What if we could step in the shoes of migrants and inhabitants on the island of Lampedusa?

The Italian island of Lampedusa has become a major transit point for migrants seeking to enter Europe. With thousands arriving, and many dying on route, migration is portrayed as a humanitarian and political crisis. Dr Alessandro Corso, based at the University of Oxford in the UK, is working towards creating a platform for migrants and locals on Lampedusa to share their experiences. The hope is to dismantle the language of fear and create a more positive view of migration

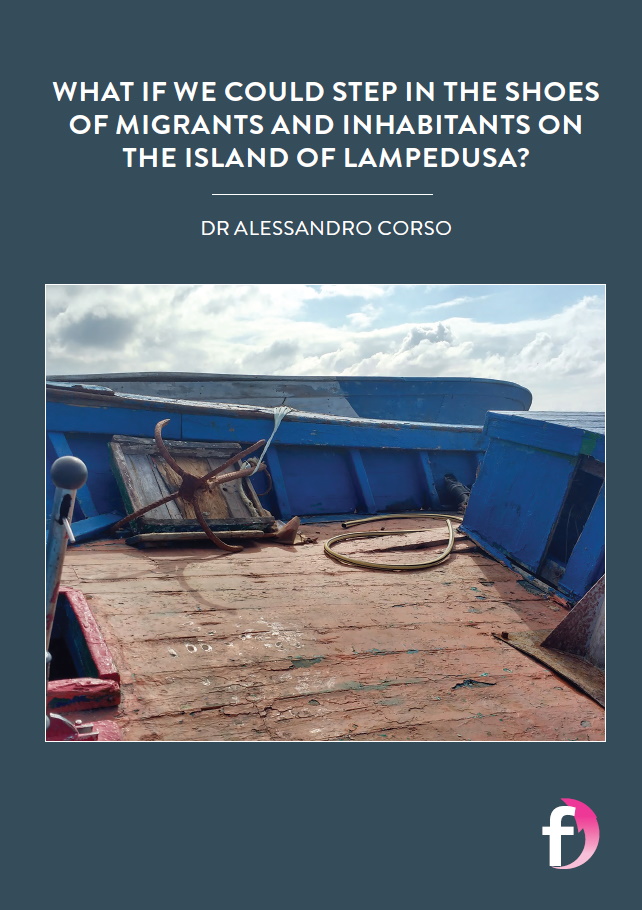

‘It is night-time in Lampedusa when the coast guard boat approaches land, and the dazed faces of the migrants appear more distinctly from the darkness. As the boat moves closer to the pier, the beams from the spotlights on land illuminate them. “They have been at sea for two days,” the coast guard captain tells me. The first migrants to touch land almost fall to the ground. They are weak after so many hours at sea… As they land, the migrants, mostly male, are pushed quite roughly towards the medical check-up area. Their feet are mostly swollen. Some are wearing t-shirts, while others are naked from the waist up.’ (Excerpt from a book manuscript by Alessandro Corso.)

Imagine an island in the Mediterranean Sea, bathed in sunshine and surrounded by crystal clear, blue waters and white, sandy beaches. Now imagine shoes, clothing, books and dead bodies retrieved by local fishermen in their fishing nets, or washing up on to the island’s shores. How would you feel if you lived on this island? What would you be thinking if you arrived at these shores, as a migrant, having escaped from terrifying ordeals in your home country and travelled for days over treacherous waters to get here? How would you be received by those who live on this island, the migrant officials who are paid to police it, and doctors or cultural mediators who are there to offer medical, legal and psychological support?

Lampedusa is an Italian island located to the north of Libya, east of Tunisia and at the southernmost border of Europe. Since the 1990s, it has become a militarised frontier for irregular migration.

Dr Alessandro Corso is starting a project that seeks to provide a safe space for migrants and the inhabitants of Lampedusa to share their experiences, both within the community of Lampedusa and with the rest of the world. Based at the University of Oxford, Alessandro is an anthropologist who wants to dismantle superficial representations of forced migration and build a more engaged and less simplistic narrative – one that is based on lived experiences.

For various reasons, politicians and media outlets in the UK, Europe and the US (as well as other regions around the world), represent migrants as a potential threat. Migration is seen as an ongoing crisis, and borders as sites of inevitable tragedies. This standpoint propagates a language of fear that has grown louder in recent times. We are often confronted with oversimplified and misleading representations of threatening or needy migrants, heroic rescuers, and angry and frustrated local communities. Rather than unite people, these representations divide people and reinforce ideas of ‘us’ and ‘them’.

