What does adolescence look like for teenagers in England and Japan?

Our world may be home to many different cultures, but no matter where we are raised, the time we spend transitioning from children into adults is one of the most important stages of our lives. Dr Emily Emmott at University College London in the UK and Dr Masahito Morita at the University of Tokyo in Japan are looking at what is important to teenagers in different cultures as they go through adolescence. By asking teenagers in England and Japan to photograph their everyday lives for a week, the team has learned more about the social lives of teenagers, and how their experience of adolescence is shaped by their culture

TALK LIKE A BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGIST

ADOLESCENCE – a transition period between childhood and adulthood, associated with puberty, as well as changes to our roles and responsibilities

CULTURE – the customs, beliefs, habits, arts and social behaviour of a particular group of people

SOCIALITY – our ability as individuals to associate with other people in our communities

EVOLUTION – changes in the characteristics of living organisms over many generations, which help species to adapt to their surrounding environments

Adolescence is one of the most important periods of our lives. As we grow out of childhood, we are constantly surrounded with changes – to our bodies, to our roles and responsibilities, and even to the people we choose to spend time with. At the same time, changes in our brains make us suddenly very sensitive to what other people think about us, shaping our behaviour and development as we grow into adults. Yet even today, biologists are not completely sure why adolescence evolved in the first place!

The adolescent experience is not completely unique to humans; in nature, biologists have discovered similar stages in the lives of many animals. Because of this, some biological anthropologists think that adolescence has a key evolutionary advantage, which provides us with the crucial skills needed to survive and thrive as adults. In their research, biological anthropologists Dr Emily Emmott, from University College London, and Dr Masahito Morita, from the University of Tokyo, are studying this idea by exploring similarities and differences between the adolescence experienced by teenagers in England and Japan.

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM STUDYING ADOLESCENCE IN DIFFERENT CULTURES?

Across the world, humans have developed an array of different cultures. Although the culture we grow up in can have a strong influence over how we think and feel, we are all still human beings – and so there are many aspects of our behaviour, especially in adolescence, that are similar no matter where we are raised. “Every society has some kind of adolescence,” Emily says. “Common characteristics include interest in potential mates (girlfriends and boyfriends), exploring new things, developing new skills, and spending more time with friends instead of family.”

Emily proposes that by comparing the experience of adolescence between different cultures, biological anthropologists could learn more about how such an important stage of our lives first evolved, and how it impacts our future development. While any two cultures would be interesting to compare in this way, Emily chose to work with teenagers in England and Japan in particular. This is because she is half English and half Japanese, knows many people in both countries and understands both cultures very well. Working in collaboration, Emily and Masahito are now leading a fascinating study into what adolescence really means to teenagers in both countries.

HOW DID THE TEAM COLLECT DATA?

