Combining scientific and traditional knowledge at Tse’k’wa

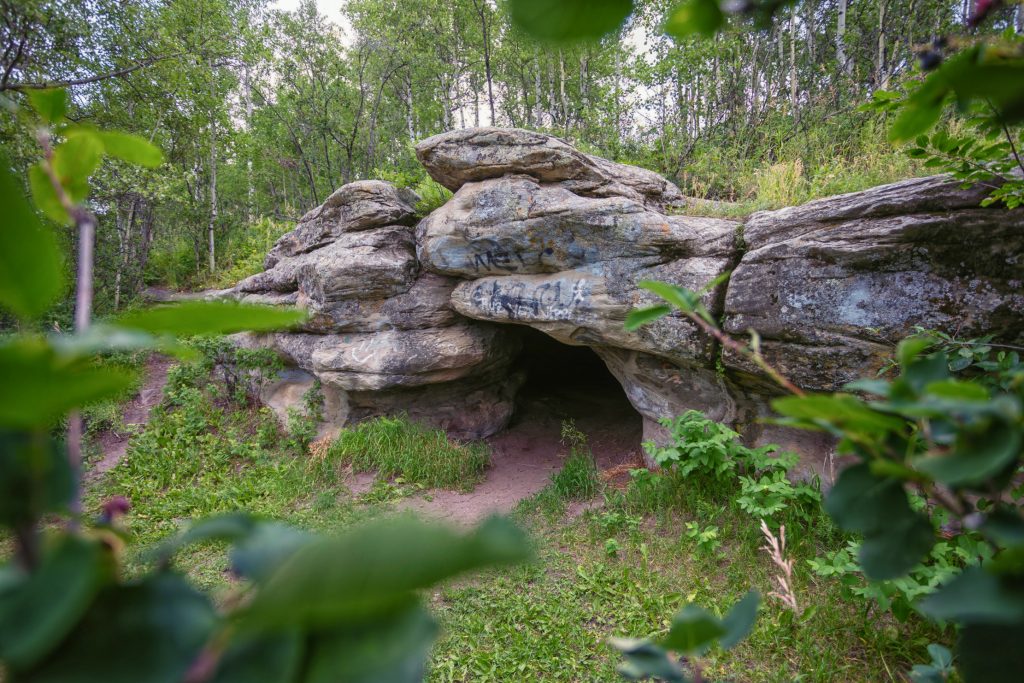

On a steep, rocky hillside in British Columbia, Canada, covered by tall trees and thick bushes, lies Tse’k’wa, an incredibly well-preserved archaeological site that tells the history of the Dane-zaa people whose ancestors have lived in the area for thousands of years. Dr Jon Driver, an archaeologist at Simon Fraser University, helped excavate the site in the 1980s and is now working alongside the Dane-zaa and Alyssa Currie, Executive Director of the Tse’k’wa Heritage Society, to preserve and celebrate Tse’k’wa for generations to come.

Talk like an archaeologist

Dane-zaa — a group of First Nations people from the Peace River area of British Columbia and Alberta in Canada, sometimes referred to as the Beaver People

First Nations — Indigenous peoples of Canada who are recognised as original inhabitants of the land

Indigenous — relating to the original people of a place

Repatriation — to return something to its original place

Tse’k’wa, which means ‘Rock House’ in the language of the Dane-zaa people, is a cave in British Columbia, and is one of the oldest archaeological sites in Canada. The soil layers at Tse’k’wa have preserved many ancient artefacts that archaeologists have used to learn about the history of the Dane-zaa. Remarkably, the site has preserved evidence of Dane-zaa ancestors on the land for over 12,000 years.

“The first major excavation took place in 1983,” says Dr Jon Driver, who was one of the archaeologists working on the site at the time. “Further excavations at the entrance to the cave occurred in 1990 and 1991 and provided a larger collection of artefacts and animal bones which were stored at Simon Fraser University.” Now, decades later, these artefacts have finally returned home to their rightful place at Tse’k’wa.

What was life like at Tse’k’wa?

