Understanding language communities: the multilingual, the transnational and the translingual

Professor Stephen Hutchings, based at the University of Manchester in the UK, has been leading a modern languages research programme exploring the relationship between language and community

The internet, international business and travel, migration, climate issues… in many ways, our world is getting ‘smaller’.

Globalisation facilitates interactions that are no longer restricted by borders or distance and brings people from different backgrounds together. So, how does language operate within this modern era? To what extent are communities defined by language? Does the transcendence of boundaries affect our sense of belonging? How does each language preserve its integrity at the same time as opening communities to the wider world?

It is with these fascinating questions in mind that, in 2016, Professor Stephen Hutchings embarked on a research programme called Cross-Language Dynamics: Reshaping Community. While Stephen is based at the University of Manchester, this highly collaborative programme, due to end in 2021, is composed of three research strands, each led by colleagues at different core institutions: Professor Yaron Matras of the University of Manchester (multilingual), Professors Andy Byford and Anoush Ehteshami at Durham University (transnational), and Professor Catherine Davies at the School of Advanced Study, University of London (translingual).

Digital technologies and unprecedented global population movements have transformed the relationships between individuals and the communities they belong to (national, local, religious and other), between those communities, and between communities and nations. It is impossible to understand the processes involved in these shifts and changes without studying language’s central role in creating and transcending the boundaries that define communities.

THE THREE STRANDS

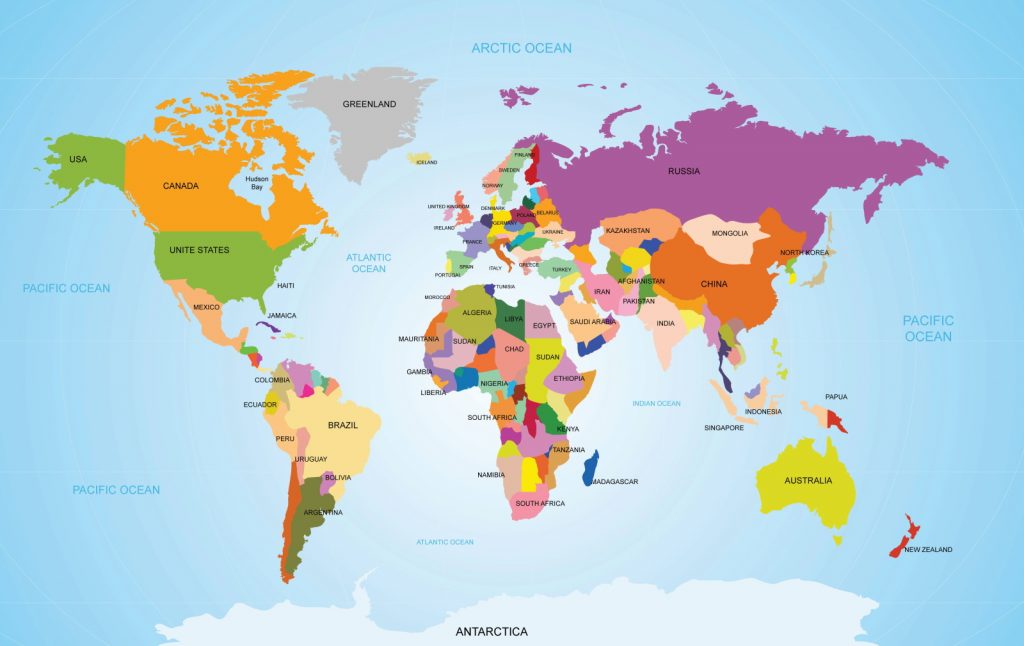

The project strands reflect what the team sees as the main ways that language helps configure communities. “Many of our large, global cities are characterised by increased linguistic diversity and this was the focus of our multilingual strand,” explains Stephen. “The technological advances that are driving the most recent phase of globalisation have also reinforced the ability of speakers of single languages to communicate across national boundaries, strengthening ties across the Russian-speaking, Spanish-speaking and Arabic-speaking worlds, for example. These communities were studied within our transnational strand.”