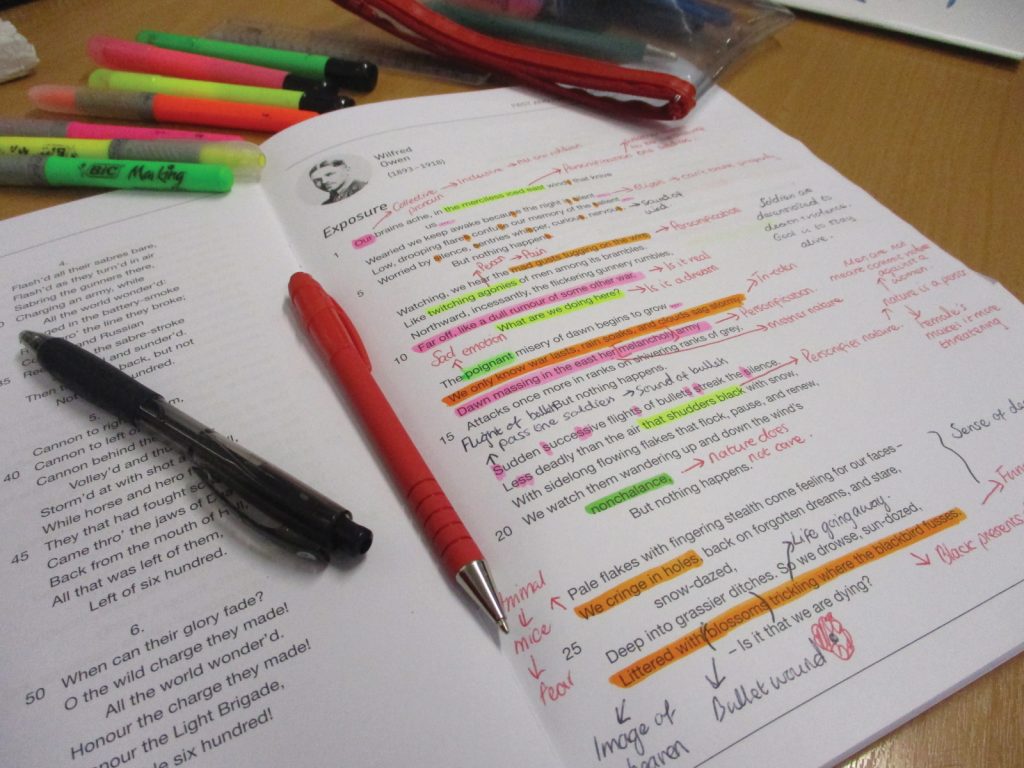

The key questions that Emily and Masahito wanted to ask were centred on the social lives of teenagers – such as who they hang out with, who they speak to, who supports them, and who they like and dislike. To collect this information, there are no people better qualified than teenagers themselves, and no better way to gather the data than taking photos of things important to them, which many teenagers already do every day.

In their study, Emily, Masahito and their colleagues asked students from different schools in England and Japan to capture their everyday lives on camera, over the course of a whole week. “We asked students between 13 and 15-years old to take photographs of important things, people and places in their lives,” Emily says. “Teenagers are experts of their own lives, so it was very important that we as researchers did not make assumptions about what’s important to teenagers.”

WHAT DISCOVERIES HAS THE TEAM MADE SO FAR?

Emily and Masahito’s team gained a lot of new information from the data. By studying the photographs, the team attained a fuller view of the social lives of teenagers in both countries – with common subjects including friends and family, pets, hobbies and nature. As studies have revealed in the past, the data suggest that adolescence in both England and Japan is crucial for gaining an identity and developing skills, and also for strengthening connections with our families, friends and wider communities.

At the same time, the team also noticed differences between the photos of teenagers in the two countries which they did not expect when the study started. “In England, many students communicated the importance of nature, and their pets were very important members of their family,” Emily says. “In Japan, students seemed to think more about their past and future, not just the important things in the present.”

As it draws conclusions from the similarities and differences they have found between the experience of adolescence in England and Japan, the team will soon present its discoveries to the wider research community. Yet, even when the research has been published, there will still be much more for the team to learn through future research.

HOW COULD THE RESEARCH BE EXPANDED IN THE FUTURE?

Already, the team is carrying out further studies to explore more specific aspects of adolescence in England and Japan. “My research student at UCL is investigating what 16 to 18-year-olds in London think about ‘femininity,’ and a PhD student at the University of Tokyo is investigating how peers and schools might impact girls’ sports participation,” Emily says.

Ultimately, the cultures of England and Japan are just a tiny fraction of all of the cultures we can find worldwide. In the future, Emily and Masahito’s team hopes to branch out to study how teenagers experience adolescence in other countries. By expanding the project further, the team could soon gain a more complete picture of how humans as a whole transition into adults, and perhaps even solve the evolutionary mystery of why adolescence emerged in the first place.

