Why do people stay?

Though migration is in the news almost daily, most people do not migrate, even if they have the opportunity and means to do so. Why not? At the University of Cambridge in the UK, Dr Daniel Robins has been researching immobility, and has discovered that it is often linked to feelings of duty and belonging

TALK LIKE A HUMAN GEOGRAPHER

IMMOBILITY – people staying in their country of birth, either by choice (voluntarily) or because they cannot leave (involuntarily)

GLOBAL CITIZEN – somebody who feels they are part of a worldwide human community

MIGRATION – the movement of people from one place to another in order to live there

PATRIOTISM – the feeling of love, devotion and attachment to one’s country

RESCALE – change the size or scale at which you are looking or thinking about something

In the year 2020, over 280 million people were living in a different country to the one they were born in. That is more than three international immigrants for every 100 people in the world. You, someone in your family, or one of your friends may well be one of them, and you may have already thought about why people choose to move to a different country. But, have you ever considered why people choose to stay?

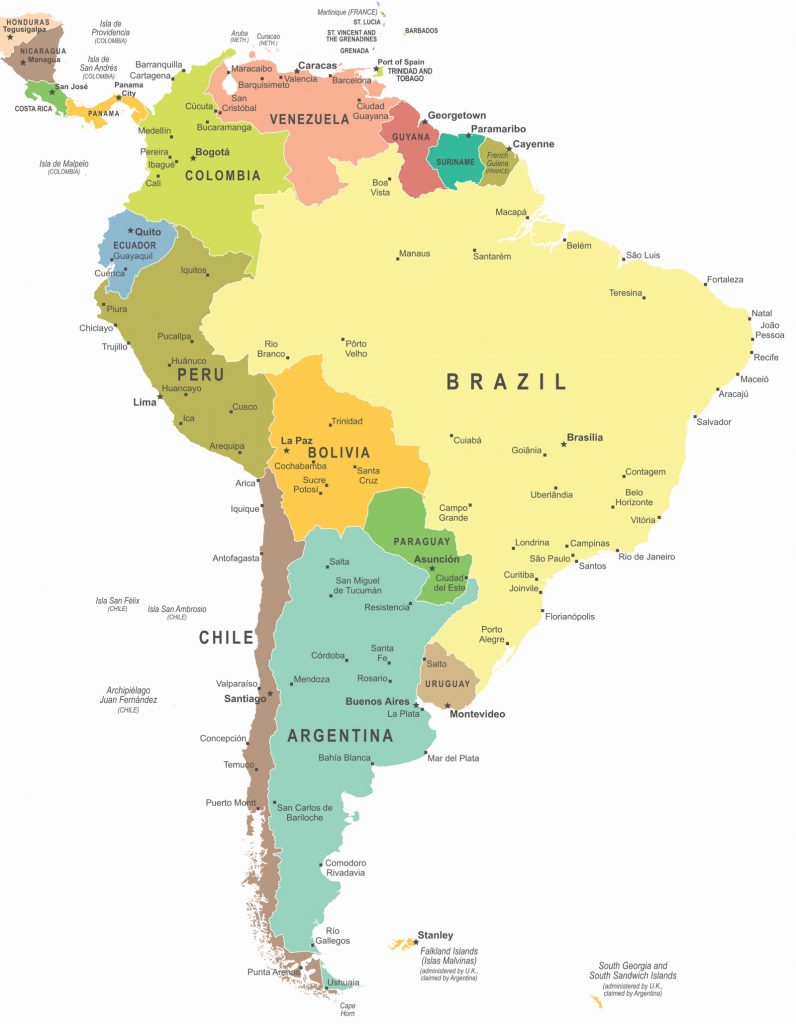

Immobility is the other side of the migration coin. That is, the 7.5 billion people who have stayed in their country of birth, despite the fact that many of them could choose to move if they wanted to. Dr Daniel Robins is a postdoctoral researcher in human geography at the University of Cambridge, and he has been asking what causes the majority of people not to migrate. Focusing his research on London, in the UK, and São Paulo, in Brazil, he hopes that investigating the reasons for immobility will eventually give us a deeper understanding of why other people leave.

