How philosophers have influenced the way you think about race

Problematic perceptions about race damage our society. These attitudes can seem impossible to overcome, but philosophers Dr Jennifer Mensch, at Western Sydney University in Australia, and Dr Michael Olson, at Marquette University in the US, beg to differ. They are compiling a collection of 18th-century philosophical and scientific texts that helped shape the way people saw race across the Western world, and were used to justify colonisation. They believe that by exposing these historical roots of racism, opportunities to improve societal attitudes to race will become easier to identify.

TALK LIKE A HISTORIAN AND PHILOSOPHER OF SCIENCE

Biological racism — prejudice against people based on the mistaken belief that ‘race’ is a part of a person’s biology and indicates race-specific traits like intelligence or work ethic

Heredity — genetically passing on characteristics from biological parent to child. In the 18th century, where a person came from was thought to determine some of the features they inherited and passed on to their children

Implicit bias — to be unaware of negative attitudes you might hold toward others, especially if you got these ideas from everyday cultural products, like films or television

Philosophy — the study of the nature of knowledge, reality, ethics, history and politics

Racialised groups — a modern term for what used to be called ‘race’, that highlights the ways in which racial identities are socially-imposed rather than natural

Structural racism — policies and rules that contribute to the inequality of racialised groups

“Race is one of the most important concepts in modern social life,” says Dr Michael Olson, a philosopher at Marquette University. “It’s also among the most poorly understood, at least in part because it can be so uncomfortable to talk about it.” We all have a rough understanding of the roots of racial inequality, including the huge injustices of colonisation and slavery, and their impacts today. However, what is less well-understood is why, and how, such ideas about race arose in the first place. “We are bringing our expertise, as philosophers interested in the history and philosophy of science, to help understand these origins,” says Dr Jennifer Mensch at Western Sydney University, explaining the research she and Michael are conducting.

Throughout history, philosophers have paved the way for shifts in societal thought, but nowadays their works and ideas are typically analysed apart from the context in which they were written. “This is a mistake, because these philosophers were heavily influenced by the economic and political realities of their day,” explains Jennifer.

Correcting this oversight is the key focus of Jennifer and Michael’s project: creating an anthology (or collection) of 18th-century philosophical and scientific works. Their research will consider cultural context to assess how the works influenced, and were influenced by, societal attitudes to race.