Finally, the translingual strand is related to how enhanced global connectivity is fostering the creation and maintenance of communities defined by their ability to cross boundaries between languages, whether through a shared appreciation of non-linguistic art forms like music, or as the result of a tendency to mix languages in everyday communication, or via the skills and commitment of translators.

COLLABORATION

The team has collaborated with stakeholders that share interest in communities within the UK, other nations, and across national and linguistic boundaries. These include foreign policy makers, arts organisations, local authorities, schools and community groups. “Collaboration has involved helping stakeholders solve problems important to them, while we have benefited from policymaker expertise in our research,” says Stephen. “We have worked together with our partners on joint initiatives that include a city-wide celebration of linguistic diversity in Manchester and a play that explores the experiences of cancer sufferers across the Arabic-speaking world. Without these collaborations, we could not have realised our research goals or demonstrated the value of languages.”

HIGHLIGHTS

One of the things that Stephen is most proud of is the central role that young early-career researchers have played. “Their involvement bodes well for the future of our profession and confirms that modern languages is benefiting from the injection of new creativity and dynamism,” he explains.

LONG-TERM

The Cross-Language Dynamics: Reshaping Community programme has achieved a number of legacies. “First, we have succeeded in raising the profile of modern languages within and beyond Higher Education. Our contributions to addressing key societal issues – including those associated with societal cohesion, health, conflict and cultural diplomacy – have helped re-establish modern languages as one of the foremost humanities disciplines,” says Stephen. “Secondly, the partnerships we have forged with stakeholders have changed attitudes to the value of the discipline to policy makers. Thirdly, we have changed the public narrative around the discipline, helping to break down the false ‘community/modern’ languages distinction, demonstrating the importance of linguistic diversity, promoting the extent of multilingual talent and creativity within and beyond the UK, and confronting negative perceptions of a subject ‘in decline’.”

PROFESSOR STEPHEN HUTCHINGS

PROFESSOR STEPHEN HUTCHINGS

Russian Studies, School of Arts, Languages and Culture, The University of Manchester, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Modern Languages

RESEARCH PROJECT: ‘Cross-Language Dynamics: Reshaping Community’: investigating the relationship between language and community for the benefit of a more open world

FUNDER: Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC)

THE POWER OF MODERN LANGUAGES

Stephen explains what modern languages mean to him.

There is a tendency to view modern languages as providing little more than practical knowledge for use in business and diplomacy. This, of course, is important, but the subject is so much more than a useful skill. It is worth studying for the unique insights it offers into other cultures, mindsets and value systems. Knowledge of multiple languages is a source of huge creativity and talent within the arts. It fosters wellbeing within individuals, and within and across entire communities. Modern languages provides a distinctive perspective on international conflict, cross-community cohesion and intercultural understanding. We should stop seeing the subject as an exotic and peripheral ‘add on’ to the core curriculum, and recognise that, with its focus on communication and what it means to be ‘different’, it represents the essence of humanities.

Rather than extending the dominance of English, the impact of globalisation on international trade is highlighting the advantage to businesses of ‘selling in the language of the client’. However, the range of career options open to modern linguists is much broader than those on offer in the world of commerce, or translation, important though these are. With ever-increasing migration movements, management of diversity – for example – is becoming critical to national and local policymaking within individual countries. And as the clearly defined ideological blocs of the Cold War fade away, countries are turning to softer, more subtle approaches to promoting their values and interests. Without the relevant linguistic and cultural knowledge, such approaches cannot succeed. There is a growing appreciation of the benefits of multilingualism to public health and creativity in the arts. All these areas are generating opportunities to young people with an interest in languages. Finally, for those young people who choose to study a language at university, the year they spend abroad practising and honing their linguistic skills becomes the defining year of their lives. This was certainly my experience!

I am a child of the Cold War. During my school years, anxiety over nuclear conflict with the Soviet Union and the communist world was central to my experience. Even at that early stage, it struck me that fear on both sides was exacerbated by a lack of understanding of how ordinary people felt and thought. I recognised that it is only through taking the trouble to learn the language of the other that such understanding can be properly attained. It was this that motivated me to learn Russian.

Some of my most memorable experiences come from periods I spent in the Soviet Union and in post-Soviet Russia in connection with my studies. I will never forget long, intense conversations into the small hours of the morning around the kitchen tables of those ordinary Soviet families who had welcomed me into their homes at the height of the Cold War. It was here that I learned to appreciate the true meaning of what it is to communicate and the value of understanding what makes us similar to, and different from, one another.