HOW CAN WE INVESTIGATE IMMOBILITY?

Daniel’s work happens in four main stages: literature review, data collection, analysis and writing. During the first stage, he reads and makes notes on other people’s research to see what studies have been done before, and what conclusions they came to. By the time he has written up his notes into a literature review, he is fully up to date on the latest theories and concepts and knows what questions remain unanswered.

Following this, he spends his time talking to people about their lives and experiences. He collects information by recording his interviews and noting down his observations. The analysis stage involves transcribing the recordings to written text and searching the data for patterns. To make conclusions about immobility, he must find similarities in what lots of people say. Finally, Daniel writes about what he has learned from the interviews, linking it to the previous work he read about in the literature review stage. Daniel’s work is rigorous and meticulous – and reaps revealing results.

WHAT IS SNOWBALL SAMPLING?

Imagine a snowball rolling down a hill. As it rolls, it picks up more snow, and the bigger it gets, the faster it grows. In a similar fashion, Daniel finds people to interview by starting with a small group, then asking them for the names of other people he could contact. Because each person leads to several more, he can quickly accumulate a large enough sample of interviews.

Using the snowball sampling approach, Daniel conducted interviews in 2018 with Brazilian people who had chosen not to migrate. He chose to use a technique called semi-structured interviews. This means he had a number of set questions that he asked every participant, but also allowed room for follow up questions and time for the person to talk freely.

WHY DO PEOPLE CHOOSE TO STAY IN THEIR OWN COUNTRY?

Some people stay because of involuntary immobility. This means that they do not have the resources to migrate, even if they wanted to. Often, this applies to the poorest people in a society, who have no choice but to stay where they are. On the other hand, rich people are able to leave and enter the country whenever they like. They also have the resources to shield themselves from economic and social problems. This means that they have no reason to migrate permanently, unless there is a very serious reason such as war or natural disaster. These people are an example of voluntary immobility, where people have the capacity to leave but choose to stay.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM218

IMMOBILITY – people staying in their country of birth, either by choice (voluntarily) or because they cannot leave (involuntarily)

GLOBAL CITIZEN – somebody who feels they are part of a worldwide human community

MIGRATION – the movement of people from one place to another in order to live there

PATRIOTISM – the feeling of love, devotion and attachment to one’s country

RESCALE – change the size or scale at which you are looking or thinking about something

In the year 2020, over 280 million people were living in a different country to the one they were born in. That is more than three international immigrants for every 100 people in the world. You, someone in your family, or one of your friends may well be one of them, and you may have already thought about why people choose to move to a different country. But, have you ever considered why people choose to stay?

Immobility is the other side of the migration coin. That is, the 7.5 billion people who have stayed in their country of birth, despite the fact that many of them could choose to move if they wanted to. Dr Daniel Robins is a postdoctoral researcher in human geography at the University of Cambridge, and he has been asking what causes the majority of people not to migrate. Focusing his research on London, in the UK, and São Paulo, in Brazil, he hopes that investigating the reasons for immobility will eventually give us a deeper understanding of why other people leave.

HOW CAN WE INVESTIGATE IMMOBILITY?

Daniel’s work happens in four main stages: literature review, data collection, analysis and writing. During the first stage, he reads and makes notes on other people’s research to see what studies have been done before, and what conclusions they came to. By the time he has written up his notes into a literature review, he is fully up to date on the latest theories and concepts and knows what questions remain unanswered.

Following this, he spends his time talking to people about their lives and experiences. He collects information by recording his interviews and noting down his observations. The analysis stage involves transcribing the recordings to written text and searching the data for patterns. To make conclusions about immobility, he must find similarities in what lots of people say. Finally, Daniel writes about what he has learned from the interviews, linking it to the previous work he read about in the literature review stage. Daniel’s work is rigorous and meticulous – and reaps revealing results.

WHAT IS SNOWBALL SAMPLING?

Imagine a snowball rolling down a hill. As it rolls, it picks up more snow, and the bigger it gets, the faster it grows. In a similar fashion, Daniel finds people to interview by starting with a small group, then asking them for the names of other people he could contact. Because each person leads to several more, he can quickly accumulate a large enough sample of interviews.