“At the borderland of Lampedusa, where migrants land after being rescued at sea by NGOs, fishing vessels or naval ships, the imagined ‘us’ and ‘them’ meet,” says Alessandro. “Doctors, fishermen, border agents, police officers and migrants share their stories and experiences. Such encounters allow for personal stories to be expressed in such a way that ‘fear’ often turns into ‘mutuality’ and ‘distance’ becomes ‘proximity’.

ENGAGING WITH MIGRATION WORKERS, ARTISTS AND TEACHERS

One of the key aspects of Alessandro’s project will be to use workshops, seminars and public events to facilitate an in-depth reflection about how the media and politicians portray the border zone. “The idea behind this project is to allow the inhabitants of Lampedusa to find a communal space where they feel comfortable to freely express themselves. The island is small (about five thousand inhabitants) and it is often difficult to create spaces of aggregation,” says Alessandro. “Different groups of people from separate dimensions (local residents, migration workers, migrants, visitors, researchers) would usually occupy different spaces meaning their views are not shared productively. I believe that by creating a shared space for open discussion and collaboration, these disparate groups will be able to find unexpected elements of communion.”

From previous fieldwork in 2016 and 2017, Alessandro predicts that in light of the widespread sense of neglect and abandonment by the Italian state, the EU, and the law more broadly, there will be a profound need to express personal and shared stories of suffering, abandonment and frustration, but also of hope and love.

A MUSEUM OF SHARED EXPERIENCES

Tragically, the island of Lampedusa has received the dead bodies of migrants since the 1990s. They were first caught by fisherman in their fishing nets, but are now mainly retrieved by the Navy or coastguard. Such experiences have had a significant impact on individuals and there are stories of fishermen not eating properly for a long time or refusing to go back to sea. However, some local residents have been actively investing their time and energy in collecting migrants’ belongings that have washed ashore, such as shoes, clothing and books. As a result, a museum named Porto M (Harbour M) has been created, offering different perspectives on migration.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM155

‘“They have been at sea for two days,” the coast guard captain tells me. The first migrants to touch land almost fall to the ground.” (Excerpt from a book manuscript by Alessandro Corso.)

Porto M, a museum of shared experiences

Imagine an island in the Mediterranean Sea, bathed in sunshine and surrounded by crystal clear, blue waters and white, sandy beaches. Now imagine shoes, clothing, books and dead bodies retrieved by local fishermen in their fishing nets, or washing up on to the island’s shores. How would you feel if you lived on this island? What would you be thinking if you arrived at these shores, as a migrant, having escaped from terrifying ordeals in your home country and travelled for days over treacherous waters to get here? How would you be received by those who live on this island, the migrant officials who are paid to police it, and doctors or cultural mediators who are there to offer medical, legal and psychological support?

Lampedusa is an Italian island located to the north of Libya, east of Tunisia and at the southernmost border of Europe. Since the 1990s, it has become a militarised frontier for irregular migration.

Dr Alessandro Corso is starting a project that seeks to provide a safe space for migrants and the inhabitants of Lampedusa to share their experiences, both within the community of Lampedusa and with the rest of the world. Based at the University of Oxford, Alessandro is an anthropologist who wants to dismantle superficial representations of forced migration and build a more engaged and less simplistic narrative – one that is based on lived experiences.

For various reasons, politicians and media outlets in the UK, Europe and the US (as well as other regions around the world), represent migrants as a potential threat. Migration is seen as an ongoing crisis, and borders as sites of inevitable tragedies. This standpoint propagates a language of fear that has grown louder in recent times. We are often confronted with oversimplified and misleading representations of threatening or needy migrants, heroic rescuers, and angry and frustrated local communities. Rather than unite people, these representations divide people and reinforce ideas of ‘us’ and ‘them’.

“At the borderland of Lampedusa, where migrants land after being rescued at sea by NGOs, fishing vessels or naval ships, the imagined ‘us’ and ‘them’ meet,” says Alessandro. “Doctors, fishermen, border agents, police officers and migrants share their stories and experiences. Such encounters allow for personal stories to be expressed in such a way that ‘fear’ often turns into ‘mutuality’ and ‘distance’ becomes ‘proximity’.