DR EMILY EMMOTT

DR EMILY EMMOTT

University College London, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Biological Anthropology

FUNDERS: Economic and Social Research Council, Arts and Humanities Research Council (Grant ref: ES/S013733/1)

DR MASAHITO MORITA

The University of Tokyo, Japan

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Evolutionary Anthropology, Human Behavioural Ecology

FUNDER: Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (Grant ref: JP17H06381)

ABOUT BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY

As a whole, anthropology is the study of everything that makes us human. Within this incredibly diverse field, biological anthropology studies the bodies, behaviours and evolution of human beings, our now-extinct hominin cousins, and other living primates, which are closely related to us on the evolutionary tree of life. Biological anthropologists draw from many different biological concepts in their research: from Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection, to the latest advances in psychology.

The field is split into many different branches: from bioarchaeology, which studies prehistoric human bones taken from archaeological digs; to evolutionary psychology, which explores how our minds have been shaped by the laws of natural selection. Biological anthropology is also an important part of human biology, which explores how our minds and bodies are shaped by aspects including anatomy, biochemistry and genetics.

WHAT IS REWARDING ABOUT THE FIELD?

Because biological anthropology is such a diverse area of research, Emily says that it can be really exciting to study. She could be reading about the hunting practices of ancient hunter-gatherers one day, brain development in children and adolescents the next day, and the lives of marmoset monkeys the day after that!

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM204

ADOLESCENCE – a transition period between childhood and adulthood, associated with puberty, as well as changes to our roles and responsibilities

CULTURE – the customs, beliefs, habits, arts and social behaviour of a particular group of people

SOCIALITY – our ability as individuals to associate with other people in our communities

EVOLUTION – changes in the characteristics of living organisms over many generations, which help species to adapt to their surrounding environments

Adolescence is one of the most important periods of our lives. As we grow out of childhood, we are constantly surrounded with changes – to our bodies, to our roles and responsibilities, and even to the people we choose to spend time with. At the same time, changes in our brains make us suddenly very sensitive to what other people think about us, shaping our behaviour and development as we grow into adults. Yet even today, biologists are not completely sure why adolescence evolved in the first place!

The adolescent experience is not completely unique to humans; in nature, biologists have discovered similar stages in the lives of many animals. Because of this, some biological anthropologists think that adolescence has a key evolutionary advantage, which provides us with the crucial skills needed to survive and thrive as adults. In their research, biological anthropologists Dr Emily Emmott, from University College London, and Dr Masahito Morita, from the University of Tokyo, are studying this idea by exploring similarities and differences between the adolescence experienced by teenagers in England and Japan.

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM STUDYING ADOLESCENCE IN DIFFERENT CULTURES?

Across the world, humans have developed an array of different cultures. Although the culture we grow up in can have a strong influence over how we think and feel, we are all still human beings – and so there are many aspects of our behaviour, especially in adolescence, that are similar no matter where we are raised. “Every society has some kind of adolescence,” Emily says. “Common characteristics include interest in potential mates (girlfriends and boyfriends), exploring new things, developing new skills, and spending more time with friends instead of family.”

Emily proposes that by comparing the experience of adolescence between different cultures, biological anthropologists could learn more about how such an important stage of our lives first evolved, and how it impacts our future development. While any two cultures would be interesting to compare in this way, Emily chose to work with teenagers in England and Japan in particular. This is because she is half English and half Japanese, knows many people in both countries and understands both cultures very well. Working in collaboration, Emily and Masahito are now leading a fascinating study into what adolescence really means to teenagers in both countries.

HOW DID THE TEAM COLLECT DATA?

The key questions that Emily and Masahito wanted to ask were centred on the social lives of teenagers – such as who they hang out with, who they speak to, who supports them, and who they like and dislike. To collect this information, there are no people better qualified than teenagers themselves, and no better way to gather the data than taking photos of things important to them, which many teenagers already do every day.

In their study, Emily, Masahito and their colleagues asked students from different schools in England and Japan to capture their everyday lives on camera, over the course of a whole week. “We asked students between 13 and 15-years old to take photographs of important things, people and places in their lives,” Emily says. “Teenagers are experts of their own lives, so it was very important that we as researchers did not make assumptions about what’s important to teenagers.”