The European Age of Enlightenment

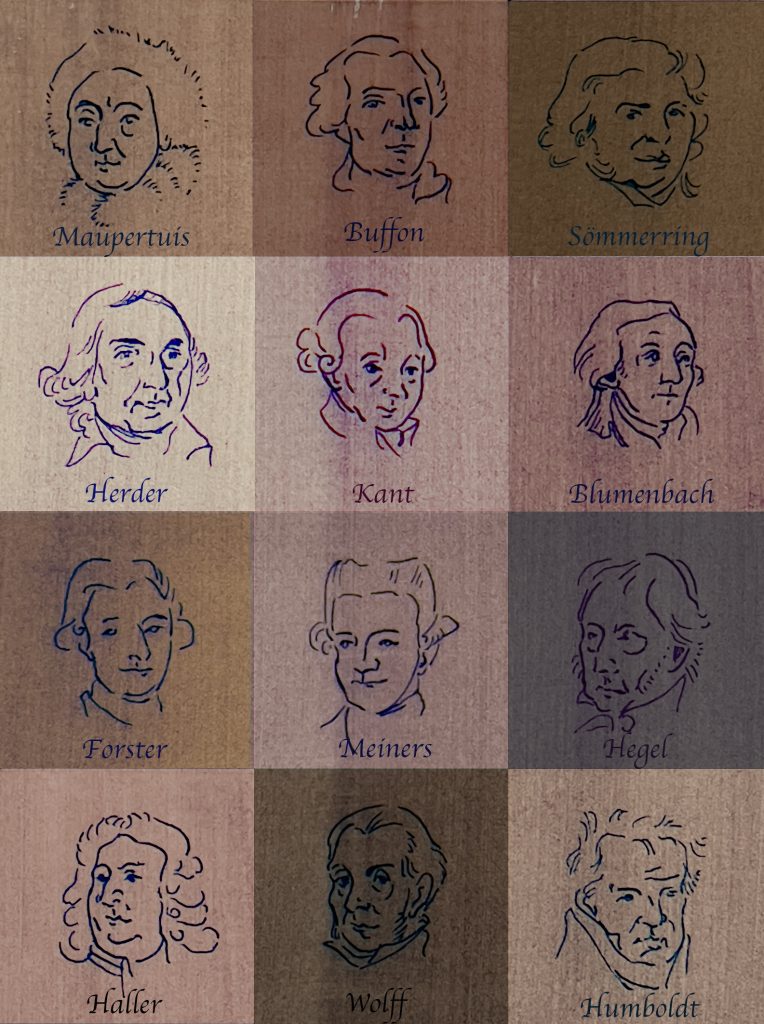

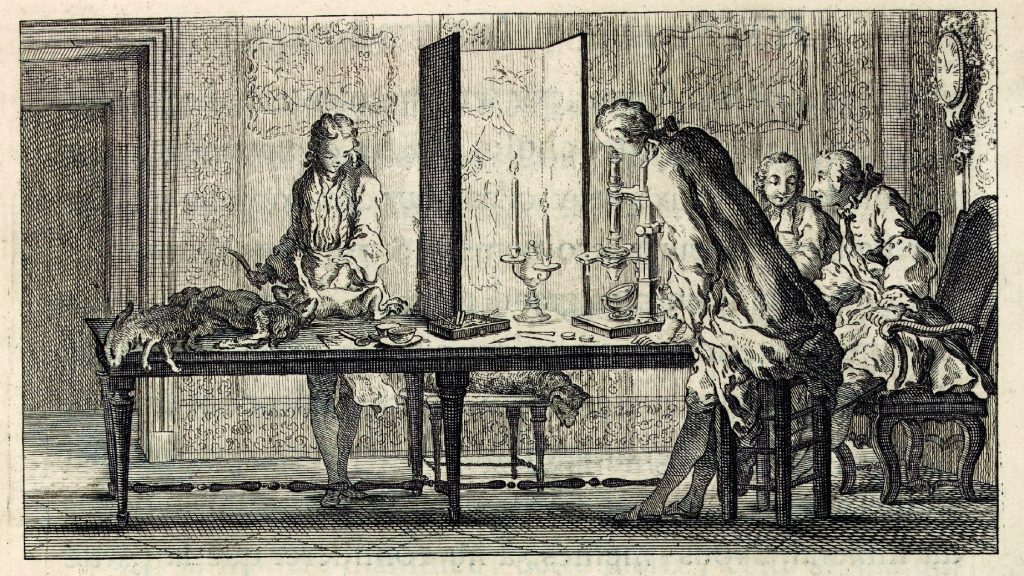

Jennifer and Michael’s anthology will focus on philosophers and scientists working in Germany between 1745 and 1845. Sometimes referred to as the ‘Age of Enlightenment’, this period in the 18th and 19th centuries marks a time when European thinkers promoted the pursuit of knowledge through reason and evidence – this was the beginning of what we now call the scientific method.