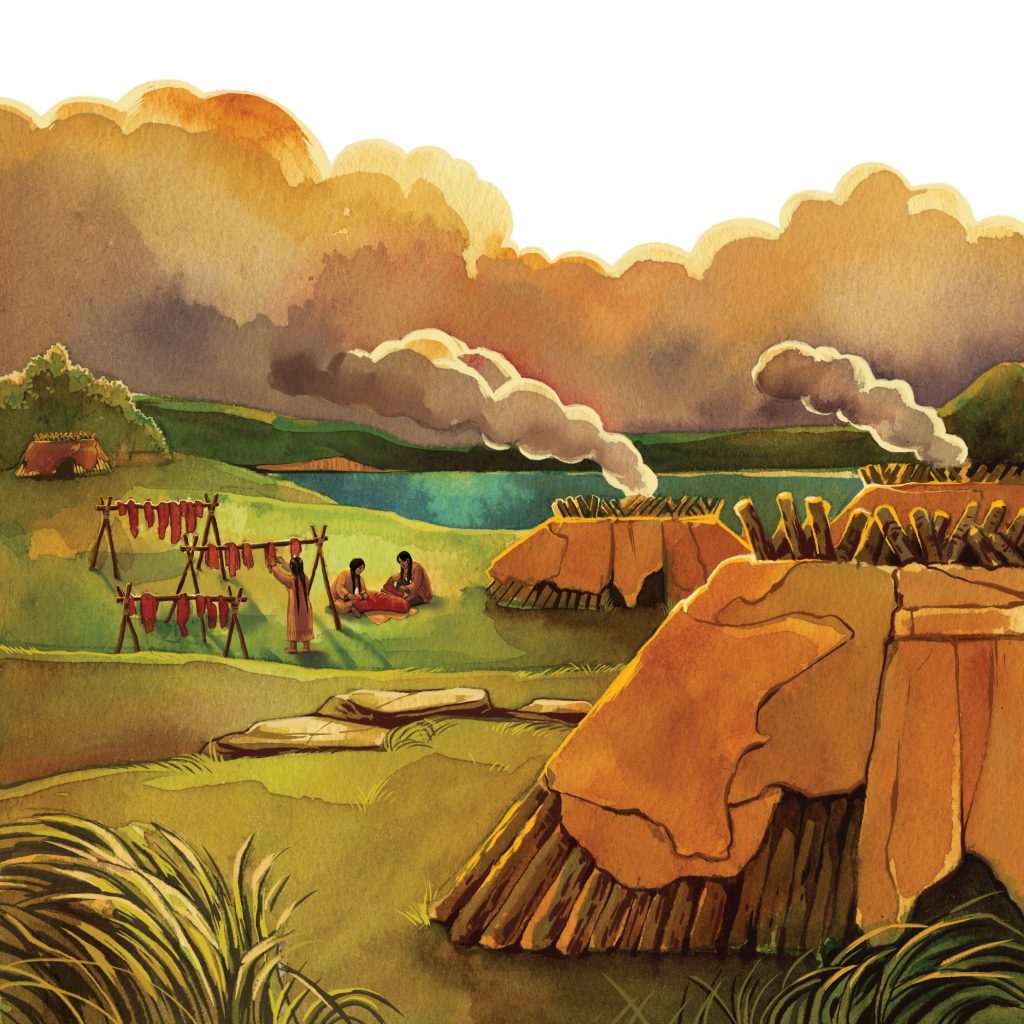

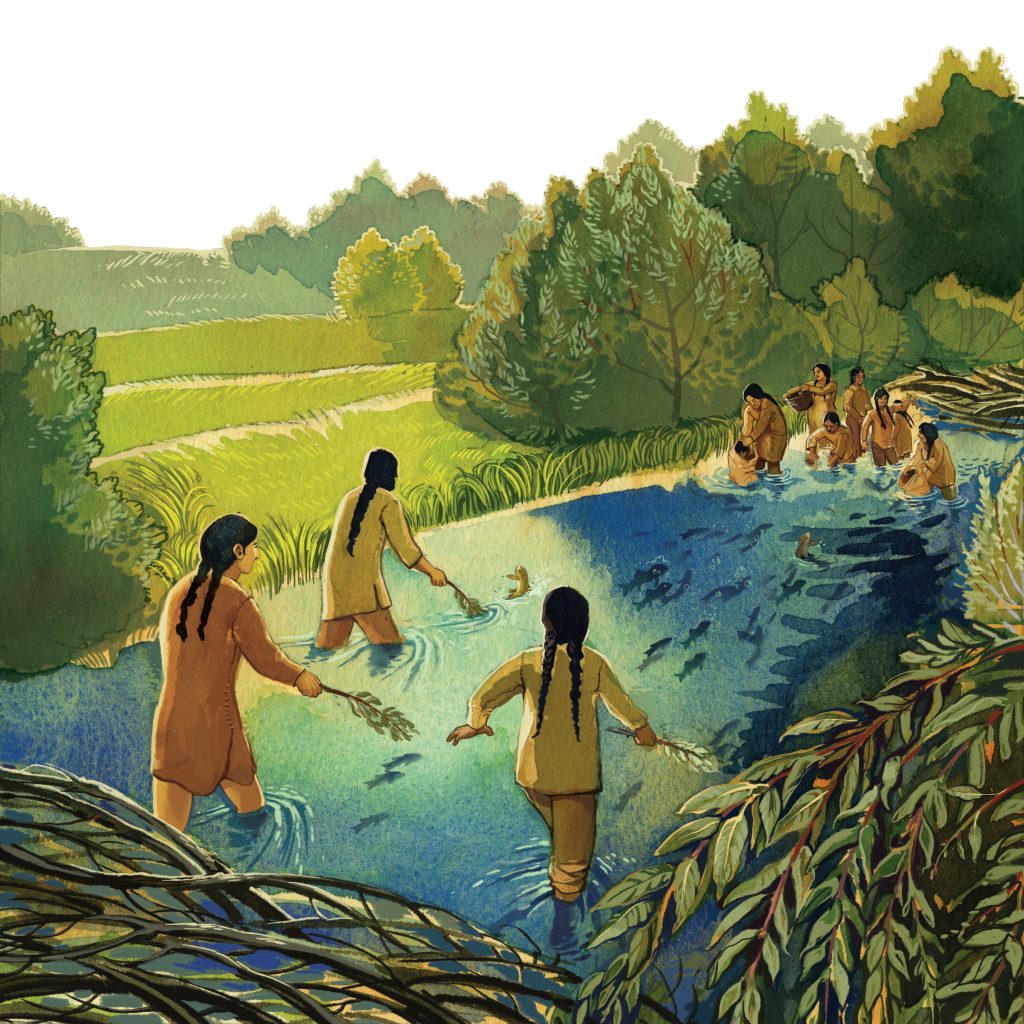

When Dane-zaa ancestors visited Tse’k’wa some 12,000 years ago, giant animals roamed the land, and people hunted, fished and gathered plants from the area to survive. During the excavations, archaeologists found bones from large animals and fish as well as two complete raven skeletons, which appear to have been ceremonially buried. “They also found a stone bead which shows a well-established appreciation of culture and beauty,” says Alyssa Currie, Executive Director of the Tse’k’wa Heritage Society, who works at the site.

Archaeologists also found some stone artefacts at the site which came from hundreds of miles away, proving that Dane-zaa ancestors would have traded and interacted with other groups. “We also have strong evidence that Dane-zaa ancestors trapped fur-bearing animals, providing them with more goods to trade and helping them survive in winters where temperatures could drop to –40°C,” says Jon.

As well as trading goods with other groups, the Dane-zaa have a long history of sharing stories between generations. “Dane-zaa ancestors shared stories and songs that have been passed down for 500 generations,” says Alyssa. “These stories tell us about a very different landscape compared to what is here today.”

For example, the Dane-zaa creation story tells us of the beginning of time, when there was only water. “The archaeological record at Tse’k’wa suggests that Dane-zaa ancestors arrived from the southeast, at a time when glaciers were melting and new land was emerging as the giant glacial lakes receded,” explains Jon. This is an example of how traditional and scientific knowledge can come together to enrich our understanding.

Combining traditional and scientific knowledge

“Elders and traditional knowledge holders can provide greater context for materials that archaeologists may not be able to identify based on science alone,” says Alyssa. “In turn, archaeologists can provide critical scientific information that may not be recorded in oral histories.”

For example, traditional Dane-zaa knowledge helped to explain why bones from fish known as ‘suckers’ were found at the site. While suckers are ignored by non-indigenous fishermen, they were an important food source for the Dane-zaa.

“On the other hand, the Dane-zaa talk about an ancient time when giant animals roamed the landscape,” says Jon. “At Tse’k’wa, we found remains of bison that are significantly bigger than modern bison, adding weight to the validity of the Dane-zaa’s oral history.”

Who looks after Tse’k’wa?