WHAT IS A HERITAGE LANGUAGE?

According to Ann Kelleher, University of California, Davis, “The term ‘heritage language’ is used to identify languages other than the dominant language (or languages) in a given social context. In the United States, English is the de facto dominant language (not an “official” language, but the primary language used in government, education, and public communication); thus, any language other than English can be considered a ‘heritage language’ for speakers of that language.”

THE MULTILINGUAL

DR LEONIE GAISER

ROLE ON THE PROJECT: PHD STUDENT AND RESEARCH ASSISTANT

CURRENT ROLE: LECTURER IN LINGUISTICS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER, UK

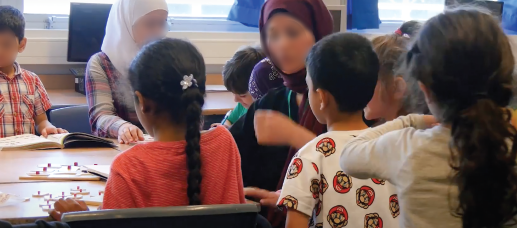

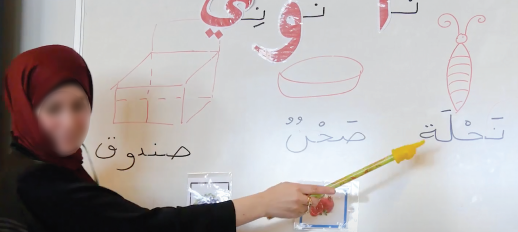

Our research explores how speakers of ‘heritage’ languages maintain their languages and dialects in the linguistically diverse city of Manchester, and how language can help create a sense of community in the diaspora setting. One of our research interests is to learn more about the work of language supplementary schools, which teach heritage languages to children on the weekend. We have set up a support platform for supplementary schools to offer a range of activities for pupils and teachers.

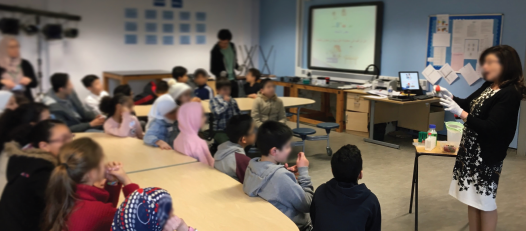

We have worked together with the Manchester Institute of Biotechnology and a range of multilingual scientists from across the University of Manchester to deliver interactive sessions in the languages taught at the schools. Our enrichment sessions have included enzyme experiments and strawberry DNA extraction, led by multilingual scientists. Experiments are followed by hands-on activities for students, for example making ‘DNA bracelets’ to take home. The day ends with (typically multilingual) question and answer sessions about the scientists’ work.

Our sessions give children opportunities to experience their heritage language in the context of scientific experiments or museum exhibitions, and in interaction with university staff. The sessions expand pupils’ vocabulary in the heritage language and allow them to link their language skills with science and museum exhibits. Meeting university researchers who speak their language enhances students’ confidence in their language skills and their complex, multi-layered identities.

My doctoral research has shown how experiences of ‘community’ are both imagined and practiced. People’s mutual identification with languages and their efforts to maintain languages serve to create and strengthen a sense of belonging and identification with the multilingual setting, as well as a way to inter-connect with family and friends.

Our research has offered insights into the various ways in which language users maintain their languages and acquire new ones. Supplementary schools vary widely in size, curricula, staff qualifications and training, the type of premises used, and their teaching and learning approaches. My doctoral research has shown that, contrary to what is often discussed in public discourse, maintaining heritage languages is anything but self-segregating. These languages are relevant in the present-day UK context and for its global future, and supplementary schools help children turn their heritage into valuable skills.