ENGAGING WITH MIGRATION WORKERS, ARTISTS AND TEACHERS

One of the key aspects of Alessandro’s project will be to use workshops, seminars and public events to facilitate an in-depth reflection about how the media and politicians portray the border zone. “The idea behind this project is to allow the inhabitants of Lampedusa to find a communal space where they feel comfortable to freely express themselves. The island is small (about five thousand inhabitants) and it is often difficult to create spaces of aggregation,” says Alessandro. “Different groups of people from separate dimensions (local residents, migration workers, migrants, visitors, researchers) would usually occupy different spaces meaning their views are not shared productively. I believe that by creating a shared space for open discussion and collaboration, these disparate groups will be able to find unexpected elements of communion.”

From previous fieldwork in 2016 and 2017, Alessandro predicts that in light of the widespread sense of neglect and abandonment by the Italian state, the EU, and the law more broadly, there will be a profound need to express personal and shared stories of suffering, abandonment and frustration, but also of hope and love.

A MUSEUM OF SHARED EXPERIENCES

Tragically, the island of Lampedusa has received the dead bodies of migrants since the 1990s. They were first caught by fisherman in their fishing nets, but are now mainly retrieved by the Navy or coastguard. Such experiences have had a significant impact on individuals and there are stories of fishermen not eating properly for a long time or refusing to go back to sea. However, some local residents have been actively investing their time and energy in collecting migrants’ belongings that have washed ashore, such as shoes, clothing and books. As a result, a museum named Porto M (Harbour M) has been created, offering different perspectives on migration.

“As you enter Porto M and you look up, old shoes once belonging to travelling migrants hang from the roof,” describes Alessandro. “They have been retrieved by the shores of Lampedusa or found at the boat cemetery. This is a remote space now surveilled by the Italian Air Force, where dozens of giant boats have been left in abandonment. Inside these boats, you can still find the belongings of migrants: backpacks, milk boxes, clothes and toothbrushes.”

Importantly, Porto M is not simply a museum of objects. There are performative arts, traditional Sicilian puppet playing and storytelling, music exhibitions, poetry and theatre, all of which tell the stories of colonisation, incarceration, forced migration, abandonment and mutual suffering in new and creative ways.

Alessandro’s aim for his ESRC project is to bridge the gap between academia and art. In a similar way to the Porto M project, he hopes to engage with locals’ creative responses, interpretations and representations of the hardships of irregular migration, and the complexities of life at the borderlands of Europe in these present times.

ALESSANDRO’S HOPES

“The project is an opportunity for the people who live on Lampedusa to share their difficulties, worries, needs and perplexities,” explains Alessandro. “I want to try and channel their energies into a productive exercise of speech against ongoing superficial and false representations of the reality they have to live with on a daily basis, albeit from very different perspectives, and with greatly diverse consequences.”

Through art, music and theatre, some of us may be able to see beyond the stereotypes perpetuated by politicians and media outlets, and recognise the challenges that irregular migrants around the world face. This recognition will help us understand that so-called ‘people on the move’ (irregular migrants or refugees) are forced into situations that put their well-being and lives at risk. As Alessandro says, “We should be mindful that a real threat for any community comes from superficial representations of ‘otherness’ (i.e. ‘us’ and ‘them’) that go against people’s lived experiences.”

DR ALESSANDRO CORSO

DR ALESSANDRO CORSO

Oxford Department of International Development

University of Oxford, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Anthropology

RESEARCH PROJECT: Alessandro is creating a safe space for migrants and locals on the island of Lampedusa to express themselves through art, music and theatre. The ultimate aim is to channel people’s energies towards a more productive and positive view of migration that dismantles superficial and false representations of the realities they face.

FUNDER: Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC)

DR ALESSANDRO CORSO

DR ALESSANDRO CORSO

Oxford Department of International Development

University of Oxford, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Anthropology

RESEARCH PROJECT: Alessandro is creating a safe space for migrants and locals on the island of Lampedusa to express themselves through art, music and theatre. The ultimate aim is to channel people’s energies towards a more productive and positive view of migration that dismantles superficial and false representations of the realities they face.

