Does local community action help our sense of global citizenship?

Dr Elsa Lee is a researcher at the University of Cambridge in the UK, who is studying the link between participation in waterway regeneration projects and the sense of global citizenship in young people

GLOSSARY

EQUITY – fair distribution of resources based on the needs of the recipients

GLOBAL CITIZEN – a person who is aware of the wider world and understands their place within it

UBUNTU – a southern African philosophy that we are shaped by our relationship with others

WATERWAY REGENERATION – restoring rivers, wetlands and water environments

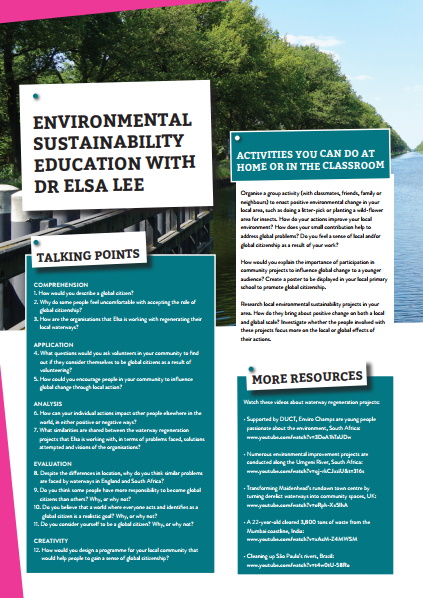

“By considering how our actions might affect people who live in a different country, we can support the health and well-being of people all around the world,” says Dr Elsa Lee, a researcher in environmental sustainability education at the University of Cambridge. Elsa is investigating various projects that are working with young people to improve local waterways in England and South Africa. She is interested in understanding if and how participation in these community projects can help young people to feel like global citizens.

WHAT IS GLOBAL CITIZENSHIP?

Global citizenship is an idea we are all part of one planet, so the way that we live in our communities and countries should also apply to the way we live as a member of a global community. We all have rights and responsibilities (such as the responsibility to care for others, and the right to be cared for when we are sick), and the goal of intergovernmental organisations like the United Nations is that everyone should have access to the same rights and share the same responsibilities. The concept of global citizenship is highlighted by UNESCO in their Sustainable Development Goals, and other terms with similar meanings include global awareness, world sensing and Ubuntu.

The idea is that if we consider ourselves as global citizens, we can begin to work towards equity for all. We should consider how our local actions might affect people who live elsewhere. For example, if we keep the water in our own rivers free of pollution, it will benefit people who live downstream, and even those on the other side of the world, when that clean water eventually reaches them.

“However, it’s very difficult to live this way,” explains Elsa. “It is a very big thing to ask people to keep the needs of everyone in the world in their mind when they make decisions about how to live their own lives.” We must also consider how people across the world have different levels of access to water, food and other resources, so these choices are more difficult to make for some than others. And we need to think about how different countries’ governing policies influence individual citizens’ capacities to be global citizens.

But, if we focus on doing small, positive things in our own communities, we can eventually make changes on a much bigger scale. While we do not all have the same access to material resources, we do already have the mental, emotional and spiritual attributes needed to live like this, we just need to believe that our small, considered acts make a difference, and know that we are always only a small part of a greater whole. “If we work together and care for ourselves and those nearest us, we can reach a point where we make decisions that are community-minded without really thinking about it” says Elsa. “And then all those community-minded decisions come together to have a positive impact at a global level.”

ELSA’S RESEARCH METHODS

Elsa’s research uses ethnographic methods, meaning she spends time alongside the volunteers and trainees who carry out waterway regeneration projects. “Before the pandemic, we visited these projects and walked alongside the rivers and water bodies where our participating organisations work, but restrictions prevented travel to field sites,” Elsa explains. Now, Elsa and her project researcher, Dr Mary Murphy, talk virtually to members of the organisations about the work they do, carrying out interviews online.

After transcribing these interviews into text, Elsa and Mary look for themes that are common and themes that are unique across different sets of interviews. This process is known as thematic content analysis and is a common way of analysing data that is collected in social science research. It allows researchers to see how different people agree or disagree about different topics. Elsa and Mary then consider factors such as economic, social, political and environmental conditions where the participants live and work. “Knowing the background conditions can make a big difference in how you interpret what your interviewees are telling you,” says Elsa. “It is also important to go back to your participants to ask them how they feel about your interpretations of what they are saying.”