DR MARÍA SOLEDAD MONTAÑEZ

ROLE ON THE PROJECT: RESEARCH FELLOW, COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT IN THE LATIN AMERICAN COMMUNITY IN LONDON

CURRENT ROLE: VISITING FELLOW, THE INSTITUTE OF MODERN LANGUAGES RESEARCH, SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON/LECTURER IN SPANISH, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW, UK

I worked with Southwark Council to explore new tools, resources and opportunities for collaboration and engagement between the Latin American groups in Southwark and the wider community. I co-designed and co-delivered Cartonera workshops for young Latin Americans. Cartoneras (also known as cardboard publishers) is a unique grassroots Latin American publishing phenomenon, which offers alternative forms of community engagement, activism and social change. The Cartoneras grassroots initiative in Latin America catalyses civic participation and activism within vulnerable and marginalised communities.

The Cartoneras Creative Engagement Project was a multi-party collaboration involving two AHRC projects – ‘Cross Language Dynamics: Reshaping Community’ and ‘Cartonera Publishing: Relations, Meaning and Community in Movement’, the British Library, a group consisting of the Indoamerican Refugee and Migrant Organisation (IRMO), Southwark Council and the Migration Museum.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM262

Globalisation facilitates interactions that are no longer restricted by borders or distance and brings people from different backgrounds together. So, how does language operate within this modern era? To what extent are communities defined by language? Does the transcendence of boundaries affect our sense of belonging? How does each language preserve its integrity at the same time as opening communities to the wider world?

It is with these fascinating questions in mind that, in 2016, Professor Stephen Hutchings embarked on a research programme called Cross-Language Dynamics: Reshaping Community. While Stephen is based at the University of Manchester, this highly collaborative programme, due to end in 2021, is composed of three research strands, each led by colleagues at different core institutions: Professor Yaron Matras of the University of Manchester (multilingual), Professors Andy Byford and Anoush Ehteshami at Durham University (transnational), and Professor Catherine Davies at the School of Advanced Study, University of London (translingual).

Digital technologies and unprecedented global population movements have transformed the relationships between individuals and the communities they belong to (national, local, religious and other), between those communities, and between communities and nations. It is impossible to understand the processes involved in these shifts and changes without studying language’s central role in creating and transcending the boundaries that define communities.

THE THREE STRANDS

The project strands reflect what the team sees as the main ways that language helps configure communities. “Many of our large, global cities are characterised by increased linguistic diversity and this was the focus of our multilingual strand,” explains Stephen. “The technological advances that are driving the most recent phase of globalisation have also reinforced the ability of speakers of single languages to communicate across national boundaries, strengthening ties across the Russian-speaking, Spanish-speaking and Arabic-speaking worlds, for example. These communities were studied within our transnational strand.”

Finally, the translingual strand is related to how enhanced global connectivity is fostering the creation and maintenance of communities defined by their ability to cross boundaries between languages, whether through a shared appreciation of non-linguistic art forms like music, or as the result of a tendency to mix languages in everyday communication, or via the skills and commitment of translators.

COLLABORATION

The team has collaborated with stakeholders that share interest in communities within the UK, other nations, and across national and linguistic boundaries. These include foreign policy makers, arts organisations, local authorities, schools and community groups. “Collaboration has involved helping stakeholders solve problems important to them, while we have benefited from policymaker expertise in our research,” says Stephen. “We have worked together with our partners on joint initiatives that include a city-wide celebration of linguistic diversity in Manchester and a play that explores the experiences of cancer sufferers across the Arabic-speaking world. Without these collaborations, we could not have realised our research goals or demonstrated the value of languages.”

HIGHLIGHTS

One of the things that Stephen is most proud of is the central role that young early-career researchers have played. “Their involvement bodes well for the future of our profession and confirms that modern languages is benefiting from the injection of new creativity and dynamism,” he explains.

LONG-TERM

The Cross-Language Dynamics: Reshaping Community programme has achieved a number of legacies. “First, we have succeeded in raising the profile of modern languages within and beyond Higher Education. Our contributions to addressing key societal issues – including those associated with societal cohesion, health, conflict and cultural diplomacy – have helped re-establish modern languages as one of the foremost humanities disciplines,” says Stephen. “Secondly, the partnerships we have forged with stakeholders have changed attitudes to the value of the discipline to policy makers. Thirdly, we have changed the public narrative around the discipline, helping to break down the false ‘community/modern’ languages distinction, demonstrating the importance of linguistic diversity, promoting the extent of multilingual talent and creativity within and beyond the UK, and confronting negative perceptions of a subject ‘in decline’.”