WHAT DISCOVERIES HAS THE TEAM MADE SO FAR?

Emily and Masahito’s team gained a lot of new information from the data. By studying the photographs, the team attained a fuller view of the social lives of teenagers in both countries – with common subjects including friends and family, pets, hobbies and nature. As studies have revealed in the past, the data suggest that adolescence in both England and Japan is crucial for gaining an identity and developing skills, and also for strengthening connections with our families, friends and wider communities.

At the same time, the team also noticed differences between the photos of teenagers in the two countries which they did not expect when the study started. “In England, many students communicated the importance of nature, and their pets were very important members of their family,” Emily says. “In Japan, students seemed to think more about their past and future, not just the important things in the present.”

As it draws conclusions from the similarities and differences they have found between the experience of adolescence in England and Japan, the team will soon present its discoveries to the wider research community. Yet, even when the research has been published, there will still be much more for the team to learn through future research.

HOW COULD THE RESEARCH BE EXPANDED IN THE FUTURE?

Already, the team is carrying out further studies to explore more specific aspects of adolescence in England and Japan. “My research student at UCL is investigating what 16 to 18-year-olds in London think about ‘femininity,’ and a PhD student at the University of Tokyo is investigating how peers and schools might impact girls’ sports participation,” Emily says.

Ultimately, the cultures of England and Japan are just a tiny fraction of all of the cultures we can find worldwide. In the future, Emily and Masahito’s team hopes to branch out to study how teenagers experience adolescence in other countries. By expanding the project further, the team could soon gain a more complete picture of how humans as a whole transition into adults, and perhaps even solve the evolutionary mystery of why adolescence emerged in the first place.

DR EMILY EMMOTT

DR EMILY EMMOTT

University College London, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Biological Anthropology

FUNDERS: Economic and Social Research Council, Arts and Humanities Research Council (Grant ref: ES/S013733/1)

DR MASAHITO MORITA

The University of Tokyo, Japan

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Evolutionary Anthropology, Human Behavioural Ecology

FUNDER: Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (Grant ref: JP17H06381)

ABOUT BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY

As a whole, anthropology is the study of everything that makes us human. Within this incredibly diverse field, biological anthropology studies the bodies, behaviours and evolution of human beings, our now-extinct hominin cousins, and other living primates, which are closely related to us on the evolutionary tree of life. Biological anthropologists draw from many different biological concepts in their research: from Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection, to the latest advances in psychology.

The field is split into many different branches: from bioarchaeology, which studies prehistoric human bones taken from archaeological digs; to evolutionary psychology, which explores how our minds have been shaped by the laws of natural selection. Biological anthropology is also an important part of human biology, which explores how our minds and bodies are shaped by aspects including anatomy, biochemistry and genetics.

WHAT IS REWARDING ABOUT THE FIELD?

Because biological anthropology is such a diverse area of research, Emily says that it can be really exciting to study. She could be reading about the hunting practices of ancient hunter-gatherers one day, brain development in children and adolescents the next day, and the lives of marmoset monkeys the day after that!

Such a wide range of different topics means that biological anthropologists are rarely confined to one specific area of research. Instead, they use their knowledge of a broad range of subjects, combined with problem-solving skills and collaboration with other scientists, to make new discoveries. In addition, biological anthropology is one of the best-suited fields for working with people from all around the world, representing a hugely diverse range of cultures.

WHAT CHALLENGES FACE THE NEXT GENERATION OF BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGISTS?

The huge diversity of biological anthropology also means that researchers from many different fields, who will not be hugely knowledgeable about each other’s main area of research, will often need to work closely together. Because of this, it can be very challenging to coordinate experiments to gain the best possible results.