Elsa aims to understand why different people who are doing the same things (waterway regeneration) but in different places (England and South Africa) come to the same or different conclusions about the impact of their work. “This is a very exciting stage of academic research projects, and it can go on for years!” she says.

LINKING WATERWAY REGENERATION TO GLOBAL CITIZENSHIP

Elsa’s data suggest that participation in community-based waterway regeneration projects influences young people’s local environmental citizenship. “Volunteering on projects like these gives young people an opportunity to respond to the problems that are highlighted every day in the media,” says Elsa. Young people are increasingly aware of the world’s problems, such as climate change and environmental degradation, but can be unsure of how to solve them. Initiatives such as waterway regeneration programmes provide an opportunity for young people to take action and address issues in their local community.

“While this has obvious benefits for the environment, it also has benefits for the young people themselves,” says Elsa. A sense of contributing to a solution has a positive impact on well-being, helping to overcome eco-anxiety, while volunteering also provides skills that can improve employment prospects and future economic well-being. These same impacts were reported by the young people in both England and South Africa.

However, Elsa has found that young people who are involved in community-based waterway regeneration projects do not necessarily identify as global citizens, and often feel uncomfortable with the idea. Some felt that the responsibility of global citizenship was too weighty, others felt that it was unattainable or unrealistic and some felt that it was inequitable. “If you live in circumstances where the challenges of meeting your responsibility to feed your family overwhelms your capacity to consider the impact of your actions on local waterways, let alone on global issues, then the notion of global citizenship heightens the sense of inequity,” explains Elsa. It is therefore very important to be mindful of how ideas like this might impact on different groups of people.

While global citizenship raised some critical issues for the young people Elsa worked with, the opportunities provided by waterway regeneration projects have allowed them to become active local citizens. If everyone around the globe had a sense of community spirit (in whatever form was most appropriate to their circumstances) and took local action to protect their environment, then the world would soon become a fairer and more sustainable place. “This is something which environmental activists and researchers have known for a long time,” says Elsa, “and it is very exciting to see how it works in the communities we studied.”

DR ELSA LEE

DR ELSA LEE

University of Cambridge, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Environmental Sustainability Education

RESEARCH PROJECT: Investigating how participation in local waterway regeneration projects influences a sense of global citizenship in young people: Connecting Water to Global Citizenship via Education for Sustainable Development

FUNDER: Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), UK: Grant number ES/S000151/1

PROJECT PARTNERS

FRIENDS OF THE LIESBEEK www.fol.org.za

The Liesbeek River in South Africa flows from its source on Table Mountain through Cape Town, providing a crucial water source for the city and acting as an ecological corridor through the urban environment. “The river is an important area for biodiversity,” says Sabelo. “Over 580 species have been recorded along the Liesbeek, many of which are endemic to the region.” However, the river suffers from problems of pollution and rubbish dumping. Urban drains lead directly into the river so anything on the roads will be washed into the Liesbeek when it rains, and residents often throw their waste into the river.

Friends of the Liesbeek work to conserve and rehabilitate the river and its surroundings. “Sometimes we have to organise a river clean-up twice a week due to the sheer volume of waste that accumulates,” says Phil. “We can remove 500 bin bags’ worth of rubbish every time.” They also remove invasive species, plant indigenous plants and are working to reinstate wetland environments by removing the walls from canalised sections of the river to allow natural flooding.

“People are disconnected from the river,” says Sabelo. Many buildings have their backs to the Liesbeek, and so residents are not engaged with their local environment. Friends of the Liesbeek are helping to promote sustainable urban conservation by organising community activities that allow people to connect to nature through engagement with the Liesbeek.

THAMES21 www.thames21.org.uk

Flowing through the heart of London, the River Thames is the second longest river in the UK. “London is a river city,” says Chris. “Its identity is permeated by the river. But today, the Thames is regarded as dirty and dangerous, and we want to change this attitude.”

Thames21 is working to tackle pollution in the river by organising regular clean-ups, providing all the equipment needed for volunteers to remove rubbish (they have over 1,000 pairs of wellies available!). They also encourage residents to participate in citizen science projects, such as conducting litter surveys. One of these projects found that 45% of plastic bottles found in the Thames are single-use water bottles. These findings were used to support the #Oneless campaign to install more public water fountains around London.