FUNDER: Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC)

ABOUT ETHNOGRAPHY AND ANTHROPOLOGY

Put simply, anthropology is the study of humanity, while ethnography is the writing of the human condition through fieldwork: an ‘immersion’ in individual cultures. Alessandro’s research could be defined as a study of sorts, but the people he works with and writes about are the substance and force behind his writing, thinking and analysis. He is not merely studying migrants, nor the Lampedusa inhabitants, but rather attempting to share time and meaningful moments with them as they go about their daily lives. In turn, they have become inspirational voices, companions and friends that represent the realities his work is trying to explain.

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO BUILD A MORE POSITIVE NARRATIVE OF MIGRATION?

The introduction to this article was an excerpt from Alessandro’s book manuscript, which is based on his research. This abridged preface from the same manuscript offers a heart-felt explanation as to why it is important to build a more positive narrative around migration:

“We could pretend to be blind to our own experience, and deaf to our own ears. But can we afford to keep living with indifference? Can we leave reality unquestioned and take it for granted when it seems to concern someone else, or something other than our world, and merely accept it, as if it does not belong to us, whatsoever? Are the margins of our safe zone as tragic and dangerous as we are told by the media? Are borders as morally unstable as the images broadcasted on TV and social media seem to suggest? The world map signals Lampedusa as a dot drawn between Sicily and Libya. The island reflects a micro-world within a macro-space of global migration, political issues, economic inequalities, illegality, state abandonment and profit. It is an ideal space to address these issues outside the geographical, ethical, academic and imaginative borders. It stands as a frontier of a political imagery which fails when compared with everyday experience. It is a symbol of a tragedy which keeps hidden voices of suffering and pain; a conglomerate of acceptance and abandonment, profit and suffering, indifference and love.”

You can access Alessandro’s research thesis, here: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13403/1/Lives_at_the_Border_Thesis_A_Corso.pdf?DDD5

WHY IS ILLUSTRATION ANOTHER POWERFUL MEANS OF SHARING ANTHROPOLOGICAL RESEARCH FINDINGS?