PROFESSOR STEPHEN HUTCHINGS

PROFESSOR STEPHEN HUTCHINGS

Russian Studies, School of Arts, Languages and Culture, The University of Manchester, UK

FIELD OF RESEARCH: Modern Languages

RESEARCH PROJECT: ‘Cross-Language Dynamics: Reshaping Community’: investigating the relationship between language and community for the benefit of a more open world

FUNDER: Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC)

Stephen explains what modern languages mean to him.

There is a tendency to view modern languages as providing little more than practical knowledge for use in business and diplomacy. This, of course, is important, but the subject is so much more than a useful skill. It is worth studying for the unique insights it offers into other cultures, mindsets and value systems. Knowledge of multiple languages is a source of huge creativity and talent within the arts. It fosters wellbeing within individuals, and within and across entire communities. Modern languages provides a distinctive perspective on international conflict, cross-community cohesion and intercultural understanding. We should stop seeing the subject as an exotic and peripheral ‘add on’ to the core curriculum, and recognise that, with its focus on communication and what it means to be ‘different’, it represents the essence of humanities.

Rather than extending the dominance of English, the impact of globalisation on international trade is highlighting the advantage to businesses of ‘selling in the language of the client’. However, the range of career options open to modern linguists is much broader than those on offer in the world of commerce, or translation, important though these are. With ever-increasing migration movements, management of diversity – for example – is becoming critical to national and local policymaking within individual countries. And as the clearly defined ideological blocs of the Cold War fade away, countries are turning to softer, more subtle approaches to promoting their values and interests. Without the relevant linguistic and cultural knowledge, such approaches cannot succeed. There is a growing appreciation of the benefits of multilingualism to public health and creativity in the arts. All these areas are generating opportunities to young people with an interest in languages. Finally, for those young people who choose to study a language at university, the year they spend abroad practising and honing their linguistic skills becomes the defining year of their lives. This was certainly my experience!

I am a child of the Cold War. During my school years, anxiety over nuclear conflict with the Soviet Union and the communist world was central to my experience. Even at that early stage, it struck me that fear on both sides was exacerbated by a lack of understanding of how ordinary people felt and thought. I recognised that it is only through taking the trouble to learn the language of the other that such understanding can be properly attained. It was this that motivated me to learn Russian.

Some of my most memorable experiences come from periods I spent in the Soviet Union and in post-Soviet Russia in connection with my studies. I will never forget long, intense conversations into the small hours of the morning around the kitchen tables of those ordinary Soviet families who had welcomed me into their homes at the height of the Cold War. It was here that I learned to appreciate the true meaning of what it is to communicate and the value of understanding what makes us similar to, and different from, one another.

WHAT IS A HERITAGE LANGUAGE?

According to Ann Kelleher, University of California, Davis, “The term ‘heritage language’ is used to identify languages other than the dominant language (or languages) in a given social context. In the United States, English is the de facto dominant

language (not an “official” language, but the primary language used in government, education, and public communication); thus, any language other than English can be considered a ‘heritage language’ for speakers of that language.”

THE MULTILINGUAL

DR LEONIE GAISER

ROLE ON THE PROJECT: PHD STUDENT AND RESEARCH ASSISTANT

CURRENT ROLE: LECTURER IN LINGUISTICS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER, UK

Our research explores how speakers of ‘heritage’ languages maintain their languages and dialects in the linguistically diverse city of Manchester, and how language can help create a sense of community in the diaspora setting. One of our research interests is to learn more about the work of language supplementary schools, which teach heritage languages to children on the weekend. We have set up a support platform for supplementary schools to offer a range of activities for pupils and teachers.

We have worked together with the Manchester Institute of Biotechnology and a range of multilingual scientists from across the University of Manchester to deliver interactive sessions in the languages taught at the schools. Our enrichment sessions have included enzyme experiments and strawberry DNA extraction, led by multilingual scientists. Experiments are followed by hands-on activities for students, for example making ‘DNA bracelets’ to take home. The day ends with (typically multilingual) question and answer sessions about the scientists’ work.