Thames21 also organises outdoor learning activities, using the river as an educational resource. These activities are not only for schools, but also for community members, with events such as nature walks and music or photography workshops held by the river. These activities encourage residents to engage with the Thames and to value the river environment.

“It is important to connect young people with issues of water management,” says Chris. “Young people are future decision-makers. They will be future water-consumers, waste-creators and environment-managers. If they understand the issues around waterways now, then they will make better decisions in the future.”

DUZI-UMNGENI CONSERVATION TRUST (DUCT) www.duct.org.za

The uMsunduzi and Umgeni Rivers in South Africa are severely damaged and polluted. As part of its mission to establish an ecologically healthy river system, DUCT works with young unemployed people who want to protect the environment, providing training and job opportunities in ecosystem restoration.

“I was unemployed when I finished school, so, for me, joining the project was first and foremost a job opportunity, not because I was particularly passionate about the environment,” says Portia. “But this quickly changed when I began to receive my training.”

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM238

EQUITY – fair distribution of resources based on the needs of the recipients

GLOBAL CITIZEN – a person who is aware of the wider world and understands their place within it

UBUNTU – a southern African philosophy that we are shaped by our relationship with others

WATERWAY REGENERATION – restoring rivers, wetlands and water environments

“By considering how our actions might affect people who live in a different country, we can support the health and well-being of people all around the world,” says Dr Elsa Lee, a researcher in environmental sustainability education at the University of Cambridge. Elsa is investigating various projects that are working with young people to improve local waterways in England and South Africa. She is interested in understanding if and how participation in these community projects can help young people to feel like global citizens.

WHAT IS GLOBAL CITIZENSHIP?

Global citizenship is an idea we are all part of one planet, so the way that we live in our communities and countries should also apply to the way we live as a member of a global community. We all have rights and responsibilities (such as the responsibility to care for others, and the right to be cared for when we are sick), and the goal of intergovernmental organisations like the United Nations is that everyone should have access to the same rights and share the same responsibilities. The concept of global citizenship is highlighted by UNESCO in their Sustainable Development Goals, and other terms with similar meanings include global awareness, world sensing and Ubuntu.

The idea is that if we consider ourselves as global citizens, we can begin to work towards equity for all. We should consider how our local actions might affect people who live elsewhere. For example, if we keep the water in our own rivers free of pollution, it will benefit people who live downstream, and even those on the other side of the world, when that clean water eventually reaches them.

“However, it’s very difficult to live this way,” explains Elsa. “It is a very big thing to ask people to keep the needs of everyone in the world in their mind when they make decisions about how to live their own lives.” We must also consider how people across the world have different levels of access to water, food and other resources, so these choices are more difficult to make for some than others. And we need to think about how different countries’ governing policies influence individual citizens’ capacities to be global citizens.

But, if we focus on doing small, positive things in our own communities, we can eventually make changes on a much bigger scale. While we do not all have the same access to material resources, we do already have the mental, emotional and spiritual attributes needed to live like this, we just need to believe that our small, considered acts make a difference, and know that we are always only a small part of a greater whole. “If we work together and care for ourselves and those nearest us, we can reach a point where we make decisions that are community-minded without really thinking about it” says Elsa. “And then all those community-minded decisions come together to have a positive impact at a global level.”

ELSA’S RESEARCH METHODS

Elsa’s research uses ethnographic methods, meaning she spends time alongside the volunteers and trainees who carry out waterway regeneration projects. “Before the pandemic, we visited these projects and walked alongside the rivers and water bodies where our participating organisations work, but restrictions prevented travel to field sites,” Elsa explains. Now, Elsa and her project researcher, Dr Mary Murphy, talk virtually to members of the organisations about the work they do, carrying out interviews online.

After transcribing these interviews into text, Elsa and Mary look for themes that are common and themes that are unique across different sets of interviews. This process is known as thematic content analysis and is a common way of analysing data that is collected in social science research. It allows researchers to see how different people agree or disagree about different topics. Elsa and Mary then consider factors such as economic, social, political and environmental conditions where the participants live and work. “Knowing the background conditions can make a big difference in how you interpret what your interviewees are telling you,” says Elsa. “It is also important to go back to your participants to ask them how they feel about your interpretations of what they are saying.”

Elsa aims to understand why different people who are doing the same things (waterway regeneration) but in different places (England and South Africa) come to the same or different conclusions about the impact of their work. “This is a very exciting stage of academic research projects, and it can go on for years!” she says.