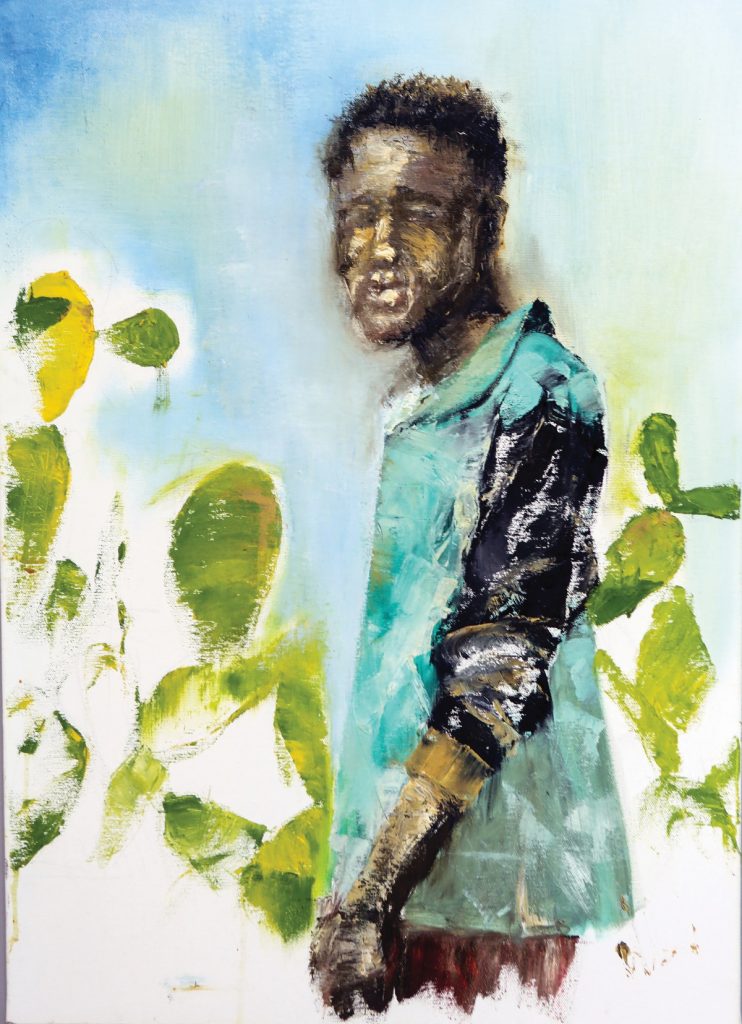

Ever since he was a young child, Alessandro has been drawing and painting, which has culminated in some of his artwork being featured in the Illustrating Anthropology exhibition. For him, illustration provides a unique means of studying the subjects at hand. “I believe that giving oneself the freedom to express what one is experiencing in the field (particularly when fieldwork concerns emotionally and ethically challenging contexts) allows researchers to investigate their research questions from a particularly interesting angle,” says Alessandro. “Self-reflection and introspection are fundamental to fieldwork in anthropology and the social sciences, as they are more generally in life. Art is a powerful way to explain the relationship between the world we learn about and ourselves.”

WOULD ALESSANDRO RECOMMEND A CAREER IN ANTHROPOLOGY?

It really depends on what it is that you are interested in and passionate about. Anthropology is a fascinating discipline which dismantles reality, questions certainty, raises doubt and encourages you to learn about yourself. “You might be fascinated by the idea of seeking to understand a particular way of life practised in a remote or nearby geographical areas. You might be interested in religious practices, fascinated by the symbolisms of language, or drawn towards a historical, political or existential interest in violence, pain, suffering, reciprocity or love,” says Alessandro. “Ultimately, anthropology revolves around the question of what it means to be human, but humanity may be approached from many perspectives and sub-questions.”

Limbo

“Theirs are the bodies of defeat, bodies of pity, bodies of suffering. They are bodies of need, bodies of silence, bodies veiled by the taboo of exploitation, torture, violation of human rights, by the inhumanity of humans. And these bodies are captured by photographic machines, videos and careful eyes that observe, quickly, from one detail to another…” (Fieldnotes 26/09/2016)

Credit: Alessandro Corso https://illustratinganthropology.com/alessandro-corso/

The Back Hole

“Behind the First Welcoming Center, nearby the dormitories, there was a hole through the high fences’ metal net that was left there and never repaired. According to most people I spoke to on the island, the hole allowed the detained migrants to get out of the First Welcoming Center and come back in, freely.

This was the official story, as Nino told me, to further add that no one cared much about whatever would have happened to the guests. Their physical, as well as mental conditions, did not concern police and military agents monitoring the island. If some migrants wandered around, ‘it was not their business’, repeated Nino, ‘because officially, these migrants escape from the back of the Centro (FWC).’ Theirs was an apparently free walk through Via Roma or by La Guitgia beach, constantly watched by the police force, but practically left and euphemistically abandoned to themselves.”

Credit: Alessandro Corso https://illustratinganthropology.com/alessandro-corso/

EXPLORE A CAREER IN ETHNOGRAPHY AND ANTHROPOLOGY

• Prospects provides a wealth of advice on what you can do with an anthropology degree, including the different jobs and routes for further study you might want to embark on: www.prospects.ac.uk/careers-advice/what-can-i-do-with-my-degree/anthropology

• UKRI has put together a useful career guide for anthropologists that may well prove useful to those interested in the field: esrc.ukri.org/files/public-engagement/social-science-forschools/careers/careers-in-anthropology-a-guide/

• The average salary range for an anthropologist is between £36,000 and £64,000, depending on experience.

PATHWAY FROM SCHOOL TO ANTHROPOLOGY

Alessandro recommends a broad range of subjects that you might consider if you want to get into the field of anthropology. These include literature, history, philosophy, art, biology and languages (both modern and ancient). https://www.prospects.ac.uk/careers-advice/what-can-i-do-with-my-degree/anthropology

HOW DID ALESSANDRO BECOME AN ANTHROPOLOGIST?

ARTWORK (ILLUSTRATION, THEATRE, STORYTELLING, WRITING) IS A LARGE FEATURE OF YOUR RESEARCH. DID YOU WANT TO BE AN ARTIST WHEN YOU WERE GROWING UP?

I believe that anthropology, as I understand it (and practise at this very early stage in my academic career), is inevitably linked with art. You may be an artist who works as an anthropologist, or an anthropologist who does art. You may be both. However, I generally believe that once you try to put a label on what you are, things seem to lose their mystery and meaning. Art is a mystery, and it could be argued that anthropology is a mystery, too. Certainly, humanity and life more broadly are the greatest mysteries we come to experience. As such, it shall be left for what it is, and we, as scholars, writers, intellectuals, artists, should perhaps only and ultimately aim to learn from it.