Our sessions give children opportunities to experience their heritage language in the context of scientific experiments or museum exhibitions, and in interaction with university staff. The sessions expand pupils’ vocabulary in the heritage language and allow them to link their language skills with science and museum exhibits. Meeting university researchers who speak their language enhances students’ confidence in their language skills and their complex, multi-layered identities.

My doctoral research has shown how experiences of ‘community’ are both imagined and practiced. People’s mutual identification with languages and their efforts to maintain languages serve to create and strengthen a sense of belonging and identification with the multilingual setting, as well as a way to inter-connect with family and friends.

Our research has offered insights into the various ways in which language users maintain their languages and acquire new ones. Supplementary schools vary widely in size, curricula, staff qualifications and training, the type of premises used, and their teaching and learning approaches. My doctoral research has shown that, contrary to what is often discussed in public discourse, maintaining heritage languages is anything but self-segregating. These languages are relevant in the present-day UK context and for its global future, and supplementary schools help children turn their heritage into valuable skills.

DR MARÍA SOLEDAD MONTAÑEZ

ROLE ON THE PROJECT: RESEARCH FELLOW, COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT IN THE LATIN AMERICAN COMMUNITY IN LONDON

CURRENT ROLE: VISITING FELLOW, THE INSTITUTE OF MODERN LANGUAGES RESEARCH, SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON/LECTURER IN SPANISH, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW, UK

I worked with Southwark Council to explore new tools, resources and opportunities for collaboration and engagement between the Latin American groups in Southwark and the wider community. I co-designed and co-delivered Cartonera workshops for young Latin Americans. Cartoneras (also known as cardboard publishers) is a unique grassroots Latin American publishing phenomenon, which offers alternative forms of community engagement, activism and social change. The Cartoneras grassroots initiative in Latin America catalyses civic participation and activism within vulnerable and marginalised communities.

The Cartoneras Creative Engagement Project was a multi-party collaboration involving two AHRC projects – ‘Cross Language Dynamics: Reshaping Community’ and ‘Cartonera Publishing: Relations, Meaning and Community in Movement’, the British Library, a group consisting of the Indoamerican Refugee and Migrant Organisation (IRMO), Southwark Council and the Migration Museum.

This project explored notions of community, identity and language through a series of workshops, from creative writing to book making with young Latin Americans. The idea was to publish the voices of young Latin Americans in London as the UK was preparing to exit the EU.

Creativity plays a vital role in community engagement in cross-cultural contexts. Creativity should be understood as a source of free expression, adaptability and innovation, and an alternative to more bureaucratic forms of consultations. Creative practice offers the opportunity to (re)connect with diverse communities through multiple media and languages, allowing alternative methods of communication understanding.

The Cartoneras workshops allowed the young people to develop a better sense of identity and belonging, as the motto chosen by them was ‘to work as a team’.

The Latin American community is diverse – ethnically, linguistically, culturally, and geographically distinctive from each other – Latin American is far from a homogenous concept. Language barriers play a role in preventing many Latin Americans from accessing key services.

My research is community-focused, so a typical day would involve lots of talking with different stakeholders, from formal and semi-structured interviews to meetings, and delivering community projects myself. Working on community engagement means that most of the research is done ‘on the ground’.

THE TRANSNATIONAL

DR JULINE BEAUJOUAN

ROLE ON THE PROJECT: PHD STUDENT INVESTIGATING THE ISLAMIC STATE’S DISCURSIVE POWER IN THE MENA REGION

CURRENT ROLE: POST-DOCTORAL RESEARCH FELLOW, PEACE AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION EVIDENCE PLATFORM (PCREP), UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH, UK

My research looks at how the Islamic State’s (IS) message gained significant traction in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. It also looks at if/how it shaped the way local populations understand conflict dynamics in the region.

IS used language to break the geographical and concrete borders between Iraq and Syria, but also the invisible and imagined borders between nations, regions, religions and cultures. Language was used as a tool to deconstruct as many competing identities, to allow each individual to enter the global and communal culture promoted by the group.

By self-declaring itself a new ‘state’ actor, IS entered in direct competition for power and legitimacy over territories and populations with the existing MENA states. This prompted military offensives against IS in Iraq and Syria. Despite the common threat, the war against IS created additional layers of inter-state frictions in the MENA and shed light on the failure of regional bodies to take collective measures.