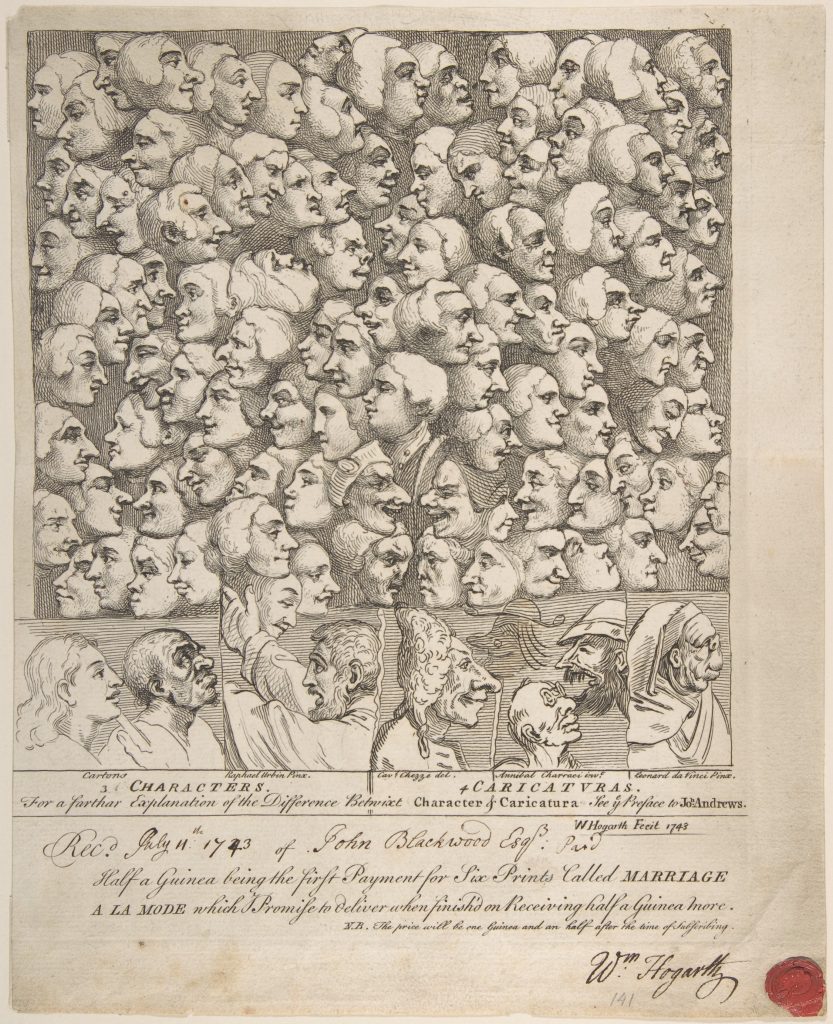

One of the aims of the Enlightenment was to organise information in a rational way. For example, many dictionaries and encyclopaedias were written during this period to classify and sort information about animals, plants, minerals, diseases and medicines. At the same time, European powers (especially England, France and Spain) were exploring the world in search of resources and new places to establish colonies. As a result, Europeans were suddenly aware of the many different cultures and peoples living very different lives far away from the shores of Europe. This created a desire to classify what was called, at the time, ‘the varieties of mankind’. Classification in this area laid the basis for the creation of a scientific theory of human differences, eventually referred to as ‘race’.

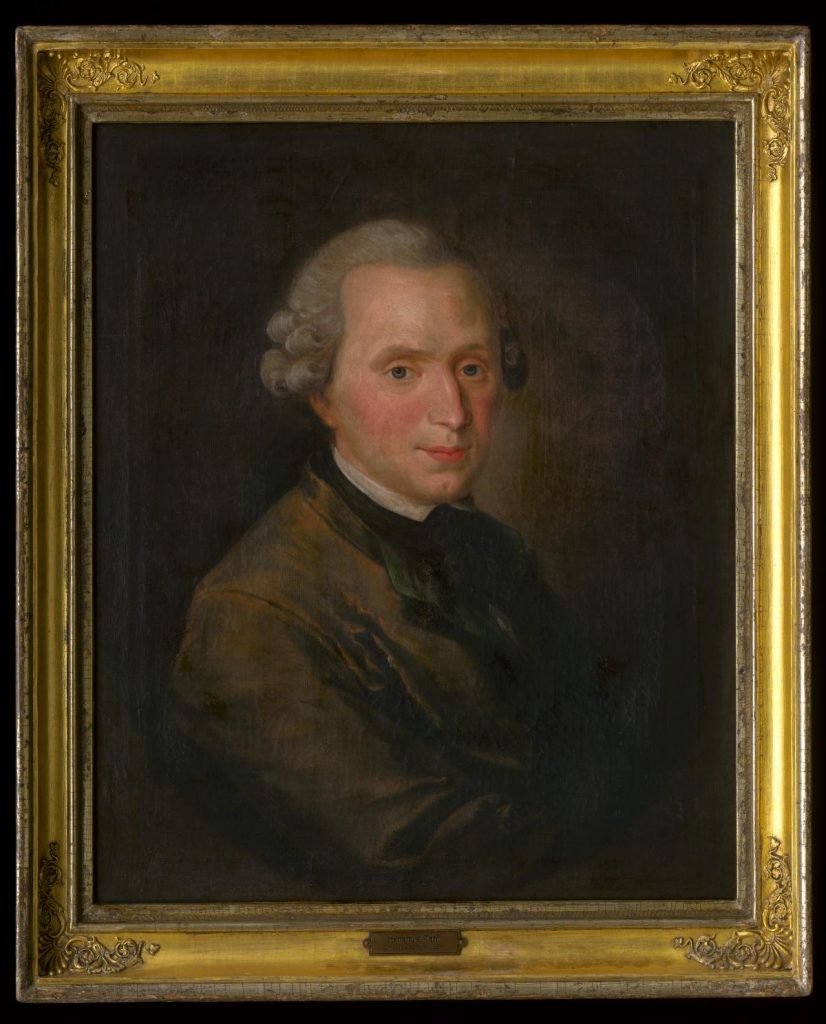

Kant’s views on race

Jennifer and Michael’s anthology will pay special attention to the works of German Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804). Kant is often described as the most important philosopher of the 18th century, and his ideas about morality continue to be admired and followed in Western society. However, he also used Enlightenment thinking to put forward his own account of the ‘scientific’ basis for racial differences. “Kant focused on skin colour as the primary way to categorise race, and he linked different races to certain characteristics,” says Jennifer. “For example, Kant thought that Europeans were the most capable of industry and self-improvement, while he considered races found closer to the equator to be ‘lazy’.”