YOU STUDIED HUMAN SCIENCES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM. WHO OR WHAT INSPIRED YOU TO STUDY THIS SUBJECT?

It was by chance! A series of events (my mother’s vision, accidental encounters, luck and belief in myself) which led me from Milazzo (Sicily) to Durham in the UK to study a subject I knew nothing about.

WHAT DO YOU LOVE MOST ABOUT THE WORK YOU DO?

I love writing. This job gives you the opportunity not only to write, but to read, dedicate a large time of your life to learning from others, and most of all, it ‘forces’ you to be in the field. It requires you to experience part of what you are willing to write about. This ‘rigorous’ combination of practice and theory allowed me to experience an awareness of the world and myself that I may have never been able to acquire otherwise.

HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE YOURSELF AND ARE THESE CHARACTERISTICS USEFUL IN ANTHROPOLOGY?

It is hard to describe oneself – and can only ever be an approximation. I am disciplined and diligent, passionate and idealist, stubborn and determined. Some of these characteristics help and others do not. I always try to find some sort of balance, and it is towards that balancing exercise that we should perhaps aim in anthropology and, more generally, in life.

ALESSANDRO’S TOP TIPS

01 Read, write, watch movies, and engage with your surroundings, whatever these may be. Learn how to value what may appear to be obvious, unimportant or banal at first glance. This will help inform you and develop your knowledge, as well as encourage you to encounter different viewpoints that will aid you personally and professionally.

02 Be open: life may offer things you do not expect. Be ready to embrace them, but also accept when they do not take the direction you imagined or hoped for.

03 Follow what makes you feel alive and passionate – you should study hard but enjoy life as you do so. Being disciplined is important, but by exploring what fascinates you, it will be easier to work hard.

Do you have a question for Alessandro?

Write it in the comments box below and Alessandro will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

Mr. Corso, you say that your hope is to “dismantle the language of fear and create a more positive view of migration”. I am wondering how woulod you feel if you lived on an island with 6000 inhabitants and in 2 days 8000 migrants from Africa come and set fire to the encampment they were put in the first night they came to Lampedusa. There’s a wealth of videos on YouTube showing extremely hostile and aggressive behavior of Africans on lampedusa. Look at this a bit. Even better, go to Lampedusa and see it for yourself. As the Croatian saying goes, stop selling fog and start seeing situation for what it is. The solution to migration crisis is not in opening exhibits where you share your feelings. And don’t think this comes from a right winger. I am leftist through and through, but I also have eyes to see and brain to think with. The solution is not to hold hands and sing Kumbaya, but to do something concrete about helping immigrants in their country so that they don’t have to literally invade tiny islands in search of passage to EU. You are wasting resources on something even a blind person can see. What do you think Italians in Lampedusa will tell you when they don’t feel safe in their own home? It’s easy to sell fog when you’re sitting in Oxford and not living on Lampedusa.

Dear Drazen,

I have read your comments on my work for Futurum.

I will begin by saying that I am sorry to hear that tone of frustration. I understand where you are coming from. I was there when cameras and politicians were not “present” as they appear to be in the most recent events during very difficult situations for migrants, inhabitants, and workers.

I am aware that the specific article on Futurum does not (and cannot) address the complexity of the issue; in fact, that is not the point of that piece. It is instead a starting point to try to encourage teachers and students around the world to engage critically with a phenomenon that is treated with extreme superficiality and lack of knowledge of everyday experience. Art is a possible form of communicating a political, legal, economic, and socio-cultural reality that research has attempted to untangle for decades often unsuccessfully reaching the public at large.

My whole work since before PhD has been focusing on the island of Lampedusa. I lived there for 12 months in 2016-2017 and kept returning almost every year for shorter visits. I would encourage you to have a look at my profile and some of the academic work published in the past years if you are interested in understanding what my position is and how I tried to make sense of the phenomenon in the past eight years of my work. Here some links:

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/14634996221128104

https://blogs.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2021/07/something-better

https://brill.com/view/journals/puan/4/2/article-p208_004.xml?language=en

Feel free to contact me if anything is unclear or you need further clarifications.

Best wishes,

Dr. Alessandro Corso