In 2012, three Dane-zaa First Nations, Doig River, Prophet River, and West Moberly, came together to purchase the Tse’k’wa site and create the Tse’k’wa Heritage Society (THS). “THS was formed in order to preserve the site and create a space to celebrate the Dane-zaa language, culture, history and spirituality,” says Alyssa. “This unique collaboration honours the history of Tse’k’wa as a gathering place and the unity of the Dane-zaa.”

Since 2012, THS has made many improvements to the site including an open-air amphitheatre for storytelling and drumming, healing gardens with traditional plants, and a trail leading to the cave with interpretive signs that feature information about the archaeological excavations alongside teachings from Dane-zaa elders. This fusion of traditional and scientific knowledge has been a cornerstone in the re-imagining of Tse’k’wa.

Celebrating Tse’k’wa

In 2024, after decades of advocacy by THS, all of the artefacts excavated from the site were repatriated from Simon Fraser University to Tse’k’wa. “Community gatherings have always been an important Dane-zaa cultural tradition, so, in July, we showcased Tse’k’wa’s new artefact repository space at a special repatriation event,” says Alyssa. “The event included prayers, dancing, traditional drumming and a shared meal.”

Having the artefacts back at Tse’k’wa is a huge achievement for the THS team. “I believe that the best protection for the site and the artefacts will come from people whose history is embodied in the site,” says Jon. “Archaeology is the study of the human past through material remains; who better to help explain these materials than the descendants of the people who created them?”

What’s next?

The team are hoping to create a world-class museum and education centre at Tse’k’wa that tells Dane-zaa stories alongside the ancient artefacts. “Now that the Tse’k’wa collection has been repatriated, THS will use this material for future cultural and educational programmes at the site,” says Alyssa. “THS has also partnered with Simon Fraser University to complete new, modern excavations of the site using both state-of-the-art archaeological methods and Indigenous cultural knowledge.”

Dr Jon Driver

Dr Jon Driver

Professor Emeritus, Simon Fraser University, Canada

Alyssa Currie

Executive Director, Tse’k’wa Heritage Society, British Columbia, Canada

Fields of research: Archaeology, cultural heritage, Indigenous studies

Research project: Repatriating archaeological artefacts to the Tse’k’wa Heritage Society

Funders: Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), First Peoples’ Cultural Council

About archaeology

“Scientific evidence suggests that every living person today is descended from a small group of Africans who lived hundreds of thousands of years ago,” says Jon. “Even though their descendants spread out over the world, we all retain certain human characteristics, such as language, art, caring for others, and the use of tools and fire. Archaeology reminds us that we share a common heritage and helps us fight xenophobia and racism. But at the same time, archaeology also reveals the diversity of human societies and lets us celebrate human ingenuity. Archaeology shows how people have adapted to an incredible range of natural environments, and that we are resilient and inventive in the face of change.”

What can archaeological artefacts teach us?

“Archaeological artefacts are an irreplaceable part of human history and culture; they can provide valuable insight into the past and inspire us to look to the future,” says Alyssa. “Because of Tse’k’wa, I have a much deeper understanding and appreciation of the place I live in and the people who have lived here since the last ice age. I think learning about the history and culture surrounding archaeological artefacts makes you a more empathic person.”

What skills and personality traits do archaeologists need?

“Archaeologists have to enjoy learning about many different fields of research and be happy working in teams,” says Jon. “We use many different methods, so we need to be able to communicate in plain language to explain how our research was conducted. I don’t know much physics, but I can explain how radiocarbon dating works. I’m not a biologist, nor a palaeontologist, but I can show someone how to tell the difference between a wolf bone and a deer bone. Archaeologists have to tell stories that are interesting and relevant to their audiences – but those stories have to be based on facts and repeatable research.”

“One of my university history professors taught me that the two most important tools of a historian are empathy and imagination,” says Alyssa. “I think this applies to anyone researching and educating people about culture, especially if it is not your own. A lot of academic research does not give you a complete picture of all cultures. In the case of Dane-zaa history and culture, most of my personal learning has been by listening to their elders and watching their knowledge holders.”

Pathway from school to archaeology

Jon suggests that geography is the most relevant subject to study at school, but also recommends studying history, science subjects and statistics. Many universities offer courses in archaeology, but you could also study anthropology, human evolution or human geography.

The Council for British Archaeology has videos describing ‘Pathways into Archaeology’ and blog posts from different people working in the field.

THS and the Department of Anthropology at the University of Northern British Columbia run an archaeology field school every two years at Tse’k’wa which allows students to explore the relationship between Indigenous and scientific ways of thinking.