For Kant, rationality combined with responsibility was the hallmark of human life. Races considered less rational were deemed ‘inferior’ – and, according to Kant’s theory, were easily identified by skin colour. “This approach supported colonisation as a project aimed at advancing human progress and as requiring, therefore, that colonisers should ‘civilise’ the ‘less advanced races’,” explains Michael. “Kant’s attempt to link skin colour to other characteristics, such as intelligence, motivation and the ability to govern one’s own society, influenced many other studies from that time onwards.”

The beginnings of ideas

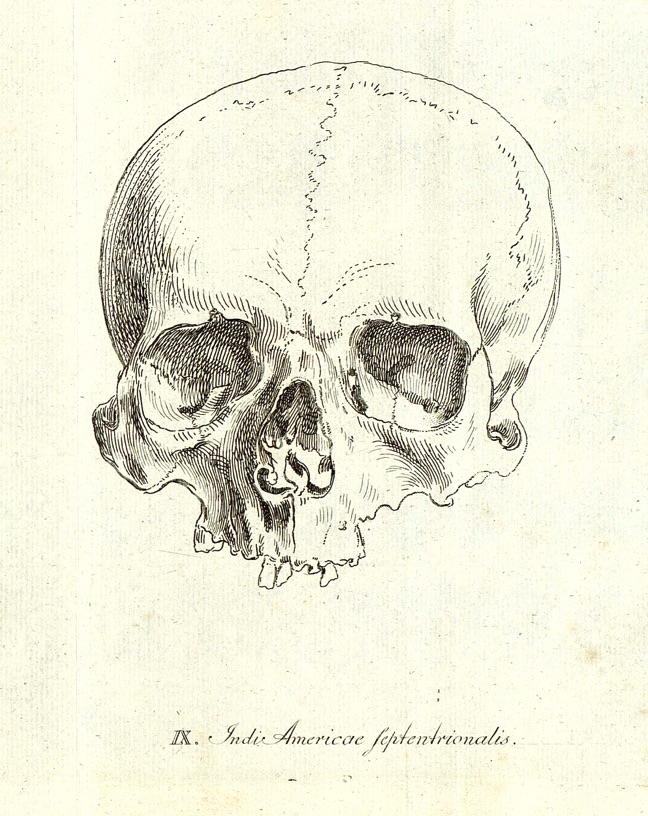

While Kant’s ideas about race have been scientifically disproven and are heavily criticised today, their influence persists. To understand both why this is, and how to combat it, Jennifer and Michael believe it is vital to understand the context in which these ideas arose. Their anthology will consist of three parts. The first will focus on the work of scientists and philosophers to understand the processes of generation and inheritance. The second part will consist of the attempts at the time, including by Kant, to understand and categorise racial differences. The third part will focus on the social and historical context: most importantly, the effects of empires, colonisation and slavery, as well as the ‘evidence’ gathered by 18th-century scientists, such as skulls, from other parts of the world.

The first part, focusing on the history of science, is crucial to understanding the attempts of 18th-century scientists and philosophers to fit things into neat categories. “At the time, it was still not well understood how the sperm and egg contributed to the generation of offspring,” explains Michael. “The children of parents of different races provided key evidence that both sperm and egg contributed, given these children’s skin colour typically demonstrates inheritance from both biological parents.” Enlightenment scientists and philosophers also questioned the degree to which skin colour is determined by the environment. During this time-period of colonisation and slavery, people wondered if Europeans moving to Australia or Africans moving to the Americas would eventually produce descendants who looked like the peoples native to the land. “Though biologists have now definitively rejected the idea of race as a scientific category for classifying people, questions around inherited and cultural differences between racialised groups endure in politics across the world,” says Jennifer.

Racism today

“Examples of structural racism in modern history are easy to find,” says Jennifer. “For instance, the US’s post-World War II social security scheme guaranteed pensions, but not for agricultural labourers or domestic servants. At the time, these were the two main professions of non-white people.” Generations later, such prejudiced policies continue to have an impact. “In the 1950s, US banks were reluctant to give mortgages to Black buyers, which has directly led to today’s wealth gap in the US,” Jennifer explains. “White families continue to be richer, on average, than Black families, typically with money inherited through the sale of the houses owned by their grandparents and parents.”