LINKING WATERWAY REGENERATION TO GLOBAL CITIZENSHIP

Elsa’s data suggest that participation in community-based waterway regeneration projects influences young people’s local environmental citizenship. “Volunteering on projects like these gives young people an opportunity to respond to the problems that are highlighted every day in the media,” says Elsa. Young people are increasingly aware of the world’s problems, such as climate change and environmental degradation, but can be unsure of how to solve them. Initiatives such as waterway regeneration programmes provide an opportunity for young people to take action and address issues in their local community.

“While this has obvious benefits for the environment, it also has benefits for the young people themselves,” says Elsa. A sense of contributing to a solution has a positive impact on well-being, helping to overcome eco-anxiety, while volunteering also provides skills that can improve employment prospects and future economic well-being. These same impacts were reported by the young people in both England and South Africa.

However, Elsa has found that young people who are involved in community-based waterway regeneration projects do not necessarily identify as global citizens, and often feel uncomfortable with the idea. Some felt that the responsibility of global citizenship was too weighty, others felt that it was unattainable or unrealistic and some felt that it was inequitable. “If you live in circumstances where the challenges of meeting your responsibility to feed your family overwhelms your capacity to consider the impact of your actions on local waterways, let alone on global issues, then the notion of global citizenship heightens the sense of inequity,” explains Elsa. It is therefore very important to be mindful of how ideas like this might impact on different groups of people.

While global citizenship raised some critical issues for the young people Elsa worked with, the opportunities provided by waterway regeneration projects have allowed them to become active local citizens. If everyone around the globe had a sense of community spirit (in whatever form was most appropriate to their circumstances) and took local action to protect their environment, then the world would soon become a fairer and more sustainable place. “This is something which environmental activists and researchers have known for a long time,” says Elsa, “and it is very exciting to see how it works in the communities we studied.”

DR ELSA LEE

DR ELSA LEE

University of Cambridge, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Environmental Sustainability Education

RESEARCH PROJECT: Investigating how participation in local waterway regeneration projects influences a sense of global citizenship in young people: Connecting Water to Global Citizenship via Education for Sustainable Development

FUNDER: Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), UK: Grant number ES/S000151/1

FRIENDS OF THE LIESBEEK www.fol.org.za

The Liesbeek River in South Africa flows from its source on Table Mountain through Cape Town, providing a crucial water source for the city and acting as an ecological corridor through the urban environment. “The river is an important area for biodiversity,” says Sabelo. “Over 580 species have been recorded along the Liesbeek, many of which are endemic to the region.” However, the river suffers from problems of pollution and rubbish dumping. Urban drains lead directly into the river so anything on the roads will be washed into the Liesbeek when it rains, and residents often throw their waste into the river.

Friends of the Liesbeek work to conserve and rehabilitate the river and its surroundings. “Sometimes we have to organise a river clean-up twice a week due to the sheer volume of waste that accumulates,” says Phil. “We can remove 500 bin bags’ worth of rubbish every time.” They also remove invasive species, plant indigenous plants and are working to reinstate wetland environments by removing the walls from canalised sections of the river to allow natural flooding.

“People are disconnected from the river,” says Sabelo. Many buildings have their backs to the Liesbeek, and so residents are not engaged with their local environment. Friends of the Liesbeek are helping to promote sustainable urban conservation by organising community activities that allow people to connect to nature through engagement with the Liesbeek.

THAMES21 www.thames21.org.uk

Flowing through the heart of London, the River Thames is the second longest river in the UK. “London is a river city,” says Chris. “Its identity is permeated by the river. But today, the Thames is regarded as dirty and dangerous, and we want to change this attitude.”

Thames21 is working to tackle pollution in the river by organising regular clean-ups, providing all the equipment needed for volunteers to remove rubbish (they have over 1,000 pairs of wellies available!). They also encourage residents to participate in citizen science projects, such as conducting litter surveys. One of these projects found that 45% of plastic bottles found in the Thames are single-use water bottles. These findings were used to support the #Oneless campaign to install more public water fountains around London.

Thames21 also organises outdoor learning activities, using the river as an educational resource. These activities are not only for schools, but also for community members, with events such as nature walks and music or photography workshops held by the river. These activities encourage residents to engage with the Thames and to value the river environment.