Explore careers in archaeology

Getting some hands-on experience is a great way to find out if archaeology is the right career for you. Search online for volunteering opportunities or work experience. “In some countries, you can get involved with archaeological societies that offer the chance to do fieldwork,” says Jon.

Understanding cultural heritage is a crucial part of being an archaeologist, and can even be a career in its own right. “Attend and participate in your local cultural heritage events,” says Alyssa. “This can be as simple as attending talks at your local library or volunteering at your local museum.”

Meet Jon

Early in my life, I was fortunate to have teachers who encouraged me to question everything and to respectfully challenge other people’s views. Thanks to my father, I was always interested in being outdoors, and that was reflected at school in a focus on geography. I was also interested in how and why human societies operated, so I studied history and English literature. My original goal was to study anthropology or sociology at university, but I then discovered that archaeology allowed me to combine my enjoyment of the outdoors with the study of how human societies functioned.

When I was invited to work with the Tse’k’wa Heritage Society, I had very little experience of collaborating with Indigenous communities. Fortunately, I have colleagues whose example I could follow and who showed me how to build collaborations based on trust, honesty and being open to other points of view. Role models are not just for young people – you can be inspired by people throughout your life.

My favourite thing about Tse’k’wa has to be the rock formations. Carved by glacial meltwater, they change their form as the light changes, and it’s easy to see animal and human shapes emerging from the rock face. It was the unusual geology of the site that allowed the deep layers of soil and their record of people and animals to be preserved – so the history of people and animals preserved in the layers is mirrored by the people and animals that our imaginations let us see in the naturally sculpted rocks.

To unwind from work, I still try to spend as much time as I can outdoors, either hiking or gardening, but my wife and I get a great deal of enjoyment out of ballroom dancing. It may seem an unusual choice for a professor of archaeology, but it is a great combination of mental and physical exercise, and seems to be keeping us young!

Jon’s top tips

1. Don’t let other people tell you what to do with your life.

2. It’s OK to take some time off and explore before going to college or university. Be prepared for unexpected opportunities or new interests that may lead you in new directions.

Meet Alyssa

As a teenager, I enjoyed literature, crafts and spending time outdoors. My job at Tse’k’wa allows me to explore these interests in an Indigenous context: listening to traditional stories, learning beading and hidework, and visiting culturally significant locations across Dane-zaa territory.

I think my willingness to try new things has served me well in my career. Sometimes the best way to find out if you really enjoy doing something is to just do it. Volunteer. Try different summer jobs. Embrace new opportunities, especially if they stretch your comfort zone; that’s what makes you grow as a person.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM676

© Alyssa Currie

Jon Driver and Laura Webb at Tse’k’wa Archaeology Field School.

© Tse’k’wa Heritage Society

© Alyssa Currie

An archaeologist excavates an 11,000 year old bison bone.

© Jon Driver

The late Diane Bigfoot was an incredible mentor to me when I began my role at Tse’k’wa. Diane was a powerful advocate for Dane-zaa cultural revitalisation and represented Prophet River on the Tse’k’wa Board of Directors for over a decade. Diane was a strong believer in education and I try to honour her legacy in the work I do at Tse’k’wa.

Tse’k’wa is a place where all people are welcome to learn about Dane-zaa cultural heritage. It’s an incredible honour to learn about this place from the people whose ancestors have been visiting here for so many generations.

Alyssa’s top tips

1. It’s okay to change your mind; pursue opportunities that will open as many doors as possible and you’ll have lots of options. Many adults don’t want to admit it, but some of us are still figuring out what we want to be when we grow up.

2. My current job did not exist when I was a teenager. You never know what career opportunities will be available ten or twenty years from now.

Meet Alessandria

Alessandria Testani is a cultural heritage research analyst who wrote her thesis on the animal bones found at Tse’k’wa under Jon’s supervision.

The bones at Tse’k’wa tell a story of a strong boreal (northern forest) ecosystem full of animals like moose, wolves, rabbits and weasels. Even though it is up on a hillside, there were many sucker fish bones found at the site. We think people were harvesting fish from the lake and bringing them to the site to eat and process for storage. The traditional knowledge of the Dane-zaa was essential to understanding why the bones were there and what their meaning was to the people that lived – and continue to live – in the community.

I think most people can be great scientists! Curiosity, drive and open mindedness have been my most helpful personality traits.

