DID SHILPI BECOME AN URBAN PLANNER?

DR SHILPI ROY IS AN ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF URBAN AND RURAL PLANNING AT KHULNA UNIVERSITY IN BANGLADESH.

FIELDS OF RESEARCH: PLANNING POLICY, URBAN GROWTH, NEIGHBOURHOOD PLANNING

At an early age, I was interested in drawing, designing, and building models of houses. During secondary school, I found three mentors through family networks who were studying architecture and urban planning. I had the option to study either subject at university but chose to pursue urban planning based on the better job prospects in this field in Bangladesh.

Many of my family members work in academia, so an academic career in urban planning appealed to me. After graduation, I decided to prepare myself for this career. I studied a master’s in Spatial Planning at Oxford Brookes University in the UK, then I attended the University of Manchester for my PhD in Planning and Landscape.

I feel privileged to have had this opportunity to access higher education. Public funds covered all my education-related expenses in Bangladesh. I therefore have a sense of social responsibility to pay this back to my country through my work.

I have worked for city development authorities and NGOs such as Action Aid to address the challenges facing urban neighbourhoods in Bangladesh. I would not have had the opportunity to do so without a planning background and specialised degree in planning and regeneration.

As the leader of the SHLC in Bangladesh, I am responsible for coordinating the research, capacity building activities, management and impact activities in the country. The scope of the SHLC project is immense and has given me the chance to work with partners across Asia and Africa. By the end of the project, we will have a good understanding of what makes a neighbourhood sustainable and thus be able to guide policymakers in this direction.

JOSEPHINE AND SHILPI’S TOP TIPS

01 Work hard: dreams don’t work unless we work.

02 Focus on positive inspiration, the world is full of possibilities and surprises.

03 Read widely; for instance, you can learn about urban planning by reading books on everything from classic civilisation to the urban reform movement of the 20th century.

Write it in the comments box below and Josephine or Shilpi will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

Hello, i am currently doing a college research project into whether urban planning mitigates or worsens social inequality and id like to ask a few questions if possible.

What strategies do urban planners use to increase the availability of affordable housing in urban areas?

What measures can urban planners take to prevent gentrification from displacing low-income residents?

Your insights would be incredibly helpful, thank you.

I think I can answer you, In America there is something called the missing middle where there is skyscrapers and then a block later you find single family homes. Urban planners like to invest in midrises, duplexes, and other forms of housing. With gentrification, urban planners do lots of studying to projects that are big and cause displacement.