While reclaiming their Islamic heritage and identity, the populations I interviewed in Jordan and Tunisia rejected IS’ methods and the strict application of Shari’ah law. Rather, they favoured a more humanistic Islam that recognises diversity and endorses living together. As such, IS failed to transform the very nature of Islam and Muslim communities.

One of the best parts of this project was that there was no such thing as a ‘typical day’. While I spent hours collecting and coding IS’ material during the first months of the project, I also spent several months in the MENA region where I conducted interviews and co-organised and participated in international events.

During this research, I became aware of the value of academic endeavours. They function as relational matters that can endorse a form of more sustainable, humanistic, universal way to carry out informed research that promotes connections between spaces and individuals to open dialogue and debate among a multitude of voices.

I co-authored a book with my colleagues Professor Ehteshami and Dr Rasheed that collects the key findings of our research. I also edited and contributed to another volume that brought together local voices from the Middle East on a key consequence of IS’ project, which is the Syrian refugee crisis. Finally, my first single-authored article recently got published by Studies in Conflict & Terrorism.

Communities are shaped by language. When it is used in a discourse, language becomes a powerful unifier that brings people together in the same community, and at the same time, a factor of exclusion.

For me, language is the key that opens the door to knowledge and, most importantly, understanding. My knowledge of several languages – French, English and Arabic – allowed me to widen my professional horizons by studying in the UK and researching the MENA region.

DR POLINA KLIUCHNIKOVA

ROLE ON THE PROJECT: POSTDOCTORAL RESEARCH ASSOCIATE, LANGUAGE BORDER: RUSSIAN IN FORMER SOVIET UNION MIGRATION

CURRENT ROLE: ASSOCIATE LECTURER IN RUSSIAN LANGUAGE AND CULTURE, THE UNIVERSITY OF ST ANDREWS, SCOTLAND, UK

My research project studied the changing role of the Russian language in the present-day migration to Russia from other post-Soviet countries. What do the language requirements introduced by the Russian state look like and how does the language testing procedure shape the lives of people who want to receive a work permit or apply for a leave to remain? What are the social and cultural effects of using a ‘non-standard’ variety of the language? How do local communities see and perform their role in helping migrants to adjust to the new context in terms of language use?

Citizens of most of former Soviet Union (FSU) countries enter Russia visa-free. But for employment of any duration, most migrants require a work permit which, in most cases, includes a language test. The test has three parts – language tasks (including reading, grammar, listening, speaking, and writing), as well as questions on Russian history and legislation – and is now valid for three years.

The main discussion about the tests is not about their necessity, but the content of them. While the language tasks are rather simple, they require knowledge of formal grammar rules that lots of current migrants don’t have. The other two components of the test, Russian history and especially law, are also presented in a complicated, advanced language.

Many people who come to Russia are multilingual. However, FSU migrants find themselves in a different environment where the Russian language is given priority in most communication. A slight accent or non-standard grammar do not go unnoticed. The effect may take many forms – from casual comments to limited job options or restricted access to basic welfare.

The life of migrants in Russia is not easy and language issues do not come first in the list of daily challenges. But the significance of at least threshold language competence has started to come to the foreground – people have become more aware of it while looking for accommodation, registering at a clinic, or enrolling their children at a local school. This is where support networks are vital; migrant communities have developed ways to adapt to their new reality.

For many people who come to another country, ‘community’ usually stands for a group of their compatriots – people with a similar trajectory who speak the same language. In this project, we also worked with another type of community – that emerging around providing language support and promoting multilingualism. For example, an afterschool course for migrant children, which creates a network of parents and volunteering teachers in the area, or a language class for female migrants, which also provides them with a safe social space to discuss their experiences.

I was lucky to do most of my fieldwork in 2017, when the importance of language provision for migrants was realised in Russia. I witnessed the emergence of a country-wide network of educators and activists working with migrant children and adults. Another interesting and unexpected angle was to explore the Russian language provision practices in other post-Soviet countries (Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan). We are now at the very final stage of the project, editing articles for publication.