It is not just policies, but also internalised prejudices, that carry forward such inequalities. Though few people would describe themselves as racist, there is compelling evidence that racism is often unconscious, and that this kind of prejudice, or ‘implicit bias’, is widespread. Implicit bias occurs because life is full of cultural messages telling us how to think about ourselves (e.g., ‘This is what girls do’) and about other people (e.g., ‘Foreigners eat strange food’). As a result, we generate and act upon stereotypes without realising it. This is problematic and damaging, as stereotypes are not accurate representations of individuals.

While people might know that structural racism and implicit bias exist, their historical and philosophical roots are less thoroughly understood, which is one reason why Jennifer and Michael believe they persist. “When people are educated about how these sociocultural categories have come into being, they can be released from identities that can seem biologically determined,” says Jennifer. “In fact, this categorisation only occurred in fairly recent history, and this release is a good thing.”

Associate Professor Jennifer Mensch, School of Humanities and Communication Arts, Western Sydney University, Australia

Associate Professor Jennifer Mensch, School of Humanities and Communication Arts, Western Sydney University, Australia

Dr Michael Olson, Department of Philosophy, Marquette University, USA

Fields of research: Philosophy, History and Philosophy of Science

Research project: Creating an anthology of key texts from 18th-century life sciences and philosophy to assess the history of the concept of race

Funders: Australian Research Council (ARC; Discovery Project DP1903769), Journal of the History of Philosophy, Western Sydney University, Marquette University

About philosophy

The word ‘philosophy’ comes from Ancient Greek and means ‘the love of wisdom’. For thousands of years, philosophers have reflected on the nature of reality, the organisation of society, and the best way to live a good life, introducing new ideas which have influenced, and been influenced by, cultural context.

Philosophy is a wide-ranging discipline that challenges our fundamental ideas about the world and our own place within it. “Philosophy makes you think about things in new and surprising ways,” says Jennifer. Simple questions become incredibly in-depth and interesting when addressed from a philosophical point of view. “For instance, what defines our ideas of self and individuality? Is it our body, our mind, our collection of memories? Do you remain ‘you’ if you develop amnesia or a personality disorder, for instance? Spend time with a philosopher and you will soon be questioning all sorts of things you thought you knew for certain!”

The history and philosophy of science

Jennifer and Michael specialise in the history and philosophy of science. This typically involves looking at what philosophers had to say about a scientific topic, then analysing those conversations in the context of the history of science and their impact on the philosophers’ own philosophies. “For example, Kant had a theory of racial diversity,” says Jennifer. “We are investigating how Kant’s theory fits into the history of scientific discussions of this topic at the time, and how it affected Kant’s own philosophy.”

What skills do philosophers need?

“To study philosophy, it’s important to be open-minded and a patient reader,” says Michael. So, if you are interested in philosophy, get reading! “There are plenty of literary philosophers out there,” says Jennifer, who recommends the plays and short stories written by Jean-Paul Sartre and the works of ‘existentialist’ writers such as Dostoevsky, Camus and Kafka. “Even works of science fiction, from authors such as Philip K. Dick and Ursula Le Guin, have really valuable philosophical insights that help stretch our minds.”

Studying philosophy means reading philosophical works written hundreds or even thousands of years ago. “It’s important to remember the period of history these were written in and give the authors a chance to communicate what was important to them,” Jennifer says. “That unlocks great possibilities: now you can discover what Plato thought about the soul, what Locke thought would happen when money was invented, or why Kant thought we couldn’t rule out the possibility of life on other planets.”

We live in a world full of information, where people make unfounded claims about anything and everything. Philosophy teaches you to think and ask questions, preparing you to join the debate in this world of claims and counter-claims. “Our students graduate knowing how to read carefully and think deeply, and most of all to remain intellectually curious,” says Michael. “They learn to write and communicate with great clarity and can engage in creative problem solving. These are precisely the kind of ‘transferable skills’ that employers look for.”

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM424

Philosophers of the European Age of Enlightenment influenced the way we think about race

© Jessica Mensch

Pathway from school to philosophy

• It would be useful to study English or history at school to build your critical reading and writing skills.

• Many universities offer undergraduate degrees in philosophy. Requirements for getting onto these courses vary but are usually flexible about what subjects they look for.