Using the snowball sampling approach, Daniel conducted interviews in 2018 with Brazilian people who had chosen not to migrate. He chose to use a technique called semi-structured interviews. This means he had a number of set questions that he asked every participant, but also allowed room for follow up questions and time for the person to talk freely.

WHY DO PEOPLE CHOOSE TO STAY IN THEIR OWN COUNTRY?

Some people stay because of involuntary immobility. This means that they do not have the resources to migrate, even if they wanted to. Often, this applies to the poorest people in a society, who have no choice but to stay where they are. On the other hand, rich people are able to leave and enter the country whenever they like. They also have the resources to shield themselves from economic and social problems. This means that they have no reason to migrate permanently, unless there is a very serious reason such as war or natural disaster. These people are an example of voluntary immobility, where people have the capacity to leave but choose to stay.

Daniel is especially interested in two other reasons for voluntary immobility. The first of these is our sense of belonging. Where do you feel comfortable, safe and accepted? If the answer is where you live currently, you are unlikely to want to move. The second reason is that many of us feel a sense of duty to stay. Typically, our sense of duty is directed towards our family. If we feel that our family needs us, we will likely stay for their sake, even if we want to leave. People can also feel a sense of duty towards larger things such as their country or wider community. Interestingly, this can happen even if they do not agree with political or traditional ideas of patriotism. Showing loyalty to your country can mean very different things to different people.

THE SCALE OF BELONGING

Where do you feel you belong? You might be thinking of your household, school, town, country, or a mixture of these things. From a single family to a country of millions, our sense of belonging exists at many different scales.

When something happens at a national level that people do not like, their sense of belonging can be rescaled. This might mean looking to smaller scales; instead of feeling attached to their country, people might feel they belong to their city or neighbourhood. However, people can also rescale their belonging to something bigger; they might feel that they are global citizens more than they are citizens of a particular country. By rescaling, people can still feel they belong, even when they do not feel comfortable with political, economic or social changes at the local, national or international level.

HOW CAN MIGRATION RESEARCH INFLUENCE POLICY?

As well as investigating immobility, Daniel has been studying people who have migrated from Brazil to London. While writing his PhD, he found that many Brazilian migrants to the UK could live here by claiming ancestral European Union passports from countries like Italy and Portugal. However, there are also many who arrive on tourist visas and must work without the proper work visa. Due to Brexit, both groups are now facing similar problems.

Daniel hopes that his research will persuade the UK government to add Brazil to the Youth Mobility Scheme. This scheme works similarly to an exchange programme, with young people from either country having the opportunity to go and work for a couple of years in the other country. Daniel explains, “After Brexit, the UK government suggested that it might include more countries in the Youth Mobility Scheme to replace the freedom of movement lost due to Brexit. I think Brazil would be a good candidate, so I am using my research to try to convince the government of this.”

Daniel’s research reminds us that the world around us – and how and where people choose to live their lives – is changing all the time. Studies into human geography will always result in fascinating insights and can even shape how some of those changes come about.

DR DANIEL ROBINS

Postdoctoral Researcher

University of Cambridge, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH

Human Geography

RESEARCH PROJECT

Understanding immobility and migration in Brazil and the UK

FUNDER

Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC)

This research was funded by the ESRC Postdoctoral Fellowship scheme. Grant number: ES/V011863/1

Postdoctoral Researcher

University of Cambridge, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH

Human Geography

RESEARCH PROJECT

Understanding immobility and migration in Brazil and the UK

FUNDER

Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC)

This research was funded by the ESRC Postdoctoral Fellowship scheme. Grant number: ES/V011863/1

ABOUT HUMAN GEOGRAPHY

Where do people live, how do they organise themselves, and how do they interact with their environment? Human geographers tackle these questions by examining how culture, communities, economics, history and politics interact. Where physical geography focuses on environmental processes and the natural world, human geography looks at how human lives, activities, values and social behaviour are shaped by the world around them.

WHAT ARE THE REWARDS AND CHALLENGES OF BEING A HUMAN GEOGRAPHER?