It is essential for anyone who hopes to become a biological anthropologist to be highly open-minded to unfamiliar differences between cultures; willing to learn from researchers who are more specialised than them in certain areas; and able to thrive when working as part of a larger, often international team. Emily also says that, so far, most biological anthropologists have worked exclusively with other scientists, but because history and culture are such important aspects of anthropology, there is now a growing demand for them to collaborate with researchers in the arts and humanities. It could be up to future generations of researchers to find new ways to extend the reach of biological anthropology beyond the scientific community.

HOW TO BECOME A BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGIST

• UCL Anthropology runs events, activities, and summer schools for students through the AnthroSchools programme.

• Find out more about a career in biological anthropology through the UCL Anthropology website.

• In Japan, the Human Behavior & Evolution Society of Japan and Anthropological Society of Nippon provide lots of useful information.

Although biological anthropology is a diverse field, Emily says that its foundations are based in biology, so that is the most useful subject for students to take at school. At university, some anthropology degrees offer biological anthropology as an option. You could also take broad-based science degrees like human sciences or arts and sciences.

Emily also says that it is important to understand human society, which subjects like geography, sociology and psychology are useful for. Since biological anthropologists often carry out their research all over the world, it might also be beneficial to study extra languages in school.

HOW DID EMILY BECOME A BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGIST?

I loved art and being creative throughout my childhood and adolescence, but I also loved finding out how the world works. I never thought I would become a biological anthropologist – but it makes sense, as in my job I need to combine science with creative thinking.

I never thought I would become a scientist! I just kept doing what I loved, and one day I’d become a lecturer and researcher at a university. I’m very lucky to have been able to pursue my interests as my job.

Investing in collaborations and working well with people have made me much more productive. Supporting and being supported by your team means you all work much better.

It’s important not to take things too personally when things go wrong. It helps me to talk things through with people, and have a good break. It also helps to take my dogs for a walk!

It’s hard to pick a single proudest moment, as my achievements have been a series of small steps, supported by other people, that have all built up to now. One thing I am very proud of is the course I designed and teach at UCL Anthropology, called Biosocial Approaches to Childrearing. It’s based on my research to understand the different ways in which people look after children and adolescents across cultures, and how that impacts development.

EMILY’S TOP TIPS

01 Find your interest. To be a researcher, you need to keep learning new things all the time – so make sure you enjoy what you are learning.

02 Don’t worry about failing or making mistakes. The important thing is to think is about what you could do better next time, so you can improve.

03 Things often go wrong in research, and that’s very normal – but the important thing is to reflect on the issues, so you keep making improvements.

HOW DID MASAHITO BECOME AN EVOLUTIONARY ANTHROPOLOGIST?

In my first biology class in my high school (I was 15 years old), the teacher introduced a book entitled The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins. I was really impressed with the simple idea that a variety of animal behaviours can be understood in terms of survival and reproduction. This excitement made me interested in biology and has remained in my mind since that day.

Completing several processes in research (making a research plan, collecting data, analysing the data, discussing the results, writing and revising a paper, and publishing the final outcome) is sometimes really tough, but also lots of fun. Like the adolescent sociality project, conducting research with many colleagues and collaborators is exciting.

I have explored human behaviour from an evolutionary perspective for more than ten years. What most left an impression was my first research as an undergraduate, where I observed people at a train station. I couldn’t collect data at all in the beginning, but I gradually got used to it, and then I thought that I could understand ‘a piece of nature’ of the people and the place.

In studies of (non-human) animal behaviour, researchers often perform field observations in natural settings. In humans, however, such an approach is difficult due to several theoretical and experimental reasons, including ethical problems. So, we aimed to better understand the daily lives and thoughts of teenagers through their photographs.

Many early career researchers have experienced difficult situations, but fortunately I can continue to conduct research activities thanks to many people. I am proud of it. I have recently begun a few new projects, so I hope to enjoy them in the short-medium term.

Cherish and explore the exciting things that you face in your life, now and in the future. They will enrich your life!

Do you have a question for Emily or Masahito?

Write it in the comments box below and Emily or Masahito will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)