• Philosophical thinking can open a deeper understanding of every field of study, so whatever your interests, taking a class or two in philosophy alongside your other studies will enhance your view of the world.

Explore careers in philosophy

• You can use the transferable skills you will gain during a philosophy degree in a huge range of careers. For example, journalism, advertising and public relations all require people who can think analytically and communicate clearly. If you are passionate about ethics and justice, you could use your philosophy knowledge in a career in law or politics.

• Marquette University’s Department of Philosophy has information about the value of a philosophy degree, as well as spotlights on work from undergraduates and faculty: www.marquette.edu/philosophy

• Western Sydney University aims to make university accessible for students from all backgrounds. Their Year 12 Student Info Hub provides detailed information about how university works, how to apply, and a range of study materials and opportunities to visit: www.westernsydney.edu.au/future/study/info-for-year-12-students

• Times Higher Education provides information about what you could do with a philosophy degree: www.timeshighereducation.com/student/subjects/what-can-you-do-philosophy-degree

• Jennifer notes that, while salaries for recent philosophy graduates may not initially be the highest, ten years after graduation an average philosophy graduate is earning close to US$100,000 year.

Meet Jennifer

As a kid, I liked animals and being outside, so I thought I might become a veterinarian. I was also a big reader and loved to find out the ‘why’ of things. That’s how I fell in love with the history of ideas, which is focused on understanding how people have approached the world and its processes at different times through history. This includes how we have thought about animals and their place in nature, so it combines my interests perfectly.

My own father was a philosophy professor, which naturally meant that I wanted nothing to do with the subject! However, my undergraduate degree required me to take a philosophy class. The first lesson involved Zeno’s paradoxes, which lit up something in my mind. After that, I never looked back and took every philosophy class I could.

I like studying 18th-century thinkers, especially because people didn’t have firm disciplinary boundaries back then. This meant that philosophers could cover everything from the fundamentals of knowledge, to ethics and logic, to geography and physics. Many were interested in new scientific technologies, like the microscope, and how these new devices caused us to radically change our ideas about reality and to ask questions about how our minds can come to know it.

The 18th century was also the ‘Age of Empire’, which has in the past been dismissed as irrelevant when considering philosophers of the time. However, this means you miss important facets of the philosopher’s perception of the world. I think it’s important to consider all cultural context, and not just pretend the bad stuff doesn’t exist. Philosophy requires asking hard questions.

I try to remain open-minded and intellectually curious. As well as being important skills for my profession, this has also helped me see the good in the world. I try to err on the side of generosity, and assume that most people are trying to do their best to navigate through a complex and confusing world with kindness.

Jennifer’s top tip

Create an ‘ideas journal’. If you hear or read something interesting, take a minute to write it down and think about it. Every time you hear a surprising way of approaching an issue, write it down. I’ve been keeping journals like these for decades, and they help me collect my thoughts and try out ideas. Philosophers have been doing similar things for hundreds of years!

Meet Michael

Growing up, I wanted to be a neurosurgeon or a filmmaker. But that was just because I hadn’t discovered philosophy yet!

My introduction to philosophy was an accident. I enrolled in a philosophy course as an undergraduate because my preferred courses were fully subscribed. However, when I discovered how philosophy encouraged intellectual curiosity and established connections between different disciplines, I was hooked.

There are ideas in the history of philosophy that seem strange or absurd when first encountered. I enjoy the challenge of working out why these unfamiliar ways of thinking seemed right to thoughtful people in the past. It’s an exercise in understanding how other people make sense of the world. Learning to see things as others see them is enormously helpful in clarifying the value of our own views and in appreciating the complexity and nuance of thought.

In a rapidly changing world, we often overlook how our lives and thoughts are often based on very old ideas. This connects us to ancient traditions and gives us a relationship with the past. More than that, we can understand the origins of our values, preconceptions and prejudices, which helps us understand which are useful and which should be discarded.

Everything is interesting and puzzling if you examine it closely enough. Once I realised how rewarding it can be to pay attention to the everyday things, I stopped thinking about how much better my life could be if I did something different or lived somewhere else. Finding value in philosophical reflection gives me a satisfaction that helps counteract the impulses of envy and ambition.

Do you have a question for Jennifer or Michael?

Write it in the comments box below and Jennifer or Michael will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

I just saw this today–great initiative, Jennifer and Mike! Very nice. And good luck moving forward.

Amazing work by these stellar philosophers. Delightful to see such erudite research being made accessible and available publicly.