Daniel highlights that if you work as a researcher, one reward is that you get the chance to learn and write about topics that you find interesting. This freedom is rare in other types of jobs. On the other hand, you have to obtain your own funding, and this can be a challenging part of the job, sometimes harder than the research itself! This is because there is a lot of competition for a limited amount of research funding. Daniel points out that you need to show to the institutions that award funding that your research is going to be important and impactful.

WHAT ISSUES COULD THE NEXT GENERATION OF HUMAN GEOGRAPHERS EXPLORE?

Human geography is all about scale and places, and technology is rapidly changing how we see these things. Future human geographers will explore how faster communications and online services are allowing people to change the way they live and work. Traditionally, most people travel (often long distances) into city centres for work because jobs are centralised there in a physical space. Now, the internet makes it possible for many people to work from home, cutting out commuting time, and the COVID-19 pandemic has increased our awareness of that.

Daniel believes that the ability to decentralise workplaces will have big implications for how cities are structured and where people choose to live. Right now, many people want to live as close to the city centre as possible: throughout Europe, the countryside is being abandoned by young people who move to work in the cities. However, if a lot of jobs are moved online, will more people choose to live in smaller towns and villages? What impact will this have on how we build and develop cities? As a human geographer, these are just some of the questions you could be exploring.

EXPLORE A CAREER IN GEOGRAPHY

• The Geographical Association has advice on work experience, volunteering and career prospects.

• The Royal Geographical Society has lots of information on why you might choose to study geography.

• Watch this TEDx talk, ‘The Power of Geography to Make a Sustainable Future’ by Lisa Benton-Short.

• Geography is very diverse and people in this field come from a wide variety of backgrounds. For example, Daniel has worked with people with degrees in biology, computer science, philosophy, history, geology and anthropology, as well as geography.

• If you decide to study human geography at university, you may need to study English and at least one humanities subject in preparation – geography, politics, history, philosophy and economics are all good options.

• Daniel adds, “There are also aspects of human geography that are more scientific. For example, demography, which is the study and measurement of human populations. In cases like this, subjects like maths and IT would be useful.”

• Many geography courses allow you to study both human and physical geography. If you are interested in the physical side, mathematics, biology and physics will provide you with a good foundation. Check the requirements of university courses you might be interested in when you choose your subjects.

HOW DID DANIEL BECOME A HUMAN GEOGRAPHER?

WHAT WERE YOUR INTERESTS WHEN YOU WERE GROWING UP?

I was actually more interested in music when I was growing up. But I was always interested in the reasons why people act the way they do, and how ideas and beliefs about the world affect human behaviour.

WHO OR WHAT INSPIRED YOU TO STUDY PHILOSOPHY?

I wanted to study philosophy because I was interested in the nature of reality, people’s beliefs about reality, and how these beliefs affect our experience of the world. These are some of the fascinating questions that philosophy explores.

HOW DID YOUR DEGREE IN PHILOSOPHY LEAD YOU TO GEOGRAPHY?

Social sciences, including geography, are actually very influenced by philosophy. Philosophers will create theories to explain human behaviour, while social scientists will then often try to apply these theories in the way they conduct their research and interpret what they find. So, the two subjects are quite connected, even if it might not seem like it.

WHAT ARE YOUR PROUDEST CAREER ACHIEVEMENTS SO FAR? WHAT ARE YOUR AMBITIONS FOR THE FUTURE?

I was delighted to get the current position I have which has funded my research at Cambridge. My ambition is to get my next project about Venezuela funded so I can continue with my research. I am hoping to do a project which will be about migration in a very different context. At the moment, there is a very serious economic crisis in Venezuela, resulting in five million people leaving the country. These five million people play a very important role for those who stay, because they send money home to support their families. The problem is, for various reasons, this can be hard to do. I want to study the different ways these migrants manage to send money home.

DANIEL’S TOP TIPS

01 Because geography is such a diverse subject, don’t feel you should be limited to certain A-levels if you want to do a geography degree at university.

02 It is never too late to start a career in geography. I spent many years working in other sectors before deciding to pursue a university career.

03 It is important to be flexible in your interests and try to approach issues from different perspectives.

Write it in the comments box below and Daniel will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)