THE TRANSLINGUAL

DR NAOMI WELLS

ROLE ON PROJECT: POSTDOCTORAL RESEARCH ASSOCIATE, DIGITAL HUMANITIES AND TRANSLINGUAL COMMUNITIES

CURRENT ROLE: LECTURER IN ITALIAN AND SPANISH WITH DIGITAL HUMANITIES/CO-DIRECTOR OF THE DOCTORAL CENTRE INSTITUTE OF MODERN LANGUAGES RESEARCH/DIGITAL HUMANITIES RESEARCH HUB, SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON, UK

My research aims to help us better understand how multilingual individuals and groups use the internet and social media to communicate and represent their identities and interests. While people have always moved across languages in their daily lives, the internet provides new ways for people to use and mix languages, and to communicate and share media content with speakers of different languages around the world.

As the pandemic has highlighted, it is important to recognise the ways the internet and social media can help us to stay connected. They also strengthen our feelings of belonging to our close community of family and friends, as well as new communities we can form online. Focusing on language, online communication may allow people who have migrated to a new country to stay connected and continue using their languages in ways that can help prevent feelings of isolation.

Latin American communities’ digital presence has increased the visibility of the community in the UK. While Latin Americans have been one of the fastest growing communities in London in the past decade, their interests and concerns have often been politically and socially marginalised. Online communications can also help to build networks of people with shared interests and feelings of solidarity that can be particularly important for groups who are marginalised.

My research is revealing that the internet and social media provide new ways for people to express their sense of belonging to a community, but also greater possibilities to identify with and move across different communities. For example, someone might use a Spanish-language hashtag to show they belong to the Latin American community, but then switch to English for most of their communications. This is particularly true for young people who have grown up in the UK mainly using English with their friends online and offline, but for whom Spanish remains important for expressing their belonging to the Latin American community.

I enjoyed studying languages at school and experiences of travelling to different linguistic and cultural contexts. Studying languages at university, I realised I wanted to pursue research that would allow me to better understand the importance of languages in our daily lives and the cultural practices of different countries and communities.

One of the most valuable experiences has been the experience of studying, working and conducting research abroad. This was important not just for improving my language skills, but also for developing the ability to live and work across different languages and cultures, and for learning to be adaptable and open to the different perspectives and experiences that people may bring.

EXPLORE CAREERS IN MODERN LANGUAGES

• Stephen suggests you should engage with speakers of the language you’re interested in learning, as well as the cultures and societies you would like to learn more about. He recommends Target Jobs and the University of Manchester’s Language Careers page.

• Open Days references university and college open days across the UK, which are good opportunities to engage with staff and students and investigate future academic prospects.

• The Linguist List is a free resource that offers information about events and summer schools.

PATHWAY FROM SCHOOL TO MODERN LANGUAGES

“The pathway into a modern languages research career is, as for other subjects, usually via a PhD. Because, by its nature, the study of languages is closely interconnected with that of other disciplines, and because the relative status of different languages is changing all the time, my top tip would be to remain maximally flexible when identifying your PhD topic,” explains Stephen.

“Study more than one language and be prepared to acquire brand new ones; your existing linguistic experience and skills will serve you well. Take an interest in other humanities disciplines, depending on your own preferences and talents. The best PhDs (and the most successful research careers) are driven by sheer intellectual curiosity and passion. So, whilst following these tips, trust your own intuitions, instincts and interests.”

https://www.prospects.ac.uk/careers-advice/what-can-i-do-withmy-degree/modern-languages

THE TEAM’S TOP TIPS

01 – Learning a language is a long, hard slog. The novelty value one senses at the start of the journey wears off quite quickly and those long evenings spent learning obscure grammatical rules can seem pointless, especially when one is still struggling to hold a conversation in the language in question. The key is stamina, perseverance, and keeping your eye on the end goal.

02 – Don’t worry about not having an aptitude for language learning. Being good at languages comes with practice and time. Own your learning journey and be gentle with your mistakes. And most importantly, believe in yourself.

03 – Get involved in language-related projects or organisations as early as possible. Such opportunities will allow you to gain valuable experience and skills, and explore the richness and complexities of languages and ‘communities’ on your doorstep.

Do you have a question for Stephen, Leonie, María, Juline, Polina or Naomi?

Write it in the comments box below and Stephen, Leonie, María, Juline, Polina or Naomi will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)