Tse’k’wa shows the ingenuity, intelligence and hard work of hundreds of generations of Ancestral Dane-zaa Peoples. When I visited the site with community members, including elder Garry Oker, they spoke about processing hides on-site. That knowledge is a connection across thousands of years. We had found evidence of pelt and hide processing in the animal bones that were thousands of years old and were continuous through the layers of soil at the site!

Meet Tamara

Tamara St. Pierre took part in the Tse’k’wa field school and is a member of Prophet River First Nation.

The Tse’k’wa field school was an amazing opportunity, and I’m grateful that I got to be part of it. I learned so much and obtained so many valuable skills, it was something I will never forget. When we met the archaeologists who had excavated the cave site, it blew my mind. It really goes to show how long our people had been living on the land and how sacred this site really is.

The course doesn’t only teach you how to properly excavate a site, but you also get to learn about the rich history of the First Nations People and the way they once lived off the land, and you get to meet the people who now dwell here. I feel proud that I got to be part of something that was so huge, and I didn’t even realise it at the time.

Tse’k’wa feels like home and everybody is so warm and welcoming. I love the way we all came together like a family and created lasting bonds with other students.

For me, the future feels like an unwoven tapestry. I go with the flow of nature and let the universe guide me where I am meant to be. I was working in the Lands Department for Prophet River at the time of participating in the field course, and I feel like I am meant to be a steward of the Land.

Meet the Tse’k’wa Heritage Society board

The board of Tse’k’wa Heritage Society (THS) is made up of representatives from three Dane-zaa First Nations: Doig River First Nation, Prophet River First Nation and West Moberly First Nations.

Garry Oker

Garry Oker is an elder of Doig River First Nation and President of the THS Board.

Doig River’s values and beliefs are expressed through our Dreamers’ (Nááchįį) songs. Nááchįį are Dane-zaa people who travel to heaven in their dreams and bring back songs which provide teachings, visions and prophecies from the creator. The Dreamers share these songs with our people to guide us through life on earth. These songs are remembered and performed by our Doig River Drummers.

It’s taken my whole lifetime to reclaim a lot of the land that was illegally taken from us. We were stripped of that land and those resources, and now we’re getting them back. Part of reclaiming these sacred places is to take up responsibility for maintaining them. It’s the Indigenous Peoples’ job to make sure that there are opportunities for future generations to connect with the stories and artefacts. The understanding of who we are as Beaver People has been almost wiped out. In schools, they didn’t talk about local Beaver history until recently; we pushed, and now there’s demand for it. For us to reclaim these places, it’s important that our narrative and our perspective of the story is what we pass onto the next generation.

Our aim for the future is to go digital. We want to ensure that we have a presence in not only the physical world, but also the digital world. We are also connecting all these sacred places for Indigenous cultural tourism and we want to create a whole loop of interesting places to visit and see within our territory.

Valerie Askoty

Valerie Askoty is the current Chief of Prophet River First Nation.

Prophet River First Nation values honesty, hard work, compassion, empathy, friendship, love and kindness. Our traditions include drumming, tea dances, storytelling, language, hunting and camping, and these are still practiced by our people today.

Tse’k’wa is part of our indigenous roots. Many of our prophets descended from the area so it reminds us of where we came from.

We would like to work with our sister Beaver Nations to build this heritage site together. Tse’k’wa will be a space for sharing between our elders and members.

Education is a great tool to help you find out who you really are and where you came from.

Laura Webb

Laura Webb is an elder of West Moberly First Nations and Vice-President of THS.

West Moberly First Nations work with and develop alliances with other communities; we’re very mindful of sharing our territory. We express this by hosting feasts and get-togethers. Tse’k’wa is a place for our Peoples to get together and become strong and united, to become one again. Working together is the most important thing and learning how to share is another.

Tse’k’wa is important in this respect because it’s a place where we can be with the cave and listen to the stories of all the elders coming to the area.

At Tse’k’wa, we will continue the archaeological field schools, are important for training our people to do archaeological work and getting them the university credits that they need.

Non-indigenous students who are interested in archaeology need to experience our ways of learning and teaching. That’s why the Tse’k’wa field school is so important. Young archaeologists who are likely to be working with First Nation communities need to learn the protocols and make sure that they go about things in the right way and respect the land. They should find a guide in the community and learn from them.

Do you have a question for the Tse’k’wa Heritage Society, Jon or Alyssa?

Write it in the comments box below and they will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

0 Comments