“It is important to connect young people with issues of water management,” says Chris. “Young people are future decision-makers. They will be future water-consumers, waste-creators and environment-managers. If they understand the issues around waterways now, then they will make better decisions in the future.”

DUZI-UMNGENI CONSERVATION TRUST (DUCT) www.duct.org.za

The uMsunduzi and Umgeni Rivers in South Africa are severely damaged and polluted. As part of its mission to establish an ecologically healthy river system, DUCT works with young unemployed people who want to protect the environment, providing training and job opportunities in ecosystem restoration.

“I was unemployed when I finished school, so, for me, joining the project was first and foremost a job opportunity, not because I was particularly passionate about the environment,” says Portia. “But this quickly changed when I began to receive my training.”

This training involved identification of indigenous and alien species during invasive vegetation clearances, inspections of waste management sites and using Google Earth to map out areas of different habitats. “We also receive individual training to help us with our vocational pathway, and I chose to get involved with waste management and recycling,” she says.

With the help of DUCT, Portia founded her own recycling company where she collects waste from local schools, then separates out recyclable materials which she sells to make money.

In many residential areas there is no municipal waste collection service, so people dispose of their waste by dumping it in the river or wetland areas. Members of DUCT clear up this rubbish, and after receiving training in permaculture, they have been planting community gardens in areas that were once used as rubbish dumps. “These small actions motivate communities to be custodians of their own environment,” says Pandora. “By working in a small area where practical impact can be observed, people believe that they can fix the problems and make a difference.”

Read about some of the other waterway regeneration projects Elsa is working with:

- LIBERTY NPO libertynpo.co.za

- NATURE CONNECT (formerly Cape Town Environmental Education Trust) natureconnect.earth

- THE SEVERN RIVERS TRUST severnriverstrust.com and www.unlockingthesevern.co.uk

As part of UNESCO’s Sustainable Development Goals, all learners should be empowered with the knowledge, skills and values necessary to shape a sustainable future. Researchers studying environmental sustainability education want to understand how this can be achieved by placing sustainability at the heart of learning.

Environmental sustainability education unbalances the three pillars of sustainable development (i.e. economy, environment and society, or profit, planet and people). “We put the emphasis on the environment, arguing that the environment is foundational, and then think about what emphasising the sustainability of the environment means for education,” Elsa explains.

Elsa’s research sets out to balance the needs of humans with the needs of other living and non-living components of Earth. “For me, the capacity to respond in some small way to understanding the challenges of human-generated environmental degradation is crucial, and fundamental to my way of life,” she says. “I cannot choose to live any other way.”

EXPLORE A CAREER IN ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY EDUCATION

“The very best way to get started on this career path is to find a local organisation and start volunteering,” suggests Elsa. This could be with a local waterway regeneration project, a wildlife trust or local conservancy group. “Working with your local community will start you on your environmental education journey, and you can choose where to go from there.”

Elsa also recommends citizen science projects as an opportunity to address large-scale issues through local action. The following organisations have many projects available:

• The Natural History Museum www.nhm.ac.uk/take-part/citizen-science.html

• EU Citizen Science www.eu-citizen.science

• National Geographic www.nationalgeographic.org/idea/citizen-science-projects

• The Nature Conservancy www.nature.org/en-us

Elsa suggests that geography, the arts, economics, ecology and business are important subjects to study. But as a transdisciplinary issue, all subjects will be useful for addressing the challenges in the field of environmental sustainability education. It is really about what different disciplines of study can bring to support the search for solutions.

Write it in the comments box below and Elsa will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

Dear Dr Elsa,

I checked your profile and was really fascinated about your achievements so far both in the academic setting and how you impact the lives of youth.

I am a Chemical Engineering graduate with a Masters degree in Business Administration from University of Wales. I have also worked as a Project Assistant, Liaison Officer, Content Writer and Science Teacher.

I had a career break due to child raising but for the past 3 years I have been wanting to carve a niche for myself in the area of Sustainability, Energy and Climate. I’ve actually done professional courses like SEA and LEED green associate and been volunteering with organizations into this areas.

I want to further my studies to doctorate level and would like to discuss that with you if you could grant me a chance to speak with you regarding this. I have been thinking about sustainability, energy policy, sustainable development and diplomacy etc. Kindly, get in touch with me when you see this… I just need some guidance and most especially how to study at Homerton College! Warm regards.

Dr Lee has been notified and will connect directly via email.